Matisse in Focus at Tate Liverpool brings together fifteen paintings from the Tate collection to provide an overview of the artist’s work across five decades. Its centrepiece is The Snail, the largest and most popular of Matisse’s cut-out works; after this show closes, it will never travel outside London again. Continue reading “Matisse in Focus at Tate Liverpool: The Snail’s last outing”

Tag: sculpture

Antony Gormley: Being Human

Alan Yentob’s film for the BBC’s Imagine strand last week made a powerful case for Anthony Gormley being one of the most original and profound of British artists at work today. In Antony Gormley: Being Human, Alan Yentob followed the sculptor to recent exhibitions of his work in Paris and Florence, and explored the influences that have shaped his life and work. Continue reading “Antony Gormley: Being Human”

Total eclipse: darkness and light

In anticipation of tomorrow’s great astronomical event, I have been recalling the last (and only) time I witnessed a total solar eclipse.

In Cornwall on 11 August 1999 we saw the last total eclipse that was visible over the UK (though, last time, totality was only fully visible along a limited path that crossed northern France and Cornwall). Typically, being Britain, the skies were cloudy, and we didn’t get to see the disc of the moon passing across the sun. But, at 11 minutes past 11 in the morning, standing on the cliffs above Sennen Cove in Cornwall, it did go spookily dark – not total darkness, but the dark of deep dusk. And we did see the moon’s shadow advancing towards us from the west, and the receding to the east. Continue reading “Total eclipse: darkness and light”

Germany: Memories of a Nation

This week Neil MacGregor’s superb series for BBC Radio 4, Germany: Memories of a Nation, reaches its conclusion – fittingly timed to coincide with Germany’s Schicksalstag, or Fateful Day, the ninth of November. In our lifetime it’s the opening of the Berlin wall on 9 November 1989 that we all remember. But, strangely, a succession of significant events in German history have occurred on 9 November. In 1938, in the Kristallnacht, synagogues and Jewish property were burned and destroyed on a large scale; in 1923 it was Hitler’s failed Beer Hall Putsch, marking the early emergence of his Nazi Party on Germany’s political landscape; in Berlin on 9 November 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and two German republics were proclaimed – the social democratic one that was eventually known as the Weimar Republic, and Karl Liebknecht’s Free Socialist Republic; further back, in 1848, the year of revolutions, on 9 November Robert Blum, the democratic left liberal leader was executed by Austrian troops, leading to hopes for a united, democratic Germany being extinguished for another half century. Continue reading “Germany: Memories of a Nation”

Went for bread, met a head bound for Norway

At the end of my previous post I encountered a giant iron elephant. A day later, picking up my Saturday sour-dough loaf from the incomparable Baltic Bakehouse, I found my way blocked by a giant bronze doll’s head. Such is life.

For several months now I have not been able to eat bread from anywhere but the Baltic Bakehouse, a fairly recent addition to Liverpool’s independent retail scene, where they produce the finest sour-dough loaves. They have names like Moss Lake Wild and Baltic Wild, though my favourite at the moment is their Granary. They also make cakes and croissants to die for. There’s an interesting article about them on the Seven Streets blog.

Staff of life: Baltic Bakehouse bread (photo by Seven Streets)

Last Saturday, turning into Bridgewater Street I found my way blocked by some pretty heavy lifting machinery. Clearly something was going on, so I took a look. A few doors down from the Bakehouse is Castle Fine Arts Foundry, another artisan outfit that, in the words of their website, has been ‘proudly serving sculptors for more than twenty years’. They have cast a fair few pieces that we have seen displayed at Yorkshire Sculpture Park where I had been 24 hours earlier. In Liverpool, the best-known work which came from Castle Fine Arts Foundry is the Hillsborough Memorial on Old Haymarket, created by sculptor Tom Murphy in bronze.

The Hillsborough Memorial on Old Haymarket.

This is what I saw: a giant sculpture being gingerly manoeuvred out of the foundry workshop. It was a very delicate operation: I stood watching for about half an hour, and it took that long to get the whole piece out of the door. Around two that afternoon I was another errand near Penny Lane when I met the head, strapped on a low-loader and heading out of town. It had taken something like four hours to pull it out of the workshop and then lift it onto the low-loader.

Big head blocking road

A delicate operation

Chatting with members of the team who were supervising and filming the delicate operation, I learned that the head was on its way to a park in Oslo. The huge doll’s head had been designed by Norwegian sculptor Marianne Heske to be place on a hillside in Torshovdalen Park in a suburb of Oslo. She had chosen a position from where visitors to the park can sit and have a clear view of both the sculpture and Oslo fjord. Heske selected the spot two years ago, with the help of a giant balloon.

Heske, with the aid of a balloon, marks the spot for her doll’s head

The doll’s head has been major leitmotif of Heske’s work for decades – specifically, a 1920s doll’s head – girlish lips, arched eyebrows, tightly bobbed hair – that she found in Paris in the 1970s. According to Frieze:

Its image recurs throughout her work from that decade, as Heske, in common with other artists practising in mainland Europe at the time, extended the conceptual trajectory started by Fluxus. This mass-produced head became, for her, a symbol of humanity, a representative of the anonymous individual among the masses. In various works and in different media – from photo-montage and lithography to assemblage and even film – she combined its image with scientific diagrams of skulls and phrenological charts and mappings, explorations of the systems used to classify consciousness, and to label individuals.

Marianne Heske with doll’s head maquette

After graduating from Bergen Art College, Marianne Heske left Norway and lived first in Czechoslovakia, still behind the Iron Curtain, where she discovered Land Art, being made by Czech artists who didn’t have access to ordinary art materials because they didn’t conform to the dictates of Soviet official art policy. Then she went to live in Paris, which was where she found the box of doll heads in a flea market. They were pouting papier mache heads with baby-doll faces, pencil-thin eyebrows, and rosebud lips. Heske liked them because ‘they all looked the same, all playing their role, and because dolls are a mirror of society. So I bought the whole box. I brought it home and started to work’.

The Head finally clears the workshop

Head is an enlargement of one of those doll’s heads bought by Heske at the Paris flea market in 1971. It is 7 metres in height and is cast in bronze. The head is hollow, ‘so there’s room for big thoughts’, says Heske.

Hours later, the Head on the low-loader, passes the Anglican cathedral

The official unveiling will take place in Torshovdalen Park, Oslo on 12 June.

Ai Weiwei in the chapel at YSP: ‘The art always wins’

‘Iron tree’ by Ai Weiwei outside the chapel at Yorkshire Sculpture Park

At Yorkshire Sculpture Park they recently completed the renovation of a sandstone chapel built in 1744 for the owners of Bretton Hall, the Palladian mansion that stands at the heart of the estate now devoted to art. The chapel was a place of worship for the owners of the estate and the local community for over 200 years until it was deconsecrated in the 1970s. Enter it now and you enter a contemplative space occupied by a new installation by Ai Weiwei, a profound and meditative work by an artist whose government has strictly limited his travel and confiscated his passport.

Fairytale – 1001 Chairs consists of 45 antique Chinese chairs dating from the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), each one different and yet arranged so uniformly in nine orderly rows in the nave, each chair occupying an identical, rigorously-defined space so that they seem to lose their individuality. And this is exactly Ai Weiwei’s point.

Unable to travel to Yorkshire, and working from plans and photographs of the chapel, Ai selected 45 chairs from a project displayed in Kassel in 2007 for which he brought (metaphorically) 1001 Chinese citizens to Kassel for 20 days, representing each person (otherwise unable to travel outside China) with an antique chair. Ai Weiwei chose 1001 to make a point about the collective and the individual: 1000 is a mass, one is an individual.

Ai Weiwei, ‘Fairytale-1001 Chairs’ (photos by Jonty Wilde, courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park)

In the chapel you are invited to choose a chair and sit. You are handed poems to read by Ai Weiwei’s father, Ai Qing (1910-1996). For this is art that is both deeply political and more meditative than any other work by Ai that I have seen. The tranquil space, with its plain stone floor and bare whitewashed walls invokes stillness. As sunlight slants through the unembellished windowpanes, Ai’s Fairytale Chairs and his father’s words combine to provoke thoughts about power, privilege and the freedom of individual. The chapel is a refuge, a sanctuary in which thought can take wing.

The individual: detail from ‘Fairytale-1001 Chairs’ (photo by Jonty Wilde, courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park)

Each of these chairs is a valuable antique which once would have seated a privileged member of Chinese society, and now might be bought at a great price and leave China to stand in the room of a wealthy individual on the far side of the world. To be invited to sit on a chair like this is a freedom not granted to our Chinese contemporaries. These chairs were once the preserve of the privileged, but now – through Ai Weiwei’s intervention – as the crowds of visitors to the YSP sift through the chapel and sit for a moment’s contemplation, they represent democracy.

Society allows artists to explore what we don’t know in ways that are distinct from the approaches of science, religion and philosophy. As a result, art bears a unique responsibility in the search for truth.

Ai Weiwei’s work repeatedly draws attention to unethical government policies. He gained international attention for his collaborative work on the design of Beijing’s National Stadium,nicknamed the Bird’s Nest, built for the 2008 Olympics (he later said that he was ‘proud of the architecture, but hated the way it was used’). His work has often been angry and controversial, including the series of photographs in which he gave the finger to the Chinese government and other international leaders, and breathtaking installation in Munich created from 9,000 children’s backpacks which was his protest over the thousands of students killed when their schools collapsed in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake (he blamed the death toll on the Chinese government corruption that permitted shoddy construction).

For nearly a decade, Ai has been harassed, placed under constant surveillance, and sometimes imprisoned. In 2011, state police seized him, threw a black bag over his head and drove him to an undisclosed location, where he languished for 81 days in a tiny prison cell. He is now banned from leaving China and his home remains under constant surveillance. Despite these restrictions, Ai has continued his criticism of the Chinese Communist leadership – which he regards as repressive, immoral and illegitimate – in works that demonstrate a deepening concern with autocratic power and the absence of human rjghts. Were it not for his international celebrity and the worldwide protests last time he was jailed, Ai would probably be in prison like Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, who is serving an 11-year sentence.

Ai’s political activism and confrontational art stem from a tumultuous childhood. In the chapel I sit for a while and read poems by his father, Ai Qing, one of China’s most revered poets, who was imprisoned by Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party in 1932. It was during the three years he spent in jail that Ai Qing began to write poetry. During the Sino-Japanese war (1931-45), swept along by the rising storm of patriotism in China, Ai Qing travelled to Yan’an, in northern China, the centre of the Communist-controlled area. He officially joined the Party in 1941, and was once close to Mao Tse-tung, who talked to him on several occasions about literary policy. His poems from this time reveal an empathy with China’s poor and their harsh existence. One of the poems I had been given to read was ‘The North’, written in 1938 in Tongguan; this is the last stanza:

I love this wretched country,

This age-old country,

This country

That has nourished what I have loved:

The world’s most long-suffering

And most venerable people

Ai Qing’s poems celebrated the natural world and the lives of ordinary people – and the Communist cause, as here in these lines from ‘The Announcement of the Dawn’, another poem available to read in the chapel:

For my sake,

Poet, arise.

And please tell them

That what they wait for is coming.

Tell them I have come, treading the dew,

Guided by the light of the last star.

I come out of the east,

From the sea of billowing waves.

I shall bring light to the world,

Carry warmth to humankind.

Poet, through the lips of a good man,

Please bring them the message.

Tell those whose eyes smart with longing,

Those distant cities and villages steeped in sorrow.

Let them welcome me,

The harbinger of day, messenger of light.

Open every window to welcome me,

Open all the gates to welcome me.

Please blow every whistle in welcome,

Sound every trumpet in welcome.

Let street-cleaners sweep the streets clean,

Let trucks come to remove the garbage,

Let the workers walk on the streets with big strides,

Let the trams pass the squares in splendid procession.

Let the villages wake up in the damp mist,

And open their gates to welcome me …

Ai Qing joined the Communist Party in 1941, and for a time was close to Mao Tse-tung, with whom he would sometimes discuss literary policy. When Ai Qing returned to Beijing in 1949 he was already a cadre in the new government, and began to concentrate his talents more and more on writing poems in praise of Mao Tse-tung and Stalin. Then, in 1958, he wrote a poem that extolled the virtues of a culture that celebrated rather than repressed multiple voices. For this he was publicly denounced as ‘a rightist’ and exiled with his family to a re-education camp, where he was humiliated, beaten and forced to clean toilets for nearly two decades. Ai Weiwei was one year old and spent his early years in the camp, then another 16 years in exile before the family was allowed to return to Beijing in 1976 following the death of Mao and the end of the Cultural Revolution. In an interview with David Sheff in 2013, Ai Weiwei recalled the years of exile:

I’m a person who likes to make an argument rather than just give emotion or expression a form and shape in art. I became an artist only because I was oppressed by society. I was born into a very political society. When I was a child, my father told me, as a joke, “You can be a politician.” I was 10 years old. I didn’t understand it, because I already knew that politicians were the enemy, the ones who crushed him. I didn’t understand what he was talking about. But now I understand. I can be political. I can say something even though we grew up without true education, memorizing Chairman Mao’s slogans. I memorized hundreds of them. I can still sing his songs, recite his poetry. Every morning at school we stood in front of his image, memorizing one of his sentences telling what we should do today to make ourselves a better person.

Another poem by Ai Qing that I read as a sit in the stillness and light of the chapel at the YSP is ‘Wall’, written on a visit to Germany in 1979. These are the opening and closing stanzas:

A wall is like a knife

It slices a city in half

One half is on the east

The other half is on the west

How tall is this wall?

How thick is it?

How long is it?

Even if it were taller, thicker and longer

It couldn’t be as tall, as thick and as long

As China’s Great Wall

It is only a vestige of history

A nation’s wound

Nobody likes this wall

[…]

And how could it block out

A billion people

Whose thoughts are freer than the wind?

Whose will is more entrenched than the earth?

Whose wishes are more infinite than time?

Ai Weiwei has selected three more works for the chapel. ‘Ruyi’ (which means ‘as as one wishes’ is a vividly-coloured porcelain sculpture in the form of a traditional Chinese sceptre of the same name, used by nobles, monks and scholars for around 2,000 years. Ruyi denoted authority and granted individuals the right to speak and be heard, ‘thus enabling orderly and democratic discourse’.

Ai Weiwei, ‘Map of China’, 2008 (photos by Jonty Wilde, courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park)

Map of China is a massive piece, carved from wood reclaimed from dismantled Qing dynasty temples. On the wall opposite are displayed two timelines. One consists of some of the terrible dates in China’s history in the last 100 years: the estimated famine deaths across China (five million in 1928-30; 10 million in 1943; 25-45 million after the end of the Great Leap Forward in 1961); troops opening fire on demonstrators in Tiananmen Square, Beijing in 1989; the 8.0-magnitude earthquake that hit Sichuan province, killing tens of thousands in 2008. In a parallel column are listed dates very personal to the artist: 1932, his father, the celebrated poet Ai Qing, begins to write because he cannot paint while imprisoned as a member of the League of Left Wing Artists; 1958, Ai Qing interned in a labour camp as a “rightist” with his family, including the baby Ai Weiwei, where he spends the next 16 years cleaning the village toilets.

Then there are recent dates from the artist’s own life: 2008, artistic adviser for the Olympic stadium; 2009, project to publish all the unacknowledged names of child victims of the earthquake, and cranial surgery following assault by police; 2010, house arrest as ‘Sunflower Seeds’ opens at Tate Modern; 2011, accused of ‘economic crimes’ and imprisoned for 81 days, his Shanghai studio demolished. The most recent date simply reads: ‘2014, passport confiscated’.

Ai Weiwei, Lantern, 2014 (Photo by Jonty Wilde, courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park)

Upstairs is ‘Lantern’, carved in marble excavated from the same quarries used by emperors to build the Forbidden City, and more recently, to build Mao’s tomb. For some years the Chinese authorities have surrounded Ai’s home with surveillance cameras and every step he takes outside is recorded and monitored. In a gesture of mockery and defiance, Ai began to decorate the CCTV cameras with red Chinese lanterns. Then he began to carve the ‘Lantern’ series from marble. In this way the ephemeral becomes permanent, or – as Ai has said – ‘The art always wins. Anything can happen to me, but the art will stay.’

Ai Weiwei: ‘Iron Tree’, 2013

One tree, another tree,

Each standing alone and erect.

The wind and air

Tell their distance apart.

But beneath the cover of earth

Their roots reach out

And at depths that cannot be seen

The roots of the trees intertwine.

– Ai Qing, ‘Tree’,1940

Stepping out of the chapel into the sunlight you are confronted by one of Ai’s most recent works – the six-metre high ‘Iron Tree’, the largest and most complex sculpture to date in a tree series begun in 2009, and inspired by pieces of wood sold by street vendors.

Ai Weiwei: ‘Iron Tree’, 2013, details

The work has been constructed from casts of branches, roots and trunks from different trees. Although like a living tree in form, the sculpture is very obviously pieced and joined together with large iron bolts. ‘Iron Tree’ comprises 97 pieces cast in iron from parts of trees, and interlocked using a classic – and here exaggerated – Chinese method of joining, with prominent nuts and screws. The work ‘expresses Ai’s interest in fragments and the importance of the individual, without which the whole would not exist’.

Creativity is the power to reject the past, to change the status quo, and to seek new potential. Simply put, aside from using one’s own imagination – perhaps more importantly – creativity is the power to act. Only through our actions can our expectations for change turn into reality.

– Ai Weiwei

Footnote

It’s 25 years since a million protesters demanding democratic freedoms gathered in Tiananmen Square, only for the protests to be brutally crushed. Good piece in the Guardian by author of Beijing Coma, Ma Jian who took part in the protests and is now exiled.

See also

- Ai Wei Wei: the unharmful, gentle soul misplaced inside a jail

- Ai Weiwei: throwing stones at autocracy

- Ai Wei Wei’s sunflower seeds at Tate Modern

- Ai Weiwei: ‘I have to speak for people who are afraid’

The Great War in Portraits: patriotism is not enough

William Tickle volunteered aged 16 and died 22 months later on the third day of the Battle of the Somme

The recognition that something terrible, something overwhelming, something irreversible had happened in the Great War explains its enduring significance for those born after the Armistice. For this war was not only the most important and far-reaching political and military event of the century, it was also the most important imaginative event.

– Jay Winter, The Great War and the Shaping of the 20th Century

The Great War mobilised 70 million people, killed over 9 million on active service, and left behind 3 million widows and 10 million orphans. It was also, as Jay Winter observes, an event that seared itself into the European imagination, as The Great War in Portraits, the excellent exhibition currently showing at the National Portrait Gallery, clearly demonstrates. I saw it when in London recently.

Jacob Epstein, Torso in Metal from ‘The Rock Drill’, 1916

The Great War represented a fracture in the narrative of progress: a leap into modernity that was also a fire-storm of barbarity. It accelerated the momentum towards a world dominated by machines of unparalleled power whilst at the same time precipitating a descent into barbarity on an industrial scale. Perhaps no work of art represents this paradox more clearly than Jacob Epstein’s altered 1916 version of The Rock Drill, exhibited here as a prelude to the exhibition.

In its original form it was the product of the experimental pre-war days of 1913, when Epstein was associated with the short-lived Vorticism movement, enraptured by visions of technological power and transformation. Then the figure exuded power and virility, but in 1916, in response to his growing horror of the conflict, Epstein discarded the drill, dismembered the figure and cut it in half, leaving a one-armed torso. The truncated version appears defenceless and melancholic, evocative of the wounded soldiers who were returning home from the trenches in startling numbers; as the gallery caption puts it:

Thus transformed it evokes the way the experience of war shattered initial expectations – aggression giving way to a sense of loss.

Jonathan Jones writing in the Guardian in 2011 summed up the meaning of the The Rock Drill with these words:

During the first world war, as the reality of trench warfare as industrialised slaughter became clear to a world that at first welcomed the conflict, Epstein cast the torso of his eerie creation in metal. Robbed of its legs and towering tripod-drill, with damaged bronze limbs, The Rock Drill becomes a nightmare image of the future as remorseless, unending war. It is more moving than the original, because it is a wounded machine, a human machine.

In its dismembered 1916 form Torso in Metal echoes Self-portrait as a Soldier by Ludwig Kirchner, encountered later in the show.

The Great War in Portraits brings together images of individuals involved in the conflict from the National Portrait Gallery and other collections, including material from the Imperial War Museum. The exhibition presents a wide range of visual responses to the war: alongside paintings and drawings, there are photographs, posters, memorabilia and examples of how the war was represented in the newest art form of the time – film.

At the culmination of the exhibition we come face to face with the shocking violence of Expressionist masterpieces by Beckmann and Kirchner, drawings of young soldiers with grotesque facial wounds, and an entire wall upon which is displayed a grid of forty photographs, representing the wide diversity of individuals from across the world who were sucked into the vortex of war. The exhibition is crammed into a small space, and when I was there people were packed shoulder to shoulder. But no-one spoke. There was complete silence: the shocked and sorrowful silence of the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

All of the survivors are gone now – yet, as the centenary of the outbreak of the war approaches, the cultural memory of the Great War remains potent, and is indeed reinforced by this exhibition. The concept of ‘cultural memory’ has become central to much of the historical writing about the war in the last 50 years. Jay Winter’s book, quoted earlier, is one example – and itself owed a debt to the classic work of Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory. Central to the idea of cultural memory is the argument that personal memories are not the product of solitary reflection alone, but are shaped by ideas and actions within the groups to which we belong – family, workplace and nation, for instance – and conveyed through writings, monuments and cultural artefacts. This exhibition demonstrates how this process of shaping our memory of the war began even before the war had ended.

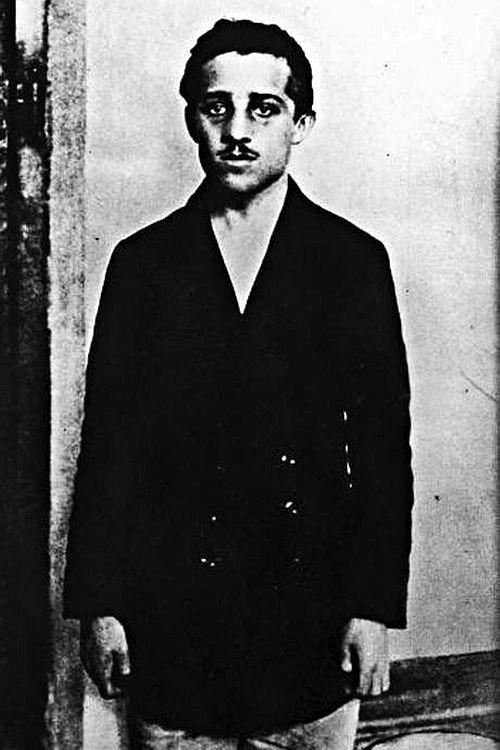

Gavrilo Princip in a police photograph taken after he had assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand

‘Royalty and the Assassin’, the first room in the exhibition, focuses on the leaders of the main countries involved in the war. Here are conventional portraits of royalty in which the prevailing tone is of grandeur and pride. Alongside is a photograph of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie taken in Sarajevo on 28 June 2014 an hour or so before their deaths at the hand of their assassin, the Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip whose police mug shot, taken after his arrest, is also displayed.

William Orpen, Portrait of Haig at General Headquarters, France, 1917

In the next section, ‘Leaders and Followers’, formal and traditional portraits of the military leaders face anonymous portraits of ordinary soldiers on the other side of the room. Here, for instance is France’s Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the Supreme Allied Comamnder, the German Chief of General Staff Paul von Hindenburg, and Field Marshal Douglas Haig, ‘the colossal blunderer, the self-deceived optimist, of the Somme massacre of 1916’ (Vera Brittain’s words). Despite the vast number of casualties in that disaster of a few months earlier, no trace of trauma can be found in William Orpen’s 1917 portrait. Upright and garlanded with medals, he stares out with bland assurance.

William Orpen was a financially successful pre-war society portraitist, appointed an official war artist in 1917, who made drawings and paintings of privates and German prisoners of war as well as official portraits of generals and politicians like this one. The official ‘power portraits’ of military leaders were widely reproduced, notably as collectable postcards, and a selection are displayed here.

William Orpen, A Grenadier Guardsman, 1917

On the opposite walls are portraits of ordinary soldiers – in battle, at rest and waiting to be laid to rest. The contrast is between the authority figures who are celebrated and the ordinary soldier who is invariably depersonalised and anonymous. As a curator’s caption notes:

A hierarchical order of seniority, influence and role was clear in the various images of the participants that were created. Irrespective of nationality, formal portraits of commanding officers are essentially traditional images that emphasise the personal profile of the depicted individual. This is manifest in their attitude of authority and, often, an impressive array of medals signifying power and gallantry. The depiction of ordinary servicemen was markedly different – a more down to earth view, depicted either as anonymous or as generic ‘types’. The impression conveyed is one of a depersonalised, shared experience in which duty is a central assumption.

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson, La Mitrailleuse, 1915

The presence, in this section, of Nevinson’s La Mitrailleuse is evidence that for this show the curators are drawing on a wide definition of ‘portrait’. Completed while he was on home on leave from the Royal Army Medical Corps, Nevinson’s painting depicts a French machine gun team bent over their weapon. The painting invites comparison with Epstein’s Torso in Metal for, as a pre-war Futurist, Nevinson had also initially celebrated and embraced the violence and mechanised speed of the modern age. But his experience as an ambulance driver in the First World War changed his view. In his painting the soldiers appear almost like machines themselves, losing their individuality, even their humanity, as they seem to fuse with the machine gun which gives the painting its title.

Walter Sickert, The Integrity of Belgium, 1914

Sickert painted The Integrity of Belgium as a tribute to the courage of the Belgians in the defence of Liège, and sold it to raise money for the Belgian Relief Fund. Sickert never visited the front, and painted the work in his studio in London. He had been appalled by reports of German atrocities against Belgian citizens and relied on press reports and newspaper images. He was convinced that Germany had to be overpowered and that ‘the wearing effect of [the war] is worse for us non-combatants than for a soldier’. He was too old to enlist.

William Orpen, Royal Irish Fusiliers ‘Just come from the Chemical Works, Roeux, 21st May 1917′

There’s quite a lot of Orpen in this exhibition, with his sensitive drawings and paintings of other ranks being the main interest for me. Royal Irish Fusiliers ‘Just come from the Chemical Works, Roeux, 21st May 1917 is a study of an exhausted soldier slumped in a sitting position, his steel helmet balanced on his knee and his arms hanging loosely by his sides. He’s unnamed (like the Grenadier Guardsman in his oil painting on the opposite wall), but was later identified as a Sergeant Slater who was killed later in the war.

William Orpen, Sir Winston Churchill, 1916

A very different work by Orpen – though no less sensitive – is his portrait of Churchill looking weary and despondent, done in 1916 after Churchill had been blamed for the disastrous 1915 Dardanelles (or Gallipoli) campaign. Forced to resign his ministerial post in the wartime coalition government, Orpen described his painting as ‘a portrait of dejection’. (Churchill was later exonerated by a Commission of Enquiry).

Isaac Rosenberg, Self Portrait, 1915

Familiar as I was with Isaac Rosenberg’s poetry, I must admit I wasn’t aware that he also painted. So I was brought to a halt by his arresting self portrait, made in 1915. Before the war Rosenberg had been undecided whether art or poetry was his real vocation but had attend the Slade School of Fine Art, a member of that astonishing pre-war cohort that included his good friend David Bomberg, along with future luminaries such as Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, Edward Wadsworth, Dora Carrington, William Roberts, and Christopher Nevinson.

When war was declared, Rosenberg was actually in South Africa, living there with his sister in the hope that the warmer climate would cure his chronic bronchitis. The poem he wrote there – ‘On Receiving News of the War’ – is very unusual amongst early poetic responses in being decidedly anti-war:

Snow is a strange white word.

No ice or frost

Has asked of bud or bird

For Winter’s cost.

Yet ice and frost and snow

From earth to sky

This Summer land doth know.

No man knows why.

In all men’s hearts it is.

Some spirit old

Hath turned with malign kiss

Our lives to mould.

Red fangs have torn His face.

God’s blood is shed.

He mourns from His lone place

His children dead.

O! ancient crimson curse!

Corrode, consume.

Give back this universe

Its pristine bloom.

Critical of the war from the outset, Rosenberg had no patriotic desire to enlist, but needing work to support his mother, he returned to Britain where, in the autumn of 1915, he enlisted in the Army. This was the moment when he painted this self portrait.

Assigned to the King’s Own Royal Lancasters, in June 1916 he was sent with his Battalion to serve on the Western Front in France. The miseries of war began when his boots rubbed all the skin off his feet. As a soldier, he suffered more privations than the officer-poets of the First World War, enduring appalling food, atrocious hygiene and tyrannical discipline. He continued to write poetry while serving in the trenches, including ‘Break of Day in the Trenches’, ‘Returning we Hear the Larks’, and ‘Dead Man’s Dump’. He was killed by sniper fire, aged 28, on 1 April 1918.

Dead Man’s Dump

The plunging limbers over the shattered track

Racketed with their rusty freight,

Stuck out like many crowns of thorns,

And the rusty stakes like sceptres old

To stay the flood of brutish men

Upon our brothers dear.

The wheels lurched over sprawled dead

But pained them not, though their bones crunched,

Their shut mouths made no moan.

They lie there huddled, friend and foeman,

Man born of man, and born of woman,

And shells go crying over them

From night till night and now.

Earth has waited for them,

All the time of their growth

Fretting for their decay:

Now she has them at last!

In the strength of their strength

Suspended–stopped and held.

What fierce imaginings their dark souls lit?

Earth! have they gone into you!

Somewhere they must have gone,

And flung on your hard back

Is their soul’s sack

Emptied of God-ancestralled essences.

Who hurled them out? Who hurled?

None saw their spirits’ shadow shake the grass,

Or stood aside for the half used life to pass

Out of those doomed nostrils and the doomed mouth,

When the swift iron burning bee

Drained the wild honey of their youth.

What of us who, flung on the shrieking pyre,

Walk, our usual thoughts untouched,

Our lucky limbs as on ichor fed,

Immortal seeming ever?

Perhaps when the flames beat loud on us,

A fear may choke in our veins

And the startled blood may stop.

The air is loud with death,

The dark air spurts with fire,

The explosions ceaseless are.

Timelessly now, some minutes past,

Those dead strode time with vigorous life,

Till the shrapnel called `An end!’

But not to all. In bleeding pangs

Some borne on stretchers dreamed of home,

Dear things, war-blotted from their hearts.

Maniac Earth! howling and flying, your bowel

Seared by the jagged fire, the iron love,

The impetuous storm of savage love.

Dark Earth! dark Heavens! swinging in chemic smoke,

What dead are born when you kiss each soundless soul

With lightning and thunder from your mined heart,

Which man’s self dug, and his blind fingers loosed?

A man’s brains splattered on

A stretcher-bearer’s face;

His shook shoulders slipped their load,

But when they bent to look again

The drowning soul was sunk too deep

For human tenderness.

They left this dead with the older dead,

Stretched at the cross roads.

Burnt black by strange decay

Their sinister faces lie,

The lid over each eye,

The grass and coloured clay

More motion have than they,

Joined to the great sunk silences.

Here is one not long dead;

His dark hearing caught our far wheels,

And the choked soul stretched weak hands

To reach the living word the far wheels said,

The blood-dazed intelligence beating for light,

Crying through the suspense of the far torturing wheels

Swift for the end to break

Or the wheels to break,

Cried as the tide of the world broke over his sight.

Will they come? Will they ever come?

Even as the mixed hoofs of the mules,

The quivering-bellied mules,

And the rushing wheels all mixed

With his tortured upturned sight.

So we crashed round the bend,

We heard his weak scream,

We heard his very last sound,

And our wheels grazed his dead face.

Gilbert Rogers, The Dead Stretcher-Bearer, 1919

Gilbert Rogers’ The Dead Stretcher-Bearer is a shocking image, comparable Nevinson’s Paths of Glory, and is a reminder of the controversy surrounding the depiction of dead British soldiers while the war was on. When Nevinson portrayed dead infantrymen sprawled near a trench in 1917, his painting was banned. It was only after the war that the official line softened, allowing Gilbert Rogers to paint this large and harrowing picture with its blunt title. Lying in the mud, his body across the shattered remains of the stretcher on which he ferried other victims of the conflict, the man cannot be identified. His face is covered in a rain-drenched sheet, and one hand hangs above a first aid box that can now render no assistance.

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Hermann Struck, 1915

In the next section of the exhibition, ‘The Valiant and the Damned’, are grouped paintings which reflect the growing disillusionment that replaced patriotic euphoria as the war dragged on. War was now perceived as a lottery, a vortex of violence, with common humanity at the mercy of circumstance. Some achieved distinction as heroes and medal-winners. Others, shattered by their experience, returned home mutilated by wounds, or were annihilated on the field of battle.

In 1915, Lovis Corinth painted a portrait of his friend and fellow-artist, Hermann Struck. Nothing could be further removed from the image of gung-ho patriotic certainty. Corinth was co-founderr of Die Brucke, the group which had been the focus for the development of German experssionism. Struck posed for Corinth wearing the uniform of the officer he had become. Neither the subject nor the painter give in to the exalted belligerency of the moment. Instead, the painting depicts the worry, melancholy and unease of the artist in his soldier’s garb. After the war, Struck, a fervent Zionist left Europe and settled in Palestine.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Self-Portrait as a Soldier, 1915

There is another portrait here by a member of Die Brucke – also painted in 1915 and reflecting the same sense of deep anxiety and psychological disturbance as that of Hermann Struck. It’s a self-portrait by Ernst Kirchner, a key figure of the Expressionist movement whose members sought new and more direct forms of pictorial self-expression. ‘I paint,’ Kirchner said, ‘with my nerves and my blood.’

As in Corinth’s portrait of Struck, Kirchner has portrayed himself in his soldier’s uniform, in his studio before an unfinished painting and a nude model. But as if with a fearful premonition, Kirchner depicts himself as a mutilated artist, his right arm a bloody and useless stump. Kirchner was an unwilling soldier. In the spring of 1915, to avoid being conscripted into the regular infantry, he signed on as an artillery driver. Soon afterwards, he seems to have suffered a nervous breakdown, and he was declared unfit for military service that autumn. At some point during those months of mental turmoil he paintedthis self portrait. Andrew Graham-Dixon offers a revealing analysis of the painting on his website:

The setting is the artist’s studio. An unfinished painting, raw as a wound, is leaned up against one of the walls, while at the room’s centre a model poses against a black screen. Kirchner believed that study of the nude figure “in a free, natural state” was “the foundation of all visual art”. But the painter’s green-tinged, neurasthenic face is averted both from his work and its sources of inspiration. He turns instead to confront the spectator. He wears the uniform of Field Artillery Regiment No. 75, depicted with historical accuracy: dark blue uniform, trimmed with red, with red epaulets; matching cap embossed with two cockades representing Prussia and the German Reich. A cigarette dangles from the corner of his mouth and he has black unseeing eyes. According to the conventions of self-portraiture, he might have been expected to show himself holding his palette and brush. But his claw-like left hand is empty and in place of his right hand he brandishes a bloody, gangrenous stump.

Of course, the very existence of the image contradicts the situation which it apparently describes. This strikes me as an important, if generally overlooked, part of its meaning. The apparently disabled painter has painted a picture: this picture. He has evidently not been totally paralysed as an artist by his experiences in war (Kirchner was never injured and seems never to have seen active service). In my interpretation, the painting is a celebration of that fact, rather than the gloomy commemoration of a psychic wounding. I don’t even think it is, strictly speaking, a self-portrait. I think it is a portrait of the self Kirchner has escaped becoming, the self he has deliberately disabled. It is the image of the soldier whose role he refused to play. The severed hand, in my view, stands not for his inability to paint, but for his inability to fight – an inability which he welcomed and perhaps even engineered. He cannot swing a sword or fire a gun; but he can wield a brush, as the picture testifies. Through military incapacity he has preserved his potency as an artist. The picture proclaims that he could have become this hollow man, this empty warlike idol, but did not.The painting is the defiant, triumphant manifesto of a conscientious objector.

Max Beckmann, The Way Home, from the series Hell, 1919

Like Kirchner, Max Beckmann volunteered, but suffered a nervous breakdown and was discharged. The Way Home belongs to Hell, a series of lithographs in which Beckmann chronicled the lawlessness and turmoil that engulfed Germany after the November revolution of 1918. He depicts himself confronting a soldier, a disfigured amputee, returning to a vanquished nation. Beckmann reaches out to touch the amputee’s artificial arm, and gazes at the victim with profound compassion. Dedicated to portraying his pitifully damaged countrymen, he wrote in 1920: ‘We must surrender our heart and our nerves to the dreadful screams of pain of the poor disillusioned people.’

William Orpen, The Receiving Room the 42nd Stationary Hospital, 1917

As the exhibition draws to a close the images become ever more disturbing. Here is William Orpen again with a drawing done in the same year as his portrait of Churchill. It’s a study of the Receiving Room at the 42nd Stationary Hospital where he himself had been admitted, suffering from scabies. His sketch focuses on three haggard soldiers slumped on a bench waiting for treatment. ‘How more people did not die in that hospital beats me,’ remembered Orpen. ‘I personally never got any sleep, and left in a fortnight nearly dead.’

Henry Tonks, pastel portraits of soldiers with facial wounds

Still more harrowing are the images of young soldiers with grotesque facial wounds made by Henry Tonks. After the Battle of the Somme in 1916, a young surgeon named Harold Gillies became responsible for the treatment of ever-increasing numbers of soldiers who had suffered very severe damage to their faces. He established a pioneering unit at the Queen’s Hospital in Sidcup where he began to develop the techniques of plastic surgery. Gillies invited Henry Tonks to draw pastel portraits of patients before and after surgery. Tonks, formerly a professor at the Slade School of Fine Art, produced pastel drawings which are being shown for the first time here, alongside photographs taken of the soldiers at the unit run by Gillies.

Eric Kennington, Gassed and Wounded, 1918

Eric Kennington (who was born in Liverpool) was 26 at the outbreak of war, a highly skilled painter widely recognised for his technical virtuosity and exceptional draughtsmanship, and a frequent exhibitor at the Royal Academy. He enlisted with the 13th London Regiment and, lodged in poorly-maintained trenches near the village of Laventie on the Lys Valley, experienced at first-hand the privations of front-line infantry work.

He fought on the Western Front but was badly wounded and and sent home in June 1915. During his convalescence he produced The Kensingtons at Laventie, a portrait of a group of infantrymen. When exhibited in the spring of 1916 its portrayal of exhausted soldiers created a sensation.Kennington went back to France in 1917 as an Official War Artist and concentrated on depicting the common soldier; one critic wrote that Kennington was ‘a born painter of the nameless heroes of the rank and file’. After the war he designed many war memorials.

The work displayed here – Gassed and Wounded – is a scene at a field hospital where gassed and wounded soldiers are lying on stretchers. In the foreground there is a soldier with his eyes bandaged and his mouth open in pain. The painting is based on drawings Kennington made at a Casualty Clearing Station near Peronne during 1918, just as the Germans were bombarding the English lines in a prelude to their last big offensive. The painting powerfully conveys the cramped conditions and darkness of the station.

Alongside paintings and drawings, the exhibition presents examples of contemporary film and photography. The centrepiece of the show is an installation of 40 photos, arranged in grid formation, of a wide range of war participants. All of them are details cropped from vintage photographs. They depict the enormous diversity of those involved. The installation is presented as a ‘homogenised visual spectacle without identification or hierarchy … the anonymity intended to evoke a common humanity’. However, an accompanying booklet provides information about each person depicted – men and women of all nations, renowned and unknown, anonymous and famous.

Some are familiar (Robert Graves, Isaac Rosenberg, Wilfred Owen; Baron von Richthofen; Mata Hari), others less so. Here is Walter Tull, the first black officer in the British army. There is Billie Nevill, a captain who kicked a football across No Man’s Land during the battle of the Somme; Maria Botchkareva, leader of Russia’s Women’s Battalion who ended up being shot by a Bolshevik firing squad; and Harry Farr, the shell-shocked private executed for desertion in 1916 (and officially pardoned in 2006).

There are images of unidentified individuals: an unknown Gurkha; a member of the Maori Contingent; and an unidentified German prisoner, captured during the battle of Menin Road Bridge in September 1917. I noticed Paul Cadbury, a Quaker conscientious objector and volunteer with the Friends Ambulance Unit; Elsie Knocker, ambulance driver and first-aider; Edith Cavell, shot by a German firing squad on 12 October 1915; and Captain Noel Chavasse from Liverpool, one of only three people to be awarded a Victoria Cross twice. The grouping of these images underscores the indiscriminate way in which the Great War sucked people from all backgrounds into its vortex.

In an acerbic review for the Evening Standard, Brian Sewell wrote:

These images and others of their generation – of nurses, a Quaker conscientious objector, and of Harry Farr, at 25, one of the shell-shocked, witless and terrified soldiers shot for cowardice – confront us in ways beyond the reach of formal portraiture. Compare these snapshots with the life-size presence in oil on canvas of the King, the Kaiser and the aged Emperor of Austria, stern in their various panoplies of office, compare them with the slick, shallow and ill-considered portraits of the great, the good and the ordinary bloke by William Orpen (of which there are far too many in this exhibition), and ask which are the speaking likenesses, which tell the truer tale.

Frame from The Battle of the Somme, sequence 34: ‘British Tommies rescuing a comrade under shell fire’

In the final room footage from the documentary film The Battle of the Somme, released in cinemas in 1916, is screened. Made by Geoffrey Malins and John McDonell, the government did not produce the film, but they did approve it. It was highly controversial because the battle scenes were so shocking, and unlike anything screened before. Many observers felt it was too graphic. Nevertheless, 20 million people flocked to see the silent film – nearly half the population of Britain at the time.

The frame shown above is from the most memorable sequence – ‘British Tommies rescuing a comrade under shell fire’ – used in documentaries about the war ever since. The wounded soldier died 30 minutes after reaching the trenches.

Newspaper advert for a screening of The Battle of the Somme

The curators allow us to compare this British documentary with a German propagandist film, With Our Heroes on the Somme, made in 1917. It differs by not being filmed on location and the inclusion of faked shots and footage that predated the battle of the Somme. (Though the academic consensus is that one of the most famous scenes from The Battle of the Somme – of soldiers climbing out of their trench and advancing towards the enemy with some cut down by enemy fire – was not filmed during the Battle of the Somme. Rather it seems likely that Geoffrey Malins captured this scene at a training facility later.

Nearby are photographs of young men who died in the conflict. John Travers Cornwell was 15 when he joined the Navy, and 16 when, on HMS Chester, he was mortally wounded in the Battle of Jutland (he earned the Victoria Cross for his bravery). Ivor Evans also enlisted at 15, fought at Gallipoli was killed in France, aged just 18. William Cecil Tickle volunteered aged 16 and died 22 months later on the third day of the Battle of the Somme. His photo (top) poignantly bears a hand-written tribute from a member of his family.

The final exhibit is also a photograph – not the portrait of a person, but an image captured by Jules Gervais Courtellemont depicting a deserted, battle-scarred landscape. The gallery’s caption states that this is ‘the only work in the exhibition not to depict people; this poignant image is, in effect, a portrait of absence.’

Jules Gervais-Courtellemont, Devastated landscape at the French lines, c 1915

The Great War in Portraits is a poignant and challenging exhibition, though it has been forced into far too cramped a space, inexplicably pushed to the sidelines by a display of images by photographer David Bailey. Yet on the afternoon I visited the Great War in Portraits was packed, while there was hardly a soul at the David Bailey show.

In the exhibition catalogue Sebastian Faulks has written an introduction that discusses the way in which this war has come to be defined in the British memory. He notes, for instance, how the war’s last survivor Harry Patch, who believed that war was simply ‘organised murder’, was feted at his death. He quotes Wittgenstein (who fought for Austro-Hungarian Empire on the Russian front), who wrote, ‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent’. Yet there are images here that would shatter any silence, recalling words of the 19th century German dramatist and poet George Buchner: ‘Do you not hear this horrible scream all around you that people usually call silence?’

Outside in the sunshine, I paused to look at the national memorial to Edith Cavell which stands ust opposite the entrance to the National Portrait Gallery. Cavell grew up in Norfolk, before moving to London to train as a nurse in 1896. In 1907, she moved to Brussels to become the director of a training school for nurses but was caught behind enemy lines after the German invasion in 1914. The school became part of a network of safe houses created to shelter Allied soldiers before smuggling them into the Netherlands. Less than a year after the invasion, Cavell was captured by the Germans and on 12 October 1915, was executed by firing squad. Her final words were, ‘I am glad to die for my country.’ There is a story that one of the Germans in the firing squad refused to take part in the execution, throwing down his rifle when ordered to fire. He was shot by a German officer for refusing to obey orders. Inscribed on the memorial are the words she spoke to the Anglican chaplain who had been allowed to see her and to give her Holy Communion on the night before her execution:

Patriotism is not enough, I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.

The memorial to Edith Cavell in St Martin’s Place, London

See also

- The Great War in Portraits: NPG website (features podcast in which curator Paul Moorhouse introduces the key themes and works in the exhibition)

- The Great War in Portraits review: Guardian

- Gassed by John Singer Sargent: article by Andrew Graham-Dixon (Telegraph)

- A Terrible Beauty: British artists in the First World War

Another day at Another Place: looking to the horizon in silent expectation

Friday was a glorious day here in the north-west. The November sun shone in a cloudless sky of brilliant blue. An old friend was visiting, back in Liverpool for the first time in years. She had never seen Anthony Gormley’s Another Place on Crosby beach so we took her there, happy to return no matter how many times to a public art work that has grown in the affections of the public on Merseyside, and – along with Capital of Culture year in 2008 – helped to put Liverpool and Merseyside on the tourist map.

It was a perfect morning to see the installation – crisp and clear, with views across to the Wirral and beyond to the Welsh mountains. In three hours it would be high tide, and the estuary was busy with traffic taking advantage of the high water – ferries leaving, container vessels moving up-river.

We walked the length of the beach, from the low numbers to the high: Another Place consists of 100 cast-iron, life-size figures, each one numbered, spread out for about two miles along the shore, with some figures situated nearly half a mile out to sea. The figures were each made from casts of the Gormley’s own body. They stand on the beach, all of them looking out to sea, staring at the horizon in silent expectation. Gormley once said:

I think there’s that thing in Another Place of looking out. It’s what we all do: that’s why people go to the seaside, to see the edge of the world, because most of us spend most of our time in rooms.

Another Place is now a permanent fixture on Crosby beach. But we nearly lost it. The work had previously been installed at Cuxhaven in Germany, Stavangar in Norway and De Panne in Belgium before it came to Crosby in 2005 with the benefit of funding from the Mersey Waterfront Programme, the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company and Arts Council England.

However, Sefton Council had only granted temporary planning permission that was due to expire in November 2006. Despite the work attracting huge interest and drawing 600,000 visitors in 18 months, it looked as if it was destined to leave Merseyside for New York state. A second application was made extend planning permission for four months, to allow time to raise the £2.2m needed to buy the work from Gormley and maintain it thereafter. The application was rejected because of representations made to the authority that ‘several people had had to be rescued after being caught by the tide when walking out to see the most distant figures’.

But the tide of support in favour of the work’s retention was substantial: so much so that in March 2007 Sefton borough council finally announced that permission had been granted for the work to remain in place permanently. Since then Another Place has attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors and now regularly features in Liverpool tourism promotional material.

Visitors engage positively with the figures, dressing them with wigs, bikinis, hula skirts, Liverpool and Everton football shirts, seaweed dreadlocks and costumes of every description. People photograph each other with the iron men in all sorts of poses. And they pause awhile, contemplating the meaning of this artwork’s dramatic intervention in the broad sweep and big skies of the estuary landscape.

Each person leaves the beach with their own sense of the work’s meaning. For Gormley, Another Place was a poetic response to the individual and universal experience of emigration: sadness at leaving, and the hope of a new future in another place. He was interested in the motivations that link contemporary migrants, such as those who risk their lives making the perilous sea crossing from from north Africa seeking a home in Europe. He suggests that in an unequal world in which we accept the massive mobility of monetary instruments across borders, we seem to have difficulty in accepting the movement of living people.

If the work was envisaged as a response to the theme of migration, the complex administrative negotiations and arrangements in locating it here – and then ensuring it could remain – raised issues about the impact of a public artwork on the landscape. Gormley has said that the struggle over Another Place:

Illustrated that no landscape is innocent, no landscape is uncontrolled. Every landscape has a hidden social dimension to do with both its natural usage and the politics of territory. I like the idea that attempting to ask questions about the place of art in our lives reveals these complex human and social matrices.

Visiting Another Place now, nearly seven years after its installation along this shoreline, the work seems to be becoming inexorably an organic, barnacle-encrusted element in the landscape. This was Gormley’s intention: he saw the work as harnessing the ebb and flow of the tide to explore man’s relationship with nature, asking what it is to be human:

The seaside is a good place to do this. Here time is tested by tide, architecture by the elements and the prevalence of sky seems to question the earth’s substance. In this work human life is tested against planetary time. This sculpture exposes to light and time the nakedness of a particular and peculiar body. It is no hero, no ideal, just the industrially reproduced body of a middle-aged man trying to remain standing and trying to breathe, facing a horizon busy with ships moving materials and manufactured things around the planet.

The construction of Gormley’s Angel of the North in 1998 was a watershed moment in the recent story of public art; since then, Another Place has joined a lengthening catalogue of public art installations. But the public funding of art works in public places is not without its critics.

Projects such as Another Place generate a great deal of enthusiasm among local authorities (keen to promote regeneration through tourist numbers) and the arts world (keen for commissions), but sceptics believe they leave the intended audience – the public – feeling a mixture of bemusement, indifference and outright hostility. Is public art rarely more than a vanity project for those involved, reducing art to the same bracket as other civic amenities? Should genuinely public art be funded by voluntary subscription rather than tax-payers’ money? Or does state-funded public art provide a vital function in engaging those who rarely venture into galleries and enliven otherwise drab public spaces?

Gormley, when asked, ‘What’s the point of public art?’ responded simply, ‘To make the world a little bit more interesting’.

Gallery

Another Place … another day. I took these photos of the installation at sunset on a March evening in 2010.

See also

Making a beeline for Richard Long

Writing the other day about Rebecca Solnit’s history of walking, Wanderlust, I mentioned her discussion of the work of Richard Long, the land artist whose work has been dedicated to making ‘a new way of walking: walking as art’. He began in 1967 by making what was then a radically new kind of work, A Line Made by Walking,created by Long repeatedly walking a straight line in a field. Since then, he has continued to develop this idea, presenting the walks as art in three forms: maps, photographs, or text works. Each walk expresses a particular idea: so there have been walks in a straight line for a predetermined distance; walks between the sources of rivers; walks measured by tides, and walks delineated by stones dropped into a succession of rivers crossed.

Thinking about Long, I realised I had only a few days left to see the exhibition of his work that has been running all summer at the Hepworth gallery in Wakefield, with a linked exhibit at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. So, I set a course and made a beeline (quite literally as it turned out) for Yorkshire and Richard Long.

At the Yorkshire Sculpture Park I learned that the Richard Long exhibit had been located at the most distant point in the park. It seemed entirely appropriate that seeing an example of this artist’s work should require the effort of a modest walk. So follow me…

I set off down the hillside toward the lake. I love the YSP, the sense of space and varied landscapes in this vast expanse of rolling parkland, and the surprise of unexpected encounters with sculptures as you crest a rise, turn a corner or enter a glade. Currently there is a major exhibition of Joan Miro’s sculptures and other artworks, and the lawns are dotted with large bronze sculptures rarely seen outside his foundations in Barcelona and Palma de Mallorca, like Personnage, 1970 (below). Personally, I can take or leave Miro’s forms; I suppose I just don’t get them. It was interesting to browse the exhibits and read Miro’s comments on Catalan culture and art, rooted in his deep sense of national identity, in the month when the Catalan Parliament has voted to call a referendum on Catalan independence. But, like Laura Cummings in her review of last year’s Tate exhibition, Miro’s works don’t come across to me as political statements.

Walking on down the hillside I passed Jonathan Borofsky’s Molecule Man (below), aluminium gleaming in the sunlight that poured through the hundreds of holes in the sculpture that made it seem to float, light as air, giving form to the artist’s idea that the molecule structure of humans is composed of little more than water and air.

Further down, I found Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz’s monumental Ten Seated Figures, which, like most of her work, reflects her experience of war and political oppression. Abakanowicz was born in an aristocratic Polish-Russian family on her parent’s estate in Poland. The Second World war broke out when she was nine years old. The forces of Nazi Germany and then the Soviet Union swept through the land, followed by forty-five years of Soviet domination. In her work headless human figures often appear identical on the surface but on closer inspection reveal individuality, a commentary on societies which repress individual creativity in favour of collective goals and values:

My work comes from the experience of crowds, injustice and aggression…

By way of a complete contrast, near the Camellia House and in a wooded glade I encountered two works by Sophie Ryder, the artist who first drew us to the YSP many years ago with our young daughter. Crawling Lady Hare is a work behind after her exhibition here in 2008. Manus and the Running Dogs is a much earlier work from 1987, which shares a similarity – a group of animals running – to Crossing Place which we saw, again with our daughter, on the Forest of Dean sculpture trail in 1992. I love watching the faces – of children and adults alike – light up when they see a Ryder sculpture.

Emerging from the trees where leaves fell in all the colours of autumn – reds and yellows as bright as the Catalan colours of Miro’s painted sculptures back in the gallery – a cacophony of rooks or crows rose from the branches. It’s a sound that, for some inexplicable reason, always makes my heart soar.

Where the parkland slopes down to the lake, I mingled with Barbara Hepworth’s Family of Man: a group work from 1970 that consists of nine bronze upright abstract forms arranged across the sloping lawn. Each one is a simple, geometric shape, but Hepworth manages to imbue each figure with a distinctive personality. There are larger, more complex forms that seem to have distinctive male personalities, while smaller figures seem more timid, children perhaps, scared of speaking out of turn. This is a work that is best experienced outdoors, and the YSP have positioned it superbly here. As Hepworth once said:

All my sculpture comes out of landscape. No sculpture really lives until it goes back into landscape.

Down by the lake I saw a shed with a large reflective globe perched upon the roof . Now, I’ve built two sheds this year on our allotment, so I was intrigued. It turned out to be a recent work, Spiegelei, by Jem Finer, first made for the Tatton Park Biennial in 2010 and now resited here. According to the YSP’s interpretation:

‘visitors are invited into Spiegelei to experience a shift in reality, in which the world becomes inverted and sounds distorted, allowing a new and wonderful perspective on the familiar landscape of the Bretton Estate. This has been achieved through the construction of a 360-degree camera obscura using three lenses housed inside a sphere, angled to take full advantage of the views.

None of that worked for me, yet on a trip to Kent some time ago I enjoyed his Score for a Hole in the Ground, located in a wood in the Stour Valley. A seven metre high steel horn, like an old-fashioned gramophone, generates sound through rainfall. And I have been captivated by the idea of his Artangel commission Longplayer, a 1000-year long musical composition the longest non-repeating piece of music ever composed – that has been playing continuously since the first moments of the millennium, performed by computers around the world.

Then it was into the wood that surround the Lower Lake, walking a line to Richard Long.

Following the trail through the wood, every now and then I’d notice an object dangling from a tree branch, looking something like a garden bird house. In fact, collectively they are an artwork that is also an ecological intervention. The Bee Library comprises a collection of twenty-four bee-related books selected by Alec Finlay that were initially on display in the YSP Centre during springtime. Once read, each book was made into a nest for wild or ‘solitary’ bees in the grounds of the YSP. Together the library now forms an installation on a walking route which I was now following around the Upper Lake. Constructed from a book, bamboo, wire-netting and water-proofing, each nest offers shelter for solitary bees, whose numbers are in steep decline. New nests will be added in other places, building a global bee library. The Bee Poems are a collection of texts composed from a close reading of the books, published online.

I walked on, looking for Richard Long. He has written:

A footpath is a place.

It also goes from place to place, from here to there, and back again.

Any place along it is a stopping place.

Its perceived length could depend on the speed of the traveller, or its steepness, or its difficulty.

Reversing direction does not reverse the travelling time.

A path can be followed, or crossed.

A path is practical; it takes the line of least resistance, or the easiest, or most direct, route.

Sometimes it can be the only line of access through an area.

Paths are shared by all who use them.

Each user could be on a different overall journey, and for a different reason.

A path is made by movement, by the accumulated footprints of its users.

Paths are maintained by repeated use, and would disappear without use.

The characteristics of a path depend upon the nature of the land, but the characteristics can be universal.

My path finally brought me to Red Slate Line, a 1986 work made by Richard Long from slate found at the border of Vermont and New York State, and relocated here at the YSP for the summer. One strand of Long’s work is making sculptures in the landscape that are made by rearranging rocks and sticks into lines and circles without relocating them from the scene (the work is photographed, just as Andy Goldsworthy does with those works he creates that last fleetingly before they are washed or blown away, melt or decay). Meanwhile, another branch of Richard Long’s work collects up rocks, sticks or other materials to lay out those lines, circles or labyrinths on the gallery floor. In both cases, though, the landscape and the walk through it remains the primary focus.

Red Slate Line belongs to the second category – a gallery piece, now set down in a woodland setting, the shards of red slate arranged like a path leading down to the water’s edge. Rebecca Solnit wrote that these lines and circles record Long’s walks in ‘a reductive geometry that evokes everything – cyclical and linear time, the finite and the infinite, roads and routines – and says nothing’ (by which she means that we, the viewers, are given very little information about the walk that inspired them:

In some ways, Long’s work resemble travel writing, but rather than tell us what he felt, what he ate, and other such details, his brief texts and uninhabited images leave most of the journey up to the viewer’s imagination .. to do a great deal of work, to interpret the ambiguous, imagine the unseen. It gives is not a walk nor even the representation of a walk, only the idea of a walk, and an evocation of its location (the map) or one of its views (the photograph). Formal and quantifiable aspects are emphasized: geometry, measurement, number, duration.

Before visiting the YSP, I had spent some time at the Hepworth Gallery, just 15 minutes drive away in Wakefield. There, a small exhibition of work by Richard Long is just drawing to a close. The exhibition presents Long as a key figure in the emergence of land art, but notes too, that Long was also associated with Arte Povera, which questioned the boundary between art and life through the use of everyday materials and spontaneous events.

Journeying from his home town of Bristol to London, whilst a student at Saint Martin’s School of Art, Long created A Line Made by Walking (1967, above) in a grass field in Wiltshire, by continually treading the same path. It’s now been acknowledged as a pioneering artwork, incorporating performance art, land art and sculpture. The work also introduced Long’s intention to consider walking as art, exploring relationships between time, distance, geography and measurement. Long developed this intention throughout the 1970s and 1980s, making works in increasingly challenging and remote terrains and documenting the walks as texts, maps and photographs, such as Walking a Line in Peru (1972) and Sahara Line (1988). An important aspect of these works is the evidence of human activity that Long leaves as he walks, the trace of an encounter that is at the centre of the artist’s practice:

In the nature of things:

Art about mobility, lightness and freedom.

Simple creative acts of walking and marking

about place, locality, time, distance and

measurement.

Works using raw materials and my human

scale in the reality of landscapes.

Long’s sculptures occur either in the landscape, made along the way on a walk, or in the gallery, made as a response to a particular place. He works with natural materials such as sticks or slate to make sculptures and often uses mud or clay in his drawings and wall-works. This exhibition contains works from across Long’s career. It includes early photographs of his sculptures in the landscape such as Line Made By Walking and England 1968 where two paths cross in a field full of daisies.

The works in this exhibition, although made at different points in Long’s career, reflect the consistency of his approach, the same elements constant through the years:

My work has become a simple metaphor for life. A figure walking down his road, making his mark. It is an affirmation of my human scale and senses: how far I walk, what stones I pick up, my particular experiences. Nature has more effect on me than I on it. I am content with the vocabulary of universal and common means: walking, placing, stones, sticks, water, circles, lines, days, nights, roads.

– Richard Long,1983

Other photographed works on display include A Line in Japan – Mount Fuji (1979), A Circle in Alaska (1977), made of driftwood gathered on the Arctic Circle on the shore of the Bering Strait, and Circle in Africa (1978).

Circle in Africa depicts a circle made of burnt cactus branches on a rocky outcrop on Mulanje Mountain in Malawi. Long has explained how the circumstances in which Circle in Africa came about:

I was going to make a circle of stones on a high mountain in Malawi and then, when I got there, I couldn’t find any stones because there was no ice and snow to break the rock up. So I kept the idea of a circle and changed the material to burnt cacti which were lying around, that had been burnt in lightning storms. … I am an opportunist; I just take advantage of the places and situations I find myself in.

Alongside these photographs there is an annotated OS map of an area of the Cairngorms – Concentric Days, 1996 – with concentric circles superimposed, each representing a day and ‘a meandering walk within and to the edge of each circle’. You look and you imagine. There are two hand-made books – Nile (Pages of River Mud), 1990 and River Avon (1979) – both of which are assembled from papers dipped in the mud of those rivers.

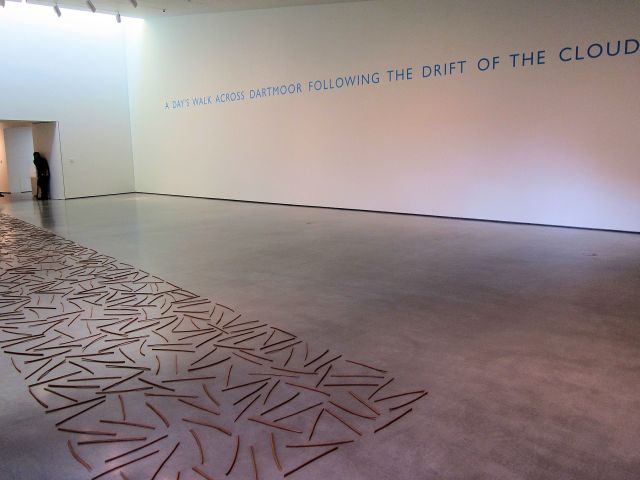

In an adjoining room are two contrasting pieces – Somerset Willow Line (1980) constructed from willow twigs arranged in a large rectangle across the gallery floor, and, spelt out in large capitals across the length of one wall, one of his text works: A DAYS WALK ACROSS DARTMOOR FOLLOWING THE DRIFT OF THE CLOUDS.

Another room brings together three more contrasting examples of Long’s work: Water Falls, a large piece like a painting created for this exhibition from paint overlain with scraped and scoured china clay, along with floor pieces, Cornish Slate Ellipse and Blaenau Festiniog Circle, constructed from blocks of Welsh slate in an arrangement that reminded me strongly of pieces exhibited by David Nash at the YSP last year.

I’ll finish with that other great walker, Robert Macfarlane. This is how he concluded an appreciation of Richard Long’s work he wrote for The Guardian:

I like his unpretentiousness. It’s probably what appeals to me most about Long and his work. He practises a kind of ritualised folk art. His circles, lines and crosses are radiantly symbolic, but also childishly simple; or, rather, they’re radiantly symbolic because they’re childishly simple. It’s for this reason that Long is ill-served by those interpreters who draw a cowl of Zennish mysticism over his sculptures, or who interpret his textworks (strings of words and phrases, often superimposed on to a photograph of the landscape that has been walked) as koan-like chants.[…]

No, Long is no magus. More of a high-end hobo. Among my favourite of his pieces is Walking Music, a textwork that records the songs that trundle through his mind as he walks 168 miles in six days across Ireland, the music keeping at bay the loneliness of the long-distance walker. Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Sinéad O’Connor singing “On Raglan Road”, Jimmie Rodgers’s “Waiting for a Train”, Róisín Dubh played on the pibroch …

Samuel Beckett – who, like Long, found much to meditate on and much to laugh at in the act of walking; and who, like Long, loved country lanes and bicycles, pebbles and circles – once observed that it is impossible to walk in a straight line, because of the curvature of the earth. There’s a great deal of Long in that remark. His art reminds us of the simple strangeness of the walked world, of the surprises and beauties that landscape can spring on the pedestrian. It’s good that Long is out there, knackering another pair of boots, singing Johnny Cash to himself as he walks the line.

See also

- Richard Long: artist’s website

- Richard Long slideshows: of sculptures, textworks and exhibitions (artist website)

- Walk the line: Robert Macfarlane on Richard Long (The Guardian)

- Richard Long interview: The Guardian

- Walking and Marking – The Art Of Richard Long: Caught By The River blog

- Richard Long: Walks on the wild side: critical assessment of Long’s work by the late Tom Lubbock (Independent)

From Earth, Light: back to Sutton Manor’s Dream

I’m writing this on a morning when the seasons seem to have shifted on their axis. Summer heat came late to these parts this year: we had to wait until September for the warmest days. Last night I lay in bed listening to the pounding of a terrific rainstorm, and this morning a brisk breeze is blowing, the temperature has dropped by ten degrees, and it is raining hailstones.

So uploading these photos taken only last Saturday feels like looking back to another season. I had some business to attend to in St Helens, so I thought I’d take the dog with me and go for a walk afterwards up to Dream at Sutton Manor. It’s been more than three years since I last went up there – soon after Jaume Plensa’s sculpture had been installed following the successful pitch by a group of former miners to Channel 4’s Big Art competition.