Who would have thought that the dark grey shapes in a pack of dog biscuits are derived from willow ash, a product which aids digestion and reduces flatulence? This was just one of the fascinating insights offered by Fiona Stafford, Professor of Literature at Somerville College Oxford, in a series of Radio 3 essays last week entitled ‘The Meaning of Trees’.

In her talks, Fiona Stafford explored the cultural, economic and social significance of five different trees – yew, ash, oak, willow and sycamore – outlining the symbolism and importance of each tree in the past and their changing fortunes and reputations. She revealed how some trees are yielding significant new medical and the environmental benefits.

So, for example, in her first essay Stafford noted that the Yew has been labelled ‘the death tree’ because of its toxicity: every part of the tree is poisonous, and it bleeds a remarkably blood-red sap. Yet today these ancient trees have the most modern of uses – as part of the fight against cancer.

Yews are renowned for their astonishing longevity, and are most often associated with churchyards. Yet, as Stafford pointed out, many ancient yews pre-date the churchyards where they stand. They mark ancient, sacred sites on which Christianity, as the new religion, built. Yews continued to be planted in churchyards where their toxic leaves would not endanger grazing livestock.

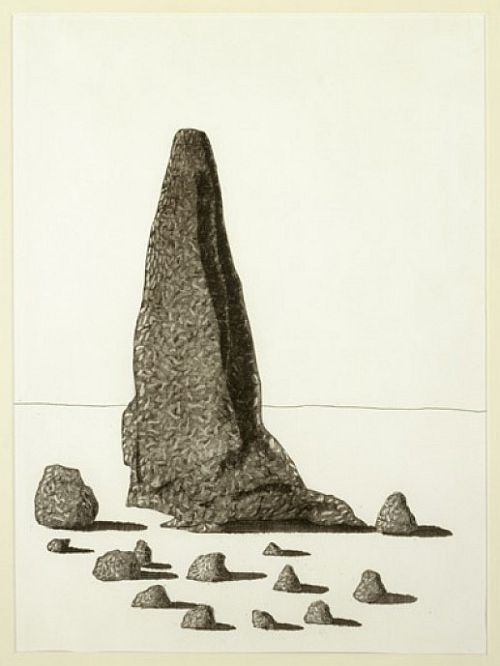

The Fortingall Yew in Perthshire (above) is Europe’s oldest tree at over 3,000 years old, and was already a veteran when the Romans arrived. Stafford spoke of how the astonishing longevity of the yew and its evergreen branches have suggested comforting thoughts of everlasting life to mourners in churchyards, while the dark, dense boughs offer privacy and stillness.

A distinctive feature of yews is that they don’t conform to any standard, but evolve into many diverse shapes and forms. They were tamed and trimmed in Renaissance mazes and parterres, and over the centuries some have grown into fantastical forms, as we saw for ourselves some years back at Powis castle in Wales, where the terrace is bounded by a 30 foot yew hedge and huge strange shaped ‘tumps’ formed over the centuries by the annual round of clipping and shaping. (below).

But, said Fiona Stafford, the yew also gained a reputation as ‘the death tree’, due to its toxicity – every part of the tree is poisonous. Shakespeare described the tree as ‘double fatal’ – its boughs poisonous, while arrows crafted from yew also brought death. The yew, that bleeds red with remarkably blood-red sap if its bark is cut, has triggered deep fears: yews are there in ghost stories and gothic horror and loom through the gathering darkness of Gray’s Elegy. In Tennyson’s In Memoriam, the yew is both resented for still being alive when his friend is dead, but also celebrated for its longevity:

Old Yew, which graspest at the stones

That name the under-lying dead,

Thy fibres net the dreamless head,

Thy roots are wrapt about the bones.

The seasons bring the flower again,

And bring the firstling to the flock;

And in the dusk of thee, the clock

Beats out the little lives of men.

O not for thee the glow, the bloom,

Who changest not in any gale,

Nor branding summer suns avail

To touch thy thousand years of gloom:

And gazing on thee, sullen tree,

Sick for thy stubborn hardihood,

I seem to fail from out my blood

And grow incorporate into thee.

With its blood-red berries and leaves resistant to winter’s trials, yews were a symbol of everlasting life, the oldest living things in Europe. The longevity of the yew was illustrated by Fiona Stafford when she told how, at Fountains Abbey in the 12th century, the yews were already so large that the monks could live in them while the abbey was being built. Some living yews are older than Stonehenge or the pyramids. Trees that were seedlings 3000 years ago were already vast by time Romans arrived.

The idea of the yew symbolizing everlasting life might now be reinforced, Stafford argued, by the tree’s new role in the fight against cancer. In the 1960s, scientists discovered that taxol, derived from the bark of the yew, could be used in chemotherapy. A newer formulation is now used to treat patients with lung, ovarian, breast and other forms of cancer.

But there’s a downside for the tree: stripping bark from the trees kills them, and as a consequence the Himalayan Yew is now an endangered species. Careful harvesting of yew needles would produce the same benefits and be more sustainable but, being slower, yield lower profits. ‘The impulse to fell’, Stafford concluded, ‘has a humane as well as a profit dimension’. This is not the first time that human exploitation has threatened the yew: Stafford described the medieval decimation of the European yew for arrows.

But, Stafford concluded, it is not the yew’s dark façade or poisonous needles but its very long life that is troubling: the tree will survive into a future when we’ve all been forgotten. If all that’s left of the people who planted some of our more venerable trees are their broken beakers, she queried, what will remain of those in today’s garden centres trundling their potted yews to the checkout? Their purchase may be their most long-lasting legacy.

Although we don’t yet know what else the yew has hidden away, one day we might. What is the meaning of the yew? Stafford concluded: it’s much too early to say.

In her second essay, Fiona Stafford tackled the tree which has suddenly hit the headlines. The Ash is now threatened by the arrival in Britain of the fungus called Chalara fraxinea which causes ash dieback. But, said Stafford, the Ash has survived since the birth of humanity and has met mortal threats before. Despite many different near fatal epidemics over the centuries, delicate ash trees have survived for millennia.

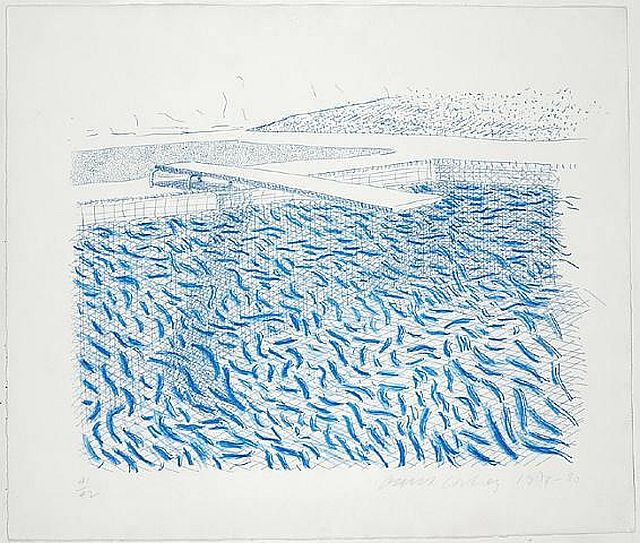

As evidence of the significance of the Ash in our culture and for the British landscape, Stafford cited David Hockney’s recent Royal Academy show in which ash trees peopled the fields of the Yorkshire Wolds (above) – a return, she said, to the great tradition of British landscape painting. [For a discussion of the prospects for the trees painted by Hockney, see Will Ash Dieback affect Woldgate Hockney Trees?]

Stafford cited John Constable as an example of another English painter in love with the graceful form of the ash. The tree figures in paintings such as Cornfield and Flatford Mill, and in drawings which Constable made of a favourite ash on Hampstead Heath (below).

In the summer of 1823 Constable rented a house in Hampstead. He admired trees and made many studies of them, always noting their specific shapes and varying foliage. In this drawing – Study of an ash tree – inscribed and dated ‘Hampstead June 21 1823. longest day. 9 o clock evening – he defined the particularities of an ash tree at a given moment and at a specific location, combining intense feeling for the tree with accurate observation of the tree trunk, branches and leaves, as well as capturing the air between the leaves and the wind passing through.

Stafford told how Constable described the tree as having died of a broken heart after a notice warning against vagrancy was nailed unceremoniously to the trunk. ‘The tree seemed to have felt the disgrace’, he lamented, for almost at once some of its top branches withered, and within a year or so when the entire tree became paralysed, and ‘the beautiful creature was cut down to a stump’. His friend and biographer C.R. Leslie wrote of Constable’s love of trees, and of the ash in particular:

I have seen him admire a fine tree with an ecstasy of delight like that with which he would catch up a beautiful child in his arms. The ash was his favourite, and all who are acquainted with his pictures cannot fail to have observed how frequently it is introduced as a near object, and how beautifully its distinguishing peculiarities are marked.

It was a favourite tree, too, of Edward Thomas. In Ash Grove, written in 1916, war has concentrated his mind on a vision of England, at ‘a moment’, in Stafford’s words, ‘when the past, unwilling to die, floods the present with joyful sunlight, and an ordinary clump of trees becomes magnified into something extraordinary’. Thomas also evokes his Welsh ancestry in the poem’s recollection of a girl singing the old Welsh folk song ‘The Ash Grove’:

Half of the grove stood dead, and those that yet lived made

Little more than the dead ones made of shade.

If they led to a house, long before they had seen its fall:

But they welcomed me; I was glad without cause and delayed.

Scarce a hundred paces under the trees was the interval –

Paces each sweeter than the sweetest miles – but nothing at all,

Not even the spirits of memory and fear with restless wing,

Could climb down in to molest me over the wall

That I passed through at either end without noticing.

And now an ash grove far from those hills can bring

The same tranquillity in which I wander a ghost

With a ghostly gladness, as if I heard a girl sing

The song of the Ash Grove soft as love uncrossed,

And then in a crowd or in distance it were lost,

But the moment unveiled something unwilling to die

And I had what I most desired, without search or desert or cost.

Stafford discussed the many cultural associations of the ash, including its health benefits. Pliny noted that its leaves were considered an effective antidote to snake bites, while later generations valued the ash as a cure for obesity and gout, and its bark a tonic for arthritis, while warts could be eradicated by a prick from a pin that had been inserted into the bark.

The ash was an integral part of life, giving its name to innumerable places, and wherever people lived and worked the ash tree was a constant companion. Its reputation as a friend to man rested not only on its physical beauty or medicinal value, but also the versatility of ash wood. Its toughness and elasticity lent itself to the manufacture of wagon wheels, skis, walking sticks, bentwood chairs, as well as cricket stumps and billiard cues. Stafford told how, during the Second World War, when metal was scarce, ash was used in construction of the de Havilland Mosquito, a wooden bomber. Ash was also the wood used for the Morris Traveller wood frame, and is still used today in the construction of Morgan sports cars.

Given the ubiquity of the tree, it was not surprising, Stafford suggested, that the ancient people of northern Europe thought the entire world depended on the ash. In Nordic myth, even human beings were thought to derive from piece of ash driftwood the Norse gods found on the shore. Ask was the first human, created by the gods from that piece of ash; in Old Norse askr means ‘ash tree’.

Our history with the ash is long. In Norse mythology, the World Tree Yggdrasil was an ash tree, with two wells feeding its roots – wisdom and destiny. Stafford told how Norse mythology also ‘foresaw the end of the known world when Yggdrassil would shake and crack, the land would be engulfed by ocean, and the old gods overthrown. They knew that the great ash tree would not last forever.’ But, asked Stafford, can we protect the ash now that it fights off a new threat to its existence?

She pointed out that ashes not renowned for their longevity, living only a couple of hundred years at most. But coppiced they will continue to send up shoots from the dead heartwood, and their abundant seeds – or keys – also lead to rapid propagation. The ash is tolerant of almost any soil, and – until now – has been one of most familiar trees in Britain. It is hard to imagine an ash-less Britain, but, with Chalara fraxinea now alarmingly set on sweeping through British Isles, Stafford concluded, ‘the future of the ash tree is far less assured than its past’.

Fiona Stafford began her essay on the Oak in that most English of locations – the bar of the Royal Oak. Here, in a pub bearing the third most popular pub name in England, you are likely to be surrounded by oak – the bar and tables made of oak, and the beer’s flavour and colour deepened in oak barrels. Oak, she said, is such an integral part of our culture we scarcely notice it.

Sturdy, stalwart, stubborn: the oak is a symbol of enduring strength that has inspired poets, composers and writers for millennia. But not just in England. The oak has been chosen as the national tree of many other countries, too, including Estonia, France, Germany, Moldova, Romania, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the United States, and Wales.

Civilisations have been built from oak, as its hard wood has been felled for houses, halls and cities, its timber turned into trading ships and navies. Other woods are as strong, but few are as long-lasting as oak. Some oak trees, observed Stafford, served as ale houses, some were gospel oaks under which parishioners gathered to hear readings from the Bible. She might have added that the spreading branches of others served as shelter for local council meetings – such as the Allerton Oak (above) in Liverpool’s Calderstones Park, now over a thousand years old, beneath which the sittings of the local ‘Hundred court’ were held.

When war threatened, oak proved crucial for national defence, oak wood being unique for its hardness and toughness and thus ideal for shipbuilding. But the oak’s value also led to its decimation since a large naval vessal required some 2000 oaks, and replanting was a slow affair, with replacement trees only reaching maturity after two or three hundred years.

In one of the most fascinating parts of her talk, Fiona Stafford explained that the English are not alone in identifying the oak as a symbolic tree. The oak is the emblem of Derry in Northern Ireland, originally known in Gaelic as Doire, meaning oak. The Irish County Kildare derives its name from the town of Kildare which originally in Irish was Cill Dara meaning the Church of the Oak. The oak is a national symbol for the people of the Basque Country, as well as being used as a symbol by a number of political parties, including the Conservative Party. As Stafford observed:

The outspread arms of the oak offered a congenial symbol and make the complicated story of its political exploitation a telling example of how different notions of nationhood can be cultivated, felled, or replanted. If the same tree can inspire both conservative admiration for inheritance and radical enthusiasm for equal rights, as well as unionist pride in inclusiveness and separatist determination for independence, it’s difficult to be too absolute about what the oak’s real meaning might be.

Sacred to the Celts and the Ancient Greeks, the oak tree has been central in British culture, present in place-names and national songs; yet it is also the national tree of dozens of countries. It was once the most common European tree, but then the huge demand for oak timber led to a steep decline. Commenting on the famous Major Oak of Sherwood Forest (above), Stafford wondered:

‘Is the Major Oak in Sherwood Forest, its collapsing branches so carefully cradled by poles and wires, a heartening image of a caring community, or does it provoke less cheering ideas of a people clinging to memories of a great, but increasingly vanishing past?’

But then, she concluded, perhaps the impulse to interpret trees as anything but trees is one to handle with care.

The poor soul sat singing by a sycamore tree.

Sing all a green willow:

Her hand on her bosom, her head on her knee,

Sing willow, willow, willow:

The fresh streams ran by her, and murmur’d her moans;

Sing willow, willow, willow

– Othello, Act IV, Scene 3

Fiona Stafford began her essay on the Willow by observing that for poets and dramatists it has long been the tree of loss, abandoned lovers, and broken hearts. Shakespeare had Desdemona singing her willow song on the last night of her life and Ophelia sinking into the brook by the willow:

There is a willow grows askant a brook,

That shows his hoar leaves in the glassy stream;

There with fantastic garlands did she come: [….]

There, on the pendent boughs her coronet weeds

Clambering to hang, an envious sliver broke;

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook.

Something about this tree, it seems, makes everyone want to weep – but the problem, as Stafford pointed out, is that many such references to the willow in folk songs (and in Shakespeare) pre-date the arrival of the Weeping Willow in Britain in the 18th century. It’s claimed that the Weeping Willow was first introduced by the poet Alexander Pope who received a basket of figs from Smyrna in Turkey. Noticing that one of the twigs making up the basket was still alive, he planted it in his garden in Twickenham where it grew into the willow tree from which, it’s claimed, all others have been propagated. By early 19th century the Weeping Willow was widely recognised, not least due to the willow pattern pottery designed by ceramics artist Thomas Minton (who also invented the legend which the design illustrates).

So Shakespeare’s willow, and the willow of old folk songs, must have belonged to one of the many indigenous varieties – white willow, crack willow, bay willow, etc, etc. The easiest of trees to propagate, the pliable branches of the quick-growing willow have been used for basket-weaving, wicker-work, cradle-making, thatching or fencing. Osiers, the shrubby willows (above), are the best for basket-making, with stems so strong and pliable that they can be woven into wickerwork without snapping.

A dramatic symbol of the past importance of the willow for local economies is, as Fiona Stafford noted, Serena Delahaye’s giant willow man (above), a prominent landmark beside the M5 northbound between junction 24 and 23, near Bridgwater in Somerset. The sculpture stands 40 feet high and is made of locally grown black maul willow, woven around a steel skeletal frame. The current figure is the second on the site. The original was destroyed by fire in 2001. We have seen it from a speeding car on our way to Cornwall: a celebration of the traditional local industry of the Somerset Levels. Fiona Stafford offered a reminder that in Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees, Roger Deakin devoted a chapter to the willow growers of the Somerset Levels.

The willow’s fortunes have fluctuated over the centuries, according to the practical needs of the time. In times of war its lightness and flexibility meant that it was used to make artificial limbs, while willow charcoal was used to make gunpowder. Doctors also used the charcoal for dressing wounds, and willow was used as a remedy for fever and rheumatism. Pain relief derived from the willow’s salicylic acid, which yielded aspirin. Eventually this led to the development of salacin, an anti-inflammatory agent that is produced from willow bark and which is closely related in chemical composition to aspirin. Willow charcoal is not only the best for sketching, but has also been used to manufacture medicinal biscuits aimed at aiding digestion – thus the grey dog biscuits mentioned at the start.

The willow’s flammability (which led to its use in making gunpowder) mean that it is now being developed for biomass. In Scandinavia, willow wood chip is already replacing oil as a cleaner fuel for domestic heating, as well as for industrial purposes. Willows offer a reliable, carbon-neutral source of heat – they grow so fast, absorbing carbon dioxide, that they can be harvested very frequently, producing cheap and easily-renewable supplies of fuel. Willow-fuelled power stations being planned. Willows could also form part of an effective defence against flooding, with the long roots thriving in moist soil and helping to stabilise river banks.

So, synonymous with Englishness, having furnished the raw material for cricket bats since the 1780s (when a new variety of white willow was identified in Suffolk, providing an especially resilient, wide-grained wood) the willow is now at the cutting edge of medicinal and biomass development.

Fiona Stafford finished her survey of the willow’s meaning, by noting that when Claude Monet was trying to achieve ‘the ideal of an endless whole, unlimited by shores and horizons’, he turned again and again to the lily pond at Giverny. ‘It was’, said Stafford, ‘as if he could paint with plants, filling the pool with water lilies, surrounding it with weeping willows. In the paintings, planes and surfaces dissolve as the multi-petalled flowers float on reflections of trees, and the vertical fronds of the willows make waves more visible than water’.

‘Monet’s willows’, concluded Stafford, ‘are perhaps the ultimate image of the ever-shifting willow: a tree so adaptable that it can be taken for water, sky, earth or sun. And what might the willow be saying? So much depends on the circumstances’.

In massy foliage of a sunny green

The splendid sycamore adorns the spring,

Adding rich beauties to the varied scene,

That Nature’s breathing arts alone can bring.

Hark! how the insects hum around, and sing,

Like happy Ariels, hid from heedless view—

And merry bees, that feed, with eager wing,

On the broad leaves, glazed o’er with honey dew.

The fairy Sunshine gently flickers through

Upon the grass, and buttercups below;

And in the foliage Winds their sports renew,

Waving a shade romantic to and fro,

That o’er the mind in sweet disorder flings

A flitting dream of Beauty’s fading things.

– John Clare, ‘The Sycamore’

There’s a tall sycamore that stands in a neighbouring garden and in summer, from mid-afternoon, casts our lawn and patio into deep shade. It has annoyed me through the thirty-odd years that we lived here, and I have longed for it to be cut down.

In her final essay, Fiona Stafford challenged the popular image of the Sycamore as an unwanted, problematic weed, the cause of ‘the wrong kind of leaves on the line’ that disrupt British railways each year; the tree with too many leaves, too much sap, and too many seedlings.

Instead, Stafford focussed on the benefits of the sycamore. As John Clare observed in his poem, with its dense foliage and sweet sap the tree is a haven for insects and sipping bees. Clare, said Stafford, was ahead of his time in understanding this. The sycamore is now valued, too, as a haven for all kinds of birds.

Sycamores annoy because of their resilience. Sycamore seeds, with their propellers, spread far and wide on the wind and take root anywhere. They are hardy trees, loved by urban councils for their resistance to salt and tolerance of the pollution and harsh environment of city streets. Consequently, the sycamore has become the most common tree in British cities.

In Britain, as Stafford noted, attitudes to the sycamore have always been ambivalent. Already, in 1664, John Evelyn was asserting that the sycamore should be banished from gardens and avenues because of its reputation for shade, and the honeydew-coated leaves which, after their fall, ‘turn to a mucilage … and putrefie with the first moisture of the season [and so] contaminate and marr our Walks’. Many continue to hold such views, and see it as a weed which should be eradicated. As Richard Mabey observes in his magnificent book Weeds:

The mythology stacked against it is formidable. It’s a true weed, invasive and loutish. Its myriad seedlings swamp the ground and out-compete native trees. Its large and ungainly leaves litter the earth, then slowly rot to a slithery mulch. They are ‘the wrong sort of leaves’ that famously cause trains to skid to a halt every autumn.

But as both Stafford and Mabey observe, though widely regarded as a non-native species, the sycamore was introduced to Britain in Tudor times while, ironically, more recent arrivals, such as 19th century exotic imports, have been highly prized.

Yet, for Stafford, there is ‘something inspirational about the ordinariness of the sycamore’. Seen as an ordinary tree, the sycamore has never been valued for its rich timber, even though its wood is as strong as oak, and more easily dyed. The sycamore, she suggested, stands for extraordinary possibilities latent in the commonplace. A familiar feature of almost every rural area, their thick foliage offers shade to sheep and cattle, shelter to solitary farmhouses, and has inspired poets as varied as John Clare and W B Yeats. In Tintern Abbey, Wordsworth expressed his profound delight in the prospect of the Wye valley seen from beneath a ‘dark sycamore’, referring to its sun-blocker foliage.

Stafford finished by recalling that the oldest sycamore in England is probably the Tolpuddle tree, beneath which gathered, in 1834, the Dorset agricultural labourers who became pioneers of the trade union movement. Barred from church halls or other indoor spaces, they gathered beneath the sycamore to stand up for their rights and resist their long hours and low wages.

The Tolpuddle sycamore

53.410777

-2.977838