Wilfred Owen died on 4 November 1918 – seven days before the guns fell silent. Yesterday the centenary of his death was marked in the village where he died by a ceremony in which the Last Post was played on a bugle Owen took from a German soldier killed during the battle to cross the nearby Sambre-Oise.

This is a repost of the account of my visit in 2014 to the place where Owen spent his last hours.

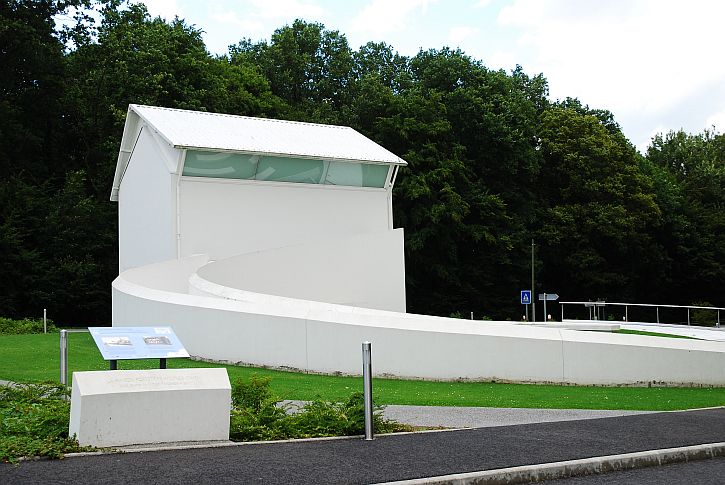

Owen was killed on 4 November 1918, on the Sambre Canal which passes through Ors, a village in a wooded valley some twenty miles to the east of Peronne and the Somme river. Owen and his platoon had spent the previous night in the cellar of a Forester’s House in the wood outside Ors. Owen is pretty much unknown in France, but I had read that the villagers, noticing that a great number of British visitors came looking for Owen’s grave and the exact spot where he had been killed, and asking to visit the cellar of the Forester’s house, had decided to turn the Forester’s House into a monument to the poet, commissioning the British artist Simon Patterson to turn the building into a place for reflection and meditation.

La Maison Forestiere as it appeared before Simon Patterson’s intervention

The house, originally slate-roofed and of red brick with grey shutters, stands on a main road into the nearby town of Le Cateau-Camresis. Patterson decided to preserve the exterior of the house, but to remove the roof and gut the interior. The roof was replaced by a structure that appears normal when viewed from the road, but from other angles takes the form of an open book, with spine uppermost, the ‘pages’ constructed out of glass to admit maximum daylight into the interior.

Most dramatically, Patterson had the entire building rendered in brilliant white, giving it the appearance of a solid sculptural object, and making the house stand out like ‘bleached bone’ (Patterson’s words) against the dark forest beyond. You are reminded, too, of the rows of white gravestones in a British war cemetery.

The brick-lined cellar where Owen and his platoon spent their last night remains untouched, but the interior of the house has been gutted, leaving an open white space, lit from above, and the walls clad with translucent glass onto which are etched drafts of Owen’s poems.

Simon Patterson’s newly-realised Forester’s House

Once I learned of this place I was keen to visit. But I was disappointed to discover that on the day that I would be at Ors, the Forester’s House would be closed. However, the tourist office website indicated that it was sometimes opened at other times for group visits. I emailed to ask whether a group would be visiting on the afternoon I passed by, and whether I could tag along. To my surprise, I received a reply offering to open the House just for me.

I arrived at the agreed time, and was met by a guide from the tourist office at Le Cateau-Cambresis who first of all took me down the steps into the cellar, which remains untouched and is accessed by a curved ramp, alongside which runs the text of Owen’s last letter home to his mother.

Owen’s last letter inscribed on the ramp to the cellar of La Maison Forestiere (photo: magicspello.wordpress.com)

Entering the cellar, you are struck by how crowded it must have been that night when 29 soldiers were holed up here, smoking like chimneys. As you begin to absorb the surrounding a recording begins of Kenneth Branagh reading Owen’s last letter to his mother. It is observant, amusing – and deeply moving.

Owen’s letter was designed to reassure his mother, saying nothing about the impending attack, but instead poking fun at his comrades (‘So thick is the smoke in this cellar that I can hardly see by a candle 12 ins. away, and so thick are the inmates that I can hardly write for pokes, nudges & jolts’) and offering witty pen-portraits of the men (‘a band of friends’) crammed into the small space around him:

To Susan Owen

Thurs. 31 October [1918] 6:15 p.m.[2nd Manchester Regt.]

Dearest Mother,

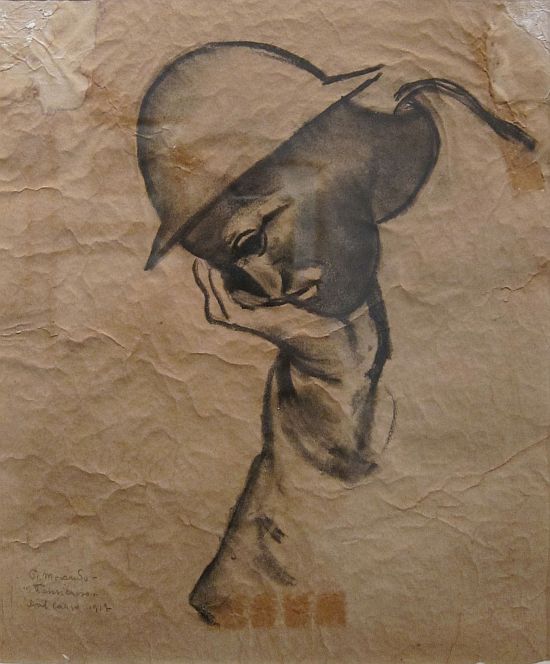

I will call the place from which I’m now writing ‘The Smoky Cellar of the Forester’s House’. I write on the first sheet of the writing pad which came in the parcel yesterday. Luckily the parcel was small, as it reached me just before we moved off to the line. Thus only the paraffin was unwelcome in my pack. My servant & I ate the chocolate in the cold middle of last night, crouched under a draughty Tamboo, roofed with planks. I husband the Malted Milk for tonight, & tomorrow night. The handkerchief & socks are most opportune, as the ground is marshy, & I have a slight cold!

So thick is the smoke in this cellar that I can hardly see by a candle 12 ins. away, and so thick are the inmates that I can hardly write for pokes, nudges & jolts. On my left the Company Commander snores on a bench: other officers repose on wire beds behind me. At my right hand, Kellett, a delightful servant of A Company in The Old Days radiates joy & contentment from pink cheeks and baby eyes. He laughs with a signaller, to whose left ear is glued the Receiver; but whose eyes rolling with gaiety show that he is listening with his right ear to a merry corporal, who appears at this distance away (some three feet) nothing [but] a gleam of white teeth & a wheeze of jokes.

Splashing my hand, an old soldier with a walrus moustache peels & drops potatoes into the pot. By him, Keyes, my cook, chops wood; another feeds the smoke with the damp wood.

It is a great life. I am more oblivious than alas! yourself, dear Mother, of the ghastly glimmering of the guns outside, & the hollow crashing of the shells.

There is no danger down here, or if any, it will be well over before you read these lines.

I hope you are as warm as I am; as serene in your room as I am here; and that you think of me never in bed as resignedly as I think of you always in bed. Of this I am certain you could not be visited by a band of friends half so fine as surround me here.

Ever Wilfred x

Owen’s last letter

From the cellar, my guide led me into the main house where you enter a large, empty space with no photographs or war memorabilia – just Owen’s handwritten draft of ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ reproduced along the walls. The lighting is dimmed and the words of Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ in the poet’s own handwriting is projected onto the facing wall as Kenneth Branagh reads the poem.

The interior of the Forester’s House (photo: Zoe Dawes, www.thequirkytraveller.com)

As a teenager, overwhelmed by the power of ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’, I would never have imagined that one day I would be here, in the place where Owen spent his last hours.

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

The Sambre-Oise canal where Owen and his companions died

Shaking hands with my helpful guide, I left for the place where Owen and his companions met their fate, on the banks of the Sambre-Oise canal just outside the village of Ors. The operation planned for 4 November 1918 seems almost suicidal. In order to cross the canal, the British soldiers had to install a floating bridge under fire from the German machine-guns positioned on the opposite bank.

At 05:45 on 4 November, Owen’s battalion went into action. Accompanying them were men of the Royal Engineers whose task was to assemble, on the canal bank, the sections of the prefabricated floating bridge. The operation had barely started before it was over. A few men managed to cross the canal, but the bridge was destroyed. Hopelessly exposed, a great number of the British soldiers fell under German machine-gun fire. Among them was Wilfred Owen. Futility?

He was twenty-five years old, had published four poems and had written a hundred other unpublished texts half of which had been produced between 1916 and 1918. Two days later, on 8 November, Owen was awarded the Military Cross for his exemplary conduct in an earlier action. On the same day, he was buried in the small square reserved for British military graves in Ors village cemetery. The war ended three days later, and in Shrewsbury, on 11 November, as the bells rang to celebrate the Armistice, Owens’ parents were handed the telegram that all parents feared receiving.

Wilfred Owen’s grave in Ors Communal Cemetery

From the canal, I went to the communal cemetery in the village of Ors, where Owen is buried, along with his companions who also died in the doomed action on the canal. While I stood there, the last line of another of Owen’s great poems came to mind: ‘Let us sleep now …’. ‘Strange Meeting’ was written in the spring or early summer of 1918. Siegfried Sassoon thought it Owen’s passport to immortality:

It seemed that out of battle I escaped

Down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped

Through granites which titanic wars had groined.

Yet also there encumbered sleepers groaned,

Too fast in thought or death to be bestirred.

Then, as I probed them, one sprang up, and stared

With piteous recognition in fixed eyes,

Lifting distressful hands as if to bless.

And by his smile, I knew that sullen hall

By his dead smile I knew we stood in Hell.

With a thousand pains that vision’s face was grained;

Yet no blood reached there from the upper ground,

And no guns thumped, or down the flues made moan.

“Strange friend,” I said, “here is no cause to mourn.”

“None,” said that other, “save the undone years,

The hopelessness. Whatever hope is yours,

Was my life also; I went hunting wild

After the wildest beauty in the world,

Which lies not calm in eyes, or braided hair,

But mocks the steady running of the hour,

And if it grieves, grieves richlier than here.

For of my glee might many men have laughed

And of my weeping something had been left,

Which must die now. I mean the truth untold,

The pity of war, the pity war distilled.

Now men will go content with what we have spoiled,

Or, discontent, boil bloody, and be spilled.

They will be swift with the swiftness of the tigress.

None will break ranks, though nations trek from progress.

Courage was mine, and I had mystery,

Wisdom was mine, and I had mastery:

To miss the march of this retreating world

Into vain citadels that are not walled.

Then, when much blood had clogged their chariot-wheels,

I would go up and wash them from sweet wells,

Even with truths that lie too deep for taint.

I would have poured my spirit without stint

But not through wounds; not on the cess of war.

Foreheads of men have bled where no wounds were.

I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now . . . .”

Ors Communal Cemetery

In The Ghost Road, Pat Barker’s novel which featured historical figures such as Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, alongside fictional characters like Billy Prior, she vividly imagines the disaster at the canal bank:

Bridges laid down, quickly, efficiently, no bunching at the crossings, just the clump of boots on wood, and then they emerged from beneath the shelter of the trees and out into the terrifying openness of the bank. As bare as an eyeball, no cover anywhere, and the machine-gunners on the other side were alive and well. They dropped down, firing to cover the sappers as they struggled to assemble the bridge, but nothing covered them. Bullets fell like rain, puckering the surface of the canal, and the men started to fall. Prior saw the man next to him, a silent, surprised face, no sound, as he twirled and fell, a slash of scarlet like a huge flower bursting open on his chest. Crawling forward, he fired at the bank opposite though he could hardly see it for the clouds of smoke that drifted across. The sappers were still struggling with the bridge, binding pontoon sections together with wire that sparked in their hands as bullets struck it. And still the terrible rain fell. Only two sappers left, and then the Manchesters took over the building of the bridge. Kirk paddled out in a crate to give covering fire, was hit, hit again, this time in the face, went on firing directly at the machine-gunners who crouched in their defended holes only a few yards away. Prior was about to start across the water with ammunition when he was himself hit, though it didn’t feel like a bullet, more like a blow from something big and hard, a truncheon or a cricket bat, only it knocked him off his feet and he fell, one arm trailing over the edge of the canal.

He tried to turn to crawl back beyond the drainage ditches, knowing it was only a matter of time before he was hit again, but the gas was thick here and he couldn’t reach his mask. Banal, simple, repetitive thoughts ran round and round his mind. Balls up. Bloody mad. Oh Christ. There was no pain, more a spreading numbness that left his brain clear. He saw Kirk die. He saw Owen die, his body lifted off the ground by bullets, describing a slow arc in the air as it fell. It seemed to take for ever to fall, and Prior’s consciousness fluttered down with it. He gazed at his reflection in the water, which broke and reformed and broke again as bullets hit the surface and then, gradually, as the numbness spread, he ceased to see it.

[…]

On the edge of the canal the Manchesters lie, eyes still open, limbs not yet decently arranged, for the stretcher-bearers have departed with the last of the wounded, and the dead are left alone. The battle has withdrawn from them; the bridge they succeeded in building was destroyed by a single shell. Further down the canal another and more successful crossing is being attempted, but the cries and shouts come faintly here.

The sun has risen. The first shaft strikes the water and creeps towards them along the bank, discovering here the back of a hand, there the side of a neck, lending a rosy glow to skin from which the blood has fled, and then, finding nothing here that can respond to it, the shaft of light passes over them and begins to probe the distant fields.

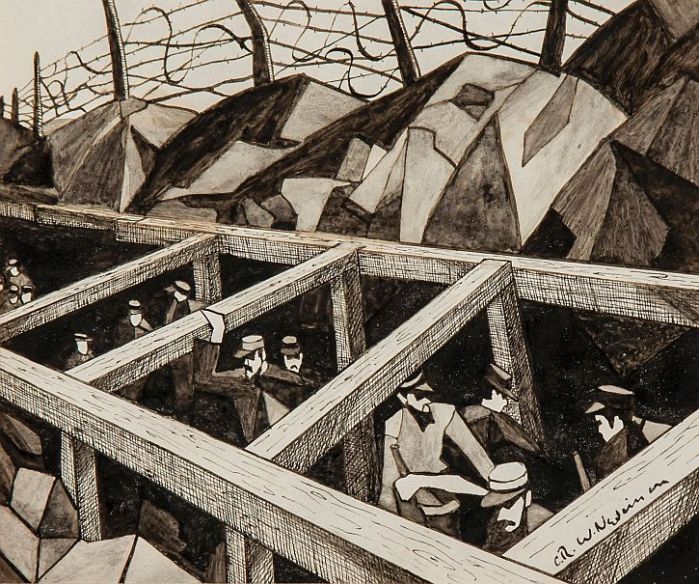

Doomed youth: Wilfred Owen’s regiment

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells,

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs, –

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing down of blinds.

In his new biography of Owen, published this year, Guy Cuthbertson offers this assessment of the poet:

Wilfred Owen remains contradictory: not quite a pacifist, he even hated ‘washy pacifists’; he wrote ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ but he also wanted chivalry; he was the eternal boy who was a grown-up voice in an infantile war; he loved home but was eager to escape it; he was a Christian of a kind, who disliked the Church; conservative and radical, normal and abnormal; the snobbish supporter of the downtrodden; the poet of modernity who was in love with the past; the realist and romantic; he was an innovative and traditional writer who was devoted to poetry and wrote, in the preface to his poems, ‘Above all I am not concerned with Poetry’; he longed for friendship and solitude; he fought gallantly, and urged his men to fight bravely, in a war he had been reluctant to join and then came to oppose bitterly. This is another part of why the man and his poems are so popular – he can appeal to everyone, and remains intriguing.