Fortuitously, my recent trip to France was bookended by visits to exhibitions that showcased Matisse at the beginning and at the end of his career. Towards the end of the first day I visited the Musee Matisse in his home town of Le Cateau-Cambresis, which houses an astonishing collection of his work, including striking examples from his younger years. Then, on my way back through London, I went to Tate Modern to see Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs, an unparalleled gathering of 130 of the joyous, exuberant works made by Matisse in the last decade of his life: a period which he regarded as a second life, a gift of time. A period in which he turned to painting with scissors.

What is most astonishing about these vibrant works is that they emerge from a period of personal and national darkness. After the invasion of France in May 1940, Matisse, with his daughter Marguerite and his assistant Lydia Delectorskaya, fled from Paris, joining the millions flooding the roads of France seeking shelter from the Nazi invaders. By the end of August he was in Nice, where ‘people gloomily expected Italian Fascist forces to occupy the town at any moment’ (Hilary Spurling, Matisse The Master). He had been experiencing knife-like pains in his gut, soon diagnosed as duodenal cancer. In January 1941, Matisse nearly died after undergoing major surgery. He was in his seventies, and though he recovered he would henceforth be confined to a wheelchair. Matisse, though, felt he had been given a second life. ‘I came within a hair’s breadth of dying,’ he told Swiss art critic Pierre Courthion at the time. ‘Long live joy . . . and french fries!’

For two years, Matisse was too frail to leave his home and studio at the Hotel Regina in the hills of Cimiez above Nice. Moving to the Villa le Reve in Vence in 1941 might seem an enviable billet during wartime, but by 1944 the mountain village was close to the front line of the Allied advance and basic necessities – food, heating, transport – were virtually unobtainable. In April Matisse learned that Marguerite, who had joined the French Resistance, had been imprisoned by the Gestapo. She was interrogated and tortured and Matisse feared that she would be killed. (She managed to escape from the transport taking her to a Nazi death camp in Germany). In the context of such suffering and darkness, the life-affirming movement and colours of the cut-outs – developed by Matisse before and during the war, and then flowering when the war had ended – become an assertion of the human spirit, and an act of defiance.

I’ve dwelt on all this by way of introduction because, wonderful as the Tate’s exhibition is, I feel that both the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue fail to give sufficient emphasis to this context. I recollect that, back in the 1960s and 70s, Matisse was often compared to Picasso (who sat out the war in Paris and was so much more obviously politically engaged), being considered the more effete of the two, living out a life of bohemian luxury in a Mediterranean paradise. Read Hilary Spurling’s biography and it’s clear that nothing could be further from the truth.

There is a painting – not included in this exhibition – that Matisse made in 1940, the year of Nazi invasion, which, for me, seems to go the heart of what Matisse came to express in the cut-outs of the late 1940s and early 1950s. It is ‘The Dream’, an image which had haunted him as he fled with Marguerite and Lydia and the teeming columns of refugees towards the south.

Matisse, ‘The Dream’, 1940

It’s not just the interpretation which you might make of this painting, given the circumstances of its creation; it’s also that we know, from photographic documentation, that he only arrived at this abstract, highly patterned and lyrical image after twelve months, moving from a relatively realistic beginning towards what Doina Lemny called, in the catalogue to a 2012 exhibition, ‘a prime example of Matisse’s ‘metaphysics of decoration’ in which a simple pattern could take on a powerful life of its own and dominate what could have been a simple figure study’. In other words, it’s an example of how Matisse was already pushing towards the decorative distillation of the post-war cut-outs (indeed, had been at least since the studies for the Barnes mural, ‘The Dance’ at the beginning of the 1930s).

What the cut-outs were all about was, as Simon Schama put it, writing in the Financial Times earlier this year:

Matisse believed in the organic connection between decorative form and the irrepressibility of nature. He had committed himself to finding a visual language that would distil and translate the experience of pleasure into images with no loss of sensory intensity; that would, in fact, act as a kind of memory trigger of earthly delight.

Thinking about the decorative characteristics of the cut-outs, it seems we are always drawn back to those formative years of his youth, growing up in Le Cateau-Cambresis and Bohain, immersed in the patterns of the local textiles. In the midst of war, and with his mobility highly restricted, he found some kind of artistic solution there, as Simon Schama observed in the same article:

Even if Matisse, while he was doing the cut-outs for Jazz, didn’t quite know where he was going or what he was doing with them, he certainly did have something to search for. That something was the sign language by which the memory of sensations could be expressed without recourse to any kind of mimetic description – except of the loosest, most analogous kind. He became more and more enamoured of the cut-out, which differed from, say, a symbolic or emblematic visual vocabulary in somehow distilling the essence of something; the experienced sensation of its presence – a nude, a jellyfish, a tobogganist – down to its essentials.

Matisse claimed that he might study whatever it was he had in mind for a cut-out for hours, days, however long it took, before he was ready with the scissors; so that the working procedure became a happy succession of meditative calculation and dynamic physical impulse. Forms of locomotion other than the pedestrian kind of which he was now physically incapable recur in the cut-outs: swimming, of course, but also flight, both of which engendered visual experiences that were, in the best sense, untethered, weightless, and in which light, space, shape, volume and mass all had to be adjusted, or rather were never finally fixed and determined. It was not just the forms that he represented accurately as in gentle, organic, kinetic motion; in that shadowless light, it was the nature of vision itself.

When he finally got going with the scissors, blades accelerating or decelerating with the variable resistance of the stock, he did, indeed, take off: ‘I would say it’s the graphic, linear equivalent of the sensation of flight,’ he said.

You can watch Matisse taking flight graphically in the first room of the Tate’s exhibition, ‘Making the Cut-Outs’, on a short film made by the art collector Adrien Maeght of the artist wielding his scissors. It’s astonishing, the dynamism Matisse exhibits as he cuts with swiftness and absolute sureness, the shapes twisting and falling around him.

The second room, ‘Dancers’, backtracks a bit – to the late 1930s when Matisse produced preparatory sketches and cut-outs of stage designs for for the Ballet Russe in Monte Carlo. Matisse had been fascinated by dance throughout his career, and this work seems to have evolved out of an earlier project – the mural ‘The Dance’ commissioned by the American collector Albert Barnes for his home in Merion, Pennsylvania.

Looking closely at the cut-out designs for the ballet ‘Rouge et Noir’ displayed in this room, you can see how Matisse used cut paper as a way of experimenting: you can see how he layered pieces of the same colour to create the shape he wanted, using pins to attach them to the surface beneath.

Matisse, ‘Two Dancers’, stage curtain design for ballet ‘Rouge et Noir’, 1937-8

Matisse, ‘Two Dancers’, paper cut-out designs for the ballet ‘Rouge et Noir’, 1937-8

Matisse, stage curtain design for the ballet ‘Rouge et Noir’, 1937-8

In 1943, Matisse moved into the Villa le Rêve, a ‘boxlike little house’, according to Hilary Spurling, ‘plain and unassuming’ in the old stone village of Vence in the hills above Nice (Spurling tells a nice story about the first time Picasso came to visit: he found the Villa so plain and unassuming that he initially knocked at the door of a more picturesque place further up the road, and had to be escorted back by a neighbour to the right front gate). Here Matisse began work on Jazz, a book in which he develops the cut paper technique, with more intricate shapes and complicated layering. Jazz is the subject of the third room in the Tate exhibition.

The original idea was for Matisse to illustrate poems, but the flowing hand-written notes he made as he worked on the cut-outs were eventually chosen as the accompanying text instead. I’ve seen the cut-out maquettes for Jazz before, as well as pages from the published book, but at the Tate you can see both versions side by side and compare them.

I’m always a little irritated by the title, chosen by the publisher Tériade, since it has nothing to do with the subject matter of the images (which mainly evoke scenes from the circus or theatre). But Matisse liked the title, with its suggestion of improvisation that connected with the way he worked to create the images. In fact, Jazz was a turning point in the evolution of the cut-outs as art works in their own right: disappointed by the way in which, in the published book, the cut-outs seemed to lose the contrast of different surfaces layered on top of each other, he began to think of them as something more than stepping-stones to printed works.

The cut-out version of ‘Fall of Icarus’ (top) and print version (below)

In the exhibition you can compare the original cut-out version of ‘Fall of Icarus’ with the one included in the book: the designs are quite different. In Jazz, the Icarus figure is black, whilst in the cut-out it is white. In both versions, the figure is surrounded by jagged yellow stars, but each version has different red shape within the chest, and the direction of the figure is reversed.

Matisse worked on Icarus through the summer of 1943, as Allied bombers strafed Nice, and Allied armies had begun fighting their way up Italy towards the Cote d’Azur. In September, German forces heading towards the Italian front entered Nice and Matisse’s basement at the Villa Le Reve was commandeered as a canteen for German soldiers. Air raid sirens broke the silence in Vence, while roads were blocked, trains derailed and bridges dynamited by the local Resistance, trained by Matisse’s eldest son, Jean. Although the yellow splashes around the body of Icarus can be interpreted as stars, it seems likely that in 1943 for Matisse they were exploding shells. Matisse continued to work on Jazz all through the first, bitterly cold winter of food shortages and disruption in Vence. He would have seen RAF bombers pass over Vence, heading towards Nice. One night the sky was lit up after the RAF bombed the gasworks in Cannes. One bomb fell outside the Villa le Reve, battering the front door.

Matisse, ‘Oceania, the Sky’, 1946

Matisse later commented, ‘Only what I created after my illness constitutes my real self: free, liberated.’ Freedom of another kind came – both for the nation, and for Matisse personally – with the liberation of France in summer 1944. The first great triumph of his liberated creativity was Oceania, the subject of room 4. In 1945, Matisse told his daughter that he felt he had gone as far as he could with painting:

Painting seems finished for me now … I’m for decoration – there I can give everything I can – I put into it all the acquisition of my life.

In July 1945, Matisse returned to Paris with Lydia Delectorskaya, travelling by sleeper on the train, and with ambulances laid on at either end. There was a family reunion: Jean had narrowly escaped a Gestapo round-up of the Resistance on the Cote d’Azur, and Marguerite had escaped from the train transporting her to the German concentration camp, while his former wife Amelie, also imprisoned by the Gestapo after Marguerite’s detention, was free, too. Matisse returned to the family apartment on the boulevard Montparnasse, where he began to create a world of cut-out forms on the walls of his studio.

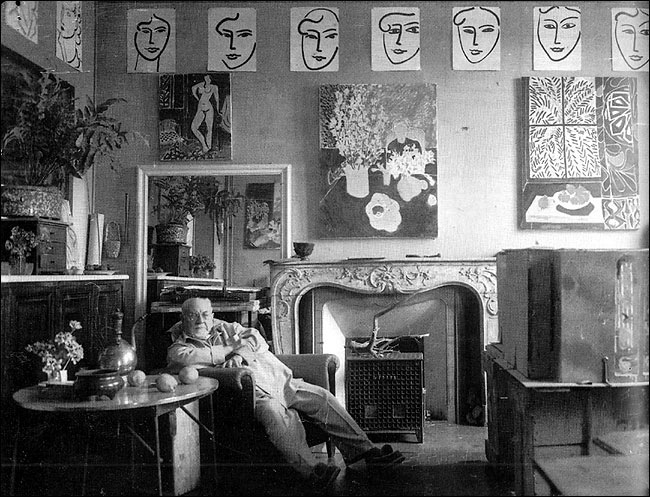

Matisse’s apartment, Boulevard Montparnasse, Paris, October 1946

Lydia Delectorskaya later recalled how it began: in 1946 he had ‘cut out a swallow from a sheet of writing paper… [and] put it up on this wall, also using it to cover up a stain, the sight of which disturbed him’. The swallow was joined by cut-out birds, fish, coral and leaves. His inspiration was the memory of the visit he had made to Tahiti sixteen years before. ‘It’s as though my memory had suddenly taken the place of the outside world’, he explained. ‘There, swimming every day in the lagoon, I took such intense pleasure in contemplating the submarine world.’

When the textile manufacturer Zika Ascher visited, Matisse suggested his Tahitan shapes as patterns. Brought up in a textile-manufacturing town, fabric design was in Matisse’s DNA, cropping up in paintings such as the earlier odelisques. Now, the motifs shaped by his scissors suggested new textile patterns, something he suggested to the textile manufacturer. The result was two large gouache paper cut-outs, mounted on paper and canvas, and realised by Ascher as printed silkscreens on fabric. The Tate display features the two original cut-outs: ‘Oceania, The Sea’ and ‘Oceania, The Sky’. Matisse recalled their inspiration:

From the first, the enchantments of the sky there, the sea, the fish and the coral in the lagoons, plunged me into the inaction of total ecstasy. The local tones of things hadn’t changed, but their effect in the light of the Pacific gave me the same feeling as I had when I looked into a large golden chalice. With my eyes open I absorbed everything as a sponge absorbs liquid. It is only now that these wonders have returned to me, with tenderness and clarity, and have permitted me, with protracted pleasure, to execute these two panels.

This was the first time that Matisse treated his surroundings like a blank canvas which could be used to test out his compositions. Corals, fishes, birds, jellyfishes and seaweeds, were pinned and re-pinned all over the beige walls. All available space was occupied.

Also displayed in this room are examples from an edition of 275 designs on printed silk scarves produced by London-based textile printer Zika Ascher.

Matisse, ‘Écharpe’, produced for Anscher, 1947

The exhibition catalogue begins with a photo essay, offering a glimpse into the three studios where the cut-outs were made – the apartment in Paris, Villa Le Reve in Vence where Matisse lived and worked between 1943 and 1948, and, from 1949 until his death in 1954, the Hotel Regina in Nice. Fortunately Lydia Delectorskaya and many renowned photographers recorded the way in which Matisse used the studio walls as an experimental surface upon which the cut-out shapes could be moved and compositions gradually change and evolve. The next room at the Tate is devoted to the Vence studio.

Matisse in his studio, Vence, May 1948

Matisse studio, Vence, 1948

Before we get to the cut-outs, however, we encounter two paintings – among the last that Matisse ever made – which are displayed here because they show the interior of Matisse’s home and studio at Villa le Rêve. Both paintings are of interest in relation to the cut-outs as they have been built up from elements of design, and rough representation – as if composed from scissored pieces of painted paper. ‘Red Interior, Still Life on a Blue Table, 1947 ‘ is a painting I love for its vivid colours and striking composition with zig-zag black lines. There’s a third painting of this sort from the same period – ‘Interior with an Egyptian Curtain’, 1948 – which is not in the exhibition, but I include here, simply because it’s a favourite, too.

Matisse, Red Interior, Still Life on a Blue Table, 1947

Matisse, ‘Interior with Black Fern’, 1948

Matisse, ‘Interior with an Egyptian Curtain’, 1948

While these paintings make the studio their subject, the studio at Villa Le Reve had now become the physical foundation for the cut-outs, as Matisse composed directly on the wall. One wall of this room is a stunning arrangement of framed cut-outs – a partial reunion of works originally pinned to the studio wall in Vence.

Matisse, framed cut-outs from the Vence studio wall

At one stage, Matisse conceived of this group as one whole composition. The paper shapes were pinned to the wall, allowing him to move pieces around, rotate or invert shapes and try new combinations. Today the shapes have been carefully traced and glued into their final positions, but while Matisse was working the tendrils of his plant forms would gently wave as air passed through the studio. Hilary Spurling, in her biography, writes of Matisse at Vence:

Sitting up in bed cutting shapes out of coloured paper, or playing with the heaps of fallen leaves he collected every autumn and brought home to draw. The toothy, softly-incidsed leaves of oak, the serrated fronds of cineria, the spiky foliage of castor-oil plants and acanthus growing wild along the road outside his gate: all of them had captivated Matisse ever since he moved to Vence.

Here’s an example of how the process worked: this is one of several photos taken of the studio at Vence over a period of time by Michael Sima. It shows, in the bottom left corner, how the composition ‘Amphitrite’ had assumed its final form, composed of shapes which Sima had recorded being been moved from place to place in earlier photos. ‘Amphitrite’ is one of the works displayed in room 5 – a framed cut-out named for the Greek goddess of the sea.

Matisse studio wall, Vence, May 1948

Matisse, Amphitrite, 1948

Room 6 is dedicated to Matisse’s book and periodical designs, including examples of his covers for Verve, an arts magazine published by Tériade, who also commissioned Jazz. In the earliest cover shown here, for Verve’s first issue in 1937, the delicate cut paper strips appear to be a substitute for the painted line. Later designs proclaim their cut paper medium more boldly.

Matisse, cover for Verve, Volume 2, Number 8 (Sept-Nov 1940)

From 1937 to 1975, Tériade (whose real name Stratis Eleftheriades) commissioned artists such as Picasso, Matisse, and Derain to produce works for his prestigious journal. This particular issue of Verve (Volume 2, No. 8, Sept-Nov 1940), was printed just days before the German invasion of Paris. Another interesting book cover here is the one Matisse designed for the first edition of The Decisive Moment by Henri Cartier-Bresson in 1952 (which included the photo, below, of Matisse in his studio at Vence).

Also shown in this room are fragments of film of Matisse and Lydia at work together: Matisse cutting, Lydia pinning, with Matisse pointing and marking where forms should go with a long stick.

Matisse’s design for The Decisive Moment, and Cartier-Bresson’s photo of Matisse

Room 7 of the exhibition is devoted to the work which Matisse himself regarded as the pinnacle of his career – the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence. In 1947 Matisse was approached by Sister Jacques, a nun who had nursed him through his illness four years earlier, to advise on the design of one stained glass window in a new chapel. Soon, however, Matisse was inspired by the whole scheme and embarked upon a commitment that took four years of intensive work, designing not only the stained glass windows and the three large ceramic murals of the chapel’s interior, but also the exterior spire, the wavy blue and white pattern on the roof, the bronze crucifix and candlesticks on the altar, the tabernacle, the wooden confessional door, and the priest’s chasubles, as well as the pond in the garden outside.

In order to understand the relationships between the different elements he was designing, he turned his entire studio – and later his bedroom – into a kind of replica chapel so that he could be immersed in the project at all times. On display here the maquettes for the priests’ robes (an accompanying video shows Matisse working on them), as well as models of the chapel at various stages of its design.

Matisse, maquette for Red Chausable, 1950-2

Matisse developed his designs for the stained-glass windows from cut-outs. The window designs changed several times, and several examples are displayed to illustrate this exploratory process. A highlight of this room is the original maquette design for one of the chapel windows, ‘The Bees’ – a design which he soon discarded but which was later realised for the Henri Matisse nursery school in Le Cateau-Cambresis (where I had seen it, at least from outside on the street, a few days earlier).

Matisse, ‘The Bees’, preliminary maquette for the side windows of the chapel, summer 1948

Another example of discarded design is ‘Celestial Jerusalem’, the first maquette for the apse window of the chapel. It’s a rhythmic grid of irregular cut-out rectangles and polygons, dominated by reds, yellow and orange.

Matisse, ‘Celestial Jerusalem’,1948

By 1949, Matisse had rejected this in favour of a second design, ‘Pale Blue Window’, in which swaying seaweed or leaf-like forms are reminiscent of the ‘Oceania’ wall hangings. This design had to be discarded, too, as Matisse had overlooked the lead braces needed to hold the window together. Matisse’s third design – ‘Tree of Life’ was the one which eventually took its place in the chapel’s apse window. It is stunning, and certainly the best of the three, probably because, as Hilary Spurling states, it ‘contains no red, a change of key that brought an extraordinary clarity, serenity and stillness to the music of the chapel’. See it in situ here. At the Tate, a maquette of the design was on show.

Picasso was scornful of Matisse spending so much effort on a chapel, suggesting he would have made better use of time decorating a fruit market. But what is really interesting about Matisse’s designs for the chapel is their almost total avoidance of traditional religious iconography. The result is a space that can be appreciated by anyone – of any faith, or none. Alastair Sooke writes:

When the chapel was completed, Matisse was old and infirm. Long after the doctors who had operated on him in 1941 expected him to pass away, he was still persevering in the face of physical adversity, at times driven by nothing more than a cussed, bloody-minded instinct to keep on making art. ‘Do I believe in God?’ he wrote in Jazz. ‘Yes, when I am working’.

For Sooke the chapel is ‘a sanctuary of tranquillity’: ‘constructing it required ‘immense effort’, as the artist said, but the finished effect was effortless. This I believe, is the essence of Matisse’. Noting the subtle allusions to Islamic art in the chapel’s design, Sooke continues:

It is almost as if Matisse, inspired by memories of Moorish Spain and North Africa, wanted his chapel to transcend religious faith. It didn’t matter what you believed in, or even if you were an out-and-out atheist: the chapel would still exert its soothing, calming influence upon your mind. […]

As Matisse said during an interview in 1950: ‘I believe my role is to provide calm. Because I myself have need of peace.’ I find that very moving and noble indeed.

Matisse, ‘Pale Blue Window’, 1949

Matisse, The Tree of Life (maquette), 1949

By room 8 the size of the works on display begins to reveal how, as Matisse’s skill and experience with the cut-out technique increased, so did the scale of his work. You’re immediately faced with a stunning wall on which two of the most celebrated cut-outs – ‘Zulma’ and ‘Creole Dancer’ – are positioned side by side. ‘Zulma’ is a significant work because, for the first time, Matisse creates a sense of depth in a cut-out composition, receding space suggested by the angled table on which the figure leans. Made and exhibited when Matisse was eighty, ‘Zulma’ was widely praised for its radical approach, hailed as the most youthful work in an exhibition of work by other, far younger artists.

‘Creole Dancer’ is based on sketches he made of the French prima ballerina Yvette Chauvire when she visited him in his studio at Villa Le Reve and danced for him. Matisse’s assistant Jacqueline Duheme later recalled watching the dance;

When we look at dancers, it always seems so aerial and light, but when they stand just three metres away, you realise all the work it requires. You hear the noise of the feet and pointed toes. Matisse was very interested in this. He would say, ‘You see, Jacqueline, everything is an effort. Even when one looks so light, it is still hard. Everything is hard!

Yet ‘Creole Dancer’ was made in a single day using left over pieces of painted paper. In his excellent short Penguin book, Henri Matisse: A Second Life, Alastair Sooke makes the observation:

It is telling that Matisse found within her performance an analogy for his own thoughts about making art. … Matisse could have been talking about his chapel at Vence, which required so much effort, but ended up looking so light.

Matisse was very fond of ‘Creole Dancer’, and would not part with it, explaining to his son Pierre: ‘I think that it has exceptional quality, and it is both agreeable and useful for me to keep it by me. […] I am not certain that I can do any more work of that quality, in no matter what medium, and for that reason I want to hold on to it’.

Matisse, ‘Zulma’, 1950 and ‘Creole Dancer’, 1950

Also displayed in this room is ‘Tree’ from December 1951, done in ink, gouache and charcoal on paper, mounted on canvas. It’s on loan from MoMa.

Matisse, ‘Tree’, 1951

Then there’s ‘Chinese Fish’, a maquette for a stained glass window installed at Villa Natasha in St Jean Cap Ferrat, the home of Teriade, publisher of Jazz and Verve. The Matisse museum at Le Cateau- Cambresis has recreated the villa’s dining room where the stained glass window was installed.

Matisse’s ‘Chinese Fish’ window: a recreation of the Teriade room at Musee Matisse, Le Cateau-Cambresis (photo: https://magicspello.wordpress.com/)

Matisse, ‘Chinese Fish’, maquette, 1951

Matisse, ‘Mimosa’, 1949: design for carpet (realised in 1951)

Matisse, ‘Snow Flowers’, 1951 (watercolour and gouache on cut and pasted papers)

Matisse, ‘Vegetables’, c.1951

‘The Thousand and One Nights’, a long panel composed of various leaf and other shapes bordered top and bottom by green and red hearts, was entirely new to me. It’s 12 foot by five foot, and was created in June 1950 when the artist was 81 and confined to his bed.

Unable to sleep, but still driven to create, Matisse had quite a bit in common with Scheherazade, the narrator of the Persian classic Arabian Nights. Scheherazade saves her own life from a vengeful king by enthralling him with a story that she always interrupts at a moment of suspense just after dawn, ensuring her survival through 1,001 nights. Like the original that inspired it, ‘The Thousand and One Nights’ is a work ‘rich in fantastical imagery and symbolism’ created during many sleepless, difficult hours. The composition – with its magic lamps, dancing plant forms and hearts – evokes the passage of time through the night, with the first panel, a lantern with smoke seeping out of its spout, denoting dusk. The text pasted across the upper right-hand corner reads, ‘…as dawn approached she discreetly fell silent.’

Matisse, ‘The Thousand and One Nights’, 1950

I keep thinking that there can be nothing to surpass what I’ve already seen, but then, in room 9, I find all the ‘Blue Nudes’ together in one room! From Basel, the Pompidou, Centre Musee d’Orsay and Nice: they are all here!

The ‘Blue Nudes’ are perhaps the most striking example of what Matisse himself called ‘cutting directly into colour’. Here scissors both create the outline of the figure and carve contours into it. The paper’s flatness coexists with a sense of the figures’ intertwined limbs. These works reveal Matisse’s cutting to be a means of drawing and sculpting at the same time. Matisse’s assistant Lydia Delectorskya aptly described his work on a cut-out figure in these terms: ‘modelling it like a clay sculpture: sometimes adding, sometimes removing’. Looking at them I was reminded of the four monumental sculptures of a woman’s back which Matisse worked on from 1909 to 1930 that I had seen a few days previously in the Musee Matisse at Le Cateau-Cambresis.

Matisse, ‘Blue Nude IV’, 1952

See together, numbers 2 and 3 are the most expressive. ‘Blue Nude IV’ was, in fact, the first of the series (but also the last to be completed). Matisse struggled over ‘Blue Nude IV’ for two weeks, and on the composition you can see traces of his struggle: faint lines of charcoal drawing and layered separate small pieces of blue paper. By contrast, the other Blue Nudes were cut ‘in a single movement’ from one blue-painted sheet. Lydia recalled: ‘Each on a different day, they had been cut with … one stroke of the scissors in ten minutes or fifteen maximum’.

Matisse, Blue Nudes I-IV, spring 1952

Room 10 is dominated by ‘The Parakeet and the Mermaid’, one of the largest cut-outs Matisse ever made. The two creatures of the title are nestled among fruit and his characteristic algae-like leaf forms. The composition is the product of a good deal of experimentation. Matisse tried out different shapes – including a Blue Nude – where the mermaid is today. As it blossomed across his studio walls, Matisse described the work as his garden. Too frail to leave his house, here was a way of bringing the outdoors inside.

On the left-hand side of ‘The Parakeet and the Mermaid’ is the bird of the title. Matisse explained:

You see, as I am obliged to remain often in bed because of the state of my health, I have made a little garden all around me where I can walk. There are leaves, fruits, a bird. Restrained movement, calming.

On the right is the mermaid, ‘wriggly, slick and lubricious’ in Alastair Sooke’s words. It’s a figure that recalls the dancer in ‘Flowing Hair’ that he had pinned to the studio wall at the same time. Matisse recalled in evocative terms the memories of Tahiti that were the inspiration for ‘The Parakeet and the Mermaid’:

The leaves of the high coconut palms, blown back by the trade winds, made a silky sound. This sound of the leaves could be heard along with the orchestral roar of the sea waves, waves that broke over the reefs surrounding the island. I used to bathe in the lagoon. I swam around the brilliant corals emphasised by the sharp black accents of sea cucumbers. I would plunge my head into the water, transparent above the absinthe bottom of the lagoon, my eyes wide open … and then suddenly I would lift my head above the water and gaze t the luminous whole.

Matisse, ‘The Parakeet and the Mermaid’, 1952 (photo Sue Lowry)

All the works in this room share a white background, regarded by Matisse not as a neutral setting for the design, but as an active part of the work; he felt that the contrast between white and the coloured cut paper gave his compositions a ‘rare and intangible quality’. Hilary Spurling tells how visitors to Matisse’s studio in the Hotel Regina in the early 1950s were hard put to find words to describe it: ‘ a gigantic white bedroom like no other on earth’, said one. ‘A fantastic laboratory’, said another.

Matisse explained to newcomers that the whole apartment had once been so filled with greenery and birds that it made him feel like he was inside a forest. Now he had got rid of his plants. […] Instead he filled his white walls with cut-paper leaves, flowers, fronds and fruit from imaginary forests. Blue and white figures – acrobats, dancers, swimmers – looped and plunged into synthetic seas. Diffused and disembodied colour seemed to emanate not so much from any particular motif or composition as from the space itself.

Matisse, ‘Blue Nude with Green Stockings’, 1952

Matisse, ‘Woman with Monkeys’, 1952

Matisse studio, Hotel Regina, Nice, September 1952

During the last three years of his life Matisse made several ambitious large-scale works. By now cut-outs in progress covered most available walls of his home in the Hotel Regina in Cimiez. Often, he would work on several of them simultaneously, with cut shapes sometimes migrating across compositions. What had attracted him to cut-outs originally – the ability to try out and rearrange compositions – grew in potential as he pushed the technique further.

Hotel Regina, September 1952: ‘Large Decoration with Masks’ (left), ‘The Flowing Hair’ above door

‘Large Decoration with Masks’ was made as a design for a ceramic panel. Its pattern of natural forms suggests that Matisse was drawing on his memories of Moorish mosaics seen forty years previously in Morocco. ‘It is such a consolation for me to have achieved this at the end of my life,’ he wrote to his son.

Around the same time as he was considering this symmetrical and regularly patterned composition, Matisse was also using cut paper in quite different ways, in the bold physicality of ‘Acrobats’, for example. Here, when his own movement was so severely limited, Matisse chose to depict a body stretching with flexibility and motion, emphasising the curve of backs and the stretch of arms.

Matisse, ‘Large Decoration with Masks’, 1953

Matisse, ‘Acrobats’,1952′ and Woman with Amphora and Pomegranates’, 1953

Room 12 is dominated by ‘The Snail’ which lives permanently in Tate Modern. It is displayed alongside ‘Memory of Oceania’: Matisse initially imagined the pair as part of one huge composition, with ‘Large Decoration with Masks’ at its centre. With ‘The Snail’, he pushed the cut-out technique further away from representation than ever before, though he described it as ‘abstraction rooted in reality’. The rotating paper shapes radiate out in a spiral, echoing a snail’s shell. Working on an earlier snail, he talked about becoming ‘aware of an unfolding’. Unusually, the individual shapes are not carefully scissored, but roughly cut and sometimes even torn.

Matisse, ‘The Snail’ (photo Sue Lowry)

With ‘Memory of Oceania’ Matisse once again drew on happy recollections of his 1930 trip to Tahiti, bringing the lagoon into his studio. While working on it, he remembered the light of the Pacific as ‘a deep golden goblet into which you look’.

Matisse, ‘Memory of Oceania’, 1953

‘Ivy in Flower’ is another full-scale maquette of coloured paper, watercolour, pencil, and brown paper tape on paper mounted on canvas that he created in 1953 for a stained glass window commissioned by the wife of an American businessman, Albert Lasker, for his mausoleum. Mrs Lasker rejected it, after seeing only a photograph, on the grounds that was ‘all yellow’. Having devoted much time to the project, Matisse was furious, feeling that he living on borrowed time and had wasted some of his precious ‘second life’.

Matisse, ‘Ivy in Flower’, 1953 being manoeuvred in its home at Dallas Museum of Art

The penultimate room of the exhibition is another stunner, displaying two tremendous works, ‘Acanthuses’ and ‘The Sheaf’. ‘Acanthuses’ is spare, minimal, its shapes limited to the three primary colours yellow, red and blue and their composite hues green (from yellow and blue) and orange (from yellow and red), and once again surrounded by a vast white space. Matisse had sketched the composition on paper using a long stick with a piece of charcoal attached to the end.

For all his growing confidence in the cut-out medium, Matisse’s process was still one of trial and revision. Conservation analysis has found more than a thousand tiny pin holes in the coloured shapes of Acanthuses, suggesting many alterations before the composition attained its final form.

Matisse, ‘Acanthuses’ at the Foundation Beyeler, Basel during conservation (photo: Mark Niedermann)

‘The Sheaf ‘, with its leaf patterns in blue, green, orange, red and black was a design for a ceramic panel that was finally accepted by the couple who commissioned it for their Los Angeles home. Matisse had already proposed several designs, including ‘Large Decoration with Masks’, which they had rejected. Matisse was undaunted by their response and embarked on alternative compositions with enthusiasm, reflecting the extraordinary creative energy of his final years.

Matisse, The Sheaf, 1953 (photo Sue Lowry)

The final room of the Tate’s exhibition contains just one work – ‘Christmas Eve’, a stained glass window on loan from MoMA. Here we can compare his cut-out model with the resulting stained glass, commissioned for the Time-Life Building in New York. Like his windows for the Vence Chapel, Christmas Eve conveys the spirit of religious expression without explicitly addressing religious subject matter or using religious iconography.

Matisse once said of his designs for Jazz, ‘I cut out these gouache sheets the way you cut glass: only here they’re organised to reflect light, whereas in a stained-glass window they have to be arranged differently because light shines through them.’

Matisse, ‘Christmas Eve’, photo: Panoptic Art (http://panopticart.tumblr.com/)

The exhibition was a magnificent experience: though I had seen many of the works in different settings over the years, there will never again in my lifetime be the opportunity to see so many of these glorious, life-affirming works in one place. Reviewing the exhibition for the Independent, Zoe Pilger wrote:

The cut-outs are ecstatic though controlled. Matisse described the process of making these staggeringly bright, large-scale works as ‘painting with scissors.’ Rather than painting onto canvas, he was cutting ‘in’ – making incisions. There is no sense of surgery, however. There is little sense of conquering, violating, penetrating – all those metaphors of creativity associated with the ‘modern masters’ of the 20 century. Instead, these works are exultant; they make you feel happy, high, vital, which is what the artist intended.

Matisse, stained glass window, Pocantico church, New York State

Matisse’s last work – his final cut-out – is not here. It was the design for a stained-glass window commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller for the Union Church of Pocantico Hills, New York State, in memory of his mother. On 1 November Matisse wrote to say that his design of ivy in flower was finished and ready for production. The same day he suffered a mini-stroke. His doctor later wrote: ‘His worn-out heart slowly ceased to beat. It took three days.’

His daughter Marguerite and his assistant Lydia stayed at his bedside. On the second day Lydia came to his bedside with her hair newly washed and wound in a towel turban. Matisse asked for his drawing things and made four quick sketches of her with a ballpoint pen. Holding the final sketch out at arm’s length he pronounced, ‘It will do’.

Matisse died the next day, 3 November 1954, at four o’clock in the afternoon in the studio at Cimiez, with his daughter and Lydia at his side. In the final words of her biography, Hilary Spurling writes:

He is buried in the cemetery at Cimiez, in a plot of ground on the hillside overlooking Nice, with no monument except a plain stone slab carved by his son Jean, beneath a fig tree and an olive to which time and chance have added a wild bay tree fifty years after his death.

You can watch Alastair Sooke’s Culture Show appreciation of Matisse and the cut-outs on YouTube:

See also

- Henri Matisse: celebrated in his home town

- Matisse: his last resting place and resurrection

- A summer of Matisse: Palm trees, palms, and the rhythms of jazz

- A summer of Matisse: the colour of music

- Matisse in Nice: through an open window

- The Art Books of Henri Matisse

- The Chapelle du Rosaire by Matisse (April 2008)

- A visit to the Matisse Museum in Nice (April 2008)

- How Henri Matisse created his masterpiece: Alastair Sooke on the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence

Thanks for writing this excellent post! I did not get to see the exhibition at Tate when I was in London earlier this year and was rather disappointed. At least I got to ‘walk’ through it through your post :)

Wow! Thank You Very Much! :-) I so wanted to go to this exhibition, but after reports of how crowded it was decided not to. Viewing from a wheelchair is difficult, and not everyone is helpful about letting me get in front of them (even though I would not obscure their view). I did go to the Matisse and Fabrics (can’t remember proper title) some years ago, and people were wonderful and kind, plus chatted in a friendly way too. Perhaps I should have made the effort this time too. But “Life Keeps Happening”, which makes it difficult to book things – at least I’ve been able to read your very interesting and comprehensive view of the exhibition, for which I’d like to thank you again. And I was loath to leave my current nesting spot in Bwlchtocyn to go to London. Will be there soon enough (in October), more than one trip to London in a year is more than I’m happy making (recovery time from journeys and the excitement on them is excessive).

Terrific post! Thank you.

Beautiful. One to return to more than once.