I was dismayed by the recent BBC TV adaptation of Great Expectations (and by the almost uniform acclaim that it received), but unsure how much my memory of the work was influenced by the David Lean film version, so I decided to read the book again. It proved to be a welcome return to a novel that had a profound effect on me as a child, with its central question as to how far the pursuit of status and wealth lead to loss of humanity: as Pip ascends he falls, and as he falls he rises.

I had great expectations of the BBC series, following as it did a recent sequence of superb BBC Dickens adaptations: Andrew Davies’ superb Bleak House (2005), Little Dorrit (2008 – Andrew Davies again), and Julian Farino’s Our Mutual Friend (1998). But this Great Expectations was a travesty, totally lacking the sense of Pip’s journey to moral awareness, as well as the one thing that makes any Dickens novel memorable and great – comedy and character. Pip is not a prig, but this was how he was presented in the TV adaptation, seemingly ignoring the fact that the novel is narrated by an older Pip looking back and reflecting subtly and frankly on his earlier fears, ambitions and limitations.

Clearly, when you’re restricted to a three hour dramatisation you can’t include everything. But to leave out the humour, to distort key characters and to omit or leave undeveloped other important characters, such as Biddy or Wemmick, was lamentable. Gillian Anderson’s portrayal of Miss Havisham was just plain daft, her youthful appearance making nonsense of the chronology of the novel. The repeated club scenes and the brothel scene took one paragraph from the novel – that has Pip and Herbert joining the Finches in Covent Garden with a very subtle hint of a brothel – and over-egged it.

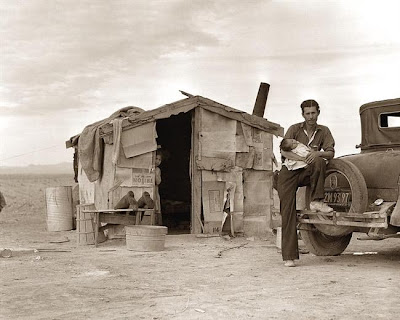

Dickens gave us characters drawn from across the whole social gamut, and was the great delineator of the gulf that separated those at either end of the spectrum. Dickens’ great theme in Great Expectations (or at least, one of them) is the dream of social betterment (a dream that is revealed as a mirage). Pip’s desire for self-improvement is the main source of the novel’s title: because he believes in the possibility of advancement, he has ‘great expectations’ about his future. Advancement may be obtained through money or by learning; but affection, loyalty, and conscience prove more important than social advancement, wealth or class.

Pip desires educational improvement: it’s a desire deeply connected to his social ambition and longing to marry Estella. A full education (as well as money) is a requirement of being a gentleman. As long as he is an ignorant country boy, he has no hope of social advancement. There’s a hilarious scene early in the novel which reveals Pip’s understanding of this fact as a child. He learns to read at Mr. Wopsle’s aunt’s dame school, where Biddy is an assistant:

The Educational scheme or Course established by Mr. Wopsle’s great-aunt may be resolved into the following synopsis. The pupils ate apples and put straws down one another’s backs, until Mr. Wopsle’s great-aunt collected her energies, and made an indiscriminate totter at them with a birch-rod. After receiving the charge with every mark of derision, the pupils formed in line and buzzingly passed a ragged book from hand to hand. The book had an alphabet in it, some figures and tables, and a little spelling,— that is to say, it had had once. As soon as this volume began to circulate, Mr. Wopsle’s great-aunt fell into a state of coma, arising either from sleep or a rheumatic paroxysm. The pupils then entered among themselves upon a competitive examination on the subject of Boots, with the view of ascertaining who could tread the hardest upon whose toes. This mental exercise lasted until Biddy made a rush at them and distributed three defaced Bibles (shaped as if they had been unskilfully cut off the chump end of something), more illegibly printed at the best than any curiosities of literature I have since met with, speckled all over with ironmould, and having various specimens of the insect world smashed between their leaves. This part of the Course was usually lightened by several single combats between Biddy and refractory students. When the fights were over, Biddy gave out the number of a page, and then we all read aloud what we could,— or what we couldn’t — in a frightful chorus; Biddy leading with a high, shrill, monotonous voice, and none of us having the least notion of, or reverence for, what we were reading about. When this horrible din had lasted a certain time, it mechanically awoke Mr. Wopsle’s great-aunt, who staggered at a boy fortuitously, and pulled his ears. This was understood to terminate the Course for the evening, and we emerged into the air with shrieks of intellectual victory.

Later, as he begins to make his way, Pip takes lessons from Matthew Pocket; and later on Pip tells of hours, days spent in extensive reading. Ultimately, though, Pip learns by absorbing lessons from his relationships with Joe, Biddy, and Magwitch, that social and educational improvement are irrelevant to one’s real worth. Wealth is not a ticket to happiness; conscience and affection are far more valuable than erudition and social standing. Joe provides a lesson along these lines early in the narrative, though Pip fails at this point to understand. He’s just admitted to Joe (the only person with whom he can be so honest) that he lied to everyone about the nature of his first meeting with Miss Havisham:

I told Joe … that I wished I was not common, and that the lies had come of it somehow, though I didn’t know how. This was a case of metaphysics, at least as difficult for Joe to deal with as for me. But Joe took the case altogether out of the region of metaphysics, and by that means vanquished it.

“There’s one thing you may be sure of, Pip,” said Joe, after some rumination, “namely, that lies is lies. Howsever they come, they didn’t ought to come, and they come from the father of lies, and work round to the same. Don’t you tell no more of ’em, Pip. That ain’t the way to get out of being common, old chap. And as to being common, I don’t make it out at all clear. You are oncommon in some things. You’re oncommon small. Likewise you’re a oncommon scholar.”

Joe offers a further lesson as he and Pip part at the end of the visit to London that has so embarrassed the young man:

“Pip, dear old chap, life is made of ever so many partings welded together, as I may say, and one man’s a blacksmith, and one’s a whitesmith, and one’s a goldsmith, and one’s a coppersmith. Diwisions among such must come, and must be met as they come. If there’s been any fault at all to-day, it’s mine. You and me is not two figures to be together in London; nor yet anywheres else but what is private, and beknown, and understood among friends. It ain’t that I am proud, but that I want to be right, as you shall never see me no more in these clothes. I’m wrong in these clothes. I’m wrong out of the forge, the kitchen, or off th’meshes.”

I had not been mistaken in my fancy that there was a simple dignity in him. The fashion of his dress could no more come in its way when he spoke these words, than it could come in its way in Heaven.

Reading these passages again, imbued with the sense of class and the perils of getting too far above yourself, I recalled how, in my teens, these ideas spoke powerfully to me as a boy from a working class background who had passed the 11 plus to go to a Direct Grant grammar. This was a school which took fee-paying boys from privileged backgrounds, whose rugby team competed in a league with public schools, and where you would be caned if you played football in the lunch hour.

Coincidentally, while I was engaged in re-reading Great Expectations, BBC 4 broadcast a documentary about grammar schools that focussed on their heyday – the period from the 1950s to the 1970s, during which they were opened up to youngsters like me from working class homes, and before the introduction nationally of comprehensive schools. What was remarkable about this film was the way in which Dickens’ theme in Great Expectations resonated throughout. Remarkable, too, was the fact that just about everyone who told their personal story ended up at some point in tears. For some, tears came with the memory of a teacher who had shown faith in their potential, for some recalling sacrifices made by parents, while for others it was the memory of tensions and conflict with parents or peers who resented their advancement or could see no point in it.

That was my story, for sure. Later, at university and doing a course in sociology, echoes of Great Expectations came back to me when we studied the research that explored the tensions of between class, culture and school. One such study was Education and the Working Class by Brian Jackson and Dennis Marsden. First published in 1962, it took a sample of 88 working-class children educated in Huddersfield and revealed how they were caught between two cultures – home and school. Meanwhile, there was Basil Bernstein’s work on language that underlined the point that the working class pupil is culturally different – but not deficient.

In Great Expectations, Dickens puts into Biddy’s words an awareness of these cultural differences:

I took Biddy into our little garden by the side of the lane, and, after throwing out in a general way for the elevation of her spirits, that I should never forget her, said I had a favor to ask of her.

“And it is, Biddy,” said I, “that you will not omit any opportunity of helping Joe on, a little.”

“How helping him on?” asked Biddy, with a steady sort of glance.

“Well! Joe is a dear good fellow,— in fact, I think he is the dearest fellow that ever lived,— but he is rather backward in some things. For instance, Biddy, in his learning and his manners.”

Although I was looking at Biddy as I spoke, and although she opened her eyes very wide when I had spoken, she did not look at me.

“O, his manners! won’t his manners do then?” asked Biddy, plucking a black-currant leaf.

“My dear Biddy, they do very well here —”

“O! they do very well here?” interrupted Biddy, looking closely at the leaf in her hand.

“Hear me out,— but if I were to remove Joe into a higher sphere, as I shall hope to remove him when I fully come into my property, they would hardly do him justice.”

“And don’t you think he knows that?” asked Biddy.

It was such a very provoking question (for it had never in the most distant manner occurred to me), that I said, snappishly,—

“Biddy, what do you mean?”

Biddy, having rubbed the leaf to pieces between her hands,— and the smell of a black-currant bush has ever since recalled to me that evening in the little garden by the side of the lane,— said, “Have you never considered that he may be proud?”

“Proud?” I repeated, with disdainful emphasis.

“O! there are many kinds of pride,” said Biddy, looking full at me and shaking her head; “pride is not all of one kind —”

“Well? What are you stopping for?” said I.

“Not all of one kind,” resumed Biddy. “He may be too proud to let any one take him out of a place that he is competent to fill, and fills well and with respect. To tell you the truth, I think he is; though it sounds bold in me to say so, for you must know him far better than I do.”

By the end of the novel, Pip has discovered the true worth of Joe and Biddy. Even the taint of crime and prison which Pip has been desperate to escape cannot hide Magwitch’s inner nobility, and Pip is able to ignore his social status as a criminal and offer him gratitude and succour. Pip has learned to trust his conscience and to a see the real worth of a person, irrespective of wealth, learning or social standing. He has discover that the Victorian idea of a ‘gentleman’ is built on sand.

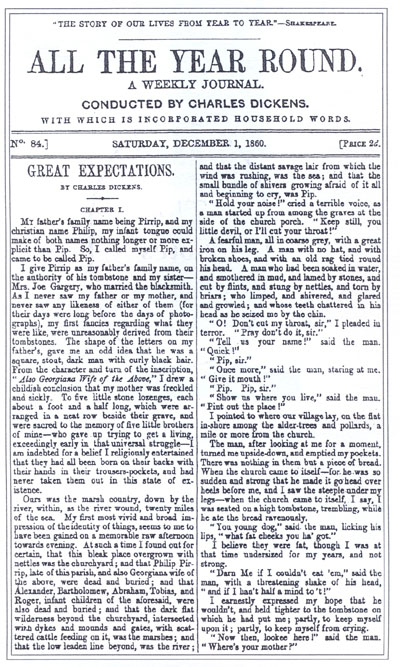

Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations was published in thirty-six weekly instalments in Dickens’s journal All the Year Round between 1860 and 1861. The first part appeared on December 1st 1860 (above).

I first saw David Lean’s atmospheric 1946 adaptation when it was shown by the film society at my grammar school (what is a good education worth!) And did I find that the pictures in my mind were from that film or Dickens’ novel? Well, the critic Roger Ebert writes:

Great Expectations’ has been called the greatest of all the Dickens films …[it] does what few movies based on great books can do: creates pictures on the screen that do not clash with the images already existing in our minds. Lean brings Dickens’ classic set-pieces to life as if he’d been reading over our shoulder: Pip’s encounter with the convict Magwitch in the churchyard, Pip’s first meeting with the mad Miss Havisham, and the ghoulish atmosphere in the law offices of Mr. Jaggers, whose walls are decorated with the death masks of clients he has lost to the gallows.

Certainly those were the images I had in my mind. The film is memorable for its opening sequence on the marshes, enhanced by beautiful black and white cinematography by Guy Green. In the TV version I had missed the scene where Miss Havisham, supported by Pip, marches around the table on which her mouldering wedding banquet is still laid out, stabbing each place setting with her stick. That’s in the film – and in the book, too:

“This,” said she, pointing to the long table with her stick, “is where I will be laid when I am dead. They shall come and look at me here.”

With some vague misgiving that she might get upon the table then and there and die at once, the complete realization of the ghastly waxwork at the Fair, I shrank under her touch.

“What do you think that is?” she asked me, again pointing with her stick; “that, where those cobwebs are?”

“I can’t guess what it is, ma’am.”

“It’s a great cake. A bride-cake. Mine!”

She looked all round the room in a glaring manner, and then said, leaning on me while her hand twitched my shoulder, “Come, come, come! Walk me, walk me!” […]

“Matthew will come and see me at last,” said Miss Havisham, sternly, when I am laid on that table. That will be his place,— there,” striking the table with her stick, “at my head! And yours will be there! And your husband’s there! And Sarah Pocket’s there! And Georgiana’s there! Now you all know where to take your stations when you come to feast upon me. And now go!”

At the mention of each name, she had struck the table with her stick in a new place. She now said, “Walk me, walk me!” and we went on again.

The best of Lean’s film is in the first hour, but later on the film takes great liberties with the story with, for example, Estella never marrying the odious Drummle, Miss Havisham’s death occurring much earlier, and culminating in a happy ending quite different even to Dickens’ revised version.

This is the opening sequence of David Lean’s film:

‘Which I mean to say, Pip old chap. What larks!’

See also

- Great Expectations: on David Perdue’s Dickens web

- What are we Meant to Think of Pip?

- The Two Endings

- I Am Greatly Changed: poem by Richard Price