The Guardian has, this last few days, been running a series The Grapes of Wrath Revisited, a journey along the old Route 66 – following in the footsteps of the Joads, the central characters in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath who fled the Oklahoma dustbowl for California – to see whether the tragedy and despair witnessed in the Great Depression is a long-forgotten nightmare or a present-day reality still haunting Barack Obama’s America.

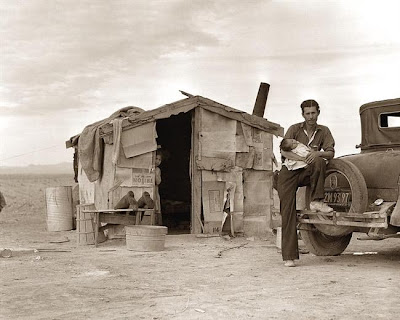

Four classic images from Dorothea Lange are a reminder of the circumstances that inspired Steinbeck’s novel:

The first article in the series began:

Seven decades later, the machine grinds on. It remains as faceless as back in the 1930s when John Steinbeck described the banks which forced Oklahoma’s destitute subsistence farmers from their land as institutions made by men but beyond their control.

“The banks were machines and masters all at the same time,” explains one of the land owners come to evict tenant farmers in the Grapes of Wrath. “The bank — the monster has to have profits all the time. It can’t stay one size… When the monster stops growing, it dies.”

The evictions set the fictional Joad family on a trek west to California that was the real experience of hundreds of thousands of Americans escaping drought and the towering clouds of soil carried on the wind across the midwestern dust bowl and from the mass unemployment of the great depression in northern cities. The road they flooded, Route 66 from Chicago to Los Angeles, later became a symbol of prosperity and the new found freedoms of the rock’n’roll era. But in the 1930s it played host to years of misery as destitute families, some on the brink of starvation, struggled along in search of work.

Then the poor looked to President Franklin Roosevelt as a shield from the excesses of capitalism and his New Deal to alleviate the worst hardship. Today, from Oklahoma to California, there is suspicion and outright hostility with even some of those who arguably have most to gain from liberal policies and social programmes speaking of all government as if it is the enemy.

The Joads began their journey just outside the small Oklahoma town of Sallisaw. Richard Mayo was 10 years old when Henry Fonda and the cast arrived in 1939 to make the film of the book. He said the townspeople resented the Grapes of Wrath for making Oklahomans appear ill-educated and backward.

“There was a lot of anger at the book, anger toward John Steinbeck: that’s not us, that’s not the way we are. I don’t think the anger subsided until the sixties. But there was a truth to the book”.

Each episode of the series has featured photo galleries (from which the images on this page are taken) and telling extracts from The Grapes of Wrath:

Highway 66 is the main migrant road. 66—the long concrete path across the country, waving gently up and down on the map, from Mississippi to Bakersfield—over the red lands and the gray lands, twisting up into the mountains, crossing the Divide and down into the bright and terrible desert, and across the desert to the mountains again, and into the rich California valleys.

66 is the path of a people in flight, refugees from dust and shrinking land, from the thunder of tractors and shrinking ownership, from the desert’s slow northward invasion, from the twisting winds that howl up out of Texas, from the floods that bring no richness to the kind and steel what little richness is there. From all of these the people are in flight, and they come into 66 from the tributary side roads, from the wagon tracks and the rutted country roads. 66 is the mother road, the road of flight…

The owners of the land came onto the land, or more often a spokesman for the owners came. They came in closed cars, and they felt the dry earth with their fingers and sometimes they drove big earth augers into the ground for soil tests. The tenants, from their sun-beaten dooryards, watched uneasily when the closed cars drove along the fields. And at last the owner men drove into the dooryards and sat in their cars to talk out of the windows. The tenant men stood beside the cars for a while, and then squatted on their hams and found sticks with which to mark the dust.

In the open doors the women stood looking out, and behind them the children—corn-headed children, with wide eyes, one bare foot on top of the other bare foot, and the toes working. The women and the children watched their men talking to the owner men. They were silent.

Some of the owner men were kind because they hated what they had to do. and some of them were angry because they hated to be cruel, and some of them were cold because they had long ago found that one could not be an owner unless one were cold. And all of them were caught in something larger than themselves…

The cars of the migrant people crawled out of the side roads onto the great cross-country highway, and then took the migrant way to the West. In the daylight they scuttled like bugs to the westward; and as the dark caught them, they clustered like bugs near to shelter and to water.

And because they were lonely and perplexed, because they had all come from a place of sadness and worry and defeat, and because they were all going to a new mysterious place, they huddled together; they talked together; they shared their lives, their food, and the things they hoped for in the new country. Thus it might be that one family camped near a spring, and another camped for the spring and for company, and a third because two families had pioneered the place and found it good. And when the sun went down, perhaps twenty families and twenty cars were there.

In the evening a strange thing happened: the twenty families became one family, the children were the children of all. The loss of home became one loss, and the golden time in the West was one dream...

And it came about that owners no longer worked on their farms. They farmed on paper; and they forgot the land, the smell, the feel of it, and remembered only that they owned it, remembered only what they gained and lost by it. And some of the farms grew so large that man could not even conceive of them any more, so large that it took batteries of book-keepers to keep track of interest and gain and loss; chemists to test the soil, to replenish; straw bosses to see that the stooping men were moving along the rows as swiftly as the material of their bodies could stand. Then such a farmer really became a storekeeper, and kept a store. He paid the men, and sold them food, and took the money back. And after a while he did not pay the men at all, and saved bookkeeping. These farms gave food on credit. A man might work and feed himself; and when the work was done, he might find that he owed money to the company. And the owners not only did not work the farms any more, many of them had never seen the farms they owned.

And then the dispossessed were drawn west—from Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico; from Nevada and Arkansas families, tribes, dusted out, tractored out. Carloads, caravans, homeless and hungry, twenty thousand and fifty thousand and a hundred thousand and two hundred thousand. They streamed over the mountains, hungry and restless – restless as ants, scurrying to find work to do – to lift, to push to pull, to pick, to cut – anything, any burden to bear, for food. The kids are hungry. We got no place to live. Like ants scurrying for work, for food and most of all for land…

There is a crime here that goes beyond denunciation. There is a sorrow here that weeping cannot symbolize. There is a failure here that topples all our success. The fertile earth, the straight tree rows, the sturdy trunks, and the ripe fruit. And children dying of pellagra must die because a profit cannot be taken from an orange. And coroners must fill in the certificates – died of malnutrition – because the food must rot, must be forced to rot.

The people come with nets to fish for potatoes in the river, and the guards hold them back; they come in rattling cars to get the dumped oranges, but the kerosene is sprayed. And they stand still and watch the potatoes float by, listen to the screaming pigs being killed in a ditch and covered with quicklime, watch the mountains of oranges slop down to a putrefying ooze; and in the eyes of the people there is the failure; and in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath. In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage…

And the great owners, who must lose their land in an upheaval, the great owners with access to history, with eyes to read history and to know the great fact: when property accumulates in too few hands it is taken away. And that companion fact: when a majority of the people are hungry and cold they will take by force what they need. And the little screaming fact that sounds through all history: repression works only to strengthen and knit the repressed…

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck was published in April 1939. The book and the film must, I think, have had a big impact on the development of my political outlook in my early teens. When it was published, Steinbeck’s novel had an enormous impact – it was widely read, debated and denounced by right-wing and business groups as communist propaganda. In 1962, the Nobel Prize committee cited The Grapes of Wrath as a ‘great work’ and as one of the key reasons for awarding Steinbeck the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The film version, starring Henry Fonda, was directed by John Ford in 1940. In the same year, Woody Guthrie composed his ballad, Tom Joad, which told the whole story in one song. In 1995, Bruce Springsteen’s The Ghost of Tom Joad incorporated lines from Tom Joad’s famous speech:

I’ll be all around in the dark. I’ll be everywhere, wherever you can look. Wherever there’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready and where people are eatin’ the stuff they raise and livin’ in the houses they build. I’ll be there, too.

NY Times Critics’ Picks: The Grapes of Wrath

Bruce Springsteen: The Ghost of Tom Joad

Men walkin’ ‘long the railroad tracks

Goin’ someplace there’s no goin’ back

Highway patrol choppers comin’ up over the ridge

Hot soup on a campfire under the bridge

Shelter line stretchin’ round the corner

Welcome to the new world order

Families sleepin’ in their cars in the southwest

No home no job no peace no rest

The highway is alive tonight

But nobody’s kiddin’ nobody about where it goes

I’m sittin’ down here in the campfire light

Searchin’ for the ghost of Tom Joad

He pulls prayer book out of his sleeping bag

Preacher lights up a butt and takes a drag

Waitin’ for when the last shall be first and the first shall be last

In a cardboard box ‘neath the underpass

Got a one-way ticket to the promised land

You got a hole in your belly and gun in your hand

Sleeping on a pillow of solid rock

Bathin’ in the city aqueduct

The highway is alive tonight

But where it’s headed everybody knows

I’m sittin’ down here in the campfire light

Waitin’ on the ghost of Tom Joad

Now Tom said “Mom, wherever there’s a cop beatin’ a guy

Wherever a hungry newborn baby cries

Where there’s a fight ‘gainst the blood and hatred in the air

Look for me Mom I’ll be there

Wherever there’s somebody fightin’ for a place to stand

Or decent job or a helpin’ hand

Wherever somebody’s strugglin’ to be free

Look in their eyes Mom you’ll see me.

Magnificent items from you, man. I’ve consider your stuff previous to and you are simply too fantastic. I actually like what you’ve received here, really like what you’re saying and the way in which in which you assert it. You are making it entertaining and you continue to take care of to keep it smart. I cant wait to read much more from you. That is really a terrific website.

Made my day! I am on Route 66 today……!

Geoff Fernandes

Oct 9.2012