Yesterday I wrote about the connection between Donna Tartt’s new novel and the 1654 painting by Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch. That set me thinking about why Fabritius had chosen the bird as a subject for a painting, so I thought I’d consult the book I received as a birthday present recently: Birds and People by Mark Cocker.

What I found there proved to be fascinating. In a sense, Carel Fabritius was following a well-established tradition of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance of featuring a goldfinch in paintings, especially images of the Madonna and holy child. What mattered for these artists was not the accuracy of natural history but the bird’s symbolic or allegorical meaning. Cocker reckons that close on 500 paintings in this period included the goldfinch motif. In the case of the Madonna images, the bird often occupied a central place in the composition, perched on Mary’s fingers or nestled in Christ’s hands.

Detail from Taddeo di Bartolo’s ‘Virgin and Child’,14th century

‘Virgin and Child’, Florence, 14th century.

So what was it about the goldfinch that warranted its inclusion in hundreds of paintings? The answer lies in the bird’s plumage and lifestyle, which had produced in the medieval mind powerful symbolic associations. Cocker quotes the scholar Herbert Friedmann who wrote in The Symbolic Goldfinch (1946) of the ‘ceaseless sweep of allegory through men’s minds. They felt and thought and dreamed in allegories’.

Detail from ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ by Hieronymous Bosch, c1510: rampant allegory featuring an outsize goldfinch.

What did the individual feel, then, when they saw an image of a goldfinch? First, there was the bar of gold across the bird’s wings, a colour which, since the ancient Greeks, had been associated with the ability to cure sickness. Then there was the splash of red on the cheeks: as with the robin’s red breast this was a sign to medieval Christians that the bird had acquired blood-coloured feathers while attempting to remove the crown of thorns from while Christ was being crucified.

Finally, not only did thistles have a symbolic association with the crucifixion: thistle seeds are the staple food of the European goldfinch, and thistles were themselves regarded as curative (long credited, for example, as a medicinal ingredient to combat the plague).

John Clare, always observant of bird behaviour, noted the goldfinch’s preference for thistles in his poem, ‘The Redcap’ (an old country name for the bird):

The redcap is a painted bird

and beautiful its feathers are;

In early spring its voice is heard

While searching thistles brown and bare;

It makes a nest of mosses grey

And lines it round with thistle-down;

Five small pale spotted eggs they lay

In places never far from town

(Indeed, goldfinches often come to our bird table here in Liverpool.)

Through its association with thistles, the goldfinch came to be seen as a good-luck charm, ‘warding off contagion and bestowing symbolic health both upon those who viewed it and upon the person who owned it’. Thus the goldfinch came to be a symbol of endurance and, in the case of paintings of the Madonna and child this symbolism was transferred to the Christ child, an allegory of the salvation Christ would bring through his sacrifice.

Carlo Crivelli, ‘Madonna and Child’, 1480

In the Venetian artist Carlo Crivelli’s Madonna and Child, apples and a phallic and misshapen cucumber symbolise sin and a fly evil; they are opposed to the goldfinch, symbol of redemption from the belief that when Christ was crucified, a goldfinch perched on his head and began to extract thorns from the crown that soldiers had placed there.

Detail from Raphael’s ‘Madonna del Cardellino’ (‘Madonna of the Goldfinch’).

In Birds and People, Mark Cocker makes a broader point: that the story of the goldfinch in late medieval art is an indication of how our views of nature have changed. Until relatively recently most people ‘genuinely thought birds existed to fulfil very specific human ends’. He quotes one 18th century author as asserting: ‘Singing birds were undoubtedly designed by the Great Author of Nature on purpose to entertain and delight mankind’.

Which, in a way, brings us back to Fabritius’s goldfinch. Cocker describes the goldfinch as ‘thrice-cursed as a cagebird’: once by its beauty, then by its pleasant song, described by one writer as ‘more expressive of the joy of living than of challenge to rivals’, and finally by its dextrous coordination of bill and feet. In order to feed off thistle heads, the goldfinch has developed the ability to hold down an object with its toes while pulling parts towards them.

Carel Fabritius’s ‘Goldfinch’,1654: ‘thrice-cursed’.

It was precisely these three ‘curses’ that resulted in the predicament of the bird in Fabritius’s painting. Finches like the chaffinch and goldfinch were highly valued as cagebirds for their melodious song, but goldfinches brought something more: they became popular house pets in Holland, kept in captivity attached to a chain and trained to perform the trick of drawing water from a glass placed below the perch by lowering a thimble-sized cup into the glass.

It’s not beyond the bounds of probability that Fabritius, making this painting six years after the United Provinces had gained their independence from Spain, also expected his viewers to read his work as an allegory of freedom chained. In this sense, the painting shares an emotional character with Thomas Hardy’s poem ‘The Caged Goldfinch’:

Within a churchyard, on a recent grave,

I saw a little cage

That jailed a goldfinch. All was silence save

Its hops from stage to stage.

There was inquiry in its wistful eye,

And once it tried to sing;

Of him or her who placed it there, and why,

No one knew anything.

A few decades after Hardy, Osip Mandelstam, in ‘The Cage’ written after Stalin had ordered his arrest and internal exile in Voronezh from 1935 to 1937, summoned the goldfinch to symbolize his yearning for freedom and self-expression and rage at being caged within ‘a hundred bars of lies’:

When the goldfinch like rising dough

suddenly moves, as a heart throbs,

anger peppers its clever cloak

and its nightcap blackens with rage.

The cage is a hundred bars of lies

the perch and little plank are slanderous.

Everything in the world is inside out,

and there is the Salamanca forest

for disobedient, clever birds.

There’s another goldfinch poem by Thomas Hardy – ‘The Blinded Bird’ – that communicates the same sense of rage at freedom denied, ‘enjailed in pitiless wire’:

So zestfully canst thou sing?

And all this indignity,

With God’s consent, on thee!

Blinded ere yet a-wing

By the red-hot needle thou,

I stand and wonder how

So zestfully thou canst sing!

Resenting not such wrong,

Thy grievous pain forgot,

Eternal dark thy lot,

Groping thy whole life long;

After that stab of fire;

Enjailed in pitiless wire;

Resenting not such wrong!

Who hath charity? This bird.

Who suffereth long and is kind,

Is not provoked, though blind

And alive ensepulchred?

Who hopeth, endureth all things?

Who thinketh no evil, but sings?

Who is divine? This bird.

Hardy – who was an antivivisectionist and founder-member of the RSPCA – wrote the poem as a protest against the Flemish practice of Vinkensport in which finches are made to compete for the highest number of bird calls in an hour. In preparation for the contests, birds would be blinded with hot needles in order to reduce visual distractions and encourage them to sing more. In 1920, after a campaign by blind World War I veterans supported by Hardy the practice was banned. Vinkensport – considered part of traditional Flemish culture – continues today, though the birds are now kept in small wooden boxes that let air in but keep distractions out.

Writing this now brings back the memory of standing in a narrow street in Naples this spring, echoing with the roar of motorcycles and the shouts of people passing. Above the din, I heard a bird sing. Opposite, a tenement rose up, balconies draped with the morning’s washing, and on a fourth floor balcony, my eyes found the bird that sang. Some kind of finch, it was trapped in a cage no more than twice its size. I wrote about that experience back in April, and of the poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar that gave Maya Angelou the title of the first volume of her autobiography:

I know why the caged bird sings, ah me,

When his wing is bruised and his bosom sore,—

When he beats his bars and he would be free;

It is not a carol of joy or glee,

But a prayer that he sends from his heart’s deep core,

But a plea, that upward to Heaven he flings —

I know why the caged bird sings!

Leonardo da Vinci, ‘Madonna Litta’, detail

Maybe Hardy had read Leonardo da Vinci’s words on the goldfinch:

The gold-finch is a bird of which it is related that, when it is carried into the presence of a sick person, if the sick man is going to die, the bird turns away its head and never looks at him; but if the sick man is to be saved the bird never loses sight of him but is the cause of curing him of all his sickness.

Like unto this is the love of virtue. It never looks at any vile or base thing, but rather clings always to pure and virtuous things and takes up its abode in a noble heart; as the birds do in green woods on flowery branches. And this Love shows itself more in adversity than in prosperity; as light does, which shines most where the place is darkest.

Ted Hughes celebrated the twitching, thrilling vitality of goldfinches in their free element in ‘The Laburnum Top’:

The Laburnum Top is silent, quite still

in the afternoon yellow September sunlight,

A few leaves yellowing, all its seeds fallen

Till the goldfinch comes, with a twitching chirrup

A suddeness, a startlement,at a branch end

Then sleek as a lizard, and alert and abrupt,

She enters the thickness,and a machine starts up

Of chitterings, and of tremor of wings, and trillings –

The whole tree trembles and thrills

It is the engine of her family.

She stokes it full, then flirts out to a branch-end

Showing her barred face identity mask

Then with eerie delicate whistle-chirrup whisperings

She launches away, towards the infinite

And the laburnum subsides to empty

Simon Armitage, in The Poetry of Birds, wonders why poets have written so many poems about birds. ‘Perhaps at some subconscious, secular level,’ he writes, ‘birds are also our souls’. He continues:

Or more likely, they are our poems. What we find in them we would hope for our work – that sense of soaring otherness. Maybe that’s how poets think of birds: as poems.

Reviewing Donna Tartt’s novel in today’s Guardian, Kamila Shamsie writes that at the conclusion of the book she leads her readers to a place of meaning: in her words, ‘a rainbow edge … where all art exists, and all magic. And … all love.’

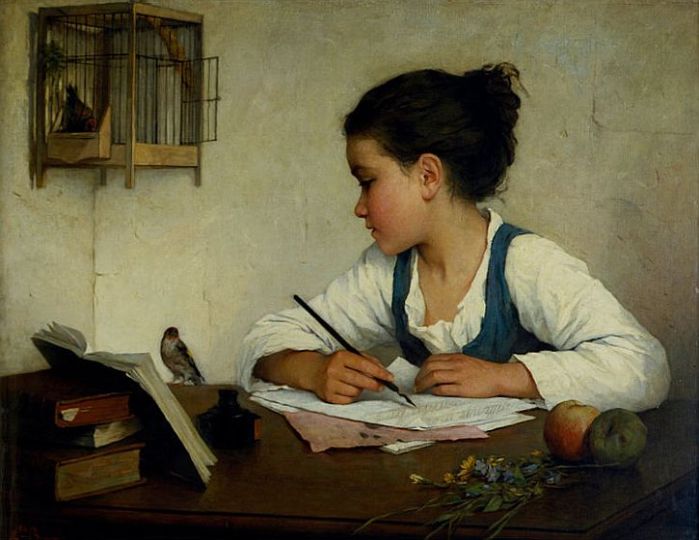

Henriette Browne, ‘A Girl Writing The Pet Goldfinch’, 1870: freedom to fly

Only one adjective to describe this work

It’s also a collective noun

The scholarship is disarming

The article simply charming

Thanks, Andy. May a charm of goldfinches delight you on your way today.

Always astounded by your knowledge and research, so fascinating. One thing that puzzles me is the singular nature of all the goldfinches in these representations…I don’t think I’ve ever seen one alone they always seem to fly in charms. Which probably makes it even more dubious to cage them and makes the freedom reference more poignant. I like what SA has to say about birds and poems.

Well, thank you – but I hope it’s not false modesty to say that much of this is random – as I said at the start of the post, I read a review of Tartt’s new book, then looked up goldfinches in Cocker’s new book that I just happened to get for my birthday a couple of weeks earlier. Topped off with a bit of googling, that’s the genesis of this post, rather than scholarly knowledge or insights already residing in my head! Writing this down now, I must say I like the randomness! A ‘charm’ of goldfinches – you’re right, they are sociable birds, nearly always seen in groups, as are many kinds of birds (though I did see one on its own flitting along the hedge in front of us for a short while on the walk I described recently http://wp.me/poJrg-4jD) which makes their solitary confinement as cagebirds even more unsettling.

I loved this post, thank you. I’m an artist and have been inspired by goldfinches in my work so it’s interesting to read about their cultural associations. The Fabritius painting is a favourite of mine but I hadn’t realised about their other religious and historical associations. If you haven’t come across it already I thought you might enjoy this uplifting poem entitled Goldfinches by the American poet Mary Oliver:

‘In the fields

we let them have-

in the fields

we don’t want yet-

where thistles rise

out of the marshlands of spring, and spring open-

each bud

a settlement of riches-

a coin of reddish fire-

the finches

wait for midsummer,

for the long days,

for the brass heat,

for the seeds to begin to form in the hardening thistles,

dazzling as the teeth of mice,

but black,

filling the face of every flower.

Then they drop from the sky.

A buttery gold,

they swing on the thistles, they gather

the silvery down, they carry it

in their finchy beaks

to the edges of the fields,

to the trees,

as though their minds were on fire

with the flower of one perfect idea-

and there they build their nests

and lay their pale-blue eggs,

every year,

and every year

the hatchlings wake in the swaying branches,

in the silver baskets,

and love the world.

Is it necessary to say any more?

Have you heard them singing in the wind, above the final fields?

Have you ever been so happy in your life?’

Keep up the good work! Kittie

Thank you for reading and commenting, Kittie; but most of all, thanks for the Mary Oliver poem – I should have thought of her, Wild Geese is in the house, but I had forgotten ‘Goldfinches’.

I am looking for a goldfinch singing the original song, send it to my Facebook account, this is Djeghidel mohammed

Very interesting and rich piece Gerry (just bought Mary Oliver as a consequence!) but one small point; the expression ‘thrice-cursed’ comes from my earlier Bird Britannica, not from Birds and People – ever the pedant :-) Mark Cocker

.

Thanks for your generous comment, Mark, and the correction. I have both books and consulted them both when writing this; I’ve obviously blurred the two references. I’ve made an adjustment in the post. I love both books by the way – and always look forward to reading your Country Diary entries in the Guardian (http://bit.ly/1fJvmol). Readers of this blog might also enjoy your blog: http://markcocker.wordpress.com/

Thank you so much for your work on The Goldfinch. I have just finished Donna Tart’s book and had deliberately not looked for the painting until I finished it. This morning I looked for the painting via google and found your blog, I will email it to the members of our book club so they can read it before Thursday’s meeting about Tart’s book. Thank you also for the contributions to your blog above.

Thanks Sally. I hope your reading group find the post informative. I haven’t read Donna Tartt’s book yet – hope to do so soon. Thanks for reading and adding your comment.

What a pleasant surprise to come upon your article on The Goldfinch. I have already e-mailed it to members of our book club which will meet next week. Your research will add another fascinating dimension to our discussion.

Thank you, Lonnie. I hope your group have an illuminating discussion. I have still to read Donna Tartt’s book – it’s one of the big pile awaiting discovery.

There is an book, Friedmann’s The Symbolic Goldfinch which threat in depth the subject

I Live in the North of Scotland and LOVE goldfinches. I feed the birds all the time and have a big bird feeding station, but never have goldfinches, although Friends in the centre of Inverness,only seventeen miles a way have a great many, of these wonderful birds. A few years ago I went to the city of Arezzo and was enchant ed to see a Madonna and Child in The civic house, which is also a gallery.On the uheld Finger of the Christ Child was a beautiful goldfinch. I still remember it. J.Gordon Macintyreyour commentary is excellent.

Thanks for reading, J. I’ve never been to Arezzo (I really must one day). As I’ve mentioned in the post, there are several Maddona and Childs that feature the symbolic goldfinch. There’s one down the road from me in Manchester Art Gallery: http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/virgin-and-child-with-the-goldfinch-204814.

The american goldfinch , the very first bird on my birder life list . It has maintained sentimental meaning to me ever since .

While writing about red admirals, I am struck by way in which Dutch artists in particular appear to have used

them because of the symbolic allusions of red and black, a little as artists seem to have used goldfinches,

In the second image you have labelled ‘Virgin & Child’ , Mary appears to be holding a butterfly in her fingers.

Is this my imagination or could this be a red admiral?

In my books “Butterflies, Messages from Psyche”, “Seeing Butterflies”, and the one I am now working on, I

have concluded that the red admiral (Vanessa atalanta) is a mimic of the goldfinch

Philip Howse

Indeed the Virgin hold a little branch of a tree with two leaves and two red berries

This was absolutely brilliant! Yesterday I was in the National Gallery wondering about the goldfinch in a holy family painting in the Michelangelo/Sebastiano exhibition. It reminded me that years ago I was in Bruges and was fascinated by the symbolism that had to be behind the finch but could find nothing out. Randomly I tried the internet yesterday and your article came up. What a treasure, thank you so much!

Thank you, Liz. I’m pleased you found the post useful.

Reblogged this on 9BlueRoses and commented:

This article appeared right on time

Just like the Goldfinch outside my window…

Right on time, few minutes after a Goldfinch appeared outside my window.

Excellent! Enjoyed the read

The training of Goldfinches is still going on in manyMediterranean countries