I have celebrated writing by Rebecca Solnit many times on this blog. In this post I’m reproducing in its entirety ‘Protest and persist: why giving up hope is not an option’, today’s Guardian long read. Because it is a magnificent essay, one of her best pieces. Every paragraph burns with passion and sings like poetry. The Guardian’s strapline reads: ‘The true impact of activism may not be felt for a generation. That alone is reason to fight, rather than surrender to despair.’ Read on and find inspiration in these troubled times. Continue reading “Protest and persist: why giving up hope is not an option, by Rebecca Solnit”

Tag: Rebecca Solnit

After 46 years, recognition for a moment in which we can take genuine pride

A long, long time ago – 46 years to be precise – along with some 300 other students I took part in an anti-apartheid protest at Liverpool University, occupying the university’s administration building for 10 days in the spring term of 1970. The key demands we were making on the university was for the resignation of the Vice-Chancellor, Lord Salisbury, a supporter of the apartheid regimes in Rhodesia and South Africa, and for the university to divest itself of its investments in the the apartheid regime in South Africa. There were many sit-ins at British universities in this period, but in Liverpool it led to the severest disciplinary action of the time. Nine students, including Jon Snow, Channel 4 News presenter, were suspended for two years. But one, Peter Cresswell, was permanently expelled.

Yesterday, in an emotional ceremony following two decades of lobbying for restitution, Pete Cresswell, now aged 68 and retired from a career in social work, was at last awarded an honorary degree. His expulsion was finally recognised by those who spoke for the University as an injustice. As Pete observed in his acceptance speech, time had shown the protestors to be ‘on the right side of history’. Continue reading “After 46 years, recognition for a moment in which we can take genuine pride”

Fascism arrives as your friend: important words from a fellow-blogger

For the second time today I’m re-blogging a post by another blogger. Compared to the first, this one is deadly serious. From Cath’s Passing Time here are some things which must be said on the day that Jo Cox’s murderer is sentenced to life. Continue reading “Fascism arrives as your friend: important words from a fellow-blogger”

Holding on to Hope in the Dark after Trump

So now we know what it felt like to be alive when Hitler came to power. That was my first reaction to hearing of Donald Trump’s devastating victory in the U.S. Presidential election. As Martin Luther King wrote in his letter from his jail cell in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, ‘Never forget that everything Hitler did in Germany was legal.’ Coming after the Brexit vote, Trump’s win induces feelings of total despair. Can we find any hope on this dark day? Continue reading “Holding on to Hope in the Dark after Trump”

A roomful of apricots, the heart of a dog and moths that drink the tears of sleeping birds

As the daylight hours shorten and the leaves start to fall I think back to the beginning of this summer when our dog very nearly died. It’s a memory brought into sharp focus by a recently-watched film and the book I am reading at the moment. Laurie Anderson’s essay-film Heart of a Dog has a lot in common with Rebecca Solnit’s most recent book, The Faraway Nearby: both are digressive, looping, meandering disquisitions on storytelling and memory, and the connection between love and death. Continue reading “A roomful of apricots, the heart of a dog and moths that drink the tears of sleeping birds”

This bitter earth: the campaign to stop Shell’s Arctic catastrophe

A superb long read in the Guardian today by Rebecca Solnit describing a week-long expedition she took at the end of June through the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It’s a timely piece, as Charlotte Church and other Greenpeace protesters have been gathered for days outside Shell’s headquarters in London along with musicians performing a Requiem for Arctic Ice (inspired by the string quartet who continued to play as the Titanic went down) in an effort to persuade the company to abandon plans to drill for oil in the Arctic. Continue reading “This bitter earth: the campaign to stop Shell’s Arctic catastrophe”

Walking the Sandstone trail: three characters in conversation

In her book, Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Rebecca Solnit characterizes walking as, ‘a state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned, as though they were three characters finally in conversation together, three notes suddenly making a chord’. Solnit’s ‘three characters in conversation together’ describes pretty well the walk which saw (more or less) the completion of a project my good friend Bernie and I embarked upon many moons ago – to walk the length of the Sandstone Trail through Cheshire. We were accompanied on this leg of the journey by Tommy, a freshly-retired former work colleague. Our aim was to pick up where Bernie and I left off nearly a year ago and walk the final 16 mile hike that begins with most dramatic section of the Trail before it ends with a sigh, winding its way across the fields and meadows of the Cheshire – Shropshire border, then joining the Lllangollen canal for the last lap into Whitchurch.

Tommy and Bernie stride out

After leaving a car at either end of the hike (rural bus services being virtually extinct in this neck of the woods), we set off from the Pheasant Inn at Higher Buwardsley up Hill Lane, an ancient packhorse route and salters’ way – a short cut over the sandstone ridge linking the Cheshire salt-mining towns of Northwich, Middlewich and Nantwich with the old crossing-points over the Dee to Wales at Farndon and Chester. Salt was a very important commodity at the time, used not only as flavouring but, more crucially in pre-refrigeration times, for the preservation of perishable goods such as meat.

Hill Lane is only one of many such ancient paths and lanes which the Sandstone Trail now follows, a reminder of the importance of these trails in times past, worn by walking feet and the hooves of cattle and horses. As the Scottish poet Thomas A. Clark observes in In Praise of Walking, ‘always, everywhere, people have walked, veining the earth with

paths’:

Walking is the human way of getting about.

Always, everywhere, people have walked, veining the earth with

paths, visible and invisible, symmetrical and meandering.

There are walks in which we tread in the footsteps of others,

walks on which we strike out entirely for ourselves.

A journey implies a destination, so many miles to be consumed,

while a walk is its own measure, complete at every point along

the way.

We press on, treading ‘in the footsteps of others’, and soon reach the spine of the sandstone ridge that rises out of the Cheshire plain. Here, at the southern edge of Peckforton Hill, we pass the Lodge, a picturesque sandstone gatehouse belonging to the Peckforton Estate.

Peckforton Lodge

Peckforton Lodge is a reminder of the days when a monied man could buy up an extensive tract of land, with two villages thrown in: both Peckforton and nearby Beeston were part of an estate purchased by John Tollemache, 1st Baron Tollemache, in 1840. Between 1844 and 1850, Lord Tollemache had Peckforton Castle, a Victorian replica of a medieval castle, built from sandstone dug from a ridge-top quarry, now lost among the trees on the Peckforton Hills.

Local quarries exist all along the Trail, where sandstone was cut to provide building stone for houses, farm buildings and walls throughout this part of Cheshire. I feel at home on sandstone. It is the rock that reared up from the Cheshire plain at Alderley Edge, a few miles from where I grew up, and also the familiar bedrock of the place where I have lived these last fifty years: a city rose-red as Petra, Liverpool was founded on a sandstone bluff at the northern end of the ridge of sandstone which ruptures the Cheshire plain, and along which we now walk.

Bulkeley Hill (photo: Wikipedia)

Following the ridge the Trail leads to Bulkeley Hill, where the National Trust maintains a stretch of ancient woodland.

Bulkeley Hill

The name Bulkeley is first recorded as Bulceleia in 1086 and is from Old English bulluc and leah, meaning ‘pasture where bullocks graze’, suggesting that this was common land to which local villagers would bring their animals to graze. Thinking back, I remember that the primary school I attended, about ten miles or so from here, was on Bulkeley Road

Name Rock viewpoint

There’s a popular viewpoint, up here on Bulkeley Hill, from which on a clear day it’s possible to look west and see the Welsh hills. But not today. Warm and dry it may be – weather we’ve enjoyed since the beginning of September – but, as luck would have it, today, after two days of azure skies, it’s cloudy and dull, the distant hills shrouded in haze.

Through sandstone to Rawhead

So, no sight of the Welsh hills today as we make our way along the steep western escarpment towards Rawhead, the highest point on the Trail where we might have expected panoramic views. Still, we found plenty talk about, we three ‘characters in conversation’. The Scottish referendum was good for a mile or so, and provoked some pretty intense debate. (For myself, I’ve felt for some time that a Yes vote could be liberating for other places – like Liverpool – remote from Westminster and chafing under merciless policies they have not chosen.)

The murky view from Rawhead

Walking also led us to ponder the distances walked by individuals before the motor car arrived. I have been re-reading David Copperfield in which Copperfield (like Dickens himself) walks considerable distances as a matter of course. There is, for instance, a period in which, by day, he works as a legal clerk in central London, then walks out to Highgate to assist Doctor Strong with his dictionary project before walking to Putney to spend time with his fiancée, Dora, then back to his home near St Paul’s. On another occasion he walks the 16 miles from Dover to Canterbury, arriving at his destination in time for breakfast.

Then there’s the early chapter in Wuthering Heights where Mr Earnshaw walks from Haworth to Liverpool and back – 60 miles each way – staggering into the kitchen at Wuthering Heights at 11 pm on the third day. But, as Rebecca Solnit described in Wanderlust, William Wordsworth beat that with an amazing walk in 1790 when, with fellow-student Robert Jones, he walked across France, over the Alps and into Italy before arriving at Lake Como in Switzerland. They had covered a steady 30 miles a day.

That morning I’d read a review of Naomi Klein’s new book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs The Climate, in which she argues that the climate crisis is fundamentally not about carbon levels in the atmosphere, but about the extreme anti-regulatory version of capitalism that has seized global economies since the 1980s and has set us on a course of destruction and deepening inequality – that ‘our economic system’ is at war with life on Earth. Epic walker Wordsworth also had things to say about materialism and losing touch with nature or ‘getting and spending’ as he expressed it in his poem, ‘The World Is Too Much With Us’:

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;—

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not. Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

Rawhead triangulation point: the highest point on the Trail

Beyond Rawhead the path follows a precipitous course along the edge of sheer sandstone cliffs, before dropping down off the ridge to cross the busy A534 Wrexham-Nantwich road (also known as Salters Lane, so we know what the traffic would mainly have consisted of two to three hundred years ago).

Sandstone cliffs at Rawhead (photo: Wikipedia)

At Bickerton women were decorating the church porch and gateway with astonishingly intricate plaits of white flowers: a wedding, or maybe harvest festival, in preparation, perhaps? It looked like a scene from another time; I wish I’d taken a photo.

Holy Trinity Church, Bickerton (photo: Les Needham)

Past the church we headed up the lane and back onto the ridge. This is Bickerton Hill, owned and managed by the National Trust, a geological SSSI for its exposed Triassic sandstones, and a rich mixture of open woodland and lowland heath. Beneath the scattered birches, purple heather was in bloom, there were bright splashes of yellow gorse, and we tasted jet-black bilberries.

Bickerton Hill is one of few remaining areas of heathland in Cheshire, but it hasn’t always been so: the abandonment of grazing in the 1930s allowed birch, pine and oak to grow, shading out the bilberry and heather that had flourished for centuries. But, for a decade now the National Trust has been working to remove the encroaching trees and restore areas of the hill to heathland. Grazing has been reintroduced to halt the spread of the birch trees which have threatened the rare heathland habitat on the hill.

Bickerton Hill: birch, purple heather and bilberries

There were toadstools, too – the iconic ones, bright red with white markings, and familiar from childhood story books. Fly Agaric they’re called, apparently a reference to their use as an insecticide, crushed in milk to attract and kill flies. They also have hallucinogenic properties, and there is a long history of their use in religious and shamanistic rituals across northern Europe.

Fly Agaric: hallucinogenic if consumed

This was where we paused for lunch, with me handing round tomatoes fresh from from the greenhouse on our allotment. (What a summer it’s been for growing: we’re currently overwhelmed with tomatoes, and courgettes that seem to grow as soon as you turn your back. This week we have gathered the first figs from a tree we planted three years ago.)

Taking in the view

We sit on a log and take in the stunning views across the plain towards the Welsh hills. The haze is lifting a little and some sun breaks through, brightening the scene.

My eyes already touch the sunny hill.

going far ahead of the road I have begun.

So we are grasped by what we cannot grasp;

it has inner light, even from a distance-

and charges us, even if we do not reach it,

into something else, which, hardly sensing it,

we already are; a gesture waves us on

answering our own wave…

but what we feel is the wind in our faces.

– ‘A Walk’ by Rainer Maria Rilke

The view from Bickerton Hill

It’s difficult to believe, looking out at the tranquil rural view, that this was once a mining district. But, as at Alderley Edge, further to the north and a few miles from the village where I grew up, the vein of copper that runs along the sandstone ridge was mined beneath the Bickerton Hills from the 17th century onwards. Nearby is an engine house chimney, all that remains of mine buildings demolished in the 1930s.

Up here on Bickerton Hill there is older evidence of human intervention in the landscape. The Sandstone Trail crosses the ramparts of Iron Age Maiden Castle, one of a series of six forts on the sandstone ridge – hilltop sites probably first enclosed in the Neolithic, around 6,000 years ago, to mark them out as special places. By the late Bronze and early Iron Age these hilltop enclosures had become increasingly defensive, possibly to protect and regulate important goods such as salt, grain and livestock.

Packing away the remnants of our lunch, we press on – past the memorial called Kitty’s Stone; placed at the highest point of the hill, it was placed here by Leslie Wheeldon, the benefactor who helped the National Trust acquire the hilltop heathland, and displays poems written by him in memory of his wife, Kitty.

Down off the ridge and through Cheshire farmland

The Trail drops down through Hether Wood to emerge at the end of southern end of the sandstone ridge, close to Larkton Hall Farm. Now we are walking through a classic Cheshire landscape of undulating meadows and hedges, the fields grazed by the black and white cows that seem as much part of the landscape here as the grass and the trees.

Undulating meadows – and a lone hawthorn

Manor House Stables with Bickerton Hill beyond

We pass Manor House Stables with its extensive white-railed training course. Tommy, who ‘laid his first bet when he was five’, fills us in on the details. It’s operated by Tom Dascombe, who is gaining a reputation in the racehorse training world, and owned by Michael Owen, the former Liverpool and Manchester United footballer. It’s a multi-million pound investment and looked it: new buildings that appeared to house luxurious reception facilities for humans, as well as, apparently, state-of-the-art facilities for the horses, including an equine pool, ice bath and veterinary centre

Through the fields

Now the Trail took us through fields, some where maize had been freshly-sown, some golden with the stalks of recently-harvested grain. At Bickley Hall Farm, belonging to the Cheshire Wildlife Trust, we encountered a herd of pretty fearsome-looking (but docile) longhorn cows, part of the Trust’s herd of Longhorn and Dexter cattle, and Hebridean and Shropshire sheep. The Longhorns are the Trust’s ‘living lawnmowers’, a natural way of managing wildflower meadows, heathlands and peatbogs for the benefit of wildlife.

Bickley Hall Farm Longhorns (photo: Tom Marshall)

The winding path

‘The traveller that resolutely follows a rough and winding path will sooner reach the end of his journey than he that is always changing his direction, and wastes the hour of daylight in looking for smoother ground and shorter passages.’ That was the view of Samuel Johnson, and he was surely right. It was late in the afternoon and, as the Trail wound its way across one field after another, at each hedge or stile we hoped to see the long-anticipated Llangollen canal which would signify the final leg of our journey.

Willeymoor lock – and the landlady’s bridge

Then, over a stile and long a hedged path, suddenly we were there on the canal side, at Willeymoor Lock, one of those greatly-anticipated stages of a canal journey where a pub invites a pause. Certainly, for several miles now, what I had been imagining was a significant pause at the waterside with a pint of good beer. But the pub was closed – it would open again at 6pm.

Taking advantage of the outside seating, we nevertheless sat and rested our feet. This is the Llangollen canal, a branch of the Shropshire Union, that runs for 46 miles between Hurleston on the SU and the river Dee above Llangollen. As we sat, the pub landlady appeared and explained in a matter of fact manner that she had run the pub for more than thirty years and felt entitled to a break in the afternoons.

We fell into conversation, and she explained that for several years after taking over the pub she had been unable to cross to the far side of the canal via the lock gates, suffering from a degree of vertigo even more serious than mine. So she had her own bridge built, offering easy access to the far bank and the A49. But then she discovered that British Waterways was entitled to make an annual charge for the convenience!

Navigating the lock

By this stage we had realised that we couldn’t walk the last threee miles into Whitchurch since one of our party had acquired fairly painful blisters. While we waited for a taxi, a barge appeared, navigated by a couple, and we watched (the way you do) as the Canadian half of the crew manipulated the key that opened the lock gates while her partner steered the craft into the lock.

Then it was a brief taxi ride back to our waiting car in Whitchurch, and a surprisingly lengthy drive (had we really walked all that way?) back to our staring point, the Pheasant Inn at Buwardsley. Now, sitting on the pub’s terrace looking out across the Cheshire plain as the clouds lifted sun finally broke through, I was able to savour an excellent local beer – a pint of Weetwood’s Best Bitter, brewed not far away in Tarporley.

Later, driving back towards Liverpool, the western sun shone golden on the ridge of hills we had walked that day. And I thought about the pleasure of walking – something captured in the words of a poem by Thomas Traherne, a 17th century mystic and contemporary of Milton. Born about the year 1636, probably at Hereford, Traherne was the son of a poor shoemaker, and – according to his biographer Gladys Wade, was a happy man:

In the middle of the 17th Century, there walked the muddy lanes of Herefordshire and the cobbled streets of London, a man who had found the secret of happiness. He lived through a period of bitterest, most brutal warfare and a period of corrupt and disillusioned peace. He saw the war and the peace at close quarters. He suffered as only the sensitive can. He did not win his felicity easily. Like the merchantman seeking goodly pearls or the seeker for hidden treasure in a field, he paid the full price. But he achieved his pearl, his treasure. He became one of the most radiantly, most infectiously happy mortals this earth has known.

Most of his poetry is mystical and religious, but in ‘Walking’ he wrote a paean to the secular act of walking

To walk abroad is, not with eyes,

But thoughts, the fields to see and prize;

Else may the silent feet,

Like logs of wood,

Move up and down, and see no good

Nor joy nor glory meet.

Ev’n carts and wheels their place do change,

But cannot see, though very strange

The glory that is by;

Dead puppets may

Move in the bright and glorious day,

Yet not behold the sky.

And are not men than they more blind,

Who having eyes yet never find

The bliss in which they move;

Like statues dead

They up and down are carried

Yet never see nor love.

To walk is by a thought to go;

To move in spirit to and fro;

To mind the good we see;

To taste the sweet;

Observing all the things we meet

How choice and rich they be.

To note the beauty of the day,

And golden fields of corn survey;

Admire each pretty flow’r

With its sweet smell;

To praise their Maker, and to tell

The marks of his great pow’r.

To fly abroad like active bees,

Among the hedges and the trees,

To cull the dew that lies

On ev’ry blade,

From ev’ry blossom; till we lade

Our minds, as they their thighs.

Observe those rich and glorious things,

The rivers, meadows, woods, and springs,

The fructifying sun;

To note from far

The rising of each twinkling star

For us his race to run.

A little child these well perceives,

Who, tumbling in green grass and leaves,

May rich as kings be thought,

But there’s a sight

Which perfect manhood may delight,

To which we shall be brought.

While in those pleasant paths we talk,

’Tis that tow’rds which at last we walk;

For we may by degrees

Wisely proceed

Pleasures of love and praise to heed,

From viewing herbs and trees.

See also

Rebecca Solnit: ‘our privacy is being strip-mined and hoarded’

Rebecca Solnit has written an elegaic piece in the current London Review of Books that now and again also reveals a deep, yet controlled anger. The article (unfortunately only available online to subscribers) gives voice to a sense of loss felt, at least by those of us of a certain age, about the encroachment of the the internet, mobile phones and the various forms of instant communication that, in little more than a decade, have profoundly changed the way we live and relate to each other. She begins:

When I think about, say, 1995, or whenever the last moment was before most of us were on the internet and had mobile phones, it seems like a hundred years ago. Letters came once a day, predictably, in the hands of the postal carrier. News came in three flavours – radio, television, print – and at appointed hours. Some of us even had a newspaper delivered every morning. Those mail and newspaper deliveries punctuated the day like church bells. You read the paper over breakfast. If there were developments you heard about them on the evening news or in the next day’s paper. You listened to the news when it was broadcast, since there was no other way to hear it. A great many people relied on the same sources of news, so when they discussed current events they did it under the overarching sky of the same general reality. Time passed in fairly large units, or at least not in milliseconds and constant updates.

While previous technologies have expanded communication, those that have exploded into our lives since the 1990s may be contracting it, Solnit argues:

The eloquence of letters has turned into the unnuanced spareness of texts; the intimacy of phone conversations has turned into the missed signals of mobile phone chat. I think of that lost world, the way we lived before these new networking technologies, as having two poles: solitude and communion. The new chatter puts us somewhere in between, assuaging fears of being alone without risking real connection. It is a shallow between two deep zones, a safe spot between the dangers of contact with ourselves, with others.

I live in the heart of it, and it’s normal to walk through a crowd – on a train, or a group of young people waiting to eat in a restaurant – in which everyone is staring at the tiny screens in their hands. It seems less likely that each of the kids waiting for the table for eight has an urgent matter at hand than that this is the habitual orientation of their consciousness. At times I feel as though I’m in a bad science fiction movie where everyone takes orders from tiny boxes that link them to alien overlords. Which is what corporations are anyway, and mobile phones decoupled from corporations are not exactly common.

For Solnit, these changes have brought a profound a sense of loss ‘for a quality of time we no longer have, and that is hard to name and harder to imagine reclaiming’:

My time does not come in large, focused blocks, but in fragments and shards. The fault is my own, arguably, but it’s yours too – it’s the fault of everyone I know who rarely finds herself or himself with uninterrupted hours. We’re shattered. We’re breaking up.

In previous essays, Solnit has written of how the new technologies brought good things: many people found expression free of censorship; instant communication facilitated political opposition (Facebook playing a part in the Arab Spring’s initial phase in 2011, Twitter in spreading the Occupy movement, while WikiLeaks grasped the opportunity to disseminate across the globe truths about how power is wielded). But now she feels a deep sense of unease:

We were not so monitored, because no one read our letters the way they read our emails to sell us stuff, as Gmail does, or track our communications as the NSA does. We are moving into a world of unaccountable and secretive corporations that manage all our communications and work hand in hand with governments to make us visible to them. Our privacy is being strip-mined and hoarded.

Moreover:

Between you and me stands a corporation every time we make contact – not just the post office or the phone company, but a titan that shares information with the National Security Administration – is dismaying. But that’s another subject: mine today is time.

The young, Solnit laments, ‘are disappearing down the rabbit hole of total immersion in the networked world, and struggling to get out of it’. Getting out of it is, she argues, will be about slowness, and about finding alternatives:

Alternatives to the alienation that accompanies a sweater knitted by a machine in a sweatshop in a country you know nothing about, or jam made by a giant corporation that has terrible environmental and labour practices and might be tied to the death of honeybees or the poisoning of farmworkers. It’s an attempt to put the world back together again, in its materials but also its time and labour. … Right now we need to articulate these subtle things, this richer, more expansive quality of time and attention and connection, to hold onto it. Can we? The alternative is grim, with a grimness that would be hard to explain to someone who’s distracted.

Solnit has argued the case for ‘slowness as an act of resistance’ before: in an essay published in Orion magazine in 2007 she wrote:

Ultimately, I believe that slowness is an act of resistance, not because slowness is a good in itself but because of all that it makes room for, the things that don’t get measured and can’t be bought.

The title of a collection of essays by Rebecca Solnit, published in 2008, was Storming the Gates of Paradise. Perhaps the time will come when we will need to storm the gates of the behemoths – Microsoft, Google, Apple, and the rest – that have dazzled us with their paradisal products.

Too Soon to Tell: Rebecca Solnit’s case for Hope, continued

I thought I’d pass on some inspiring thoughts from a new essay written by writer, environmental campaigner and global justice activist Rbecca Solnit (no stranger to these posts – see the links below). Ten years ago Rebecca Solnit began writing about hope with her online essay Acts of Hope, posted at Tomdispatch in May 2003, that bleak moment when it seemed that the huge antiwar demonstrations had failed as the Bush administration launched Shock and Awe in Iraq. Solnit says that the essay changed her life and her work, revealing how the Internet could give wings to words. What she wrote spread around the world, putting her in touch with people and movements, and led to deep conversations about the possible and the impossible.

Solnit’s message – developed in her book Hope In The Dark – might be summarized as a rebuttal of Alice’s assertion in Through the Looking Glass that ‘one can’t believe impossible things’. For Solnit that notion of the impossible represents the war being waged to inhibit our collective imagination. In that war every creative act, every thoughtful inquiry, every opening of a mind is a victory for hope. We may not be able to discern their results immediately, but somewhere down the line there will be consequences.

Each December since the publication of Hope In The Dark, Rebecca Solnit has written an end of year essay for Tomdispatch, and now she has published a new essay that updates the vision of that first one, written in dark times ten years ago, when she ‘tried to undermine despair with the case for hope’. In Too Soon to Tell: The Case for Hope, Continued, Solnit argues that a decade later, much has changed, and not necessarily for the better. But not entirely for the worse either:

If there is one thing we can draw from where we are now and where we were then, it’s that the unimaginable is ordinary, and the way forward is almost never a straight path you can glance down, but a labyrinth of surprises, gifts, and afflictions you prepare for by accepting your blind spots as well as your intuitions.

The nub of her philosophy is this:

If you take the long view, you’ll see how startlingly, how unexpectedly but regularly things change. Not by magic, but by the incremental effect of countless acts of courage, love, and commitment, the small drops that wear away stones and carve new landscapes, and sometimes by torrents of popular will that change the world suddenly. To say that is not to say that it will all come out fine in the end regardless. I’m just telling you that everything is in motion, and sometimes we are ourselves that movement.

Hope and history are sisters: one looks forward and one looks back, and they make the world spacious enough to move through freely. Obliviousness to the past and to the mutability of all things imprisons you in a shrunken present. Hopelessness often comes out of that amnesia, out of forgetting that everything is in motion, everything changes. We have a great deal of history of defeat, suffering, cruelty, and loss, and everyone should know it. But that’s not all we have.

There’s the people’s history, the counter-history that you didn’t necessarily get in school and don’t usually get on the news: the history of the battles we’ve won, of the rights we’ve gained, of the differences between then and now that those who live in forgetfulness lack. This is often the history of how individuals came together to produce that behemoth civil society, which stands astride nations and topples regimes — and mostly does it without weapons or armies. It’s a history that undermines most of what you’ve been told about authority and violence and your own powerlessness.

Civil society is our power, our joy, and our possibility, and it has written a lot of the history in the last few years, as well as the last half century. If you doubt our power, see how it terrifies those at the top, and remember that they fight it best by convincing us it doesn’t exist. It does exist, though, like lava beneath the earth, and when it erupts, the surface of the earth is remade.

Things change. And people sometimes have the power to make that happen, if and when they come together and act (and occasionally act alone, as did writers Rachel Carson and Harriet Beecher Stowe — or Mohammed Bouazizi, the young man whose suicide triggered the Arab Spring).

If you fix your eye on where we started out, you’ll see that we’ve come a long way by those means. If you look forward, you’ll see that we have a long way to go — and that sometimes we go backward when we forget that we fought for the eight-hour workday or workplace safety or women’s rights or voting rights or affordable education, forget that we won them, that they’re precious, and that we can lose them again. There’s much to be proud of, there’s much to mourn, there’s much yet to do, and the job of doing it is ours, a heavy gift to carry. And it’s made to be carried, by people who are unstoppable, who are movements, who are change itself.

Solnit doesn’t deny that at the present juncture, things look grim, with the Arab Spring stalled, the Occupy movement dissipated, and resistance in places like Greece and Spain fading. Then there’s climate change; as she was writing the essay:

The news just came in that we reached 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere, the highest level in more than five million years. This is terrible news on a scale that eclipses everything else, because it encompasses everything else. We are wrecking our world, for everyone for all time, or at least the next several thousand years.

The last time CO2 levels were so high was probably in the Pliocene epoch, between 3.2m and 5m years ago, when Earth’s climate was much warmer than today. But, argues Solnit, there are people ‘doing extraordinary things to save the world’:

For you, for us, for generations unborn, for species yet to be named, for the oceans and sub-Saharan Africans and Arctic dwellers and everyone in-between, for the whole unbearably beautiful symphony of life on Earth that is imperilled.

But Solnit is sustained by the memory that in 2003, there was no climate movement to speak of (at least in the United States). Now, she says, things have changed.

There’s a vibrant climate movement in North America. If you haven’t quite taken that in, it might be because it’s working on so many disparate fronts that are often treated separately: mountaintop coal removal, coal-fired power plants (closing 145 existing ones to date and preventing more than 150 planned ones from opening), fracking, oil exploration in the Arctic, the Tar Sands pipeline, and 350.org’s juggernaut of a campus campaign to promote disinvestment from oil, gas, and coal companies. Only started in November 2012, there are already divestment movements under way on more than 380 college and university campuses, and now cities are getting on board. It has significant victories; it will have more.

And though global climate agreements have proved feeble

Some countries – notably Germany, with Denmark not far behind – have done remarkable things when it comes to promoting non-fossil-fuel renewable energy. Copenhagen, for example, in the cold gray north, is on track to become a carbon-neutral city by 2025 (and in the meantime reduced its carbon emissions 25% between 2005 and 2011). The United States has a host of promising smaller projects. To offer just two examples, Los Angeles has committed to being coal-free by 2025, while San Francisco will offer its citizens electricity from 100% renewable and carbon-neutral sources and its supervisors just voted to divest the city’s fossil-fuel stocks.

And though Occupy may have faded from the news, it ‘began to say what needed to be said about greed and capitalism, exposing a brutality that had long been hushed up, revealing both the victims of debt and the rigged economy that created it’. Moreover, Occupy has morphed into ‘thousands of local gatherings and networks’ such as Occupy Sandy, still doing vital work in the destruction zone of that hurricane, and Strike Debt, a movement challenging ‘the immorality of the student, medical, and housing debt that is destroying so many lives’. She cites the xample, too, of Idle No More, the Canada-based movement of indigenous power and resistance to a Canadian government that has gone in for environmental destruction on a grand scale. Founded by four women in November 2012, it’s spread across North America, sparking environmental actions and new coalitions around environmental and climate issues.

Read the essay in full: it’s inspiring. This is how Rebecca Solnit sums up her message:

Here’s what I’m saying: you should wake up amazed every day of your life, because if I had told you in 1988 that, within three years, the Soviet satellite states would liberate themselves non-violently and the Soviet Union would cease to exist, you would have thought I was crazy. If I had told you in 1990 that South America was on its way to liberating itself and becoming a continent of progressive and democratic experiments, you would have considered me delusional. If, in November 2010, I had told you that, within months, the autocrat Hosni Mubarak, who had dominated Egypt since 1981, would be overthrown by 18 days of popular uprisings, or that the dictators of Tunisia and Libya would be ousted, all in the same year, you would have institutionalized me. If I told you on September 16, 2011, that a bunch of kids sitting in a park in lower Manhattan would rock the country, you’d say I was beyond delusional. You would have, if you believed as the despairing do, that the future is invariably going to look like the present, only more so. It won’t.

I still value hope, but I see it as only part of what’s required, a starting point. Think of it as the match but not the tinder or the blaze. To matter, to change the world, you also need devotion and will and you need to act. Hope is only where it begins, though I’ve also seen people toil on without regard to hope, to what they believe is possible. They live on principle and they gamble, and sometimes they even win, or sometimes the goal they were aiming for is reached long after their deaths. Still, it’s action that gets you there. When what was once hoped for is realized, it falls into the background, becomes the new normal; and we hope for or carp about something else.

The future is bigger than our imaginations. It’s unimaginable, and then it comes anyway. To meet it we need to keep going, to walk past what we can imagine. We need to be unstoppable. And here’s what it takes: you don’t stop walking to congratulate yourself; you don’t stop walking to wallow in despair; you don’t stop because your own life got too comfortable or too rough; you don’t stop because you won; you don’t stop because you lost. There’s more to win, more to lose, others who need you.

You don’t stop walking because there is no way forward. Of course there is no way. You walk the path into being, you make the way, and if you do it well, others can follow the route. You look backward to grasp the long history you’re moving forward from, the paths others have made, the road you came in on. You look forward to possibility. That’s what we mean by hope, and you look past it into the impossible and that doesn’t stop you either. But mostly you just walk, right foot, left foot, right foot, left foot. That’s what makes you unstoppable.

Rebecca Solnit: lecture on Hope, May 2011

See also

- Rebecca Solnit: What Comes After Hope: the new essay at TomDispatch

- Hope in the Dark

- Getting Lost: leave the door open for the unknown

- Acts of Hope: Challenging Empire on the World Stage (TomDispatch, May 2003)

- Rebecca Solnit’s Secret Library of Hope (TomDispatch)

- The Age of Mammals: Looking Back on the First Quarter of the Twenty-First Century (TomDispatch, December 2006)

- Compassion Is Our New Currency: Notes on 2011’s Preoccupied Hearts and Minds (TomDispatch, December 2011)

- The Sky’s the Limit: The Demanding Gifts of 2012 (TomDispatch, December 2012)

The right to roam land and shore, ‘but for the sky, no fences facing’

The other day I posted about how access to the river Mersey was restricted by the Cressington and Grassendale private estates. ‘As a freeborn Englishman’, I wrote, ‘I can’t understand the idea that a private estate should have the right to deny people access to a great river’. That provoked a fair amount of debate, so I thought I’d look at the question of the right of access and the notion of public space in a bit more detail, exploring how the struggle for common land and the right to wander where you will has reflected sharply-differing interpretations of the legal and moral meaning of private property. From the resistance to the enclosure of common lands to the hard-fought struggle for the right to roam, it’s a stirring story, and one that is far from over; new battle-lines are being drawn over access to the British coastline and its beaches, and the rapid privatisation of public space in our cities.

No man made the land, it is the original inheritance of the whole species. The land of every country belongs to the people of that country.

– John Stuart Mill, 1848

When you step back and take a historical view, what is clear is that access to the land has been a defining issue in British society for a thousand years. Rebecca Solnit, a writer thrilled by the extent of the English network of paths and rights of way compared to her native America, has nevertheless observed that in this country ‘accessing the land has been something of a class war’. For a thousand years, landowners have been sequestering more and more of the island for themselves, and for the past hundred and fifty, landless people have been fighting back.

For some, it’s all down to the Normans; conquering England in 1066, they embarked on a swift land grab, establishing huge deer parks for hunting (the nearest here being Toxteth Park and the hunting forest of Mara and Mondrum, now known as Delamere). Fierce penalties for poaching or in any way encroaching upon these hunting lands were visited upon the poor or landless in the centuries that followed – castration, deportation, execution (after 1723, for example, taking rabbits or fish, let alone deer, was an offence punishable by death).

The deer parks were gouged from the commons: lands which might be (usually were) privately owned, but on which locals retained rights to gather wood and graze animals – and to follow their noses. Over time a principle had been established in common law: that the public had the right to walk no matter whose property they traversed, following rights-of-way-footpaths across the fields and woods that were necessary for work and travel.

There’s a proud tradition of English folk rising up to resist the trashing of these entitlements by the rich and powerful, and it stretches back a long way. Between 1509 and 1640 there were more than three hundred riots in England, many of them sparked off by the enclosure of common land or the denial of customary rights of pasture. Some were large enough to be regarded as risings or rebellions; others were small and insignificant, a handful of villagers levelling someone’s hedges and letting their cattle in.

The Norfolk Rising of 1549 began as a local demonstration against the enclosure of common land, but quickly developed into a revolt against the whole system of enclosures. It is considered, after the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, the most significant of all the peasant risings. In an organized response to the general oppression of the poor, 16,000 rebels attacked and took possession of Norwich, then the second city of the kingdom, and for three weeks administered the district until attacked and defeated by a government army. This is how a chronicler at the time reported the sense of injustice felt by those who rose up:

For, said they, the pride of great men is now intolerable, but their condition miserable. These abound in delights and compassed with the fullness of all things, and consumed with vain pleasure, thirst only after gain, and are inflamed with the burning delights of their desires: but themselves almost killed with labour and watching, do nothing all their life long but sweat, mourn, hunger and thirst . . .

The common pastures left by our predecessors for the relief of us and our children are taken away. The lands which in the memory of our fathers were common, those are ditched and hedged in, and made several. The pastures are enclosed, and we shut out: whatsoever fowls of the air, or fishes of the water, and increase of the earth, all these they devour, consume and swallow up; yea, nature doth not suffice to satisfy their lusts …

Shall they, as they have brought hedges against common pastures, inclose with their intolerable lusts also, all the commodities and pleasure of this life, which Nature the parent of us all, would have common, and bringeth forth every day for us, as well as for them? We can no longer bear so much, so great and so cruel injury, neither can we with quiet minds behold so great covetousness, excess and pride of the nobility; we will rather take arms, and mix heaven and earth together, than endure so great cruelty. Nature hath provided for us, as well as for them; hath given us a body and a soul, and hath not envied us other things. While we have the same form, and the same condition of birth together with them, why should they have a life so unlike to ours, and differ so far from us in calling?

We desire liberty, and an indifferent [equal] use of all things: this we will have, otherwise these tumults and our lives shall end together.

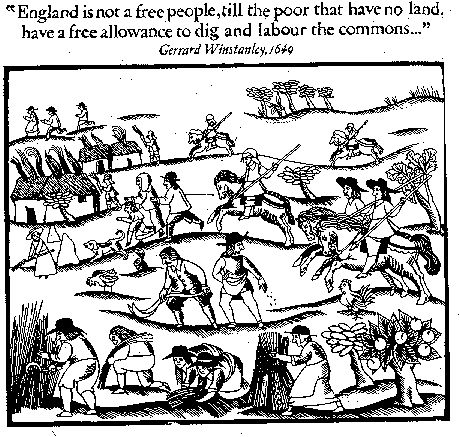

In the Putney debates of 1647, the Leveller Colonel Rainborough argued that, ‘the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live as the richest he’; two years later, on 1 April 1649, Gerrard Winstanley (who hailed from Wigan) and his fellow diggers started cultivating land on St George’s Hill, Surrey, and proclaimed a free Commonwealth.

We come in peace, they said

To dig and sow

We come to work the land in common

And to make the waste land grow

This earth divided

We will make whole

So it can be

A common treasury for all.

The sin of property

We do disdain

No one has any right to buy and sell

The earth for private gain

By theft and murder

They took the land

Now everywhere the walls

Rise up at their command.

– Leon Rosselson, ‘World Turned Upside Down’

In their first manifesto the Diggers asserted:

The earth (which was made to be a Common Treasury of relief for all, both Beasts and Men) was hedged into Inclosures by the teachers and rulers, and the others were made Servants and Slaves. … Take note that England is not a Free people, till the Poor that have no Land, have a free allowance to dig and labour the Commons, and so live as Comfortably as the Landlords that live in their Inclosures.

As well as joining in the collective labour on the occupied land at St Georges Hill, Winstanley wrote pamphlets defending the Diggers’ cause. This was not just a local matter, but a national issue. The traditional village was breaking up under the pressures of an emerging capitalist market. Richer farmers were beginning to produce for the market, employing the labour of villagers who had been evicted from their smallholdings and become dependent on wages. Yet, Winstanley (whose proto-socialist argument was couched in religious terms, as most debates were at the time) pointed out, one third of England was uncultivated wasteland – barren while children starved:

Let all men say what they will, so long as such are Rulers as call the Land theirs, upholding this particular propriety of Mine and Thine; the common-people shall never have their liberty, nor the Land ever [be] freed from troubles, oppressions and complainings. O thou proud selfish governing Adam, in this land called England! Know that the cries of the poor, whom thou layeth heavy oppressions upon, is heard. […]

Therefore you dust of the earth, that are trod under foot, you poor people, that makes both scholars and rich men your oppressors by your labours, take notice of your privilege, the Law of Righteousnesse is now declared. All the men and women in England, are all children of this Land, and the earth is the Lord’s, not particular men’s that claims a proper interest in it above others, which is the devil’s power. This is my Land …

Therefore if the rich will still hold fast this propriety of Mine and Thine, let them labour their own land with their own hands. And let the common-people … labour together, and eat bread together upon the Commons, Mountains, and Hills. For as the enclosures are called such a man’s Land, and such a man’s Land; so the Commons and Heath, are called the common-people’s, and let the world see who labours the earth in righteousnesse, and . . . let them be the people that shall inherit the earth. …Was the earth made for to preserve a few covetous, proud men, to live at ease, and for them to bag and barn up the treasures of the earth from others, that they might beg or starve in a fruitful Land, or was it made to preserve all her children?

The Diggers’ occupation of the land on St Georges Hill lasted only five months before they local landowners went to court to have them evicted. In 1649, St George’s Hill was a stretch of wasteland. Today, ironically, it is an exclusive gated private estate, with multi-million pound mansions, golf course and private tennis courts. In 1995 and 1999 The Land is Ours, the group founded by George Monbiot, organised a mass trespass there in order to dramatise the issues of open access to the countryside of how the land is used.

In Scotland, common land was abolished in 1695, while in England enclosure acts and unauthorized but fiercely enforced seizures of hitherto common land accelerated in the eighteenth century. Between 1760 and 1870, about 7 million acres (about one sixth the area of England) were changed by Acts of Parliament from common land to enclosed land. In Das Kapital, Marx described how, from the 15th century to 19th century, ‘the systematic theft of communal property was of great assistance in swelling large farms and in ‘setting free’ the agricultural population as a proletariat for the needs of industry’.

Many did indeed see the process as a war; in 1803, the President of the Board of Agriculture, writing at the height of the Napoleonic Wars, saw the colonization of the commons around London as a patriotic duty:

Let us not be satisfied with the liberation of Egypt or the subjugation of Malta, but let us subdue Finchley Common, let us conquer Hounslow Heath; let us compel Epping Forest to submit to the yoke of improvement.

North of the border, in the Clearances, thousands of Highlanders were evicted from their holdings and shipped off to Canada, or forced to seek work as wage labourers in the industrial towns as landowners turned their estates over to profitable sheep farming. Some cottagers were literally burnt out of house and home by the agents of the Lairds. Betsy Mackay, who was sixteen when her family was evicted from the Duke of Sutherland’s estates, gave this account of their eviction:

Our family was very reluctant to leave and stayed for some time, but the burning party came round and set fire to our house at both ends, reducing to ashes whatever remained within the walls. The people had to escape for their lives, some of them losing all their clothes except what they had on their back. The people were told they could go where they liked, provided they did not encumber the land that was by rights their own. The people were driven away like dogs.

In England, as E.P. Thompson wrote in The Making of the English Working Class,’the years between 1760 and 1820 are the years of wholesale enclosure in which, in village after village, common rights are lost. … Enclosure (when all the sophistications are allowed for) was a plain enough case of class robbery’. In 1809, when John Clare was 16, an Enclosure Act was passed to enclose lands in the parish of Helpstone in Northamptonshire and in neighbouring parishes. This was the land where he had been raised, and it formed his world, his horizon:

Nor fence of ownership crept in between

To hide the prospect of the following eye

Its only bondage was the circling sky

– John Clare, from The Moors, 1824

The central aim of enclosure was to increase profits, but the price of ‘Improvement’ was the loss of the commons and waste grounds, which according to the Act ‘yield but little Profit’:

Now this sweet vision of my boyish hours

Free as spring clouds and wild as summer flowers

Is faded all – a hope that blossomed free,

And hath been once, no more shall ever be

Inclosure came and trampled on the grave

Of labour’s rights and left the poor a slave

And memory’s pride ere want to wealth did bow

Is both the shadow and the substance now

– John Clare, from The Moors, 1824

Clare was devastated by this violation of his natural and social environment. For Clare, the open-field system fostered a sense of community, the fields spread out in a wheel with the village at its hub. Fences, gates and ‘no trespassing’ signs went up. Trees were felled and streams diverted so that ditches could follow a straight line:

There once was lanes in natures freedom dropt

There once was paths that every valley wound

Inclosure came & every path was stopt

Each tyrant fixt his sign where pads was found

To hint a trespass now who crossd the ground

Justice is made to speak as they command

The high road now must be each stinted bound

–Inclosure thourt a curse upon the land

& tastless was the wretch who thy existence pland

– John Clare, from ‘The Village Minstrel’, 1821

George Monbiot, writing in The Guardian in July 2012, observed how, as Clare moved from his teens to his thirties, acts of enclosure granted the local landowners permission to fence the fields, the heaths and woods, excluding the people who had worked and played in them. For Clare, everything he sees falls apart:

Almost everything Clare loved was torn away. The ancient trees were felled, the scrub and furze were cleared, the rivers were canalised, the marshes drained, the natural curves of the land straightened and squared. Farming became more profitable, but many of the people of Helpston – especially those who depended on the commons for their survival – were deprived of their living. The places in which the people held their ceremonies and celebrated the passing of the seasons were fenced off. The community, like the land, was parcelled up, rationalised, atomised. I have watched the same process breaking up the Maasai of east Africa. […]

What Clare suffered was the fate of indigenous peoples torn from their land and belonging everywhere. His identity crisis, descent into mental agony and alcohol abuse, are familiar blights in reservations and outback shanties the world over. His loss was surely enough to drive almost anyone mad; our loss surely enough to drive us all a little mad.

For while economic rationalisation and growth have helped to deliver us from a remarkable range of ills, they have also torn us from our moorings, atomised and alienated us, sent us out, each in his different way, to seek our own identities. We have gained unimagined freedoms, we have lost unimagined freedoms – a paradox Clare explores in his wonderful poem ‘The Fallen Elm‘. Our environmental crisis could be said to have begun with the enclosures. The current era of greed, privatisation and the seizure of public assets was foreshadowed by them: they prepared the soil for these toxic crops.

In John Clare: A Biography, Jonathan Bate follows E.P. Thompson in describing Clare as a poet of ‘ecological protest’, a political poet angered by the destruction of ‘an ancient birthright based on co-operation and common rights’:

These paths are stopt – the rude philistine’s thrall

Is laid upon them and destroyed them all

Each little tyrant with his little sign

Shows where man claims earth glows no more divine

But paths to freedom and to childhood dear

A board sticks up to notice ‘no road here’

And on the tree with ivy overhung

The hated sign by vulgar taste is hung

As tho’ the very birds should learn to know

When they go there they must no further go

Thus, with the poor, scared freedom bade goodbye

And much they feel it in the smothered sigh

And birds and trees and flowers without a name

All sighed when lawless law’s enclosure came

And dreams of plunder in such rebel schemes

Have found too truly that they were but dreams.

– John Clare, from The Moors, 1824

As I went walking I saw a sign there

And on the sign it said ‘No Trespassing’

But on the other side it didn’t say nothing,

That side was made for you and me.

– Woody Guthrie, ‘This Land Is Your Land’

When Britain was still a rural economy of land workers, the struggle over access to the land was about economics, about survival. But by the middle of the nineteenth century, half the nation’s population lived in cities and towns. It was in this period that the conflict over common land and rights of way changed from being about economic survival and became – as Rebecca Solnit puts it in Wanderlust – about ‘psychic survival, about a reprieve from the city’. As more and more people chose to spend their spare time walking, more and more of the traditional rights of way were closed to them. The issue became the right to roam.

You can date the desire to roam freely in the countryside back to the Romantic poets. Rebecca Solnit tells the story of a confrontation at Lowther Castle in Cumbria, where Wordsworth was being entertained by the Earl of Lonsdale. At dinner, the earl complained that his wall had been broken down and that he would have horsewhipped the man who did it. At the end of the table, Wordsworth heard the words, the fire flashed into his face and rising to his feet, he answered: ‘I broke your wall down, Sir John, it was obstructing an ancient right of way, and I will do it again.’

Solnit is a great admirer of the English tradition of establishing, and fighting to hold onto, rights of way:

Certainly one of the pleasures of walking in England is this sense of cohabitation right-of-way paths create – of crossing stiles into sheep fields and skirting the edges of crops on land that is both utilitarian and aesthetic. American land, without such rights-of-way, is rigidly divided into production and pleasure zones, which may be one of the reasons why there is little appreciation for or awareness of the immense agricultural expanses of the country. British rights of way are not impressive compared to those of other European countries – Denmark, Holland, Sweden, Spain – where citizens retain much wider rights of access to open space. But rights-of-way do preserve an alternate vision of the land in which ownership doesn’t necessarily convey absolute rights and paths are as significant a principle as boundaries.

Nearly 90 percent of Britain is privately owned, but Solnit expresses her admiration for ‘a culture in which tresspassing is a mass movement and the extent of property rights is open to question’. The movement that fought – and continues to fight – for unfettered access to land and shore began in the late 19th century. The Liberal MP James Bryce, who introduced an unsuccessful bill to allow access to privately held moors and mountains in 1884, declared a few years later:

Land is not property for our unlimited and unqualified use. Land is necessary so that we may live upon it and from it, and that people may enjoy it in a variety of ways. and I deny therefore, that there exists or is recognized by our law or in natural justice, such a thing as an unlimited power of exclusion.

Today, campaigns for footpaths and the right to roam may have support from people of all social backgrounds, but at the dawn of the 20th century, the issue was seen in class terms and became a significant strand in the socialist movement. In 1900 the Sheffield Clarion Ramblers -a socialist organisation – was formed, followed in 1907 by the Manchester Rambling Club. In 1928 the nationwide British Workers Sports Federation and in 1930 the Youth Hostels Association began to provide lodging for young hikers and working class walkers with limited means. Historian Raphael Samuels observed that, ‘hiking was a major, if unofficial, component of the socialist lifestyle’. By the 1920s and 1930s, tens of thousands of workers spent their Sundays walking; in 1932, some 15,000 headed for the hills from Manchester alone each weekend. But they found their access blocked by rich landowners.

Kinder Scout, the highest and wildest point in the Peak District, became the focus of the most famous battle for access. It had been public land until 1836, when an enclosure act divided the land up among the adjacent landowners, giving the lion’s share to the Duke of Devonshire, owner of Chatsworth House. The fifteen square miles of Kinder Scout became completely inaccessible to the public. Walkers called it ‘the forbidden mountain’.

In April 1932, over 400 people participated in a mass trespass onto Kinder Scout. The event was organised by the Manchester branch of the British Workers Sports Federation. Walkers encountered gamekeepers with clubs and police with truncheons (above) during the mass trespass, and five men from Manchester, including the leader, Benny Rothman, were subsequently jailed. One of Ewan MacColl’s greatest songs, ‘Manchester Rambler’, was written in celebration of the Kinder trespass:

I’m a rambler, I’m a rambler from Manchester way

I get all me pleasure the hard moorland way

I may be a wage slave on Monday

But I am a free man on Sunday

I’ve been over Snowdon, I’ve slept upon Crowden

I’ve camped by the Waine Stones as well

I’ve sunbathed on Kinder, been burned to a cinder

And many more things I can tell

My rucksack has oft been me pillow

The heather has oft been me bed

And sooner than part from the mountains

I think I would rather be dead

The day was just ending and I was descending

Down Grindsbrook just by Upper Tor

When a voice cried ‘Eh you’ in the way keepers do

He’d the worst face that ever I saw

The things that he said were unpleasant

In the teeth of his fury I said

‘Sooner than part from the mountains

I think I would rather be dead’.

He called me a louse and said ‘Think of the grouse’

Well I thought, but I still couldn’t see

Why all Kinder Scout and the moors roundabout

Couldn’t take both the poor grouse and me

He said ‘All this land is my master’s’

At that I stood shaking my head

No man has the right to own mountains

Any more than the deep ocean bed

So I walk where I will over mountain and hill

And I lie where the bracken is deep

I belong to the mountains, the clear-running fountains

Where the grey rocks rise rugged and steep

I’ve seen the white hare in the gulley

And the curlew fly high over head

And sooner than part from the mountains

I think I would rather be dead

On its 75th anniversary, the trespass was described by Roy Hattersley as, ‘the most successful direct action in British history’ because, just over a decade later, it achieved a result. The Ramblers’ Association had started its own right-to-roam campaign in 1935 and in 1945, within days of taking office, the Attlee Labour government set up a series of official committees which recommended establishing a system of national parks and establishing the right to roam across all open and uncultivated land. Ten national parks were created but the only access improvement achieved was to strengthen the existing system of public footpaths.

In Finland, Norway and Sweden, the right to walk where you wish is enshrined in the principle of allemansrätt, or ‘every man’s right’. In Sweden, allemansrätt, guaranteed in the national constitution, is considered a central tenet of the national approach to tolerance, its origins stretching back in part to medieval provincial laws and customs. In Scotland the Land Reform Act 2003 grants an extensive right to roam almost anywhere, as long as it is exercised responsibly. But England has always lagged behind.

On the fiftieth anniversary of its creation, the Ramblers’ Association began holding ‘Forbidden Britain’ mass trespasses of its own and in the 1997 election the Labour party promised to support ‘right to roam’ legislation that would at last open the countryside to the citizens. More radical new groups such as This Land Is Ours (founded by George Monbiot) began to take direct action to highlight a situation in which just 6,000 landowners, mostly aristocrats, own about 40 million acres – or two thirds of the land in the UK – over which public access was largely prohibited. But, increasingly it’s not just about aristocrats: since the 1980s the trend has been towards land being bought up by multinational corporations and financial institutions.

Marion Shoard, author of A Right to Roam (1999) has written that ‘underlying successive skirmishes between owners and landless has been a simmering war of competing ideologies in which the supposed right of ownership of the environment has come up against a growing sense that the earth belongs in some sense to all’.

In A Right to Roam, Shoard wrote:

Seventy-seven per cent of the UK’s land is countryside, and this still includes much magnificent scenery. Yet the increasing numbers of people setting off in search of it find their simple quest ends all too often in disappointment and frustration. They can visit the ever more crowded country parks, picnic areas, and other enclaves provided by public and voluntary bodies, but if they try to venture beyond such places and roam freely they soon run up against a harsh reality. Most of Britain’s countryside is forbidden to Britain’s people. They may look at it through their car windscreens but they may not enter it without somebody else’s permission – permission which will be withheld more often than not. The rural heritage they may have loved unthinkingly since childhood turns out to be locked away from them behind fences, walls, and barbed wire. Where they have been expecting relaxation and peace they find instead warnings to keep out and threats of prosecution.

Our law of trespass holds us in its grim thrall throughout our country. Most of us are vaguely aware that those omnipresent ‘Trespassers will be Prosecuted’ signs are partly bluff. But all of us also know that trespass is indeed illegal, whether or not our wanderings are likely to put us in the dock. When an owner or his representative confronts us, we do not usually choose to argue the toss with him about our right to walk in our countryside. If we did, we should lose the argument. He has the right to use force to remove us. As a result, more than 90 per cent of woodland in Oxfordshire, for example, is effectively out of bounds to the walker. […]

Of course no one challenges today the idea of private property. But other societies hesitate to regard the land itself as something that can be owned as absolutely as a piece of jewellery. Our own laws of compulsory purchase and development control implicitly challenge this idea. Deep down we all know it is wrong. Throughout human history, the notion of which of the planet’s resources might reasonably be held as property by individuals has changed as different peoples at different times have developed different ideas of what is right.

In 2000 the Labour government of Tony Blair introduced legislation that established a limited right to roam over mountain, moorland, heath and downland. The bill was passed in the teeth of opposition from landowners (and from the Prime Minister himself, who backed landowners’ calls for voluntary arrangements instead of a public right). Members of the House of Lords called the bill ‘an attack on property and the rights of ownership’ and ‘a travesty of justice’, and warned that it would lead to drug parties, devil worship and supermarket trolleys in Britain’s wild places. Implementation of the Act was completed in 2005, but it didn’t grant a Scottish or Scandinavian-style right to walk anywhere you like, limiting access on foot to 936,000 hectares of mapped, open, uncultivated countryside.

All of this raises the question: Who owns Britain? Some answers are provided in figures from a surprising source. In 2o10, Country Life Magazine published ‘Who Owns Britain?’, thought to be the most extensive survey of its type undertaken since 1872. The findings were revealed via another unlikely source: the Daily Mail:

The top private landowner, not just in Britain but Europe, is the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensbury, whose four sumptuous estates cover 240,000 acres in England and Scotland. But while his land is the most vast, it is not the most valuable, as the net worth depends on how much is farmland, as well as the value of the property and sporting and heritage activities on it.

The most valuable land belongs to Number 4 on the list, the Duke of Westminster, whose Grosvenor Estate, worth a whopping £6 billion, takes in the wealthiest areas of London, including Belgravia and Mayfair [and, I might add, a sizeable chunk of central Liverpool – more about that in a ‘mo].

Simon Fairlie writing in Land magazine highlights the undemocratic and increasingly unequal pattern of land ownership:

Over the course of a few hundred years, much of Britain’s land has been privatized — that is to say taken out of some form of collective ownership and management and handed over to individuals. Currently, in our ‘property-owning democracy’, nearly half the country is owned by 40,000 land millionaires, or 0.06 per cent of the population, while most of the rest of us spend half our working lives paying off the debt on a patch of land barely large enough to accommodate a dwelling and a washing line.

Yet the individual millionaires are now dwarfed by the incredible reach of corporate land-ownership, which barely existed 100 years ago. As the biggest 19th-century landowners such as the Church have been sidelined by economic and social changes, their land has been snapped up by the private sector. Pension Funds own 550,000 acres. Catching up swiftly are foreign investors and even supermarkets. Waitrose owns a 4,000-acre estate in Hampshire, which it runs as a farm, while Tesco’s 2,545 stores alone take up 770 acres.

During the 18th and 19th century, before the advent of local government, the enclosures parcelled up so much of the countryside for country landowners that, according to today’s estimates, only 4% of land in England and Wales is registered as ‘commons’.

And it’s not just the countryside: in the last few decades the enclosures have moved into our towns and cities. Large sections of cities such as London, have long been owned by a small group of wealthy landlords. For example, the Duke of Westminster owned the whole of northern Mayfair, Belgravia and Pimlico, the Duke of Bedford owned Covent Garden while the Earl of Southampton owned the Bloomsbury Estate.

But, generally speaking, for much of the 20th century the ownership and management of property in cities has been in the hands of a diverse patchwork of private landlords, institutions, local government and private individuals. In the last few decades, however, city centre regeneration, especially in declining industrial areas has often taken the form of very large new developments owned and managed by a single private landlord. In Liverpool, the city council handed a single private landlord, Grosvenor Estates, 42.5 acres of land extending over 34 streets for redevelopment on a 250-year lease. This is Liverpool One – a highly successful retail development that has contributed to the resurgence of the city – but one of a type that raises concerns about the erosion of public space in our cities.

It began with Canary Wharf and Liverpool One; now many commentators are drawing attention to a creeping privatisation of public space. Streets and open spaces are being defined as private land after redevelopment. There are now privatised public spaces in towns and cities across Britain.

In the past decade, large parts of Britain’s cities have been redeveloped as privately-owned estates, extending corporate control over some of the country’s busiest squares and thoroughfares. These developments are no longer enclosed shopping malls; they retain much of the old street pattern, spaces open to the sky, and appear to be entirely public to casual passers-by. But the land is private, and members of the public enter the area subject to rules and restrictions set by the developers – and enforced by their own security personnel.

The writer who has done most to map this process is Anna Minton, author of Ground Control. In her book, Minton explains that the current wave of land privatisation started in the 1980s, with the development of Canary Wharf. New Labour gave the process a boost in 2004 when it changed the legal basis by which Compulsory Purchase Orders were assessed. Previously they had to show they were in the public interest; now they need only to demonstrate ‘economic interest’.

The opportunity to reconstruct urban space so radically, Anna Minton argues, was created by the de-industrialisation of the city, and the closure of the factories, works, warehouses and docks which used to dominate the urban landscape. What we’re seeing as a result is a rapid reversal of the long trend through the 19th century by which roads and highways were ‘adopted’ by the local authority. Minton calls this ‘the creeping privatisation of the British public realm’.

From Liverpool One to Cabot Circus in Bristol, privately owned and privately controlled places, policed by security guards and featuring round the clock surveillance, came to define our cities. In London, Westfield Stratford City and the Olympic Park represent the latest stage of this process, based on property finance and retail, and underpinned by large amounts of debt.

The subtitle of Anna Minton’s book is ‘Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-First Century City’. She explains how urban space is increasingly owned by private corporations and watched over by CCTV as developers fear disruption, crime, filth, and chaos. The result, she argues, are standardized urban spaces that look and feel alike wherever they arise: spaces that are impersonal, anonymous, hostile and not inclusive. There are rules and security guards to police them: no music, no busking, no picnics, no alcohol, no photography, no street theatre, no ball games, no skateboarding, no roller-blading, no cycling. And, above all, no protests. Surveillance is widespread, usually via CCTV. ‘The streets’, says Minton, ‘have been privatised without anyone noticing’.

In Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit, drew a bead on the political aspect of this enclosure of once open and public urban spaces. Writing about her native San Francisco, and its tradition of parades and protests, she wrote:

This is the highest ideal of democracy – that everyone can participate in making their own life and the life of the community – and the street is democracy’s greatest arena, the place where ordinary people can speak, unsegregated by walls, unmediated by those with more power. It’s not a coincidence that media and mediate have the same root; direct political action in real public space may be the only way to engage in unmediated communication with strangers, as well as a way to reach media audiences by literally making news. ….. Parades, demonstrations, protests, uprisings and urban revolutions are all about members of the public moving through public space for expressive and political rather than merely practical reasons.

Paul Kingsnorth writing in his book Real England, put it another way:

It is the essence of public freedom: a place to rally, to protest, to sit and contemplate, to smoke or talk or watch the stars. No matter what happens in the shops and cafes, the offices and houses, the existence of public space means there is always somewhere to go to express yourself or simply to escape. … From parks to pedestrian streets, squares to market places, public spaces are being bought up and closed down.

The economist Diane Coyle, writing during the Occupy encampment outside St Paul’s, observed how public life is being designed out of our cities:

One of the striking aspects of the Occupy movement is its claiming of some open spaces in major cities, striking because it puts a line in the ground (literally) against the steady erosion of urban public space during the past quarter century. […]