It had been six years since I last walked this stretch of the Leeds-Liverpool canal, at the start of a plan to walk the length of the canal in stages – a project completed in July the following year. Now I was reprising one of the most attractive stretches of the canal – between the small town of Burscough Bridge and Wigan – this time in the company of two friends, Bernie and Tommy. Continue reading “Walking the canal: the road to Wigan Pier”

Tag: Leeds-Liverpool canal

Walking the canal: Saltaire to Leeds

It was humid and already in the twenties by ten when I set off from Salt’s Mill at Saltaire at the start of the last leg of the Liverpool-Leeds canal walk. The heat was a reminder that, although there’s been a good deal of torrential rain this past week, the spring drought will result in the closure of a long stretch of the canal in a week’s time. The planned closure of almost half of Britain’s longest canal will take effect from Monday 2 August, and will close it for boating for 60 miles from Wigan to Gargrave in North Yorkshire. It’s all down to the extremely low level of the summit reservoirs that feed the canal at Barrowford and Foulridge. This was Barrowford reservoir when I passed in June.

From Saltaire, the canal skirts the northern edge of Shipley, and there are many reminders of the industrial past, with old warehouses and wool mills interspersed with recent residential developments.

Typical is this warehouse, purpose-built for loading barges on the canal, with its own basin and covered loading bay.

Shipley is where the former Bradford Canal (now filled in) met the Leeds – Liverpool Canal. Junction bridge is so-called because the canal junction was here (on the right, just through the bridge). The large building by the bridge on the right bank was the toll office and bargemen’s dormitory, known as the Barracks.

This is the time of year when two extremely successful invasive plants come to dominate places like roadsides, railway tracks and canal towpaths – the Himalayan Balsam and the more congenial Buddleia. Both are introductions from the Far East; the Balsam and its compatriot the Japanese Knotweed being the most troublesome. Buddleia was introduced to Britain from China in the 1890s. It is a highly successful coloniser, and really came into its own after the Second World War in bombeded areas of many cities. It is now widespread, especially on highly disturbed sites such as quarries, railway sidings and derelict building sites. There was plenty to be seen on this walk, especially along the last mile into Leeds city centre, where the canal is bordered by derelict sites smothered in Buddleia and Russian Vine.

Buddleia is named after Adam Buddle (1662–1715), an English cleric and botanist. Buddle didn’t discover the plant, but was commemorated by Linnaeus, who named the genus Buddleja in his honour. It seems to be a rare example of a beneficial invasive plant – a facilitator of species successions by providing a positive environment in which other species can establish. During the flowering season it is the favourite source of nectar for almost all native butterflies and in Britain it attracts more species than any native plants. The shrubs being highly attractive to insects, it encourages insectivorous birds to visit the sites to forage and in doing so they may inadvertently deliver seeds of other species in their faeces.

Leaving Shipley the canal stays close to the course of the river Aire, winding its way around the foot of the 500-foot densely wooded Buck Hill. The railway, which also says close for much of this stage, here cuts straight through the hill in a two-mile tunnel.

Halfway around the hill are Field locks, and the circuit of the hill is complete at Dobson locks, just outside Apperley Bridge.

Apperley Bridge is one of the posher areas of Bradford and certainly exuded a cheery charm on a sunny Saturday. There were tasteful new housing developments around the Apperley marina, while between the river Aire and the canal, playing fields were crowded with kids and parents involved in a local football tournament.

There’s a curious event associated with Apperley Bridge: on 29 February1824, watched by an estimated 30,000 people, John Wroe, also known as Wroe the Prophet, was baptised here, having announced in flyers that he would part the waters of the Aire like Moses.

Wroe was one of the most outrageous religious impostors known to history. The son of a worsted manufacturer at Bradford, Wroe, who was born in 1782, never received any education worth speaking of, and seems to have led an idle and purposeless life during his youth. In 1819 he had a serious illness, and after a seeming miraculous recovery Wroe started having visions or trances, which were usually preceded by his being struck blind and dumb. He joined the Southcottians, the followers of Joanna Southcott, at Leeds in 1820 and two years later claimed the succession as their leader.

After failing to part the waters of the river Aire at Apperley Bridge in 1824, Wroe continued his shameless ministry. In 1830 he announced that he had had ‘a comand from heaven to take seven virgins to cherish and comfort him’. Three local families duly provided the virgins from amongst their daughters and Wroe set off on a preaching tour with them. When he returned one of the girls was pregnant – this scandalized some of his followers and they attempted to hold an inquiry at which fighting broke out; pews, fittings, doors and windows were torn out and broken, and ‘pandemonium reigned’. Others were prepared to believe Wroe’s word that a Shiloh, or messiah would be born to the girl and great preparations were made for the birth. At Peel Park Museum, Salford, there used to be preserved the magnificent cradle made ready for the Shiloh’s reception. When the messiah was finally born it was a girl; at this point the Southcottians finally lost patience with Wroe and he was forced to leave town.

Another example of Wroe’s shameless behaviour is related by the Rev. S. Baring Gould in his work Yorkshire Oddities:

On one occasion Wroe announced that he was to lie in a trance for twelve days, and this beginning, people came from far and near to see him. At the foot of his bed was a basket in which visitors deposited gifts of money. At a fixed hour of the day all visitors were turned out, and the door of the house locked. One day Mrs Wroe went out and forgot to fasten the door behind her. Two neighbours, watching their opportunity, opened the door and looked within, to discover the Prophet sitting in the inglenook, supping very comfortably on beef-steak, pickled cabbage, and oat-cake. Notwithstanding this and many other exposures, Wroe continued to flourish. In 1854 he announced that the spirit had commanded him to build a house forthe believers, and to collect money for its erection from the latter, and subscriptions poured in readily. He bought a piece of land and commenced to build a great mansion, on which large sums of money were spent. When it was finished he conveyed it to the Society by will, but immediately made another will, revoking the first, and leaving his ill-gotten property to his son James.

Cultures change: in 2002 Bradford’s Hindu Cultural Society submitted a proposal to Bradford City Council to allow a small stretch of the River Aire at Apperley Bridge to be used for the scattering of ashes after a traditional Hindu funeral. A spokesman for the cultural society said, ‘Most of our community still travel to India for the purpose. But using the River Aire would allow those who can’t afford it to also scatter ashes’. I haven’t been able to discover whether approval was granted.

Leaving Apperley Bridge, there was a fine example of an old mill conversion into residential or office accommodation.

A little further on, a short, cheery woman with earphones passed me singing away to herself. The man on the canal bank fishing said, ‘She’s been past three times now singing to herself’. I asked why the chimney had a pointed top like a biro. He didn’t know.

I stopped for a pint and a ploughman’s at the Railway Inn at Rodley, another settlement associated with the woollen industry that at one time had fulling mills and scribbling mills powered by the fast-flowing waters of the Aire.

Setting off again after lunch, I was impressed by this imposing building on the opposite bank. Hailing the chap doing stone work in the grounds, I quickly discovered how you can draw the wrong conclusions. The building predates the canal, when it was a farm (perhaps an indication of the prosperity of wool farmers in the early 18th century). But with the arrival of the canal it had changed its function and become a brewery.

Pressing on, I pass Newlay and Forge locks, and with the river Aire so close it becomes apparent how high the level of the canal is being raised above the river.

A bit further on I notice, above the trees to the north, some sort of ruined tower. It’s Kirkstall Abbey, built between 1152 and 1182, and, though ruined, still substantially its full height and a unique example of early Cistercian architecture. Dissolution came in in 1539, and subsequently the Abbey and its lands were granted to Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, but reverted to the Crown in 1556 when he was burnt at the stake for treason.

Having been stripped of its roofs and windows, the abbey served as a quarry for local building works and housing for cattle, while the cloisters were planted as an orchard, and the gatehouse converted into a farmhouse. Grass, trees and ivy began to engulf the ruins, giving them a particularly rich quality of romantic beauty. The Abbey was painted by JMW Turner in 1824.

At Kirkstall itself, the old Mackeson brewery has been converted into a student hall of residence.

At Spring Garden lock the tower blocks of Leeds first come into view.

Just past Spring Garden lock there was a magnificent display of buddleia and water lilies.

At Oddy lock the lock-keeper was busy with maintenance work. There’s a mural here, called ‘Fragments from the post-industrial state’ by Graeme Willson. It was painted between 1981 and 1985 and has lasted very well. Willson is well known locally as a creator of public art and in 1978 he founded the Yorkshire Mural Artists group. His 1990 mural ‘Cornucopia’ on the Corn Exchange in Leeds has become a familiar landmark and won the Leeds Award for Architecture and Environment.

Just after Oddy lock stands this very impressive mill building – Leeds Mill – with elegant windows and curved bays at each end.

With less than a mile to go to the end of the canal, river, rail and canal are funnelled together, heading towards their common destination at Granary Wharf.

A really striking landmark here is the towers of the former Tower Works which produced pins and needles for the textile industry. The grade II listed structure is about to be redeveloped. The oldest of the three towers dates from 1864 and is based on the Torre del Commune, or Lamberti tower in Verona. Next to it is the Giotto Tower based on the Campanile of Florence Cathedral. The Giotto tower, which was in fact a chimney, is about half the height of that in Florence and rather than the marble cladding it has a finish of red brick work and local Burmantoft tiles. The third tower looks plain by comparison but is believed to be based on one of the towers of San Gimignano in Tuscany.

Towering over the second lock on the canal, Office lock, is Bridgewater Place, the tallest building in Yorkshire.

Next to the lock is the Canal Company office with the lock-keeper’s house to rear. The Canal Office building is listed and was built after the completion of the canal in 1816 (the canal from Leeds to Gargrave was completed by 1777, but there was a long delay in the completion through to Liverpool due to a lack of funds).

Finally, I arrive at Granary Wharf, the canal basin at the end of the canal. There has been a great deal of redevelopment here in recent years, with new buildings housing office, residential and retail units.

Granary Wharf represents the heart of the industrial revolution in Leeds, since the canal triggered the growth of Leeds as an industrial city. The earliest building in this area is the canal warehouse (below, left) built to a design by canal engineer Robert Owen in 1776, in time for the canal opening as far as Gargrave. In the area between the canal and the railway viaduct are a couple of small docks, now the focal points of the redevelopment of the area. These docks were used for repairing boats.

In the centre of the photo above is Candle House, a striking 23-storey round tower containing apartments, named after the candle and tallow packing warehouses that were previously located on the site. To the right is the new City Inn hotel.

I walked out across the footbridge over the river Aire to take this photo of the first lock – River lock – which begins the process of lifting the canal above the floor of the river valley. Behind me, a man dived off the Victoria Bridge into the river. This is a Grade 2 listed structure,built by George Leather Junior, engineer of the Aire and Calder Navigation between 1837 and 1839.

With the long walk finally over I wandered into the city centre through the railway arches known locally as the ‘Dark Arches’. They reminded me, in a rather bizarre way, of arriving in Orvieto, the Umbrian hill-town, where, after parking your car at the foot of the sheer cliffs that the town is built on, you enter the town via a series of tunnels and underground passageways.

When the railway arrived in Leeds, New Station was constructed on a large viaduct spanning the River Aire. Beneath the station and the tracks a series of arches were built with passageways connecting them, and many of these vaults were used for handling goods from the railway or nearby canal. These days they seem to be used mainly for car parking.

Next: Envoi

Walking the canal: Skipton to Saltaire

From Skipton, the canal wends its way along the valley of the river Aire, and for a good part of the way the towpath is wide and metalled so I was able to make good progress and cover 16 miles to Saltaire. Now just one leg of 13 miles remains before I reach the eastern end in Leeds.

Yesterday, like much of the past 10 days, was warm and sunny and the countryside was pleasant, though as far as Farnhill and Kildwick this is a noisy stretch, with the roar of the A629 to Keighley a constant presence.

Upper Airedale is a flat, wide valley here, bounded by tall steep hills and moorlands – especially to the north, where the fells stretch off towards Ilkely Moor. The canal hugs the hillside just above the valley floor, providing a lock-free pound that extends for the full 17 miles from Skipton to Bingley. The line of the canal was laid out along the Aire valley by James Brindley, one of the greatest of the canal builders. The canal passes by a series of villages – Bradley, Kildwick, Silsden – each showing evidence of the impact that the canal must have had on this largely agricultural area, with old mill buildings, particularly in Silsden.

At Hamblethorpe swing bridge, just past Bradley, there is a sudden jolt that pulls you back to a tragic moment in the past – a memorial to seven Polish RAF airmen who died when a training flight crashed here in September 1943. The men had escaped Poland in 1939 during the German invasion, and they enlisted with the RAF, which raised ten squadrons made up entirely of Polish personnel.

With each successive stage of the walk this year, the countryside has become steadily more parched, as rainfall has been scarce here, as well as in the north-west, for most of the spring and early summer. Just past midsummer, the banks and hedgerows begin to lose their colour anyway – though the flowers of the elderbery and dog roses provide splashes of colour.

At Farnhill the canal -passes through woods before emerging at the village where canalside industrial buildings have been converted to residential use.

Kildwick is the next village – all Yorkshire stone and steep streets spilling down the hillside to the canal, one of which runs under the canal.

Silsden is another, larger, stone-built industrial town. Generally an agricultural area, industry came with the canal and the Industrial Revolution. The town hosted a number of mills, none of which now operate in their original form. There is still industry in the town, some in old mill buildings and some in a new industrial estate between the town and the river.

I stopped at the Bridge Inn at Silsden, which appeared to be a converted end-terrace house. Certainly entering the bar was like walking into someone’s living room, with a small bar on the far wall. The room was draped in England flags and posters – at first the landlady said she couldn’t offer me food, as she was only doing it during half-time (this was the day of the England-Slovenia World Cup match). But she made me a fine cheese sandwich and I set outside with a pint of Black Sheep Ale from the independent brewery of the same name in Masham.

Apparently, the origins of the pub go back to the 1600s when ale was brewed at a farmhouse here. An inn developed in the early 1700s when it was first known as the Coach and Horses, and then the Boot and Shoe Inn. There is an old sign dated 1799, depicting a boot and shoe, over the original inn doorway, which can be seen now from the beer garden. It also bears the initials I S L, which refers to the Longbottom family who had a long connection with the inn. An 1822 trade directory lists John Longbottom as victualler. The canal was dug through Silsden between 1769 and 1773 and eventually, in 1826, a new road (now known as Keighley Road) was built at the other side of the inn, along with a bridge going over the canal. This meant the inn had to extend upwards and a new front door was created at the roadside.

From here the canal gains a decidedly suburban feel – the towpath is widened, level and metalled, with plenty of cyclists taking advantage of it – and the canal is fringed, along many stretches, by housing, much of it recently-developed. But this is still very attractive walking.

The canal wends its way around the outskirts of Keighley, and soon I arrive at one of the great sights of the canal – the Bingley staircase. An 18th century engineering masterpiece, the staircase comes in two parts – the Five Rise and Three Rise locks. These five locks operate as a staircase no intermediate pounds, in which the lower gate of one lock forms the upper gate of the next. The locks are supervised by a lock keeper and are closed at night.

The 5-rise is the steepest flight of locks in the UK, with a gradient of about 1 in 5 or a total fall of 60 feet (look at that drop in the photo above!).

The lock system was designed by John Longbotham of Halifax and built in 1774 by local Stonemasons : Barnabus Morvill, Jonathan Farrar, William Wild all of Bingley and John Sugden from Wilsden. The locks raise boats 59ft 2in over a distance of 320ft.

When the Bingley staircase opened on 12 March 1774 it was a major feat of engineering. This meant that the canal from Gargrave to Leeds was now open to traffic, and a crowd of 30,000 people turned out to celebrate. The first boat down the Five Rise Locks took just 28 minutes. This must have been phenomenal: when I asked some people waiting to enter the staircase yesterday how long it usually took, they said ‘an hour to an hour and a half’.

It’s slow because all five locks must be ‘set’ before beginning passage. For a journey upwards, the bottom lock must be empty, with all the others full: the reverse is the case for a boat descending.

The opening of the staircase in 1774 was given full coverage in The Leeds Intelligencer:

“From Bingley to about 3 miles downwards the noblest works of the kind are exhibited viz: A five fold, a three fold and a single lock, making together a fall of 120 feet; a large aqueduct bridge of seven arches over the River Aire and an aqueduct and banking over the Shipley valley ……. This joyful and much wished for event was welcomed with the ringing of Bingley bells, a band of music, the firing of guns by the neighbouring Militia, the shouts of spectators, and all the marks of satisfaction that so important an acquisition merits”.

Adjoining the Three Rise locks is the mill owned by the Damart company – famous for manufacturing a large proportion of the thermal underwear worn in the UK.

Further along is another example of the successful conversion of an old mill building into residential apartments overlooking the canal.

A little further along is bridge 205 – Scourer Bridge – an attractive structure that is a grade II listed building. The citation describes it as ‘Hammer-dressed stone. Single horse-shoe elliptical arch with dressed and chamfered voussoirs. Coped parapet aligned to the slope of the hill’.

Next is Dowley Gap, with more locks and an aqueduct that carries the canal over the river Aire.

Another couple of miles and I arrived at Saltaire, named after Sir Titus Salt who built a textile mill here in 1853, along with a model village for the mill-workers. Salt moved his entire business (five separate mills) from Bradford to this site partly to provide improved conditions for his workers compared to those in Bradford, and partly to site his large textile mill by a canal and a railway.

Titus Salt built neat stone houses for his workers, wash-houses with running water, bath-houses, a hospital, as well as an Institute for recreation and education, with a library, a reading room, a concert hall, billiard room, science laboratory and gymnasium. The village also provided a school for the children of the workers, almshouses, allotments, a park and a boathouse.

In 2001, Saltaire was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. The buildings belonging to the model village are individually listed, with the highest level of protection being given to the Congregational Church which is listed grade I. At the moment it’s undergoing renovation and is surrounded by screens and scaffolding.

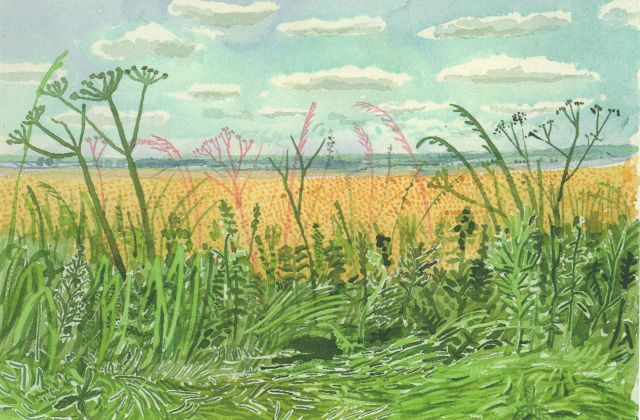

Salts Mill closed in 1986, and in the following year the late Jonathan Silver bought it and began renovating it. Today it houses a mixture of business, retail and residential units, with the main attraction being the 1853 Gallery, given over to the work of David Hockney, who was born in Bradford.

Jonathan Silver had met Hockney back in the sixties and approached him about displaying his work in the Mill. Hockney agreed, and the Gallery now displays paintings, drawings, photomontages and stage sets by Hockney. Currently there is a large display of opera sets created by Hockney, as well as reproductions of a recent series of water colours of Yorkshire landscapes in midsummer.

There are various shops, including a superb bookshop, plus restaurants and a cafe where I restored my energy levels with an excellent giant scone.

Finally, it was time to catch the train back to Skipton along Airedale line: comfortable, quiet and fast, and with clear travel announcements at every stop. Now only 13 miles remain before the journey ends in Leeds.

Walking the canal: East Marton to Skipton

It was hot already at ten in the morning when I set off from the little village of East Marton on the most beautiful leg of the canal walk so far. This stretch was an amble through an outstanding landscape with fine views across rolling fields and hillocks to distant rugged hills.

East Marton comprises a picturesque cluster of buildings, with pub, restaurant and an extensive stables and livery yard where horses were being exercised and groomed. The first stretch is green and tranquil as the canal pushes through a heavily-wooded cutting.

This stretch of the towpath actually forms a section of the Pennine Way. It must come as a relief to those walking that toughest of long-distance paths.

I was noting how, even in the two weeks since my last canal walk, the flowers have changed: though the hawthorn is still ubiquitous, now the dog-rose, yellow flag and birdsfoot trefoil are making their presence felt.

Heading towards Gargrave, the canal winds in extravagent loops through humpy hills smothered in buttercups (those drumlins again).

At Bank Newton, six locks lower the canal into Upper Airedale. This was once an important base for canal maintenance to keep this particular length of the canal in full working order, with carpenter’s workshops and other buildings that are now converted into houses.

The first part of the Leeds-Liverpool canal to open was the lock-free section from Skipton to Bingley, in 1773. The datestone on the lock-keeper’s cottage indicates that the canal reached here 18 years later.

Close to the village of Gargrave an aqueduct carries the canal over the river Aire, flowing in from the north. From here, the canal will follow the Aire valley down to Leeds, accompanied by the railway line from Carlisle and Settle.

At Gargrave, the Pennine Way leaves the canal to head north towards Malham. Here the canal enters the Yorkshire dales National Park.

There is an interesting account of the impact that the canal had on this part of the world on Out of Oblivion, a website that documents change in the cultural landscape of the Yorkshire Dales:

In the 1760s, Yorkshire merchants were keen to improve the supply of limestone from the Craven Dales to the farmland and towns of the West Riding. The limestone, once burnt and turned into lime was needed to improve yields from marginal agricultural land while the mortar produced from the same source went to build taller weaving sheds and houses for mill workers. They conceived the idea of building a canal from Leeds, up the Aire valley, to Gargrave. They also saw the possibilities of extending the canal to Liverpool in order to take advantage of the trade in textiles to the growing colonial markets in Africa and America…

The effect on the southern Dales of the arrival of the canal at Gargrave can not be overestimated. Although limestone was intended to have been the canal’s major traffic it turned out to be coal instead. Up until then coal for domestic and industrial use in the Dales had come from often remote collieries such as those above Threshfield or on Tan Hill. The state of the roads and the difficulty accessing many of these collieries meant that packhorses and to a lesser extent wheeled vehicles had been the only method of transporting it. Added to that, local coal was shaley and poor quality. The Leeds-Liverpool canal offered a viable alternative by being able to transport bulk materials over distance at a low cost. Better quality coal at cheaper prices was delivered to warehouses in Gargrave and from there the coal was collected by carriers who delivered it throughout Wharfedale and beyond. The Cupola smelt mill on Grassington Moor was now assured of a regular supply of good quality fuel. Domestic users had an alternative to collecting wood or cutting and drying peat. During much of the nineteenth century over one million tons of coal a year was transported on the canal. This contrasted with around 50,000 tons of limestone per year.

The Leeds & Liverpool Canal was an efficient carrier of both bulk raw materials and merchandise such as groceries, beer and machinery. It continued to compete successfully along its length with railways until road transport began to take off after the First World War. Coal remained the main cargo, but as factories began to turn from steam power to electricity demand for it fell away until finally in 1972 the last regular commercial traffic ceased.

Approaching Skipton,in the meadows beside the canal, hay had been cut and this was attracting a great many birds. A heron flew up just in front of me, and curlews were noisily investigating the mounds of cut grass. I was surprised to see a pair of oystercatchers so far inland. In the hot midday sun, martins swooped to catch insects over the canal’s still water.

Although the canal had been busy with barges, I had encountered hardly a soul on the towpath. It was quite a shock, then, to arrive in Skipton which was heaving and bustling with day-trippers, a goodly proportion of whom were decidedly elderly.

Skipton is a very pleasant little town. The area around the canal basin appears to have been constructed all of a piece around the time that the canal arrived in 1773 . This gives the buildings, bridges and embankments a pleasing homegeneity, constructed largely from glowing yorkshire stone. The Leeds Intelligencer reported on 8 April 1773:

“On Thursday last, that part of the Grand Canal from Bingley to Skipton was opened, and two boats laden with coals arrived at the last mentioned place, which were sold at half the price they have hitherto given for that most necessary convenience of life, which is a recent instance, among other, of the great use of canals in general. On which occasion the bells were set ringing at Skipton; there were also bonfires, illuminations, and other demonstrations of joy.”

The Springs Branch is a short section that branches off from the main canal to enter a wooded ravine bounded by an escarpment surmounted by Skipton Castle.

Lord Thanet in Skipton owned both Skipton Castle and local limestone quarries. He proposed the construction of a quarter mile branch canal to connect the quarries with the new Leeds Liverpool Canal. An Act was passed in 1773 to enable construction to go ahead and the branch canal was built quickly.

Skipton has a long history, with its name deriving from the Saxon word for sheep and meaning ‘sheep town’. Settled by sheep farmers as long ago as the 7th century, the town has an entry in the Domesday Book, and Skipton Castle was built around 1090 by Robert de Romille, who came over from Normandy with William I in 1066. But it was the arrival of the Leeds-Liverpool canal that boosted the town’s fortunes and Skipton boomed during the Industrial Revolution, with cloth making becoming the major activity.

I walked up Springs Branch, past the waterfall where Eller beck cascades into the canal, to the rock face where the canal branch ends abruptly. This is where the limestone was once quarried.

Continuing beyond the canal branch, a path takes you into Skipton Woods. I should have been here a few weeks ago: everywhere I looked, as far as the eye could see, the woodland floor was thick with wild garlic, but the recent blossoms were faded and gone. The wood is managed by the Woodland Trust, which states on their website:

A magical land in the heart of town – that’s one way to describe Skipton Woods, a woodland haven by one of Britain’s best preserved, most popular medieval castles. The wood’s links with the castle date back at least 1,000 years. Most of this ancient woodland is dominated by ash but the occasional sycamore, beech, Scots pine, Norway spruce and hornbeam indicate a greater variety in the past. The woods are renowned for their vivid displays of bluebells and wild garlic and sustain five species of bat. Green and greater spotted woodpeckers add their colour, while kingfisher and heron may be seen fishing the waterways.

The woods were originally used by Skipton Castle primarily for hunting and fishing, although during the 18th and 19th centuries, the woods were also used to provide timber, building stone and water. The timber and stone was moved out of the woods via Springs Canal. The water was obtained by damming Eller Beck to form Long Dam, which in turn fed a small reservoir called Round Dam, also known as Mill Dam or Mill Pond. The water was used to power the former sawmill and corn mill located by the castle. Public access to the woods was only allowed by the owners of the castle in 1971.

Someone was here at the beginning of May this year and made a video of it:

By the canal basin there’s a striking statue of the Yorkshire fast bowler, Fred Trueman, that was unveiled a few months back. It was created by Yorkshire sculptor Graham Ibbeson, from a studio in his back garden in Barnsley, with the blessing of Trueman’s widow Veronica. Trueman made his Yorkshire first-class debut in 1949 and went on to play 459 games for the county, notching up 1,745 wickets. In 67 Test matches for England he took 307 wickets, and retired in 1972 for a career in the media. He died in 2006, aged 75. The Truemans made the Yorkshire Dales their home in the 1970s, although Fred himself was born in Stainton, a village between Rotherham and Doncaster.

I walked to the outskirts of Skipton, before turning back to catch the X80 bus that would drop me back in East Marton. I am now over 100 miles from Liverpool.

Next: Skipton to Saltaire

Walking the Canal: Nelson to East Marton

I set off from bridge 141D at Nelson on a bright sunny morning and the temperature rose steadily as the day progressed. The countryside was smothered in buttercups and hawthorn: has the blossom been particularly striking this year, after the hard winter and cold spring?

A couple of miles further on the M65 motorway bridge piggybacks over the original 19th century canal bridge. Then, with Pendle Hill’s distinctive form to the north, it’s into beautiful Pennine countryside, heading towards the pretty Barrowford locks.

At the bottom lock, work was being carried out to repair damage to the lock floor which had caused an escape of water. The lock was completely drained and further up, above the top lock, there was a considerable tailback of narrowboats, held up by the stoppage which, chatting with one of the navigators, I discovered had lasted several days. He didn’t seem to mind – being parked up in beautiful countryside with good weather to boot!

Barrowford locks and lock-keeper’s cottage form a very pretty complex, and the lock-keeper enterprisingly sells second-hand books and local ice cream. A little further on, the canal passes Barrowford Reservoir, in which surplus water is stored.

Another mile brings you to the entrance to the Foulridge tunnel, which is just under a mile long. It opened in 1796, after five years of excavations. Because the tunnel is so long and there is no towpath for a horse to pull the barges through, between 1880 and 1937 a steam boat tugged barges through. Before 1880 men would ‘leg it’ through the tunnel, lying on their backs and pushing the barge through by walking along the ceiling of the tunnel. In the Hole-in-the-Corner pub, near the far entrance, is a picture of a cow named Buttercup that fell into the canal in 1912 and, instead of just wading out, decided to swim the entire length of the tunnel before being rescued. It is said she was taken to the pub and revived with a pint.

A little further on, I noticed a ventilation shaft for the tunnel in a field of buttercups. Then the walker’s route skirts the large reservoir that feeds the canal before eventually bringing you into the village of Foulridge. Although just a small village, Foulridge was to become an important centre on the canal, as it was here that the water supply was organised. Water came not just from reservoirs, but also from streams feeding into the summit level. By 1879, around 90 boats were passing through the tunnel each week, and the leggers were replaced by the steam tug in 1882. But by 1930 there were only 13 boats using the tug each week and the service ended in 1934.

When I was looking at the today’s route I imagined that Foulridge had gained its name from being some desolate, windswept Pennine crag. Not so: the fine countryside here is far from bleak, and the place-name has a totally different etymology. It’s actually pronounced ‘foalridge’, and derives from the Anglo-Saxon words for ‘foal’ and ‘ridge’, suggesting that this was a renowned horse-rearing area in those days.

Foulridge Wharf was built in 1815 to bring American cotton, limestone and coal to Colne. Now it has a pleasant cafe and is a stopping off place for those travelling the canal.

From here I walked on another mile or so before taking a break for lunch and a pint at the Anchor Inn, near Salterford. This canalside pub is unusual because when the road and bridge were built outside, another storey had to be built on, so the original upstairs of the old pub is now the present pub, the original pub is now the cellar and it has a second cellar, which has stalactites and stalagmites created as a result of water leaking through from the canal.

While I was having lunch in the beer garden, this chap was practising the old craft of dry-stone walling, repairing damage to the pub’s boundary wall. The roots of drystone walling as a method of enclosing fields lie at least as far back as the Iron Age. Drystone walls are not merely features of agricultural interest; they are in a sense, living history; a legacy of the movement towards enclosure of common farming and grazing land. Most of the drystone walls we see today are products of the post-medieval move toward enclosure. I sat and mused on how many tens of thousands of miles of dry stone walls there must be in the British Isles – and how many man-hours of labour went into their construction.

Just past the bridge at the pub are two of the few remaining tow line rollers along the UK canal network. When the canal turned a sharp bend, as here, it was difficult for a horse-drawn boat to steer; and the tow rope would pull the boat into the bank instead of around the corner. To stop this from happening, vertical rollers were fitted to upright wooden posts, the tow rope passing across the rollers and keeping the pull on the boat such that it was not a problem for the boatman steering the boat.

Tow lines would rub against the bridge arch after the horse had passed underneath. This caused grooves tobe worn into the stonework. Vertical wooden rollers were fitted to most bridges to stop such wear. The iron bearings of the wooden roller guard irons often survive, though most of the rollers have disappeared. Here they have been renewed.

For the next couple of miles the canal meanders along the outskirts of Barnoldswick, the highest town on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Barnoldswick remained a small village until the arrival of the canal, and later the (now closed) railway, spurred the development of the old woollen industry, and helped it to become a major cotton town. The engine of the last mill to be built in Barnoldswick, Bancroft Mill, has been preserved and is now open as a tourist attraction.

Today, Barnoldswick is home to Silentnight Beds, the UK’s largest manufacturer of beds and mattresses, and Rolls Royce. The model number of many Rolls Royce jet engines start with the initials RB which stands for Rolls Barnoldswick.

At the northern edge of the town, the Greenberfield locks, opened in 1794, have been voted the best kept in the country. Greenberfield is the highest point on the canal. From here, it’s all downhill to Leeds!

The original function of the canal here was to carry limestone from several local quarries, one of which was located just above this lock. The quarry closed in the late-nineteenth century and was filled in.

As the afternoon wore on, we were all hotter and thirstier. Walking in a bucolic haze through a landscape of rounded hillocks often topped by clumps of trees (such as Copy Hill, above), all that industrial activity seemed long ago.

These rounded hillocks are drumlins, formed when melting glaciers deposited rock debris and then moulded the piles into theses oval hillocks characteristic of this part of the Yorkshire Dales.

Finally, I arrived at the curious Double-Arched bridge at East Marton. This odd-looking structure carries the busy A59 road over the canal. It would appear that after the original bridge was built the height of the road was raised to eliminate a dip, and as a consequence a second bridge was built on top of the first. And as I climbed steps to the road to catch the bus back to Nelson, there was the milestone – 38 miles to go!

Next: East Marton to Skipton

Walking the Canal: Accrington, Burnley and Nelson

Yesterday saw another leg of the canal walk completed: arriving at Nelson, there are now less than 50 miles to go to Leeds. It was a dry, warm day, sometimes overcast but mainly sunny. Leaving Clayton-le-Moors, the canal winds its way eastwards through the Calder valley. To the north there are views across to the Pennine fells, most notably Pendle Hill. Along this stretch there were many derelict or ruined farm buildings. Further on, the theme would continue, with a succession of derelict or ruined industrial buildings, probably reflecting the decline of, firstly, sheep farming supplying the woollen industry, and then the closure of the textile mills themselves.

There were still some signs of sheep farming, though.

To the south, the M65 motorway is never far away – largely out of sight, but audible as a hiss or, when closer, a dull background roar.

Under one of the motorway bridges, over on the far side of the canal, there was this extensive and painterly graffiti.

A little further along I photographed art of a different sort. This is a style of painting called Narrowboat Art, which originated on the canals in England during the 19th Century. The earliest boats did not carry this style of decoration, but it began to appear once wives and children joined the boatmen as residents on the narrowboats (because competition from the railways meant they had to give up their cottages and move completely onto the boats).

The website Canalia explains:

The life of the working boatmen and women was very tough, with the entire family living in an aft boatmans cabin around 6 feet in length. Boat children recieved little or no education and were expected to assist with the heavy work from a young age, often leading the horse or mule which pulled the boat for many miles each day.

Almost every single part of working narrowboats and their equipment was painted. The most distinctive aspects of Narrowboat Art are the roses, painted in bright primary colours, together with panels depicting castles. The reasons why roses and castles predominate are unclear. So ‘Roses and Castles’ is the common name for this folk art, which would embellish the outside of the boat and its equipment, entwined with lettering on the cabin side, on the rudder and even appeared on horse harnesses and feed tins.

This guy was carrying on a scrap metal business on two narrow boats.

Just north of Accrington the canal diappears into the Gannow Tunnel, re-emerging after a third of a mile to cross the M65 by acqueduct.

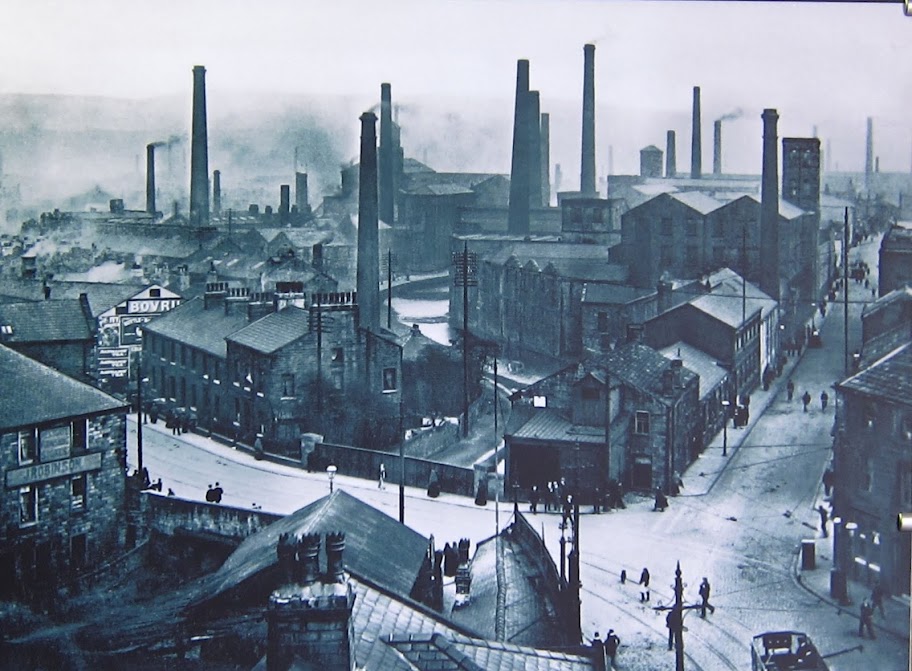

The canal now enters an industrial stretch that leads into Burnley, and there’s a real sense of how the canal was once a main artery for the town and its industries, though now most of these buildings lie derelict.

The area between bridge 130 and Burnley Wharf is known as the Weavers’ Triangle, and was once at the heart of Burnley’s textile industry. The name was first used in the 1970s, as interest developed in preserving Burnley’s industrial heritage. Coming from Liverpool, the first significant industrial building that you encounter is Slater Terrace, built by the millowner George slater in the late 1840s.

What’s unique about this building – currently in a state of dereliction – is that it combines canal-side warehousing with eleven two-storey houses above, their front doors opening on to an iron landing jutting out over the canal.

The warehouse would store raw cotton which had been brought up the canal from Liverpool, while warehouse or mill workers would live in the houses. Although built to a good standard, they soon became overcrowded and were last inhabited in 1900, after which they were converted to industrial use.

At Burnley Wharf there is an excellent Visitors’ Centre in the old toll house and wharf master’s house. While the ground floor rooms provide an insight into the daily routine and home life of the wharf master, the basement has been set out to show what home life was like for mill workers a hundred years ago.

The area now known as the Weavers’ Triangle is the best remaining Victorian industrial district in the town – and possibly the country. The factories here line the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, constructed through Burnley between 1796 and 1801, which provided transport for the raw cotton and finished cloth, and also, after 1842, water for the mill boilers. The industrial architecture of the area has a solid, dignified and massive appearance, in a simple, functional

tradition, with walls of local sandstone and stone or slate roofs.

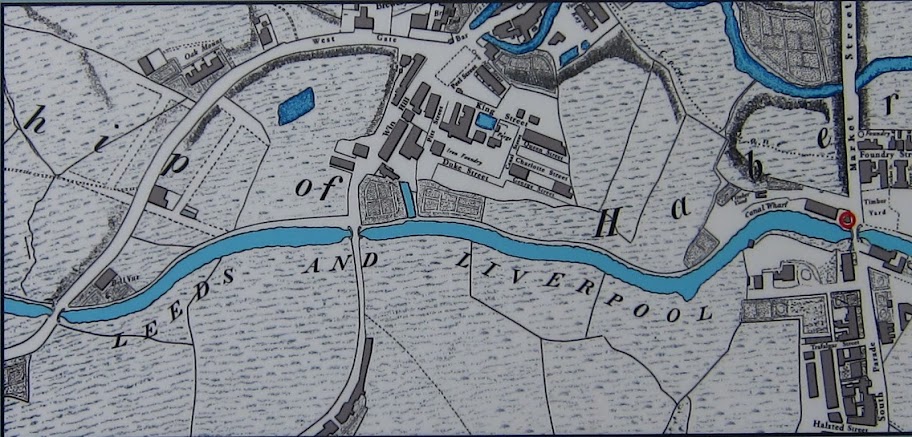

One display shows, in a series of maps, how rapidly the area developed in the 19th century, the first showing the Weavers’ Triangle area of Burnley in 1827:

Then in 1848:

And finally in its heyday in 1912:

There’s also an evocative photo of the area in 1910, looking for the world like an LS Lowry urban landscape:

The Wharfmaster’s House, which is now the Weavers’ Triangle Visitor Centre, was built in 1878. The warehouses on Burnley Wharf have been converted to modern use: there were some very attractive-looking office spaces and the Inn on the Wharf, a pub in which the original beams, stonework and flagstones have been preserved, and where I had an excellent lunch (whitebait starter and delicious Shropshire Blue cheese ciabatta-style baguette) accompanied by a pint of Old Speckled Hen.

Burnley’s textile industry dates from the Middle Ages, when a fulling mill was built on the banks of the Brun in 1296. Wool was the main cloth made in the area until the end of the 18th century, when it was superseded by cotton. The first cotton mills were for spinning – weaving being done in the home. By 1850, weaving had also become a factory industry and East Lancashire was taking the lead in improving the power loom. After 1870, the weaving side of the industry expanded at the expense of spinning, which became concentrated in the south of the county. By the end of the century, Burnley was the leading cotton-weaving town in the world. The peak was reached in 1913 when the district had over 100,000 looms.

The ‘Straight Mile’ is the name given to the Burnley Embankment, which carries the canal across the valley of the River Calder. The embankment was constructed between 1796 and 1801, by an army of navvies using spoil brought by boat

from the canal cutting to the north of Burnley. Earlier, observing the way that the canal maintained a level course by being raised on an embankment above the surrounding fields, I had wondered – why don’t canals leak? The answer, apparently, is a process called ‘puddling’ – heavy clay was used to line the bed of the canal. Nowadays, of course, concrete would be used.

Construction of the Embankment meant the Calder valley could be traversed by the canal without the need for two systems of locks. Walking along the 60 feet high embankment gives dramatic views across the rooftops of the town to the surrounding hills. Half-way along the embankment, the canal crosses Yorkshire Street on an aqueduct, known locally as ‘t’ Culvert’. It was constructed in 1926 to replace the original one built in the 1790s.

Although the Embankment and the surrounding area have been tidied up to provide an attractive promenade and shopping district, further on there are more signs of the decayed industrial past.

But the surrounding landscape is beautiful, with Pendle Hill dominating the views.

Five more miles of towpath brings you to Nelson, another town that grew as a result of the arrival of the canal in 1796. It takes its name from an inn called the Lord Nelson around which the town started to grow. Like Burnley, its economy was based on cotton weaving. Later the town became noted for the production of confectionery as well, including Jelly Babies and Victory Vs. These industries have long gone, leaving the town with high unemployment.

Driving home along the M65, the sea at Morecambe Bay was a glinting gleam of silver in the evening sun. On the stereo: Paul Weller, Wake Up The Nation, and the Rolling Stones, Exile on Main Street.

Next: Nelson to East Marton

Walking the canal: Blackburn to Clayton-le-Moors

There’s a place that I seek when I need somewhere to hide

It’s a place that I go when I need some peace of mind

Don’t seem to mind if I smile, don’t seem to care if I don’tI’m a fly upon the wall, I’m in company and I am alone

There’s a message on the bridge in graffiti-written words

And it reads as an answer or it reads as nothing at all

Don’t seem to mind if I show, don’t seem to care if I don’tI’m a bird upon the bridge, I look out and I look in

When the city’s back is turned it looks a lot like this

When a mind begins to burn it needs a place like this

Don’t seem to mind if I’m right, don’t seem to care if I’m wrong

I’m the dirty river flow, I need you so that I can let go

– Emily Barker,’The Greenway’, from the album Despite The Snow

Got started again on the canal walk. A gentle seven mile stage from the outskirts of Blackburn to Clayton-le-Moors, via the villages of Rishton and Church, to ease me back in, and attune the dog to hiking.

We started off from the car park of PC World at Whitebirk Bridge. The photo above gives a sense of the juxtaposition of urban and country landscapes here: a retail park to the left, pylons striding down the centre and open farmland to the right, with the wild Pennine moors in the distance ahead. All the photos posted today were taken on my new Canon Powershot S90 which produces pretty impressive results for such a small, pocketable camera.

There was a nippy breeze blowing from the east, keeping the temperature down, but it was a bright and sunny day nonetheless. But there’s still not much colour up here: after the coldest winter for many a long year, these coltsfoot and celandine, one pussy willow and a lone flowering hawthorn were about all.

A tractor hauling a scarifier made turns around a field by the canal. Beyond, there were distant views of Pendle Hill and Lancashire fell villages strung out along the hillsides.

Rishton first became an important textile town in the 19th century, with cotton being brought in along the canal from Liverpool, and it was also the first place where calico was woven on an industrial scale, with 10 mills being in operation. All have now gone, or are in ruins.

A little further along the canal at Church, the family of Sir Robert Peel established an industrial community based on calico printing, with terraced housing, mills and a parish church featuring two windows designed by Edward Burne Jones. At Simpson’s Bridge, there is a fine old wharf building – now in a serious state of dereliction – with a large central arch.

Just before Church you reach the halfway marker on the canal – with 63.5 more miles to go to Leeds.

After an encounter between dog and horse, we arrived at Bridge 114A, and I got a decent fish and chips with mushy peas at the Hare and Hounds. The dog slumbered, and I learnt that while we’d progressed seven miles the nation’s airports had been clogged with people going nowhere as the cloud of volcanic ash from the eruption in Iceland grounded all flights over northern Europe.

Footnote: I later discovered that Nimrod, the osprey whose annual migrations I have followed on the Highland Foundation for Wildlife site, was at one point somewhere over the canal at Chorley, heading back at 3000 feet to his summer home in northern Scotland after wintering in Gambia.

Walking the canal: Wigan to Blackburn

And the seasons they go round and round…

It’s been a while since I broke off the walk at Wigan top lock and in that time summer has come, and now is on the wane. The towpath is lined now with rose hips, rose bay willow herb, elder berries, sloes and blackberries; I crammed some of this black honey of summer into my mouth to spur me on towards Johnson’s Hillock and the Top Lock pub:

When the blackberries hang

swollen in the woods, in the brambles

nobody owns, I spend

all day among the high

branches, reaching

my ripped arms, thinking

of nothing, cramming

the black honey of summer

into my mouth; all day my body

accepts what it is. In the dark

creeks that run by there is

this thick paw of my life darting among

the black bells, the leaves; there is

this happy tongue.

– Mary Oliver: August

On the telephone wires, swallows were gathering, perhaps preparing for the long journey south that they will embark upon sometime in the next few weeks.

However, one of the dominant memories of this particular walk will be the sight of banks and masses of the pesky Himalayan balsam – it was there lining the tracks on the railway line to Wigan and back, along the tow bath and in drifts extending through the woods adjoining, and lining the road on the bus journey back to Wigan.

This was perhaps the least satisfying stage of the walk – partly because a good 50% of the time – from Adlington, past Chorley and on into Blackburn – the canal is accompanied by motorway, the roar of traffic constantly present though hidden from view by woodland. And it’s the way that the canal burrows deep through the tree cover here that is also unsatisfactory – it was only on the bus ride back from Blackburn to Chorley that I got any real sense of the surrounding countryside: the moorland views towards Rivington Pike, with the stone terraces of the 19th century mill towns climbing through the hills.

I picked up the trail again above Wigan top lock, where the canal runs along the fringe of Haigh Country Park. Haigh Hall was once the seat of the Earl of Balcarres who profited from the wealth generated by the coal seams and the Haigh Iron Works which were developoed from the 1840s onwards. In the photo below, Haigh Hall can just be made out on the skyline.

On the stretch up towards Adlington I fell in with another walker, a local guy whose grandfather had worked as a boatman, who pointed out relics of the industrial past on the opposite bank – here was where coal was loaded, there signs of the textile industry; that house was once a pub that served the bargemen, and there was where the original railway line to Blackburn ran.

Approaching Chorley a 150-year-old spinning mill has been converted into a retail and leisure destination called Botany Bay. It has 5 floors selling collectables, furnishings, memorabilia, furniture and gifts.

There’s plenty of it anywhere along the canal, but on the Chorley to Blackburn stretch it was particularly marked: the magnetic attraction of the waterside for new housing developments. This was a striking example, just below the start of the locks at Johnson’s Hillock:

I worked my way up the locks at Johnson’s Hillock and stopped for lunch at the Top Lock pub.

The canal now turns northeast and flows along a secluded and often densely wooded valley at a height of over 350 feet above sea level. After a short while I reached Withnell Fold – a 19th century model village built to house workers at the paper mill, now demolished apart from its chimney.

As the industrial revolution of the 19th century expanded, more mills and workers were needed. Sites for these mills were largely dependent on a water supply and transport systems to bring raw materials in and produce out. Some mills were too far from centres of population so ‘colony’ villages had to be built nearby to house the workers: Withnell Fold village and Paper Mill were built on a green-field site in 1843. The owner and builder was Thomas Blinkhorn Parke (1823-1885), the son of Robert Park, a local Cotton Mill owner.

The Reading Room was built by Thomas Parke’s son, Henry and opened on 4 Oct 1890 for the benefit of the mill workers and their families. It was equipped with a billiard table, reading room with current periodicals, and upstairs a stage and concert hall with a sprung dance floor. Henry Parke wanted the building to ‘help young men gain general knowledge and help introduce less indifference to social questions’. He was a local benefactor and two of his best known achievements were to fund the first Public Library in Chorley in 1899 and also build Brinscall Baths (the first Public Baths in the area) in 1911. A sculpted tree trunk represents T.B. Parke, founder of the villlage.

The village school was also built by Henry Parke. The date-stone to the right of the main entrance door reads HTP 1897, his initials.

The terraces of stone cottages in the village square were built in 1843.

Withnell Fold Methodist Church is one of the later buildings to be constructed. It was built by Thomas Blinkhorn Parke in 1852 as a day school and Chapel combined.

I was musing over the many and varied names people give their canal boats – often something aspiring to a peaceful state of mind, a flower or a girl. But today I saw one named mirrlees and another called crossleys. Strange – they’re both places where my Dad worked – Mirrlee’s manufactured diesel engines at Hazel Grove, near Stockport and Crossley‘s were a motor vehicle manufacturer he worked for in Openshaw. Whatever. Here’s a boat called Topaz.

I trudged on towards Blackburn, the roar of the motorway constant on this stretch. At the Cherry Tree suburb, after roughly 16 miles I decided to call it a day and caught a bus back to Chorley that rattled through the stone-terraced hillside villages of Withnell, Brinscall and Wheelton; then a bus to Wigan and finally the two-car diesel that rattled and screetched its way back into Liverpool. I’d reached the towpath at ten that morning; I got home for 7:30. All the public transport was dead on time.

Walking the canal: Parbold to Wigan

Well I’ve been out walking

I don’t do that much talking these days

These days…

I’ll keep on moving

Things are bound to be improving these days

These days –

These days I sit on corner stones

And count the time in quarter tones to ten, my friend

Don’t confront me with my failures

I have not forgotten them

– Jackson Browne, These Days

For the first hour of this walk, the canal follows the valley of the river Douglas. The landscape changes after Parbold: we leave behind the Lancashire flatlands and move steadily towards higher ground. Up to Appley Bridge this is a lovely stretch, with the Douglas twisting alongside the densely-wooded canal through the valley surrounded by rolling hillls. It’s also the busiest stretch so far – bustling with cyclists, walkers, narrowboats, canoes and a school party of hikers.

The river Douglas, a tributary of the Ribble, rises on Winter Hill on the West Pennine Moors, and flows for 35 miles through the town centre of Wigan and into the Ribble estuary. Walking through the valley is to go back to the early period of canal-making when rivers like the Douglas were canalised, these navigations being the forerunners of the canal-building boom that began barely four decades later.

In 1712, Thomas Steers, the engineer who built Liverpool’s first dock, surveyed the Douglas and recommended that it be made accessible to ships, enabling the transport of coal from the coalfields around Wigan down to the Ribble, and onwards to Preston. The canalisation of the river was authorised by Parliament in 1720 and involved the construction of 13 locks. The navigation opened in 1742 but was bought out by the Leeds and Liverpool Canal Company in 1780 and abandoned by 1801, by which time the canal provided a better route to the River Ribble. Although abandoned for 200 years, traces of the navigation, including the remains of several locks, can apparently still be seen between Parbold and Gathurst.

And history moves on: the canals were soon superseded by the railways. Walking this stretch, you are reminded occasionally of this as, behind the trees, a train clatters past on the line, opened in the 1850s, that follows the course of the canal through the valley.

In the hedgerow there are scentless wild roses or dog roses, another maligned wildflower, regarded as a weed (‘canker blooms’, they were known as in Elizabethan times) and inferior to the fragrant garden rose. Shakespeare’s Sonnet 54 hinges on that comparison: the scent of the garden rose is the true mark of its beauty, and stands for the inner qualities of the “lovely youth”. Nobody prizes the dog rose, which is all outward show, but the true rose outlives itself, in that its petals can be used to make fragrant rosewater or as a perfume: ‘Of their sweet deaths, are sweetest odours made’.

O! how much more doth beauty beauteous seem

By that sweet ornament which truth doth give.

The rose looks fair, but fairer we it deem

For that sweet odour, which doth in it live.

The canker blooms have full as deep a dye

As the perfumed tincture of the roses,

Hang on such thorns, and play as wantonly

When summer’s breath their maskèd buds discloses:

But, for their virtue only is their show,

They live unwoo’d, and unrespected fade;

Die to themselves. Sweet roses do not so;

Of their sweet deaths, are sweetest odours made:

And so of you, beauteous and lovely youth,

When that shall fade, my verse distills your truth.

Appley Bridge is a small hamlet which was once quite industrial, with several quarries and clay pits for the Wigan brick company.

Just beyond Appley Bridge the canal passes under the M6 motorway, so this stretch has offered several layers of transport technology – from 18th century river navigation and then canal to 19th century railway and 20th century motorway.

Beyond Gathurst lies Crooke where I expected to be able to get a pint and a bite to eat at the Crooke Hall Inn. But oddly both this and the next canalside pub were closed, with signs indicating they only opened at 2.00. Very strange!

So I had to contine along the rather dreary stretch into Wigan, through wasteland and industrial units, passing the JJB stadium where Wigan Athletic play. Now, I thought, I’ll be able to get a lunchtime pint at the Orwell on Wigan Pier, a CAMRA pub of the year. But it was not to be. I arrived to find the place shuttered and empty – it closed in January 2009. A converted three-storey grain warehouse, The Orwell was seen as a key feature of the Wigan Pier redevelopment when it opened as a national tourist attraction in 1985. But the venue had struggled with the credit crunch, the decline in the pub trade and, particularly, the closure of the other major Wigan Pier attraction last summer: the museum of Victorian life, The Way We Were.

It seems that Wigan Council have pulled the plug on funding for these venues and has plans (if the credit crunch allows) for other developments here. The council argues that the heritage industry is not the draw it once was. Visitor numbers had been declining whilst the council subsidised the attractions at the Pier to the tune of £1.3m a year. The council now believes that the Pier’s future lies in a gradual move towards a cultural quarter for the 21st century rather than a series of heritage attractions looking back at the last century.

The original ‘Wigan pier’ was a tippler where wagons from a nearby colliery were unloaded into waiting barges on the canal. It was demolished in 1929. The pier joke is thought to have originated in a music hall act performed by George Formby Senior in which he talked of Wigan Pier in the same terms as the seaside pleasure piers in Blackpool and Southport. The replica tippler seen above was erected on the site of the old one when the area was redeveloped.

In 1937, Wigan Pier was immortalised in the title of George Orwell’s Left Book Club account of unemployment and desperate living and working conditions in the northern industrial areas. In the book, Orwell responded to criticism from the Manchester Guardian of ‘his wholesale vilification of humanity’. On the contrary, he says:

Mr. Orwell was set down in Wigan for quite a while and it did not inspire him with any wish to vilify humanity. He liked Wigan very much — the people, not the scenery. Indeed, he has only one fault to find with it, and that is in respect of the celebrated Wigan Pier, which he had set his heart on seeing. Alas! Wigan Pier had been demolished, and even the spot where it used to stand is no longer certain.

In another passage Orwell writes:

I remember a winter afternoon in the dreadful environs of Wigan. All round was the lunar landscape of slag-heaps, and to the north, through the passes, as it were, between the mountains of slag, you could see the factory chimneys sending out their plumes of smoke. The canal path was a mixture of cinders and frozen mud, criss-crossed by the imprints of innumerable clogs, and all round, as far as the slag-heaps in the distance, stretched the ‘flashes’ — pools of stagnant water that had seeped into the hollows caused by the subsidence of ancient pits. It was horribly cold. The ‘flashes’ were covered with ice the colour of raw umber, the bargemen were muffled to the eyes in sacks, the lock gates wore beards of ice. It seemed a world from which vegetation had been banished; nothing existed except smoke, shale, ice, mud, ashes, and foul water.

The Wigan Terminus Warehouses (above) were built in 1777 and refurbished in the 1980s. For a while this was the end of the canal: barges could moor inside the building and off-load directly into the warehouse.

I’d imagined that Wigan only emerged as a township with the industrial revolution, but as early as the 13th century it was one of four boroughs in Lancashire with Royal charters, the others being Lancaster, Liverpool, and Preston. During the Industrial Revolution Wigan experienced dramatic economic expansion and a rapid rise in the population. Although porcelain manufacture and clock making had been major industries in the town, Wigan now grew as a major mill town and coal mining district.

Here’s a painting that evokes that period: The Dinner Hour – Wigan is one of the few paintings by Eyre Crowe that is well known today, and one of the few paintings of his on public display (at Manchester Art Gallery). It is likely that the painting was inspired by a visit to the cotton mill shown in the picture – Thomas Taylor’s Victoria Mills in Wigan – during one of Crowe’s trips around the provinces in his capacity as an Inspector of Schools of Art. The verdict of some modern critics is that it is the ancestor of the Northern townscapes of L.S. Lowry, who also painted Wigan scenes, including one of the Wigan Coal & Iron Works which was auctioned in 2008.

The first coal mine had been established at Wigan in 1450, but by the 19th century there were 1,000 pit shafts within 5 miles of the town centre. The town’s cotton and coal industries declined in the 20th centuryand the last working cotton mill closed in 1980.

I did eventually get lunch after a friendly local gave me an excellent recommendation – the Stables Brasserie, located in an 18th Century stable building on Millgate, just yards from the busy centre of the town and the new Grand Arcade Shopping Centre. I had a superb salad Nicoise and a pint of Boddy’s.

After the junction with the Leigh branch, the canal reaches the Wigan flight of 21 locks. This was once a heavily industrialised area, with collieries and ironworks. Today the canal has bequeathed a very pleasant linear park to the town, the adjoining industrial waste ground having been landscaped and the towpath paved to provide an excellent cycle lane that is evidently well-used.

Just before the top lock I was hailed by Alan who asked whether I’d seen any boats coming up the rise (I hadn’t). It turned out that he had worked on the canal before he retired and we chatted for while about how much the area around the locks had changed. Amongst the industrial sites along here were Bridge Colliery and Ince Hall Coal and Cannel Company (cannel being a dull coal that burns with a smoky flame). And beside the top nine locks stretched the Wigan Coal & Iron Works, then one of the largest ironworks in the country. It was a massive operation, employing 10,000 people at the turn of the 20th century. It mined 2 million tons of coal to produce 125,000 tons of iron annually. The skyline here was dominated by 10 blast furnaces, 675 coking ovens and a 339 foot chimney. It must have been an impressive sight on the Wigan skyline at night. All gone now, leaving not a trace.

From the top lock the canal makes a sharp turn left; looking down from here over the town you become aware of the great height climbed through the 21 locks.

Reaching Bridge 59A at New Springs, I decided to call it a day and caught a bus back into town. I travelled out on 9:55 train from Central to Ormskirk, then caught Cumfy Bus 203 to Parbold. Returned by bus to Ormskirk, then Merseyrail home. The bus to Ormskirk stopped at the Arriva depot in Skelmersdale to change drivers. It was there I caught sight of this strange admonition: what bureaucratic mind thought up this?

Back to Liverpool where this ad for British canals is currently on display at the bottom of Leece Street: the end of an everyday getaway.

Next: Wigan to Blackburn

Steps we take

Steps we trace

Into the light of reunion

Paths that cross

will cross again

Paths that cross

will cross again

Speak to me heart

all things renew

hearts will mend

round the bend

Paths that cross

cross again

Paths that cross

will cross again

(Patti Smith, Paths That Cross)

Walking the canal: Halsall to Parbold

I began this leg of the journey at Halsall, where the first sod was ceremonially dug (in November 5, 1770, by the Hon Charles Mordaunt of Halsall Hall) for the commencement of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. A sculpture (‘Halsall Navvy’ by Thompson Dagnall, erected 2006) next to bridge 25 by the Saracen’s Head pub now commemorates this.

I caught the 300 bus to Halsall War Memorial, which stands by the church, a short walk from the canal. The day was warm and sunny, though with a fair amount of clod – but at last it seems the cool, changeable weather we’ve had this May is giving ground to a warm spell. As I set off on the towpath birds were warbling in the reeds on the opposite bank.

On Halsall and the launch of the canal, I found this on the website of the Ormskirk & West Lancashire Numismatic Society:

One of the major constraints on economic development in the eighteenth century was the appalling state of transportation. The roads alternated between mud baths and dust bowls, depending on the season, while navigable rivers were few and far between. Relatively small scale works, such as the Douglas Navigation between Wigan and the Ribble Estuary, had improved matters to some extent, but in 1767 two groups of far-sighted businessmen set up committees, one in Liverpool and one in Leeds, to investigate the construction of a canal to link the growing industrial areas with the coal fields and the major ports of the North East and North West of England. The outcome of their planning was the Leeds and Liverpool Canal Act of 1770, which authorised the construction of the first major canal in Great Britain. The route of this canal passed immediately adjacent to Halsall, and the very first sod turned, in the construction of this industrial miracle, was turned on 5th November 1770 by Colonel Mordaunt of Halsall Hall.

The canal now runs through continuous open countryside, which soon establishes itself as extremely flat and intensively cultivated lowlands. In the large fields alongside there are ranks of cabbage, potatoes and other crops as far as the eye can see.

This was once an area of low lying marshland, much of it below sea level and, consequently, thinly populated. The original course of the River Douglas ran close by, joining the sea near Southport. At some point its course was blocked possibly by giant sand dunes thrown up by a great storm and it found a new, northern mouth in the Ribble estuary, leaving behind the area known today as Martin Mere. This once extended to 15 square miles but in 1787 Thomas Eccleston of Scarisbrick Hall, with the help of John Gilbert, set about draining it for agricultural use (it was Gilbert who, as agent to the Duke of Bridgewater, enlisted James Brindley’s help in constructing Britain’s first major canal). Once drained the mere required vast quantities of manure to raise its fertility for crop production. ‘Night soil’ was shipped in along the canal from the large corturbations of Liverpool and Wigan and off-loaded at a series of small wharfs, some still visible today. Part of the mere remains undrained, a haven for migrating geese.

At Scarisbrick there is an extensive marina providing plenty of mooring places and narrowboats line the canal banks for a mile or so. Scarisbrick (apparently pronounced as ‘Scays-brick’) was, in early times, an area much avoided by travellers. With its vast tracts of poorly drained peat marshes and the huge lake of Martin Mere, it was difficult terrain to cross. Much of the flat land between Southport and Liverpool is, as noted, polder reclaimed from marshes and the lake. The place name itself comes from Old Norse, and literally means ‘the Norseman Skar’s hill-slope’. Scarisbrick appears to have been a village of some size during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

Scarisbrick Hall was the ancestral home of the Scarisbrick family and dates back to the time of King Stephen (1135–1154). The present building, considered to be one of the finest examples of Victorian Gothic architecture in England, was designed by Pugin and completed in 1867. Its most notable feature is the 100-foot tower, which resembles the clock tower of the Houses of Parliament. The building is now occupied by a private day school and public access only allowed once a year. There is a pleasant, wooded section of the canal towpath running alongside the grounds.

Walking on I must have disturbed a lapwing with a nest and chicks in a neighbouring field (they often nest on farmland); she became extremely agitated, circling and calling ‘pee-wit’ as I walked on for several hundred yards. A little further on a pair of orange tip butterflies were active.

At Heatons Bridge I stopped for lunch (splendid roast veg and goat’s cheese baguette with mouth-watering home made chunky chips) and an excellent pint at the pub. Just by the bridge there remains one of the many defensive pillboxes erected as a precaution against invasion during the Second World War.

The next place of significance was Burscough Bridge. The draining of Martin Mere and the building of the canal had a dramatic effect on rural Burscough. The highly productive farmland had always been a major source of work but now even more land was available for cultivation and the growth of Burscough accelerated.

The completion of the canal saw the development of Burscough Bridge into the most important canal town in Lancashire. Burscough became a bustling transport centre, it was a staging post for the packet boats that carried passengers between Liverpool and Wigan, some of whom would transfer to the stage coaches travelling along the turnpike road to Preston and the North.

The traffic on the canal continued to grow in the 19th century. Boats carried coal from the Lancashire coalfields through Burscough on the way to the Liverpool docks and brought commodities for the fledgling industries that sprang up around the canal, such as imported grain for Ainscough’s Flour Mill. Manure was brought from the dray horses and middens of Liverpool and dropped off at the muck quays along the canal, then used to fertilise the reclaimed farmlands and further increase the area’s agricultural output.

A local explained to me that the now-derelict Ainscough’s Flour Mill is a listed building. It was originally owned by H & R Ainscough, who also owned a mill in Parbold and then by Allied Mills until its closure in 1998. The site was bought by Persimmon Homes who plan to convert the mill into apartments, though nothing has happened recently – perhaps because of the credit crunch. After nearly 10 years of disuse, the site is starting to decay, and has suffered some vandalism, but is largely intact. Atmospheric photos of the interior of the mill can be viewed on The View From The North website.

Just after Burscough Bridge the Rufford branch leaves the main canal through an arched bridge dated 1816. A canal settlement, now a conservation area, surrounds the lock and a dry dock: it’s a very attractive corner, with cobbles and old cottages and attractive views over Lathom locks down towards Rufford.

Navigation on the River Douglas pre-dated the Leeds-Liverpool Canal. When the canal was built it replaced the Douglas between Wigan and Burscough. A new cut between the main line and the river at Sollom was built. Later the lock at Sollom was removed and a river lock built at Tarleton. The Rufford Branch in places looks more like river than a man made channel, while the River Douglas has been canalised and is dead straight. Images of the Rufford branch can be viewed on the Towpathtreks site.

About three miles further on is Rufford Old Hall (National Trust), one of Lancashire’s finest 16th-century Tudor buildings. Most famous for its spectacular Great Hall, with carved ‘moveable’ wooden screen and dramatic hammer beam roof, it is also rumoured that a young William Shakespeare performed here for the owner Sir Thomas Hesketh. Another day I’ll visit the Hall and the explore the canal there.

But for now, it was on towards Parbold. A little further on I encountered a sunken boat, a fierce dog and a rather odd place for barbecues in the shape of a fish.

Finally Parbold hill began to come into view, a reminder that I was leaving the Lancashire flatlands and would soon be entering different country.

Along the banks of the canal here is a profusion of Cow Parsley, known also as Queen Anne’s Lace, which seems a more appropriate description of this elegant plant. A Dylan melody goes through my mind:

Purple clover, Queen Anne’s lace

Crimson hair across your face

You can make me cry but you don’t know

Can’t remember what I was thinking of

You might be spoiling me with too much love

You’re gonna make me lonesome when you go

Flowers on the hillside blooming crazy

Crickets talking back and forth in rhyme

Blue river running slow and lazy

I could spend forever with you and never realize the time…

(You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go)