Sitting in a darkening room yesterday as evening came on, I sensed snowflakes falling beyond the window. Torn by a western wind and rain that had fallen throughout the day, the falling shards of ghostly white were the petals of the magnolia tree that stands in our front garden, planted by us thirty years ago. Every year since, its trunk has thickened and its branches have spread; and every spring before coming into leaf it has put forth its creamy-white, goblet-shaped flowers in growing profusion. This year it reached full maturity, putting on a display that has lit up our window and the entire street. Seeing this annual unfolding fills me with great happiness. Planting this tree three decades ago strikes me now as being one of the most satisfying and valuable things I have ever done. Continue reading “To plant a tree: a love song to a magnolia planted thirty years ago”

Tag: trees

‘In times like these, it’s necessary to talk about trees’

What times are these, in which

A conversation about trees is almost a crime

For in doing so we maintain our silence about so much wrongdoing!– Bertolt Brecht, ‘To Those Who Follow in Our Wake‘, 1939

During the Christmas break, while reading Fiona Stafford’s engrossing The Long, Long Life of Trees, I was also hearing the news from Sheffield, where residents were outraged when private contractors, hired by the city council under a cost-cutting PFI, began cutting down hundreds of trees lining city streets. Now, luminaries such as Jarvis Cocker and Chris Packham are fronting a campaign to save Sheffield’s roadside trees. In the Guardian the other day, Patrick Barkham was writing about the pensioners being prosecuted under anti-trade union legislation for peacefully opposing the felling of trees in their street. His report included this striking statement by furious local and one-time member of Pulp, Richard Hawley:

This hasn’t got anything to do with politics. I’m a lifelong dyed-in-the-wool Labour voter. I was on picket lines with my dad. I don’t view protesting against the unnecessary wastage of trees as all of a sudden I’ve become fucking middle class. I know right from wrong and chopping down shit that helps you breathe is evidently wrong. We’re not talking about left or right. We’re talking about the body. It boils down to something really simple. Do you like breathing? It’s quite good. It’s called being alive. What we exhale they inhale and what we inhale they exhale. The end.

Continue reading “‘In times like these, it’s necessary to talk about trees’”

The Oak Tree: Nature’s Greatest Survivor

A quick shout-out for Oak Tree: Nature’s Greatest Survivor, shown on BBC 4 this week (and available for another 25 days on iPlayer) – a 90-minute documentary detailing a year-long study of a single 400-year-old oak in Oxfordshire. The film was presented by entomologist George McGavin, who promised that ‘You’ll never look at an oak tree the same way again.’ Too true: McGavin took us on an engrossing tour of the oak (literally so, by climbing the tree, and even sleeping in its uppermost branches!), guiding us through its biology and cultural significance. Continue reading “The Oak Tree: Nature’s Greatest Survivor”

The Birthday Tree

There was a cherry tree in the front garden of the house in Cheshire where I grew up. Every year in spring, when the delicate white blossom would appear suddenly, as if snow had fallen overnight, I would sense that brighter, longer days were on the way. It later succumbed to poisoning from a poorly sealed-off gas main. Continue reading “The Birthday Tree”

Oxford B&B

We spent 24 hours in Oxford last week – there primarily to see Cezanne and the Modern, the current exhibition at the Ashmolean. Somehow, I’ve reached retirement age without ever having been to Oxford before, so we spent time strolling through the streets of the town and ambling along the shaded path that lies between the Cherwell and Christ Church Meadow.

I was quite taken aback by how much Oxford conformed to what I had assumed was a clichéd image I had of the town: you know – young people punting lazily along the Cherwell, drinks in hand; bicycles everywhere, left leaning against walls and railings; the honey-coloured Cotswold limestone of the buildings. Two of the most memorable places we encountered on our meanderings were the Botanic Garden (above) and the Bodleian Library.

Poppies in Oxford Botanic Garden

The University of Oxford’s Botanic Garden is Britain’s oldest, founded almost 400 years ago, when the first Earl of Danby donated £5000 to start a ‘physic garden’ to grow plants that would support medical practice. From the beginning the garden was intended to be, in Danby’s words, ‘for the glorification of God and the furtherance of learning’. Danby might have been motivated to appease the almighty by having, thirty years earlier at the age of 21, murdered a man in a long-standing feud between families.

A site for the garden was chosen on the banks of the River Cherwell at the north-east corner of Christ Church Meadow. The land belonging to Magdalen College, part of it having been a Jewish cemetery until the Jews were expelled from Oxford (and the rest of England) in 1290.

The garden, established for ‘the furtherance of learning’, continues to support scientific enquiry and understanding, but is also a place for taking aesthetic pleasure in nature, or for quiet contemplation. Undergraduates studying biological sciences at the university visit the garden to learn about many aspects of plant biology, while thousands of school children visit the garden each year as part of the university’s schools education programme.

Strolling around the rectangular ‘family beds’ where plants are grouped according to their botanical family, geographical origin or uses, we occasionally came across signs that described the investigations currently going on in a particular section.

The garden is home to more than 5000 plant species – on less than five acres of land, this makes it, according to the guide we were given, one of the most biodiverse places on Earth. In addition to colourful flowerbeds, there are sections where herbs and vegetables are grown, and – dispersed throughout the garden – some very interesting and beautiful trees. One tree survives from the original 16th century planting – an English yew, a species, as a label informs, that today is the source of drugs used to treat breast and ovarian cancer.

The blossom of the Tulip tree

There is a Gingko, a Monkey Puzzle, and a Tulip tree with beautiful blossoms that look like tulips, though the plants are not related. Most dramatic was the towering Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), a tree known only in the fossil record until several living ones were discovered in China in the 1940s. This one was planted in 1948, so is my age but a little taller.

The Dawn Redwood

Then there is the Black Pine. I love pines, and this one reminded me especially of one of my favourite Cezanne paintings, ‘The Great Pine’. But this tree has literary, rather than artistic associations. Indeed, the garden is rich in literary associations: Charles Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll, would bring the children of Henry Liddell, Dean of Christ Church (including Alice), for picnics in the garden. In John Tenniel’s original illustrations for Alice in Wonderland the garden’s water lily house can be seen in the background of one of the plates illustrating the Queen of Heart’s Croquet Ground.

Alice in the Queen of Hearts’ croquet ground: inspired by the Botanic Garden

The Black Pine, brought here as a tiny seed in 1795, was the favourite tree of Oxford professor and author, JRR Tolkien, who often spent hours in the garden sitting under this tree.

The Pinus Negra in the Botanic Garden

The tree is also a favourite of another Oxford-based author, Philip Pullman; he so loves this tree that he has Lyra, the heroine of His Dark Materials, sit under it tree at the conclusion of the trilogy. In his story, a bench beneath its spreading branches is one of the locations where the parallel worlds inhabited by the protagonists, Lyra Belacqua and Will Parry. In the last chapter of the trilogy, both promise to sit on the bench for an hour at noon on Midsummer’s day every year so that perhaps they may feel each other’s presence next to one another in their own worlds.

The bench is now the subject of pilgrimage, and the names of Lyra and Will have been carved on the backrest. Such is the resonance of this place that the University has added to its website a podcast in which the author shares his passion for the Botanic Garden and reads from the end of the His Dark Materials trilogy where Lyra sits beneath the pine and dreams of the time when the Republic of Heaven will be established:

The Master had given Lyra her own key to the garden door, so she could come and go as she pleased. Later that night, just as the porter was locking the lodge, she and Pantalaimon slipped out and made their way through the dark streets, hearing a’r the bells of Oxford chiming midnight. Once they were in the Botanic Garden, Pan ran away over the grass chasing a mouse towards the wall, and then let it go and sprang up into the huge pine tree nearby. […]

She sat on the bench and waited for Pan to come to her. He liked to surprise her, but she usually managed to see him before he reached her, and there was his shadowy form, following along beside the river-bank. She looked the other way and pretended she hadn’t seen him, and then seized him suddenly when he leapt on to the bench. […]

Pantalaimon murmured, ‘That thing that Will said. . .”

‘When?’

‘On the beach, just before you tried the alethiometer. He said there wasn’t any elsewhere. It was what his father had told you. But there was something else.”

“I remember. He meant the kingdom was over, the kingdom of heaven, it was all finished. We shouldn’t live as if it mattered more than this life in this world, because where we are is always the most important place.”

“He said we had to build something. . .”

“That’s why we needed our full life, Pan. We would have gone with Will and Kirjava, wouldn’t we.”

“Yes. Of course! And they would have come with us.

“But -”

“But then we wouldn’t have been able to build it. No one could, if they put them first. We have to be all those difficult things like cheerful and kind and curious and brave and patient, and we’ve got to study and think, and work hard, all of us, in all our different worlds, and then we’ll build. . .”

Her hands were resting on his glossy fur. Somewhere in the garden a nightingale was singing, and a little breeze touched her hair and stirred the leaves overhead. All the different bells of the city chimed, once each, this one high, that one low, some close by, others further off, one cracked and peevish.

another grave and sonorous, but agreeing in all their different voices on what the time was, even if some of them got to it a little more slowly than others. In that other Oxford where she and Will had kissed goodbye, the bells would be chiming too, and a nightingale would be singing, and a little breeze would be stirring the leaves in the Botanic Garden.

“And then what?” said her daemon sleepily. “Build what?”

“The republic of heaven,” said Lyra.

Gallery: Oxford Botanic Garden

Earlier we had drifted into the quadrangles that enclose the Bodleian Library, the main research library of the University of Oxford, and one of the oldest libraries in Europe. In Britain it is second in size to the British Library, containing over 11 million items. In its current form the library has a continuous history dating back to 1602, though its roots can be traced back even further. The first purpose-built library known to have existed in Oxford – a small collection of chained books – was founded in the fourteenth century by Thomas Cobham, Bishop of Worcester.

The Divinity School, built between 1427 and 1483, and attached to the Bodleian Library

Thomas Bodley was the son of a Protestant merchant family from Exeter who had studied under Calvin in Geneva – a Protestant exile in the reign of Queen Mary- before returning to England when Elizabeth came to the throne to study at Merton College) In 1598 he wrote to the Vice Chancellor of the University offering to support the development of the small existing library.

The library expanded rapidly, with the Schools Quadrangle – where we had entered – being added between 1613 and 1619. Doorways leading off the quadrangle are labelled with the names of various disciplines and I was interested to note the entrance to the School of Natural Philosophy. Only a week before I’d heard Melvyn Bragg’s panel on In Our Time discuss the work of the pioneering scientist Robert Boyle – one of the first to conduct rigorous experiments to lay the foundations of modern chemistry.

Doorway to the Schola Moralis Philosophiae (School of Moral Philosophy) at the Bodleian Library

Except that Boyle – as a member of the panel pointed out – wasn’t a scientist, and would not have understood the term. He was a natural philosopher, the term scientist only coming into use in the mid-19th century. As an interesting feature in yesterday’s Guardian explained, the word was coined in 1840 by the Reverend William Whewell in his book The Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences, which contained a 70-page section on the Language of Science:

In it he discusses how the new words of science should be constructed. He then coins the universally accepted term physicist, remarking that the existing term physician cannot be used in that sense. He then moves on to the larger concept. ‘We need very much a name to describe a cultivator of science in general. I should incline to call him a scientist.’ The word that scientist replaced was philosopher. An account of this coinage in Word Study, a newsletter published by Merriam-Webster in 1948, noted: ‘Few deliberately invented words have gained such wide currency, and many people will be surprised to learn that it is just over a century old.’

The Radcliffe Camera

Leaving the quadrangle, we came face to face with a circular building constructed from the local honey-coloured limestone. This was the Radcliffe Camera, designed by James Gibbs in neo-classical style and built between 1737 and 1749 to house the Radcliffe Science Library. Known as the Radcliffe Camera (camera, meaning ‘room’ in Latin), it was taken over by the Bodleian in 1860, as the library grew short of space.

Gallery: Bodleian Library

On a warm afternoon, we strolled the sun-dappled path alongside the Cherwell, as students punted past us in celebratory mood. Where the Cherwell meets the Thames we sat and watched teams of rowers as they practised on the Thames, the shouts of their cox’s splitting the air. Later we enjoyed a drink at the waterside pub by Folly Bridge, The Head of the River. Then over the river to The Folly restaurant for a delicious meal on the terrace as the sun set on a balmy evening.

Gallery: Cherwell and Thames

The meaning of trees: the way we see the world

Is the rowan tree still there in the garden of the house where I grew up? The thought occurred to me as I listened to the second of five talks by Fiona Stafford on The Meaning of Trees, broadcast last week in BBC Radio 3’s Essay strand (and available as a podcast download). Stafford had begun by explaining the Rowan’s popularity as a tree for suburban gardens – it’s easy to grow, is good on all kinds of soil, is low maintenance, and doesn’t grow too large.

For gardeners the tree has several benefits. It’s a tree for all seasons – a kaleidoscope of changing colours throughout the year, from creamy spring blossom and pistachio summer green to autumn’s bright scarlet berries. It’s popular with bird-lovers because it’s a favourite of blackbirds and thrushes. The result is that rowans found in suburban streets and gardens all over Britain.

Yet this is a tree that first flourished in wild upland areas. And, as Fiona Stafford suggested, it’s long experienced something of an identity crisis, bearing a confusion of names at various times. ‘Rowan’ reflects the Viking influence in Scotland, since the word derives from the Old Norse reynir,meaning red. The tree’s popular name Mountain Ash is a double misnomer: although it had its origins in highland areas, the tree is now just as common in the south. Moreover, it is not related to the Ash (the confusion arose because of the similarity between the pinnate leaves of the two species). Then there’s the Old English name of cwic-beám, which survives in the name quickbeam (where ‘quick’ = life). Fiona Stafford considered various explanations as to why, from Anglo-Saxon times, the tree should have acquired its association with life. Perhaps it derived from its use as charm for infertile land, or from the therapeutic value of the berries (they make an excellent gargle for sore throats, apparently), or maybe it was something to do with the quivering leaves.

So the rowan comes in many guises: white ash, mountain ash, quickbeam, whispering tree, witchwood. As Fiona Stafford explained, this shifting identity suits a tree that is at once safe and suburban and a tree sacred to antiquity, renowned for its protective powers. She spoke of how the rowan figures prominently in Irish, Scottish and Scandinavian traditions, its berries considered the food of the gods. It features in old Irish poems, and has many associations with magic and witches. Its old Celtic name is ‘fid na ndruad‘ which means wizard’s tree. It also crops up in poems by Seamus Heaney, such as ‘Song’:

A rowan like a lipsticked girl.

Between the by-road and the main road

Alder trees at a wet and dripping distance

Stand off among the rushes.

There are the mud-flowers of dialect

And the immortelles of perfect pitch

And that moment when the bird sings very close

To the music of what happens.

This is the second series on The Meaning of Trees presented by Fiona Stafford, Professor of Literature at Somerville College Oxford. Like the first, this one explored the symbolism, economic importance, and cultural significance of five trees common in the UK. While the first series considered the yew, ash, oak, willow and sycamore, in the second Stafford discussed the rowan, pine, poplar, hawthorn and apple.

Gustav Klimt, Pine Forest, 1901

Before the discussing rowan, now flourishing in suburban gardens, Fiona Stafford had begun her series with another domesticated species – one that has found a place in almost every room of the house – and in providing key ingredients of many household products. Stafford was talking about the pine. She began:

The year is 1975. The summer is scorching, and people are starting to strip.

She’s talking about the new wave in furniture:

In the kitchen we have pine tables, dressers, cupboards; in the bedroom pine headboards, wardrobes and drawers; in the bathroom there’s more pine for the cabinets, towel rails, shelves and brush-holders.

Everyone, Stafford exclaimed, is going pine mad. How true! This was the era of Habitat and local artisans retailing reclaimed and freshly-stripped pine (or, with effort, you could do it yourself). We, too – a young couple setting up home in our first flat – were part of this pine revival that was, in Stafford’s words, ‘a reaction against the polythene, plastic and polyester space age’. Instead of lino and Formica that mimicked wood, we wanted the real thing.

A native of Scotland, economically the pine is the world’s most important tree. There are not only the obvious uses in the furniture, building and paper industries, but also its medicinal properties in treating bronchitis and pneumonia for millennia and its resin, used to manufacture glues, gums, waxes, solvents and fragrances. It’s the ultimate versatile tree, providing the base oil for emulsion paint, turpentine for cleaning brushes, pitch for waterproofing ships’ timbers – and licorice allsorts.

The drowned pine and oak forest of Borth

The pine has been a British native tree for over 4000 years, with dark pine forests entering legends and fairytales. Fiona Stafford told how, after the ferocious February storms, a prehistoric drowned forest of pine and oak from between 4,500 and 6,000 years ago was revealed when thousands of tons of sand were stripped from beaches in Cardigan Bay. At Borth the remains were exposed of a forest that once stretched for miles before climate change and rising sea levels buried it under layers of peat, sand and saltwater. The trees echo the local legend of a lost kingdom, Cantre’r Gwaelod, drowned beneath the waves.

Wind-tossed pines on the Mediterranean coast at Giens, near Hyeres

Stafford spoke of the pine’s time-old ‘tendency to help and to heal’, now revealed in a new sense as scientists discover that pine scents create a cooling, aerosol effect as they rise. So a pine forest can actually create cloud cover – a natural mirror that reflects sunlight back into the stratosphere and away from the overheated earth. But there was one use of pine not mentioned by Fiona Stafford – one to which I am addicted. The seeds of the tree – called pine nuts – when harvested make a wonderful addition to many dishes, as well as being an essential ingredient of pesto sauce. Stafford did, however, mention the heady scent of pine trees which I particularly associate with the Mediterranean.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1887

Paul Cezanne, The Great Pine, c.1896

Something else overlooked by Stafford, but which I would have to mention in any discussion of pines, are Paul Cezanne’s paintings of pine trees which frame Mont Saint Victoire in his many paintings of that mountain. Most powerful of all – and one of my absolute favourite paintings – is his portrait of The Great Pine.

A hawthorn in the Yorkshire Dales

“There is a Thorn—it looks so old,

In truth, you’d find it hard to say

How it could ever have been young,

It looks so old and grey.

Not higher than a two years’ child

It stands erect, this aged Thorn;

No leaves it has, no prickly points;

It is a mass of knotted joints,

A wretched thing forlorn.

This is the opening stanza of Wordsworth’s poem ‘The Thorn’, cited by Fiona Stafford as an example of the fearsome reputation of the hawthorn, regarded throughout history as so unlucky that its blossom should never be brought into the house or displayed. Indeed, I remember when I was a child, my mother, who hailed from rural Derbyshire, would be horrified if we came back from a walk with hawthorn in amongst a bunch of wild flowers). This fear probably derived from the erroneous belief that Christ’s crown of thorns was of hawthorn. From the belief flowed the idea that to bring any part of the tree into a house – but most importantly the flowers – would result in someone in the house dying. Attacking or cutting down a hawthorn tree was a bad idea for the same reason. As Stafford remarked in her talk, ‘Some terrifying force seems to lurk within this formidable tree – or rather in the minds of those who feel so threatened by its deeply feminine beauty’.

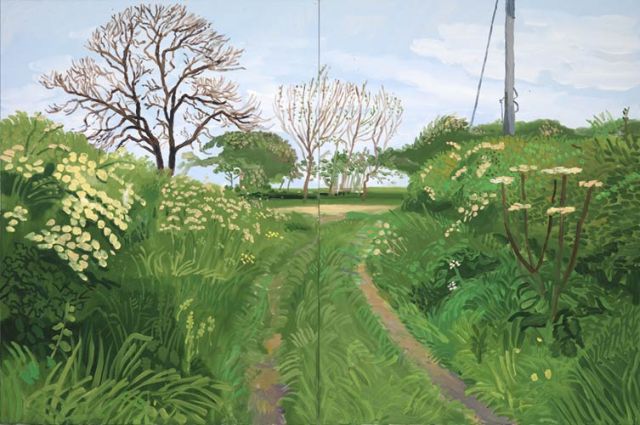

In spring, the hawthorn bursts into beautiful ‘May’ blossom. Every year, in Stafford’s words, ‘almost overnight the hawthorn turns white; huge heaps of flowers seemed to be dropped along the branches as if by some careless cook. For David Hockney, this is ‘action week’. At his landmark exhibition in London a couple of years ago, a whole room was filled with ‘these huge, disturbing, custard-coated forms’ – a massive celebration of the magical, shape-changing hawthorn’.

Hockney, ‘May Blossom on the Roman Road’, 2009

Despite the hawthorn’s association with bad luck, the tree’s main association is with May, its blossom crowning May queens and adorning maypoles. Its alternative name of May or May blossom reflects the fact that the flowering of the hawthorn is a sign that winter is over and spring is underway (although, given the British climate, May blossom might appear in April or as late as June). Interestingly, the old saying ‘Ne’er cast a clout ’til May be out’ (a warning not to be precipitous in shedding any clouts or clothes) refers, not to the month of May, but to the understanding that summer has not arrived until the May blossom is out.

May blossom on Wenlock Edge, May 2007

Coincidentally, Paul Evans, one of the finest observers of the natural world writing at present, has this week devoted his Country Diary in the Guardian to the hawthorn. I think the piece merits being reproduced in its entirety:

The last May blooms like a bride on Windmill Hill. White in the evening light as the sky begins to clear from a cool, drizzly day, she stands as a lightning rod, still dazzling with energy from the recent storm. From lightning, according to myth, she originated. Her branches are filled with corymbs of five-petalled flowers, each with a ring of red, match-head stamens. Her earthily erotic musk draws flies for pollination and sends them into a trance. A sacred tree to European peoples, her wood was used in wedding torches in Greece, as protection against hauntings and evil spirits in Germany, and in magical healing for warts, toothache, rheumatoid arthritis and childbirth.

Crowns of mayflower were found on the dead of Palaeolithic cave-dwellers long before they were used as bridal wreaths in Greek and Roman weddings dedicated to Maia and the Virgin Mary. In Celtic culture, lone bushes like this one were places of fairy power and protected for fear of reprisals. There is something in this. I have long admired this particular tree: impenetrable and cloud-shaped, it flowers late and produces a big crop of scarlet haws. It is frequently full of birdsong and the hum of insects, and has a distinctive presence up on top of the hill as a kind of beacon. It would feel like sacrilege to interfere with it and I can well believe its beauty could turn to malevolence. Most May trees or hawthorns in the landscape have gone smudgy, their petals fading and dropping in the rain.

Paths and lanes all around are sprinkled with the white confetti of the great wedding of May, and now the month and its tree are nearly over. The next wave of rose relative flowers – bramble and dog rose – is about to break out of hedges and scrub. Until then, this tree says it all in dazzling simplicity: flowers and thorns, beauty and pain – the marriage of May.

The hawthorn, as Stafford rightly stated, has changed the entire face of Britain: it’s a palimpsest of old land practices. This hardy tree, when cut and laid, is in many ways responsible for our very idea of the British countryside because of its usefulness for hedging. When much of Britain was enclosed in the eighteenth century, the new fields were marked by hawthorn tree hedges, shaping the landscape into the familiar patchwork of fields. Fields bounded by hawthorn hedges form a deeply-ingrained mental image of the English landscape – which is why the uprooting of old hedgerows in modern farming practice can be such a psychological shock. More than that, the loss of hawthorn hedgerows has also had an impact on wildlife, contributing to the decline of many species of bird. In his poem ‘The Thrush’s Nest’, John Clare observed the close affinity between hawthorn and thrush:

Within a thick and spreading hawthorn bush

That overhung a molehill large and round,

I heard from morn to morn a merry thrush

Sing hymns to sunrise, and I drank the sound

With joy; and often, an intruding guest,

I watched her secret toil from day to day –

How true she warped the moss to form a nest,

And modelled it within with wood and clay;

And by and by, like heath-bells gilt with dew,

There lay her shining eggs, as bright as flowers,

Ink-spotted over shells of greeny blue;

And there I witnessed, in the sunny hours,

A brood of nature’s minstrels chirp and fly,

Glad as the sunshine and the laughing sky.

A typical poplar-lined road in the south of France (photo by Brian Jones, http://bracken.pixyblog.com)

When, in the 1970s, we began travelling through France to campsites in the Dordogne or Cevennes, the element of the landscape that most impressed itself upon me was that of miles of poplars that lined the routes nationales as we drove south. In her essay on the poplar, Fiona Stafford noted that many of those in northern France were planted all in one go, on the instruction of Napoleon, in order to shade troops as they marched towards the French border. The fact that they rapidly grew tall in orderly rows meant that they were perfect for lining trunk roads, or for gentlemen – who, on the Grand Tour, had seen the ‘Lombardy Poplar’ lining roads and rivers in northern Italy and had decided to utilise them line avenues on their country estates.

Poplars by the Mersey near Sale

Poplar, said Stafford, is not much good as wood these days (it’s mainly used for matches), but is, surprisingly, the most modern of trees, being the first tree to have had its complete DNA sequenced. This breakthrough has allowed experiments in tree breeding to begin – with objectives such as combating carbon emissions, and developing bio-fuels and bio-degradable plastics.

For such a plain, column like tree there are, surprisingly, many literary references to poplars. Among those mentioned by Fiona Stafford was ‘Binsey Poplars’, written by Gerard Manley-Hopkins as an early protest against tree-felling – an act of ‘spiritual vandalism’ – when the poplars in the water meadows at Binsey were cut down. It was a landscape that Hopkins had known intimately while studying at Oxford, and the felling ‘symbolized the careless destruction of nature by modernity’:

felled 1879

My aspens dear, whose airy cages quelled,

Quelled or quenched in leaves the leaping sun,

All felled, felled, are all felled;

Of a fresh and following folded rank

Not spared, not one

That dandled a sandalled

Shadow that swam or sank

On meadow & river & wind-wandering weed-winding bank.

O if we but knew what we do

When we delve or hew —

Hack and rack the growing green!

Since country is so tender

To touch, her being só slender,

That, like this sleek and seeing ball

But a prick will make no eye at all,

Where we, even where we mean

To mend her we end her,

When we hew or delve:

After-comers cannot guess the beauty been.

Ten or twelve, only ten or twelve

Strokes of havoc unselve

The sweet especial scene,

Rural scene, a rural scene,

Sweet especial rural scene.

Then there are the many artistic representations of poplars – ranging from Turner and Monet (the many paintings in all seasons of the poplars on the banks of the river Epte) and Van Gogh (who painted poplars many times in his life) to Paul Cezanne and Roger Fry.

JMW Turner, A distant castle with poplar trees beside a river,1840

Poplars on the Epte by Claude Monet, 1891

Claude Monet, Sunlight Effect under the Poplars,1887

Paul Cézanne, Poplars, 1890

Roger Fry,River with Poplars, 1912

Avenue of Poplars at Sunset by Vincent van Gogh, 1884

Vincent van Gogh, Two Poplars on a road through the hills, 1889

Earlier I mentioned Cezanne’s obsession with painting the pines that framed the view of Mont St Victoire he saw every day when he climbed the hill above his home outside Aix-en-Provence. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I don’t think he ever painted the poplars cypress [see comment below!] which rise in the foreground of that view. Maybe they weren’t there in the 1880s, though they were present when I photographed the scene a few years ago.

Poplars and Mont St Victoire

Whatever their economic or utilitarian value, the thing about trees for me is their daily presence in the world around us – ‘constant as the northern star’ as Joni Mitchell wrote in an entirely different context. Constant and yet ever-changing: they may be the most important means by which we measure the seasons. There is, too, something almost inexpressible about how we live out our lives amongst living things which – if they can escape the chainsaw – can survive for centuries or even millennia. They are truly, in the words of a poem by WS Merwin which coincidentally appeared in Saturday’s Guardian, the way we see the world:

‘Elegy for a Walnut Tree’ by WS Merwin

Old friend now there is no one alive

who remembers when you were young

it was high summer when I first saw you

in the blaze of day most of my life ago

with the dry grass whispering in your shade

and already you had lived through wars

and echoes of wars around your silence

through days of parting and seasons of absence

with the house emptying as the years went their way

until it was home to bats and swallows

and still when spring climbed toward summer

you opened once more the curled sleeping fingers

of newborn leaves as though nothing had happened

you and the seasons spoke the same language

and all these years I have looked through your limbs

to the river below and the roofs and the night

and you were the way I saw the world

See also

- The Meaning of Trees: previous post discussing series one

- ‘The blood-red brilliance, mystery and melancholy of the hawthorn’

Requiem for a tree: a ‘luminous emptiness’

Back in September, in Sefton Park on the trunk of a spreading beech tree I pass every day walking our dog, a notice appeared. Following an inspection of trees in the park, it stated, this tree had been identified as hazardous, its continued existence posing an unacceptable threat to the public. Urgent and drastic action was required and the tree would be felled within days.

It’s always sad to come across a tree laid, low in a winter storm maybe, that has fallen under its own weight or weakened by old age. But to see a fine tree condemned to death in hours is a sad thing indeed.

Enquiries suggested that the beech had become hazardous as a result of infection spreading through the root system. Two days later the process of felling the tree began: all the major limbs and branches were removed, and the tree remained for several more days, reduced to a bare, leafless skeletal trunk. Then, finally, one morning’s walk revealed the end: the trunk felled and sliced up into heavy sections.

There is a beautiful passage in Hermann Hesse’s Trees: Reflections and Poems, originally published in 1984 that expresses very well the sense of loss that I felt:

Nothing is holier, nothing is more exemplary than a beautiful, strong tree. When a tree is cut down and reveals its naked death-wound to the sun, one can read its whole history in the luminous, inscribed disk of its trunk: in the rings of its years, its scars, all the struggle, all the suffering, all the sickness, all the happiness and prosperity stand truly written, the narrow years and the luxurious years, the attacks withstood, the storms endured. And every young farmboy knows that the hardest and noblest wood has the narrowest rings, that high on the mountains and in continuing danger the most indestructible, the strongest, the ideal trees grow.

Last month Seamus Heaney died, so some of his poetry was fresh in my mind. His 1987 collection, The Haw Lantern, includes a sequence, ‘Clearances’, in memory of his mother. In his collection of essays, The Government of the Tongue, Heaney discussed this poem, of how it was inspired by a chestnut tree his aunt planted in her yard the same year he was born. Through all his years of growing, he identified with the tree and felt a deep sense of loss years later when he heard that the family that had moved into his aunt’s house after her had cut it down. Writing about his mother’s death in ‘Clearances’, the memory of the tree returned, or rather he wrote, ‘the space where it had been’ did: ‘a kind of luminous emptiness, a warp and waver of light’.

Writing about the death of his mother, that ‘luminous emptiness’ became a symbol of ‘preparing to be unrooted, to be spirited away into some transparent, yet indigenous afterlife’. It was Heaney’s expression – ‘a luminous emptiness’ – that came into my mind as I took in the space opened up by the absence of the beech tree.

…. Then she was dead,

The searching for a pulsebeat was abandoned

And we all knew one thing by being there.

The space we stood around had been emptied

Into us to keep, it penetrated

Clearances that suddenly stood open.

High cries were felled and a pure change happened.

I thought of walking round and round a space

Utterly empty, utterly a source

Where the decked chestnut tree had lost its place

In our front hedge among the wallflowers.

The white chips jumped and jumped and skited high.

I heard the hatchet’s differentiated

Accurate cut, the crack, the sigh

And collapse of what luxuriated

Through the shocked tips and wreckage of it all.

Deep-planted and long gone, my coeval

Chestnut from a jam jar in a hole,

Its heft and hush became a bright nowhere,

A soul ramifying and forever

Silent, beyond silence listened for.

The fallen oak of Pontfadog

We used to have a caravan just outside Glyn Ceiriog, near Chirk in north Wales. The road approaches the village winding through the beautiful valley of the Ceiriog river, and a few miles before arriving in Glyn Ceiriog you pass through the hamlet of Pontfadog. There, once, stood an oak tree, the oldest tree in Wales, the third largest in Britain and one of the oldest in Europe.

That is where, in June 2005, I took the photos that open and close this post. It was the last time that we visited this gnarled and ancient tree, attended by its black guard dog. Now, after standing for around 1,500 years, the Pontfadog oak has fallen, blown down by gales that swept across North Wales on 17 April (while we were away in Naples).

There was some uncertainty about exactly how old the tree was because it had lost its heartwood. But it was certainly ancient: a National Trust tree expert calculated in 1996 that it had stood at least 1,181 years, and possibly was as old as 1,628 years. ‘I cannot find a record of an oak tree of any of the 500 species internationally which has a greater girth anywhere in the world’, he wrote. What had been called ‘Wales’s national tree’ had a girth measured at over 53ft in 1881.

The tree occupied no special place in the village of Pontfadog – it did not stand on a village green, but instead was approached across a farmyard, presided over when we visited by a large black dog. The oak stood near to the farmhouse, by a gate that led into a hillside meadow. There were no signs, no celebratory plaques.

The oak, and the farm on whose land it stood, had been in the Williams family for generations. ‘It was always a working tree, pollarded or pruned for its wood. It was part of the community. People built houses from it, cooked from it. That’s why it lived so long. It always had a role,’ Moray Simpson, tree officer for Wrexham county borough council, told the Observer.

We forget, these days, just how important these oaks were in medieval times, primarily as a source of timber for buildings. Oliver Rackham, in his History of the Countryside, estimates that 90% of medieval building timbers are oak. Although oak was the most common timber tree, it was the most expensive; other species – elm or ash, for example – are more often found in medieval terrace houses and the homes of the relatively poor.

But most medieval buildings are made from large numbers of small oaks; every timber, Rackham says, was taken from the smallest tree that would serve the purpose. It was a skilled job: oaks are crooked, and carpenters had to make ingenious use of the irregular shapes into which they grow. Remarkably, a typical 15th century farmhouse was constructed from around 330 trees. Small trees, though: usually 9 inches or less in diameter, so perhaps many timbers came from the pollarded trees to which Moray Simpson referred.

In his poem ‘Oak’, Michael Hamburger meditates on the ‘loss of that patient tree, loss of the skills/That matched the patience, shaping hard wood/To outlast the worker and outlast the user’:

Slow in growth, late in putting out leaves,

And the full leaves dark, austere,

Neither the flower nor the fruit sweet

Save to the harsh jay’s tongue, squirrel’s and boar’s,

Oak has an earthward urge, each bough dithers,

Now rising, now jerked aside, twisted back,

Only the bulk of the lower trunk keeps

A straight course, only the massed foliage together

Rounds a shape out of knots and zigzags.

But when other trees, even the late-leaved ash,

Slow-growing walnut, wide-branching beech and linden

Sway in a summer wind, poplar and willow bend,

Oak alone looks compact, in a stillness hides

Black stumps of limbs that blight or blast bared;

And for death reserves its more durable substance.

On wide floorboards four centuries old,

Sloping, yet scarcely worn, I can walk

And in words not oaken, those of my time, diminished,

Mark them that never were a monument

But plain utility, and mark the diminution,

Loss of that patient tree, loss of the skills

That matched the patience, shaping hard wood

To outlast the worker and outlast the user;

How by oak beams, worm-eaten,

This cottage stands, when brick and plaster have crumbled,

In casements of oak the leaded panes rest

Where new frames, new doors, mere deal, again and again have

rotted.

After the Pontfadog oak fell, the local memories surfaced: a missing bull had once spent two days inside the hollow trunk; two golden chisels were said to have been hidden in it; in 1880, six men could be seated around a table inside it; it was used by sheep both as a shelter and somewhere to die; children used to play in it; Victorians posed for photographs by it; and generations carved their initials in it. And there was Welsh legend: in 1157 before he took on and defeated the English King Henry II, the Welsh prince Owain Gwynedd rallied his army under the tree, and later, when the English king had his men cut down the Ceiriog woods in 1165, the tree was spared.

Here’s a pertinent poem, ‘The Fallen Oak’ by Giovanni Pascoli (translated from the Italian):

Where its shade was, the oak itself now sprawls,

lifeless, no longer vying with the wind.

The people say: I see now—it was tall!

The little nests of springtime now depend

from limbs that used to rise to a safer height.

People say: I see now—it was a friend!

Everyone praises, everyone cuts. Twilight

comes and they haul their heavy loads away.

Then, on the air, a cry—a blackcap in flight,

seeking a nest it will not find today.

Naturally, there was sorrow at the loss of such a venerable living thing – and some recriminations. In December 2012, the Woodland Trust presented a petition with 5,300 signatures to the Welsh Assembly noting the tree’s fragility and calling for better protection. But the £5,700 cost was considered too high, so nothing was done. But, maybe we should just accept the hand that fate dealt: in Woodlands, Oliver Rackham points out that great storms and the felling of trees, rather than being a disaster, can be an unmitigated benefit for wildlife. Monotonous areas of shade are broken up, creating new habitats. And most uprooted trees survive, sprouting from the base and sometimes along the trunk, calling into question, he writes, ‘the assumption that the ‘normal’ state of a tree is upright’.

See also

- The Pontfadog oak was the oldest of the old, revered, loved … and now mourned (Observer)

- Pontfadog oak: description on the Monumental Trees website with several photos of the tree before it fell

- Oak tree around since the Vikings blown down (Daily Mail report with photos)

- Expert says 1,200-year-old oak tree near Oswestry cannot be saved (Shropshire Star)

The Meaning of Trees

Who would have thought that the dark grey shapes in a pack of dog biscuits are derived from willow ash, a product which aids digestion and reduces flatulence? This was just one of the fascinating insights offered by Fiona Stafford, Professor of Literature at Somerville College Oxford, in a series of Radio 3 essays last week entitled ‘The Meaning of Trees’.

In her talks, Fiona Stafford explored the cultural, economic and social significance of five different trees – yew, ash, oak, willow and sycamore – outlining the symbolism and importance of each tree in the past and their changing fortunes and reputations. She revealed how some trees are yielding significant new medical and the environmental benefits.

So, for example, in her first essay Stafford noted that the Yew has been labelled ‘the death tree’ because of its toxicity: every part of the tree is poisonous, and it bleeds a remarkably blood-red sap. Yet today these ancient trees have the most modern of uses – as part of the fight against cancer.

Yews are renowned for their astonishing longevity, and are most often associated with churchyards. Yet, as Stafford pointed out, many ancient yews pre-date the churchyards where they stand. They mark ancient, sacred sites on which Christianity, as the new religion, built. Yews continued to be planted in churchyards where their toxic leaves would not endanger grazing livestock.

The Fortingall Yew in Perthshire (above) is Europe’s oldest tree at over 3,000 years old, and was already a veteran when the Romans arrived. Stafford spoke of how the astonishing longevity of the yew and its evergreen branches have suggested comforting thoughts of everlasting life to mourners in churchyards, while the dark, dense boughs offer privacy and stillness.

A distinctive feature of yews is that they don’t conform to any standard, but evolve into many diverse shapes and forms. They were tamed and trimmed in Renaissance mazes and parterres, and over the centuries some have grown into fantastical forms, as we saw for ourselves some years back at Powis castle in Wales, where the terrace is bounded by a 30 foot yew hedge and huge strange shaped ‘tumps’ formed over the centuries by the annual round of clipping and shaping. (below).

But, said Fiona Stafford, the yew also gained a reputation as ‘the death tree’, due to its toxicity – every part of the tree is poisonous. Shakespeare described the tree as ‘double fatal’ – its boughs poisonous, while arrows crafted from yew also brought death. The yew, that bleeds red with remarkably blood-red sap if its bark is cut, has triggered deep fears: yews are there in ghost stories and gothic horror and loom through the gathering darkness of Gray’s Elegy. In Tennyson’s In Memoriam, the yew is both resented for still being alive when his friend is dead, but also celebrated for its longevity:

Old Yew, which graspest at the stones

That name the under-lying dead,

Thy fibres net the dreamless head,

Thy roots are wrapt about the bones.

The seasons bring the flower again,

And bring the firstling to the flock;

And in the dusk of thee, the clock

Beats out the little lives of men.

O not for thee the glow, the bloom,

Who changest not in any gale,

Nor branding summer suns avail

To touch thy thousand years of gloom:

And gazing on thee, sullen tree,

Sick for thy stubborn hardihood,

I seem to fail from out my blood

And grow incorporate into thee.

With its blood-red berries and leaves resistant to winter’s trials, yews were a symbol of everlasting life, the oldest living things in Europe. The longevity of the yew was illustrated by Fiona Stafford when she told how, at Fountains Abbey in the 12th century, the yews were already so large that the monks could live in them while the abbey was being built. Some living yews are older than Stonehenge or the pyramids. Trees that were seedlings 3000 years ago were already vast by time Romans arrived.

The idea of the yew symbolizing everlasting life might now be reinforced, Stafford argued, by the tree’s new role in the fight against cancer. In the 1960s, scientists discovered that taxol, derived from the bark of the yew, could be used in chemotherapy. A newer formulation is now used to treat patients with lung, ovarian, breast and other forms of cancer.

But there’s a downside for the tree: stripping bark from the trees kills them, and as a consequence the Himalayan Yew is now an endangered species. Careful harvesting of yew needles would produce the same benefits and be more sustainable but, being slower, yield lower profits. ‘The impulse to fell’, Stafford concluded, ‘has a humane as well as a profit dimension’. This is not the first time that human exploitation has threatened the yew: Stafford described the medieval decimation of the European yew for arrows.

But, Stafford concluded, it is not the yew’s dark façade or poisonous needles but its very long life that is troubling: the tree will survive into a future when we’ve all been forgotten. If all that’s left of the people who planted some of our more venerable trees are their broken beakers, she queried, what will remain of those in today’s garden centres trundling their potted yews to the checkout? Their purchase may be their most long-lasting legacy.

Although we don’t yet know what else the yew has hidden away, one day we might. What is the meaning of the yew? Stafford concluded: it’s much too early to say.

In her second essay, Fiona Stafford tackled the tree which has suddenly hit the headlines. The Ash is now threatened by the arrival in Britain of the fungus called Chalara fraxinea which causes ash dieback. But, said Stafford, the Ash has survived since the birth of humanity and has met mortal threats before. Despite many different near fatal epidemics over the centuries, delicate ash trees have survived for millennia.

As evidence of the significance of the Ash in our culture and for the British landscape, Stafford cited David Hockney’s recent Royal Academy show in which ash trees peopled the fields of the Yorkshire Wolds (above) – a return, she said, to the great tradition of British landscape painting. [For a discussion of the prospects for the trees painted by Hockney, see Will Ash Dieback affect Woldgate Hockney Trees?]

Stafford cited John Constable as an example of another English painter in love with the graceful form of the ash. The tree figures in paintings such as Cornfield and Flatford Mill, and in drawings which Constable made of a favourite ash on Hampstead Heath (below).

In the summer of 1823 Constable rented a house in Hampstead. He admired trees and made many studies of them, always noting their specific shapes and varying foliage. In this drawing – Study of an ash tree – inscribed and dated ‘Hampstead June 21 1823. longest day. 9 o clock evening – he defined the particularities of an ash tree at a given moment and at a specific location, combining intense feeling for the tree with accurate observation of the tree trunk, branches and leaves, as well as capturing the air between the leaves and the wind passing through.

Stafford told how Constable described the tree as having died of a broken heart after a notice warning against vagrancy was nailed unceremoniously to the trunk. ‘The tree seemed to have felt the disgrace’, he lamented, for almost at once some of its top branches withered, and within a year or so when the entire tree became paralysed, and ‘the beautiful creature was cut down to a stump’. His friend and biographer C.R. Leslie wrote of Constable’s love of trees, and of the ash in particular:

I have seen him admire a fine tree with an ecstasy of delight like that with which he would catch up a beautiful child in his arms. The ash was his favourite, and all who are acquainted with his pictures cannot fail to have observed how frequently it is introduced as a near object, and how beautifully its distinguishing peculiarities are marked.

It was a favourite tree, too, of Edward Thomas. In Ash Grove, written in 1916, war has concentrated his mind on a vision of England, at ‘a moment’, in Stafford’s words, ‘when the past, unwilling to die, floods the present with joyful sunlight, and an ordinary clump of trees becomes magnified into something extraordinary’. Thomas also evokes his Welsh ancestry in the poem’s recollection of a girl singing the old Welsh folk song ‘The Ash Grove’:

Half of the grove stood dead, and those that yet lived made

Little more than the dead ones made of shade.

If they led to a house, long before they had seen its fall:

But they welcomed me; I was glad without cause and delayed.

Scarce a hundred paces under the trees was the interval –

Paces each sweeter than the sweetest miles – but nothing at all,

Not even the spirits of memory and fear with restless wing,

Could climb down in to molest me over the wall

That I passed through at either end without noticing.

And now an ash grove far from those hills can bring

The same tranquillity in which I wander a ghost

With a ghostly gladness, as if I heard a girl sing

The song of the Ash Grove soft as love uncrossed,

And then in a crowd or in distance it were lost,

But the moment unveiled something unwilling to die

And I had what I most desired, without search or desert or cost.

Stafford discussed the many cultural associations of the ash, including its health benefits. Pliny noted that its leaves were considered an effective antidote to snake bites, while later generations valued the ash as a cure for obesity and gout, and its bark a tonic for arthritis, while warts could be eradicated by a prick from a pin that had been inserted into the bark.

The ash was an integral part of life, giving its name to innumerable places, and wherever people lived and worked the ash tree was a constant companion. Its reputation as a friend to man rested not only on its physical beauty or medicinal value, but also the versatility of ash wood. Its toughness and elasticity lent itself to the manufacture of wagon wheels, skis, walking sticks, bentwood chairs, as well as cricket stumps and billiard cues. Stafford told how, during the Second World War, when metal was scarce, ash was used in construction of the de Havilland Mosquito, a wooden bomber. Ash was also the wood used for the Morris Traveller wood frame, and is still used today in the construction of Morgan sports cars.

Given the ubiquity of the tree, it was not surprising, Stafford suggested, that the ancient people of northern Europe thought the entire world depended on the ash. In Nordic myth, even human beings were thought to derive from piece of ash driftwood the Norse gods found on the shore. Ask was the first human, created by the gods from that piece of ash; in Old Norse askr means ‘ash tree’.

Our history with the ash is long. In Norse mythology, the World Tree Yggdrasil was an ash tree, with two wells feeding its roots – wisdom and destiny. Stafford told how Norse mythology also ‘foresaw the end of the known world when Yggdrassil would shake and crack, the land would be engulfed by ocean, and the old gods overthrown. They knew that the great ash tree would not last forever.’ But, asked Stafford, can we protect the ash now that it fights off a new threat to its existence?

She pointed out that ashes not renowned for their longevity, living only a couple of hundred years at most. But coppiced they will continue to send up shoots from the dead heartwood, and their abundant seeds – or keys – also lead to rapid propagation. The ash is tolerant of almost any soil, and – until now – has been one of most familiar trees in Britain. It is hard to imagine an ash-less Britain, but, with Chalara fraxinea now alarmingly set on sweeping through British Isles, Stafford concluded, ‘the future of the ash tree is far less assured than its past’.

Fiona Stafford began her essay on the Oak in that most English of locations – the bar of the Royal Oak. Here, in a pub bearing the third most popular pub name in England, you are likely to be surrounded by oak – the bar and tables made of oak, and the beer’s flavour and colour deepened in oak barrels. Oak, she said, is such an integral part of our culture we scarcely notice it.

Sturdy, stalwart, stubborn: the oak is a symbol of enduring strength that has inspired poets, composers and writers for millennia. But not just in England. The oak has been chosen as the national tree of many other countries, too, including Estonia, France, Germany, Moldova, Romania, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the United States, and Wales.

Civilisations have been built from oak, as its hard wood has been felled for houses, halls and cities, its timber turned into trading ships and navies. Other woods are as strong, but few are as long-lasting as oak. Some oak trees, observed Stafford, served as ale houses, some were gospel oaks under which parishioners gathered to hear readings from the Bible. She might have added that the spreading branches of others served as shelter for local council meetings – such as the Allerton Oak (above) in Liverpool’s Calderstones Park, now over a thousand years old, beneath which the sittings of the local ‘Hundred court’ were held.

When war threatened, oak proved crucial for national defence, oak wood being unique for its hardness and toughness and thus ideal for shipbuilding. But the oak’s value also led to its decimation since a large naval vessal required some 2000 oaks, and replanting was a slow affair, with replacement trees only reaching maturity after two or three hundred years.

In one of the most fascinating parts of her talk, Fiona Stafford explained that the English are not alone in identifying the oak as a symbolic tree. The oak is the emblem of Derry in Northern Ireland, originally known in Gaelic as Doire, meaning oak. The Irish County Kildare derives its name from the town of Kildare which originally in Irish was Cill Dara meaning the Church of the Oak. The oak is a national symbol for the people of the Basque Country, as well as being used as a symbol by a number of political parties, including the Conservative Party. As Stafford observed:

The outspread arms of the oak offered a congenial symbol and make the complicated story of its political exploitation a telling example of how different notions of nationhood can be cultivated, felled, or replanted. If the same tree can inspire both conservative admiration for inheritance and radical enthusiasm for equal rights, as well as unionist pride in inclusiveness and separatist determination for independence, it’s difficult to be too absolute about what the oak’s real meaning might be.

Sacred to the Celts and the Ancient Greeks, the oak tree has been central in British culture, present in place-names and national songs; yet it is also the national tree of dozens of countries. It was once the most common European tree, but then the huge demand for oak timber led to a steep decline. Commenting on the famous Major Oak of Sherwood Forest (above), Stafford wondered:

‘Is the Major Oak in Sherwood Forest, its collapsing branches so carefully cradled by poles and wires, a heartening image of a caring community, or does it provoke less cheering ideas of a people clinging to memories of a great, but increasingly vanishing past?’

But then, she concluded, perhaps the impulse to interpret trees as anything but trees is one to handle with care.

The poor soul sat singing by a sycamore tree.

Sing all a green willow:

Her hand on her bosom, her head on her knee,

Sing willow, willow, willow:

The fresh streams ran by her, and murmur’d her moans;

Sing willow, willow, willow

– Othello, Act IV, Scene 3

Fiona Stafford began her essay on the Willow by observing that for poets and dramatists it has long been the tree of loss, abandoned lovers, and broken hearts. Shakespeare had Desdemona singing her willow song on the last night of her life and Ophelia sinking into the brook by the willow:

There is a willow grows askant a brook,

That shows his hoar leaves in the glassy stream;

There with fantastic garlands did she come: [….]

There, on the pendent boughs her coronet weeds

Clambering to hang, an envious sliver broke;

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook.

Something about this tree, it seems, makes everyone want to weep – but the problem, as Stafford pointed out, is that many such references to the willow in folk songs (and in Shakespeare) pre-date the arrival of the Weeping Willow in Britain in the 18th century. It’s claimed that the Weeping Willow was first introduced by the poet Alexander Pope who received a basket of figs from Smyrna in Turkey. Noticing that one of the twigs making up the basket was still alive, he planted it in his garden in Twickenham where it grew into the willow tree from which, it’s claimed, all others have been propagated. By early 19th century the Weeping Willow was widely recognised, not least due to the willow pattern pottery designed by ceramics artist Thomas Minton (who also invented the legend which the design illustrates).

So Shakespeare’s willow, and the willow of old folk songs, must have belonged to one of the many indigenous varieties – white willow, crack willow, bay willow, etc, etc. The easiest of trees to propagate, the pliable branches of the quick-growing willow have been used for basket-weaving, wicker-work, cradle-making, thatching or fencing. Osiers, the shrubby willows (above), are the best for basket-making, with stems so strong and pliable that they can be woven into wickerwork without snapping.

A dramatic symbol of the past importance of the willow for local economies is, as Fiona Stafford noted, Serena Delahaye’s giant willow man (above), a prominent landmark beside the M5 northbound between junction 24 and 23, near Bridgwater in Somerset. The sculpture stands 40 feet high and is made of locally grown black maul willow, woven around a steel skeletal frame. The current figure is the second on the site. The original was destroyed by fire in 2001. We have seen it from a speeding car on our way to Cornwall: a celebration of the traditional local industry of the Somerset Levels. Fiona Stafford offered a reminder that in Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees, Roger Deakin devoted a chapter to the willow growers of the Somerset Levels.

The willow’s fortunes have fluctuated over the centuries, according to the practical needs of the time. In times of war its lightness and flexibility meant that it was used to make artificial limbs, while willow charcoal was used to make gunpowder. Doctors also used the charcoal for dressing wounds, and willow was used as a remedy for fever and rheumatism. Pain relief derived from the willow’s salicylic acid, which yielded aspirin. Eventually this led to the development of salacin, an anti-inflammatory agent that is produced from willow bark and which is closely related in chemical composition to aspirin. Willow charcoal is not only the best for sketching, but has also been used to manufacture medicinal biscuits aimed at aiding digestion – thus the grey dog biscuits mentioned at the start.

The willow’s flammability (which led to its use in making gunpowder) mean that it is now being developed for biomass. In Scandinavia, willow wood chip is already replacing oil as a cleaner fuel for domestic heating, as well as for industrial purposes. Willows offer a reliable, carbon-neutral source of heat – they grow so fast, absorbing carbon dioxide, that they can be harvested very frequently, producing cheap and easily-renewable supplies of fuel. Willow-fuelled power stations being planned. Willows could also form part of an effective defence against flooding, with the long roots thriving in moist soil and helping to stabilise river banks.

So, synonymous with Englishness, having furnished the raw material for cricket bats since the 1780s (when a new variety of white willow was identified in Suffolk, providing an especially resilient, wide-grained wood) the willow is now at the cutting edge of medicinal and biomass development.

Fiona Stafford finished her survey of the willow’s meaning, by noting that when Claude Monet was trying to achieve ‘the ideal of an endless whole, unlimited by shores and horizons’, he turned again and again to the lily pond at Giverny. ‘It was’, said Stafford, ‘as if he could paint with plants, filling the pool with water lilies, surrounding it with weeping willows. In the paintings, planes and surfaces dissolve as the multi-petalled flowers float on reflections of trees, and the vertical fronds of the willows make waves more visible than water’.

‘Monet’s willows’, concluded Stafford, ‘are perhaps the ultimate image of the ever-shifting willow: a tree so adaptable that it can be taken for water, sky, earth or sun. And what might the willow be saying? So much depends on the circumstances’.

In massy foliage of a sunny green

The splendid sycamore adorns the spring,

Adding rich beauties to the varied scene,

That Nature’s breathing arts alone can bring.

Hark! how the insects hum around, and sing,

Like happy Ariels, hid from heedless view—

And merry bees, that feed, with eager wing,

On the broad leaves, glazed o’er with honey dew.

The fairy Sunshine gently flickers through

Upon the grass, and buttercups below;

And in the foliage Winds their sports renew,

Waving a shade romantic to and fro,

That o’er the mind in sweet disorder flings

A flitting dream of Beauty’s fading things.

– John Clare, ‘The Sycamore’

There’s a tall sycamore that stands in a neighbouring garden and in summer, from mid-afternoon, casts our lawn and patio into deep shade. It has annoyed me through the thirty-odd years that we lived here, and I have longed for it to be cut down.

In her final essay, Fiona Stafford challenged the popular image of the Sycamore as an unwanted, problematic weed, the cause of ‘the wrong kind of leaves on the line’ that disrupt British railways each year; the tree with too many leaves, too much sap, and too many seedlings.

Instead, Stafford focussed on the benefits of the sycamore. As John Clare observed in his poem, with its dense foliage and sweet sap the tree is a haven for insects and sipping bees. Clare, said Stafford, was ahead of his time in understanding this. The sycamore is now valued, too, as a haven for all kinds of birds.

Sycamores annoy because of their resilience. Sycamore seeds, with their propellers, spread far and wide on the wind and take root anywhere. They are hardy trees, loved by urban councils for their resistance to salt and tolerance of the pollution and harsh environment of city streets. Consequently, the sycamore has become the most common tree in British cities.

In Britain, as Stafford noted, attitudes to the sycamore have always been ambivalent. Already, in 1664, John Evelyn was asserting that the sycamore should be banished from gardens and avenues because of its reputation for shade, and the honeydew-coated leaves which, after their fall, ‘turn to a mucilage … and putrefie with the first moisture of the season [and so] contaminate and marr our Walks’. Many continue to hold such views, and see it as a weed which should be eradicated. As Richard Mabey observes in his magnificent book Weeds:

The mythology stacked against it is formidable. It’s a true weed, invasive and loutish. Its myriad seedlings swamp the ground and out-compete native trees. Its large and ungainly leaves litter the earth, then slowly rot to a slithery mulch. They are ‘the wrong sort of leaves’ that famously cause trains to skid to a halt every autumn.

But as both Stafford and Mabey observe, though widely regarded as a non-native species, the sycamore was introduced to Britain in Tudor times while, ironically, more recent arrivals, such as 19th century exotic imports, have been highly prized.

Yet, for Stafford, there is ‘something inspirational about the ordinariness of the sycamore’. Seen as an ordinary tree, the sycamore has never been valued for its rich timber, even though its wood is as strong as oak, and more easily dyed. The sycamore, she suggested, stands for extraordinary possibilities latent in the commonplace. A familiar feature of almost every rural area, their thick foliage offers shade to sheep and cattle, shelter to solitary farmhouses, and has inspired poets as varied as John Clare and W B Yeats. In Tintern Abbey, Wordsworth expressed his profound delight in the prospect of the Wye valley seen from beneath a ‘dark sycamore’, referring to its sun-blocker foliage.

Stafford finished by recalling that the oldest sycamore in England is probably the Tolpuddle tree, beneath which gathered, in 1834, the Dorset agricultural labourers who became pioneers of the trade union movement. Barred from church halls or other indoor spaces, they gathered beneath the sycamore to stand up for their rights and resist their long hours and low wages.

The Tolpuddle sycamore

Ashes to ashes

They are that that talks of going

But never gets away;

And that talks no less for knowing,

As it grows wiser and older,

That now it means to stay.

There’s an ash that I pass each morning with the dog. I pay closer attention to the tree’s features – the grey bark, ribbed with a fine lattice pattern of ridges, the delicate leaves with their matching pairs of leaflets, and the distinctive black buds leaflets at the tip of each new shoot – now that it is like a friend of whom you hear news of a life-threatening illness. This tree looks healthy yet (photos of it illustrate this post), but the fungal spores that lead to ash dieback are advancing across the country: there has been at least one confirmed sighting in neighbouring Cheshire.

According to Oliver Rackham in Woodlands, the ash is one of the longest-established trees of these isles, advancing across the land bridge after the end of the last ice age. In that book Rackham writes that ‘trees are wildlife just as deer or primroses are wildlife. Each species has its own agenda and its own interactions with human activities’, and the spectre of losing all our ash has prompted many reflections on how deeply embedded trees are in our culture and our daily, living consciousness.

In Wildwood, Roger Deakin talked the feature of ash which has bound it to humans through time immemorial: its practical virtues as a timber, deriving from its remarkable pliability and toughness. He quotes William Cobbett, who valued the utility of ash over its beauty:

Laying aside this nonsense, however, of poets and painters, we have no tree of such various and extensive use as the Ash. It gives us boards; materials for making instruments of husbandry; and contributes towards the making of tools of almost all sorts. We could not well have a wagon, a cart, a coach or a wheelbarrow, a plough, a harrow, a spade, an axe or a hammer, if we had no Ash. It gives us poles for our hops; hurdle gates, wherewith to pen in our sheep; and hoops for our washing tubs; and assists to supply the Irish and West Indians with hoops for their pork barrels and sugar hogsheads. It therefore demands our particular attention; and from me, that attention it shall have.

Deakin points out that coopers made the hoops Cobbett refers to by cleaving coppice ash in two and bending the flat side round the barrel or washing tub. He also took advantage of the ash’s pliable nature when he created an ash bower near his home at Walnut Tree Farm:

My ash bower is a kind of folly, an Aboriginal wiltja that stands at the top of my long meadow in Suffolk. It consists of a double row of lively ash trees bent over into Gothic arches like a small church. I planted it twenty years ago. It is eighteen feet long by nine feet wide, with four pairs of trees six feet apart along each side curving up to meet just under seven feet off the ground, so you can walk up and down inside. In the summer heat it is a cool, green room roofed with wild hops and the flickering shadows of ash leaves. I sometimes sling a hammock inside. I even installed a bed last year … […]

I make no claims for the originality of its conception: it was directly inspired by David Nash’s Ash Dome. It is what they call in film or art magazines an hommage, although I prefer to hold up both hands and call it pure plagiarism. For all that, it gives me enormous pleasure and interest, and it has grown into a mild obsession. […]

The elephant-grey bark begins to gleam in a light rain shower. I love this skin of ash, almost human in its perfect smoothness when young, with an under-glow of green. It wrinkles and creases like elephant skin at the heels and elbows of old pleachers where they have healed. […]

The bower is floored in lords and ladies, ground ivy and mosses, and its eight trunks cross-gartered with wild hops, our English vines. They thatch its roof with their big cool leaves, dangling bunches of the aromatic, soporific female flowers from the green ceiling like grapes. As spring comes on, the bower fills like a bath with frothy white Queen Anne’s lace … Even at the age of twenty the trunks of the bower are beginning to show some of the early signs of what will accrue with age: they are green with algae and lichens are beginning to form around their damp feet. They are putting on ankle socks of moss. There is something goat-footed about ash trees: the shaggy signs of Pan.

Deakin speaks, too, of the characteristic flamboyance of the ash:

I love its natural flamboyance and energy, and the swooping habit of its branches: the way they plunge towards the earth, then upturn, tracing the trajectory of a diver entering the water and surfacing. In March the tree is a candelabra, each bud emerging cautiously, like the black snout of a badger, at the tip of every branch.

By the time Deakin came to write about his ash dome, in the closing pages of Wildwood, he was terminally ill, though unaware of this fact. In the book’s final passage he questions whether he was right to force the tree into the contortions required of it to form the bower; but, reasons:

I’ve done the tree no harm and in time it will grow into something beautiful as ash always does, the badger-noses on the new shoots leading the way. It doesn’t need me to teach it to dance: it is naturally playful, a contortionist with ancestral memories of tumbling with the hedger’s no less wilful strength. When the bower eventually comes of age long after I am gone, the wooden spinning top might still be going round too.

The ash dome created by David Nash on his own woodland in North Wales, is an example of a ‘growing’ work, a ring of ash trees he planted in 1977 and trained to form a domed shape. The dome is sited at a secret location somewhere in Snowdonia and whenever it’s filmed, crews are taken there by a circuitous route to guard its security. His planting of twenty two ash trees has committed him to more than thirty years of care, training and pruning and echoes his belief that he begins the works but they are completed by time and circumstance. Nash continues to maintain the Dome and records its changes in different contexts through drawings and photographs.

A couple of years back the Woodland Trust published a collection of short stories, Why Willows Weep, in which various writers each told a tale of their favourite tree. William Fiennes chose the ash in ‘Why the ash tree has black buds’:

The trees have always had some idea of what happens to them when they die. In forests they saw their neighbours toppled by wind or age and rot into earth, and their roots sent up descriptions of peat and coal in vast beds and seams. Later, when humans came along, trees saw the stockades, the carts pulled by horses, the chairs and tables set out in gardens, and quickly put two and two together. Trees growing beside rivers saw themselves in the hulls and masts of boats, and trees in orchards understood that the ladders propped against them had once been trees, and when men approached with axes to fell them, the trees recognized the handles.

Trees often wondered what their particular fate might be. Would they subside into the long sleep of coal, or blaze for an hour in a cottage grate, or find themselves reconfigured as handle, hurdle, post, shaft, stake, joist, beam – or something more elaborate and rare: an abacus, a chess piece, a harpsichord? And out of these dreams a rumour moved among the trees of the world like a wind, not quite understood at first, it was so strange – a rumour that when they died, instead of being burned, planed, planked, shimmed, sharpened, many trees would be pulped. This was an entirely new idea to trees, whose self-image was all to do with trunk, sturdiness, backbone, form. But trees are good at getting the hang of things, and soon they understood that from pulp would come the white leaves humans called paper, and that these leaves would be bound into books, and after a short season of anxiety in which conifers shed uncharacteristic quantities of needles, the trees came to terms with this new possibility in the range of their afterlives.

Yes, the trees recognized themselves in paper, in books, just as they recognized themselves in all the other things that hadn’t been thought of quite yet, like bedsteads and bagpipes and bonfires, not to mention violins, cricket bats, toothpicks, clothes pegs, chopsticks and misericords. Men and women would sit in the shade of trees, reading books, and the trees, dreaming of all that was to come, saw that they were the books as well as the chairs the men and women sat in, and the combs in the women’s hair, and the shiny handles of the muskets, and the hoops the children chased across the lawns. The trees took pride in the idea of being a book: they thought a book was a noble thing to become, if you had to become anything – a terrible bore to be a rafter, after all, and a wheel would mean such a battering, though of course the travel was a bonus, and what tree in its right mind would wish to be rack, coffin, crucifix, gallows . . .