‘Where England ends half way across a field’ in the Vale of Ewylas, we followed a trail that led eventually to ‘the cleft Church at Cwmyoy, its displaced gravity’ (in Geoffrey Hill’s words from Comus). Unique since no part of it is square or at right angles with any other part, the church tower tilts at an alarming angle that outleans the Tower of Pisa. It’s an astonishing building that stands beneath a crag on the slope of a hillside with scarcely a house in sight. Continue reading “In the Black Mountains: walking a crooked mile to a crooked church”

Tag: walks

Lleyn walks: Lost and no way out at Hell’s Mouth

Half-way through our week on the Lleyn, and the wind which had got up on the second day was still blowing strongly as we drove into the car park at Porth Neigwl (aka Hell’s Mouth) to begin a walk around the headland of Mynydd Cilan. Continue reading “Lleyn walks: Lost and no way out at Hell’s Mouth”

Lleyn walks: Windswept on Black Rock sands

Towards the end of our week on the Lleyn the glass began to rise – the beginning of more than a week during which high pressure brought clear skies across Europe, from Donegal to the Volga.

We had arranged to meet our old friend Annie – for many years now, an exile from Liverpool stranded in a dramatically situated Harlech gaff with stunning views across Cardigan Bay. We met roughly half-way, at the Lleyn’s eastern-most point, at Borth-y-Gest, a village suburb of Porthmadog overlooking the estuary of the Afon Glaslyn where it enters Tremadog Bay. Continue reading “Lleyn walks: Windswept on Black Rock sands”

Lleyn walks: wind and rain on Mynydd Anelog

I have crawled out at last

far as I dare on to a bough

of country that is suspended

between sky and sea.

– RS Thomas

Under a darkling sky, rain was threatening on the first morning of our week on the Lleyn. Not a promising outlook, but undeterred, we pushed open the gate that led directly from the cottage nestled at the foot of Anelog Mountain onto the Wales Coast Path. Continue reading “Lleyn walks: wind and rain on Mynydd Anelog”

Walking Offa’s Dyke path: a group lacking a credible leader

It will seem like a false omen to those who have sworn allegiance to him, but he will remind them of their guilt and take them captive.

– Ezekial, 21:23

This is a walking story that may have a political message – or it just be a load of twaddle in which four guys well past the age of consent lose their way in the wild before common sense puts them on the right path. Continue reading “Walking Offa’s Dyke path: a group lacking a credible leader”

Walking the canal: the road to Wigan Pier

It had been six years since I last walked this stretch of the Leeds-Liverpool canal, at the start of a plan to walk the length of the canal in stages – a project completed in July the following year. Now I was reprising one of the most attractive stretches of the canal – between the small town of Burscough Bridge and Wigan – this time in the company of two friends, Bernie and Tommy. Continue reading “Walking the canal: the road to Wigan Pier”

A walk in Berlin’s Green Forest

If you follow Berlin’s fashionable Kurfurstendamm to its western end you will arrive at the elegant suburb of Grunewald that lies on the edge of the Grunewald, twelve square miles of woodland and lakes where, in 1542, the Brandenburg Elector Joachim II built a hunting lodge at the heart of the royal reserve he named Zum gruenen Wald – the Green Forest.

One day, during our visit to Berlin this month, we set off from the small museum dedicated to the Expressionists of Die Brucke to walk for an hour so through the forest to the Grunewald S-bahn station where we wanted to visit the Gleis 17 memorial to Berlin’s Jews deported to their deaths inn the east from the station’s platform 17. Continue reading “A walk in Berlin’s Green Forest”

Walking the Sandstone trail: three characters in conversation

In her book, Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Rebecca Solnit characterizes walking as, ‘a state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned, as though they were three characters finally in conversation together, three notes suddenly making a chord’. Solnit’s ‘three characters in conversation together’ describes pretty well the walk which saw (more or less) the completion of a project my good friend Bernie and I embarked upon many moons ago – to walk the length of the Sandstone Trail through Cheshire. We were accompanied on this leg of the journey by Tommy, a freshly-retired former work colleague. Our aim was to pick up where Bernie and I left off nearly a year ago and walk the final 16 mile hike that begins with most dramatic section of the Trail before it ends with a sigh, winding its way across the fields and meadows of the Cheshire – Shropshire border, then joining the Lllangollen canal for the last lap into Whitchurch.

Tommy and Bernie stride out

After leaving a car at either end of the hike (rural bus services being virtually extinct in this neck of the woods), we set off from the Pheasant Inn at Higher Buwardsley up Hill Lane, an ancient packhorse route and salters’ way – a short cut over the sandstone ridge linking the Cheshire salt-mining towns of Northwich, Middlewich and Nantwich with the old crossing-points over the Dee to Wales at Farndon and Chester. Salt was a very important commodity at the time, used not only as flavouring but, more crucially in pre-refrigeration times, for the preservation of perishable goods such as meat.

Hill Lane is only one of many such ancient paths and lanes which the Sandstone Trail now follows, a reminder of the importance of these trails in times past, worn by walking feet and the hooves of cattle and horses. As the Scottish poet Thomas A. Clark observes in In Praise of Walking, ‘always, everywhere, people have walked, veining the earth with

paths’:

Walking is the human way of getting about.

Always, everywhere, people have walked, veining the earth with

paths, visible and invisible, symmetrical and meandering.

There are walks in which we tread in the footsteps of others,

walks on which we strike out entirely for ourselves.

A journey implies a destination, so many miles to be consumed,

while a walk is its own measure, complete at every point along

the way.

We press on, treading ‘in the footsteps of others’, and soon reach the spine of the sandstone ridge that rises out of the Cheshire plain. Here, at the southern edge of Peckforton Hill, we pass the Lodge, a picturesque sandstone gatehouse belonging to the Peckforton Estate.

Peckforton Lodge

Peckforton Lodge is a reminder of the days when a monied man could buy up an extensive tract of land, with two villages thrown in: both Peckforton and nearby Beeston were part of an estate purchased by John Tollemache, 1st Baron Tollemache, in 1840. Between 1844 and 1850, Lord Tollemache had Peckforton Castle, a Victorian replica of a medieval castle, built from sandstone dug from a ridge-top quarry, now lost among the trees on the Peckforton Hills.

Local quarries exist all along the Trail, where sandstone was cut to provide building stone for houses, farm buildings and walls throughout this part of Cheshire. I feel at home on sandstone. It is the rock that reared up from the Cheshire plain at Alderley Edge, a few miles from where I grew up, and also the familiar bedrock of the place where I have lived these last fifty years: a city rose-red as Petra, Liverpool was founded on a sandstone bluff at the northern end of the ridge of sandstone which ruptures the Cheshire plain, and along which we now walk.

Bulkeley Hill (photo: Wikipedia)

Following the ridge the Trail leads to Bulkeley Hill, where the National Trust maintains a stretch of ancient woodland.

Bulkeley Hill

The name Bulkeley is first recorded as Bulceleia in 1086 and is from Old English bulluc and leah, meaning ‘pasture where bullocks graze’, suggesting that this was common land to which local villagers would bring their animals to graze. Thinking back, I remember that the primary school I attended, about ten miles or so from here, was on Bulkeley Road

Name Rock viewpoint

There’s a popular viewpoint, up here on Bulkeley Hill, from which on a clear day it’s possible to look west and see the Welsh hills. But not today. Warm and dry it may be – weather we’ve enjoyed since the beginning of September – but, as luck would have it, today, after two days of azure skies, it’s cloudy and dull, the distant hills shrouded in haze.

Through sandstone to Rawhead

So, no sight of the Welsh hills today as we make our way along the steep western escarpment towards Rawhead, the highest point on the Trail where we might have expected panoramic views. Still, we found plenty talk about, we three ‘characters in conversation’. The Scottish referendum was good for a mile or so, and provoked some pretty intense debate. (For myself, I’ve felt for some time that a Yes vote could be liberating for other places – like Liverpool – remote from Westminster and chafing under merciless policies they have not chosen.)

The murky view from Rawhead

Walking also led us to ponder the distances walked by individuals before the motor car arrived. I have been re-reading David Copperfield in which Copperfield (like Dickens himself) walks considerable distances as a matter of course. There is, for instance, a period in which, by day, he works as a legal clerk in central London, then walks out to Highgate to assist Doctor Strong with his dictionary project before walking to Putney to spend time with his fiancée, Dora, then back to his home near St Paul’s. On another occasion he walks the 16 miles from Dover to Canterbury, arriving at his destination in time for breakfast.

Then there’s the early chapter in Wuthering Heights where Mr Earnshaw walks from Haworth to Liverpool and back – 60 miles each way – staggering into the kitchen at Wuthering Heights at 11 pm on the third day. But, as Rebecca Solnit described in Wanderlust, William Wordsworth beat that with an amazing walk in 1790 when, with fellow-student Robert Jones, he walked across France, over the Alps and into Italy before arriving at Lake Como in Switzerland. They had covered a steady 30 miles a day.

That morning I’d read a review of Naomi Klein’s new book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs The Climate, in which she argues that the climate crisis is fundamentally not about carbon levels in the atmosphere, but about the extreme anti-regulatory version of capitalism that has seized global economies since the 1980s and has set us on a course of destruction and deepening inequality – that ‘our economic system’ is at war with life on Earth. Epic walker Wordsworth also had things to say about materialism and losing touch with nature or ‘getting and spending’ as he expressed it in his poem, ‘The World Is Too Much With Us’:

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;—

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not. Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

Rawhead triangulation point: the highest point on the Trail

Beyond Rawhead the path follows a precipitous course along the edge of sheer sandstone cliffs, before dropping down off the ridge to cross the busy A534 Wrexham-Nantwich road (also known as Salters Lane, so we know what the traffic would mainly have consisted of two to three hundred years ago).

Sandstone cliffs at Rawhead (photo: Wikipedia)

At Bickerton women were decorating the church porch and gateway with astonishingly intricate plaits of white flowers: a wedding, or maybe harvest festival, in preparation, perhaps? It looked like a scene from another time; I wish I’d taken a photo.

Holy Trinity Church, Bickerton (photo: Les Needham)

Past the church we headed up the lane and back onto the ridge. This is Bickerton Hill, owned and managed by the National Trust, a geological SSSI for its exposed Triassic sandstones, and a rich mixture of open woodland and lowland heath. Beneath the scattered birches, purple heather was in bloom, there were bright splashes of yellow gorse, and we tasted jet-black bilberries.

Bickerton Hill is one of few remaining areas of heathland in Cheshire, but it hasn’t always been so: the abandonment of grazing in the 1930s allowed birch, pine and oak to grow, shading out the bilberry and heather that had flourished for centuries. But, for a decade now the National Trust has been working to remove the encroaching trees and restore areas of the hill to heathland. Grazing has been reintroduced to halt the spread of the birch trees which have threatened the rare heathland habitat on the hill.

Bickerton Hill: birch, purple heather and bilberries

There were toadstools, too – the iconic ones, bright red with white markings, and familiar from childhood story books. Fly Agaric they’re called, apparently a reference to their use as an insecticide, crushed in milk to attract and kill flies. They also have hallucinogenic properties, and there is a long history of their use in religious and shamanistic rituals across northern Europe.

Fly Agaric: hallucinogenic if consumed

This was where we paused for lunch, with me handing round tomatoes fresh from from the greenhouse on our allotment. (What a summer it’s been for growing: we’re currently overwhelmed with tomatoes, and courgettes that seem to grow as soon as you turn your back. This week we have gathered the first figs from a tree we planted three years ago.)

Taking in the view

We sit on a log and take in the stunning views across the plain towards the Welsh hills. The haze is lifting a little and some sun breaks through, brightening the scene.

My eyes already touch the sunny hill.

going far ahead of the road I have begun.

So we are grasped by what we cannot grasp;

it has inner light, even from a distance-

and charges us, even if we do not reach it,

into something else, which, hardly sensing it,

we already are; a gesture waves us on

answering our own wave…

but what we feel is the wind in our faces.

– ‘A Walk’ by Rainer Maria Rilke

The view from Bickerton Hill

It’s difficult to believe, looking out at the tranquil rural view, that this was once a mining district. But, as at Alderley Edge, further to the north and a few miles from the village where I grew up, the vein of copper that runs along the sandstone ridge was mined beneath the Bickerton Hills from the 17th century onwards. Nearby is an engine house chimney, all that remains of mine buildings demolished in the 1930s.

Up here on Bickerton Hill there is older evidence of human intervention in the landscape. The Sandstone Trail crosses the ramparts of Iron Age Maiden Castle, one of a series of six forts on the sandstone ridge – hilltop sites probably first enclosed in the Neolithic, around 6,000 years ago, to mark them out as special places. By the late Bronze and early Iron Age these hilltop enclosures had become increasingly defensive, possibly to protect and regulate important goods such as salt, grain and livestock.

Packing away the remnants of our lunch, we press on – past the memorial called Kitty’s Stone; placed at the highest point of the hill, it was placed here by Leslie Wheeldon, the benefactor who helped the National Trust acquire the hilltop heathland, and displays poems written by him in memory of his wife, Kitty.

Down off the ridge and through Cheshire farmland

The Trail drops down through Hether Wood to emerge at the end of southern end of the sandstone ridge, close to Larkton Hall Farm. Now we are walking through a classic Cheshire landscape of undulating meadows and hedges, the fields grazed by the black and white cows that seem as much part of the landscape here as the grass and the trees.

Undulating meadows – and a lone hawthorn

Manor House Stables with Bickerton Hill beyond

We pass Manor House Stables with its extensive white-railed training course. Tommy, who ‘laid his first bet when he was five’, fills us in on the details. It’s operated by Tom Dascombe, who is gaining a reputation in the racehorse training world, and owned by Michael Owen, the former Liverpool and Manchester United footballer. It’s a multi-million pound investment and looked it: new buildings that appeared to house luxurious reception facilities for humans, as well as, apparently, state-of-the-art facilities for the horses, including an equine pool, ice bath and veterinary centre

Through the fields

Now the Trail took us through fields, some where maize had been freshly-sown, some golden with the stalks of recently-harvested grain. At Bickley Hall Farm, belonging to the Cheshire Wildlife Trust, we encountered a herd of pretty fearsome-looking (but docile) longhorn cows, part of the Trust’s herd of Longhorn and Dexter cattle, and Hebridean and Shropshire sheep. The Longhorns are the Trust’s ‘living lawnmowers’, a natural way of managing wildflower meadows, heathlands and peatbogs for the benefit of wildlife.

Bickley Hall Farm Longhorns (photo: Tom Marshall)

The winding path

‘The traveller that resolutely follows a rough and winding path will sooner reach the end of his journey than he that is always changing his direction, and wastes the hour of daylight in looking for smoother ground and shorter passages.’ That was the view of Samuel Johnson, and he was surely right. It was late in the afternoon and, as the Trail wound its way across one field after another, at each hedge or stile we hoped to see the long-anticipated Llangollen canal which would signify the final leg of our journey.

Willeymoor lock – and the landlady’s bridge

Then, over a stile and long a hedged path, suddenly we were there on the canal side, at Willeymoor Lock, one of those greatly-anticipated stages of a canal journey where a pub invites a pause. Certainly, for several miles now, what I had been imagining was a significant pause at the waterside with a pint of good beer. But the pub was closed – it would open again at 6pm.

Taking advantage of the outside seating, we nevertheless sat and rested our feet. This is the Llangollen canal, a branch of the Shropshire Union, that runs for 46 miles between Hurleston on the SU and the river Dee above Llangollen. As we sat, the pub landlady appeared and explained in a matter of fact manner that she had run the pub for more than thirty years and felt entitled to a break in the afternoons.

We fell into conversation, and she explained that for several years after taking over the pub she had been unable to cross to the far side of the canal via the lock gates, suffering from a degree of vertigo even more serious than mine. So she had her own bridge built, offering easy access to the far bank and the A49. But then she discovered that British Waterways was entitled to make an annual charge for the convenience!

Navigating the lock

By this stage we had realised that we couldn’t walk the last threee miles into Whitchurch since one of our party had acquired fairly painful blisters. While we waited for a taxi, a barge appeared, navigated by a couple, and we watched (the way you do) as the Canadian half of the crew manipulated the key that opened the lock gates while her partner steered the craft into the lock.

Then it was a brief taxi ride back to our waiting car in Whitchurch, and a surprisingly lengthy drive (had we really walked all that way?) back to our staring point, the Pheasant Inn at Buwardsley. Now, sitting on the pub’s terrace looking out across the Cheshire plain as the clouds lifted sun finally broke through, I was able to savour an excellent local beer – a pint of Weetwood’s Best Bitter, brewed not far away in Tarporley.

Later, driving back towards Liverpool, the western sun shone golden on the ridge of hills we had walked that day. And I thought about the pleasure of walking – something captured in the words of a poem by Thomas Traherne, a 17th century mystic and contemporary of Milton. Born about the year 1636, probably at Hereford, Traherne was the son of a poor shoemaker, and – according to his biographer Gladys Wade, was a happy man:

In the middle of the 17th Century, there walked the muddy lanes of Herefordshire and the cobbled streets of London, a man who had found the secret of happiness. He lived through a period of bitterest, most brutal warfare and a period of corrupt and disillusioned peace. He saw the war and the peace at close quarters. He suffered as only the sensitive can. He did not win his felicity easily. Like the merchantman seeking goodly pearls or the seeker for hidden treasure in a field, he paid the full price. But he achieved his pearl, his treasure. He became one of the most radiantly, most infectiously happy mortals this earth has known.

Most of his poetry is mystical and religious, but in ‘Walking’ he wrote a paean to the secular act of walking

To walk abroad is, not with eyes,

But thoughts, the fields to see and prize;

Else may the silent feet,

Like logs of wood,

Move up and down, and see no good

Nor joy nor glory meet.

Ev’n carts and wheels their place do change,

But cannot see, though very strange

The glory that is by;

Dead puppets may

Move in the bright and glorious day,

Yet not behold the sky.

And are not men than they more blind,

Who having eyes yet never find

The bliss in which they move;

Like statues dead

They up and down are carried

Yet never see nor love.

To walk is by a thought to go;

To move in spirit to and fro;

To mind the good we see;

To taste the sweet;

Observing all the things we meet

How choice and rich they be.

To note the beauty of the day,

And golden fields of corn survey;

Admire each pretty flow’r

With its sweet smell;

To praise their Maker, and to tell

The marks of his great pow’r.

To fly abroad like active bees,

Among the hedges and the trees,

To cull the dew that lies

On ev’ry blade,

From ev’ry blossom; till we lade

Our minds, as they their thighs.

Observe those rich and glorious things,

The rivers, meadows, woods, and springs,

The fructifying sun;

To note from far

The rising of each twinkling star

For us his race to run.

A little child these well perceives,

Who, tumbling in green grass and leaves,

May rich as kings be thought,

But there’s a sight

Which perfect manhood may delight,

To which we shall be brought.

While in those pleasant paths we talk,

’Tis that tow’rds which at last we walk;

For we may by degrees

Wisely proceed

Pleasures of love and praise to heed,

From viewing herbs and trees.

See also

Through the dune slacks of Newborough Warren in search of Marsh Helleborine

Newborough Warren is a very special place, a wilderness of sand dunes, grassland, and damp hollows (or ‘slacks’) crucial for threatened species such as skylark, dune pansies and marsh orchids. It is one of the wildest places I have walked in where the only sound in high summer is the song of a multitude of invisible larks. This is a place that feels far from machinations, procedures, assessment and accounting.

The rising hills, the slopes,

of statistics

lie before us.

the steep climb

of everything, going up,

up, as we all

go down.

In the next century

or the one beyond that,

they say,

are valleys, pastures,

we can meet there in peace

if we make it.

To climb these coming crests

one word to you, to

you and your children:

stay together

learn the flowers

go light

– Gary Snyder, ‘For the Children’

We explored this place on a sultry, overcast day in a circuitous ramble that began at the Marram Grass statue car park and followed the path towards the forest before branching off through a gate into the dunes to the left. Then we headed out towards the strait, following marker posts all the way up across the dunes and down into the slacks.

For centuries rabbits have grazed here (hence the term ‘Warren’), helping to maintain a species-rich habitat. In the 1950s myxomatosis drastically reduced their numbers leaving the dunes in a vulnerable condition, no longer able to support plants and animals. However, rabbit numbers are slowly increasing, and they now graze side by side with horses, helping to keep the dunes healthy by controlling unwanted vegetation.

Semi-wild horses graze on the Warren

This is the largest area of dunes in the British Isles, the result of significant environmental change in the 14th century. At that time Newborough area was an area of rich farmland, the prosperous settlement of Newborough populated by people evicted from Llanfaes, in the north of the island, by Edward I to make way for the construction of Beaumaris castle. But, in the 14th century a series of violent storms buried a large portion of this area under sand dunes. The residents feared that the dunes would completely swallow the town, prompting Elizabeth I to enact a law protecting the marram grass, the roots of which help to stabilize the dunes. This stopped the advance of the dunes and also provided raw material for a new industry in the town, the weaving of marram grass leaves to form mats.

Rabbits soon colonized the dunes, giving rise to the name Newborough Warren and providing locals with another valuable resource – at one time, as over 100,000 rabbits a year were being taken from the warren.

Now Newborough Warren is a National Nature Reserve, consisting of a large expanse of sand dunes, saltmarsh and mudflats. It is the dune slacks – areas which are submerged by winter rains, but drying out during the summer months – which are of most interest to those wishing to see the many wild-flowers for which this site is renowned. The slacks provide the ideal habitat for vast colonies of Northern Marsh Orchids and Marsh Helleborines. We were keen to find some of these rare flowers. They didn’t take much finding.

Northern Marsh Orchid

Pyramidal Orchid

White Common Spotted Orchid

Marsh Helleborine

There’s a lot of glamour and mystery associated with wild orchids, including the belief (which I adhered to) that they’re all rare and endangered. However, when I consulted Richard Mabey’s Flora Britannica, I discovered that although this is true of some species, others are, according to Mabey, ‘proving themselves highly adaptable and capable of moving into the most improbable habitats’ (he cites abandoned waste tips, old colliery land, reclaimed airbase runways and bunkers, motorway roundabouts and power station ash-tips).

Apparently, there are Bee Orchids here, too, but our chosen path through the dunes did not bring us to them. Nevertheless, scattered amongst the marram grass is a wide range of plants such as Dune Pansies, Sea Spurge, Rest Harrow and Viper’s Bugloss. Here’s a gallery of the flowers we chanced upon (hover for details; let me know of any mis-attributions):

As we worked our way over dune and through slack, it was interesting to come across areas colonised by a single large community of a particular plant, whether Helleborines, Orchids, Yellow Rattle or Sea Holly

A colony of Yellow Rattle clustered on the slope of a dune

A field of Sea Holly in one of the slacks

As we neared the shore of the Menai Strait and the ground grew damper, reeds and rushes began to predominate. With the mountains of Snowdonia brooding purple across the water in the heat haze, the landscape felt timeless, or out of time – no sign of human habitation or intervention, no sound but the larks’ song and the rustle of reeds shifting in zephyrs that eased in from the water’s edge.

At last we emerged from the dunes onto Llanddwyn, the beach beneath the mountains. There was no one there but us.

See also

Two churches, two religions, one island

During our week on Anglesey we walked a couple of sections of the coastal path that each led us past an interesting and unusual church. One walk began in Aberffraw, a sizeable village on the southwest coast of the island where the Afon Ffraw debouches into an extensive area of dunes fronted by another stunning beach framed by expansive views of the Snowdon mountain range. An old hump-back bridge spans the river Ffraw here; built in 1731, it was part of the main road into Aberffraw until it was bypassed in 1932.

The 18th century bridge at Aberffraw

I must admit that I’d never heard of Aberffraw before coming here. Yet in early medieval times this place was the ‘capital’ of the kingdom of Gwynedd. For over 800 years the Gwynedd dynasty ruled great swathes of Wales from a royal palace here. The dynasty, established by a chieftain from Strathclyde who came here to expel the Irish from North Wales, resisted Saxons, Vilings, and finally the Normans. After the first Norman incursions into Wales, the royal court moved here from Conway, and Aberffraw came into a golden age which ended with the defeat of Llewellyan the Last by Edward I in 1282, a defeat which brought Welsh independence to an end. Nothing now remains of the palace, which was built of wood. In 1317, with timber in short supply as the once densely-wooded landscape was denuded of trees, the remains of the palce were demolished and its timbers used to repair Caernarfon castle.

Following the estuary out of Aberffraw

We followed the coastal path out along the estuary, absorbing the extensive views across the beach and towards the mountains of Snowdonia. As you work your way out to the next headland the perspective changes as the whole length of the Lleyn peninsula, with its mountainous spine, stretches as far as distant Bardsey Island.

Pushing our way through a profusion of wild flowers

Somewhere along this stretch we encountered one of the most beautiful stretches of coastal path I can recall; the path was deeply-worn, flanked by an earthen bank splashed with the densest profusion of wild flowers – ox-eye daisies, red campion, foxgloves, field scabious and hawkbit. Nearby was a community of Northern Marsh Orchids and clumps of Sea Campion.

Northern Marsh Orchid

Sea Campion

A mile further on, and we spied the first of the two churches that form the main subject of this post- the tiny church of Saint Cwyfan, isolated on a small walled island in the pebble-strewn bay of Porth Cwyfan.

St Cwyfans Church comes into view

This simple medieval church dates from the 12th century and originally stood at the end of a peninsula between two bays. However, in a few decades in the 17th century the sea slowly eroded the coast, turning the peninsula into an island.

St Cwyfans Church

A causeway was built to the island to allow parishioners to get to the island (even that has now largely been washed away). The sea continued to eat away at the island until, in the late 19th century, some of the graves surrounding the church began to fall into the sea. By this time the church was abandoned and roofless, having been replaced by a new church further inland. However, in 1893 a local architect, concerned for the fate of the evocative old church, raised money to save it by constructing a seawall around the island and restoring the building.

‘And its walls shall be hard as their hearts’

The sight of the church perched above its encircling, fortress-like wall stirred a vague memory – was it of a poem by RS Thomas who wrote across the water there, on the Lleyn? It wasn’t until we were back home, and I was able to pull down off the shelf Rita’s copy of Thomas’s collected poems, that I found the answer. It’s a 1972 poem by Thomas called ‘The Island’ which made a powerful impression on me when I first read it. But it was puzzling, too. For me, as an atheist, the poem seemed to speak of the futility of belief in a god so unmindful of humanity’s suffering on earth. Yet Thomas was an Anglican priest who served as a vicar in several small rural, poverty-stricken parishes in Wales – the last, before his retirement, being at Aberdaron, on the remote tip of the Leyn. Even knowing that, ‘The Island’ remains a puzzling poem for me. I suppose it’s a vision of when a ‘rough god goes riding’, in Van Morrison’s memorable expression (there’s an extended discussion of its meaning, for anyone interested, here). However you choose to interpret the poem, St Cwyfan’s church, surrounded by its forbidding wall, seems its perfect visualisation:

And God said, I will build a church here

And cause this people to worship me,

And afflict them with poverty and sickness

In return for centuries of hard work

And patience.

And its walls shall be hard as

Their hearts, and its windows let in the light

Grudgingly, as their minds do, and the priest’s words be drowned

By the wind’s caterwauling. All this I will do,

Said God, and watch the bitterness in their eyes

Grow, and their lips suppurate with

Their prayers. And their women shall bring forth

On my altar, and I will choose the best

Of them to be thrown back into the sea.

And that was only on one island.

The coastal path near Cemaes

Another day, another coastal path walk – this time on the northern coast, setting out from the little port of Cemaes. This coastline is quite different to that around Newborough and Aberffraw – more like Cornwall or Pembrokeshire with its rocky coves and steep cliffs. Unfortunately, walking in one direction at least, it’s overshadowed by the ominously looming bulk of Wylfa nuclear power station on Wylfa head.

Human waste: nuclear and otherwise

Built in 1963, Wylfa was the second nuclear power station to be built in Wales, after Trawsfynydd. Now only one of its two reactors is operational. During its operational life there has been considerable public concern about safety at Wylfa, with Greenpeace commissioning an independent appraisal of problems at the plant. Substantial works have been needed to strengthen the reactors against deteriorating welds discovered in a safety review in April 2000. Now there are plans to build a new nuclear plant alongside the old one. The plan has been the subject of local opposition, led by the group People Against Wylfa B – or PAWB (pawb being Welsh for ‘everyone’). Despite this, the coalition government has confirmed Wylfa as one of the eight sites it considers suitable for new nuclear power plants, with the plant being built by Hitachi. A spokesman for PAWB responded: ‘We don’t want a ‘Wylfashima’ on Ynys Mon’.

Wylfa nuclear power station overshadows the church at Llanbadrig

A couple of miles out of Cemaes we stumbled upon our second unusual church in a coastal setting. Perched close to the cliff edge is Llanbadrig, which translates as ‘church of Saint Patrick’. According to local legend, the church was founded in AD 440 by St Patrick who had been shipwrecked on the small island of Middle Mouse which is visible from the churchyard. The story goes that Patrick, travelling by ship after visiting St Columba on the Scottish island of Iona and bound for Ireland, was shipwrecked on the island but managed to make safe landfall at a cave in the cliffs below where the church now stands.

The church at Llanbadrig: beware of holes

We had a picnic lunch and waited for the church to be opened at two o’clock, for the real curiosity of this church lies in its interior. Meanwhile, we strolled around the gravestones, taking careful note of the warning sign: ‘Beware of holes in this part of the churchyard’. You never know where you might end up!

I wanted to look inside the church because, although it possibly dates back to AD440, it has been modified at various points in its history – most recently undergoing a major restoration in 1884, funded by Henry Stanley, 3rd Baron of Alderley. This was interesting not only because the family seat at Nether Alderley below Alderley Edge in Cheshire is just a few miles from where I was brought up, but primarily because Stanley was a convert to Islam when he funded the restoration. In 1869 Lord Stanley (whose sister Katharine was the mother of Bertrand Russell) became the first Muslim member of the House of Lords.When he died in 1908, an obituary noted:

That the late Henry Edward John Stanley, third Baron Stanley of Alderley, was a sincere and devout Muslim, was known to very few men. Readers of the Safwat-ul-Itbar (Travels of Sheikh Muhammad Bairam Fifth of Tunis), however, knew very well that Lord Stanley had long been a sincere believer in the principles of Islam. But his faith was not limited to a profession by word of mouth. The author of the Safwat-ul-Itbar relates incidents which show how deeply Islam had entered into his heart. He found him not only regular in the five daily prayers, but also constant at tahajjud (the midnight prayers); and what is still more wonderful, he found him very humble in his prayers, and far above most born Muhammadans. When he talked of the Holy Prophet, it was with profound love and deep respect that he mentioned or named him. He found him also very well versed on the principles of Muslim theology, and in his conversation with him he found that the deep conviction of his mind was the result of a comprehensive knowledge of the principles of Islam. This was about the year 1880. Who could imagine that such a sincere and devout worshipper of the true God was living in the heart of Christendom?

This explains why Stanley’s plans for the restoration of the church at Llanbadrig included Islamic-influenced designs. The stained glass windows, instead of depicting biblical scenes and characters, are simple geometric designs. Tiles on the wall behind the alter also show geometric or floral designs. There are some suggestions that he created these designs himself.

Islamic-influenced designs in the church at Llanbadrig

Stanley died and was buried during the most holy period in the Muslim calendar, 21- 25 Ramadan (11 and 15 December 1903 respectively). He was buried according to Muslim rites on the family estate, Alderley Park, at Nether Alderley in Cheshire. The chief mourner at his burial was the First Secretary to the Ottoman Embassy in London. Islamic prayers were recited over his grave by the embassy’s Imam. A service in his memory was held at the Liverpool Mosque, conducted by Abdullah Quilliam, a Liverpool solicitor and another Muslim convert. The mosque, founded by Quilliam, was in those days located in Brougham Terrace. The building later became the city Register Office, where Rita and I were married.

Across the burning sands of Malltraeth and Llanddwyn

The morning was warm, but there was a pleasant breeze that blew white, puffy clouds across a blue sky as we set off across the Cob to Malltraeth. There was no hint of the scorching hours to come.

We had decided to walk along the Cob to the village where the wildlife artist Charles Tunnicliffe had once made a home, and then to return the same way before exploring the Cefni salt-marsh and looping back to the car park via Llanddwyn beach and the track through Newborough Forest.

The Cob and the salt-marsh

The Cob is a mile long embankment, over which the Anglesey Coastal path runs. It is part of a flood defence system, completed in 1812 under the direction of Thomas Telford, which enabled the Cefni Marsh to be drained to facilitate the construction of the A5 turnpike road to the port of Holyhead. Today, the Cob encloses the ‘Pool’, a nature reserve managed by the Countryside Council for Wales. Cefni Marsh is designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, and is the location of an RSPB reserve.

Cefni Marsh and the Pool from the Cob

It was the birds that brought Tunnicliffe here. Like me, he was born in Cheshire and spent his childhood on the family farm, not far from the village where I grew up. He studied art in Macclesfield and won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art.

Charles Tunnicliffe, Swallows on the roof of Shorelands (illustration for ‘What to Look for in Autumn’, Ladybird Books)

Soon he had made his name as a prolific and highly talented commercial artist and engraver whose subject was the countryside and wildlife. In 1932 he illustrated Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter, and in the 1950s and 60s he became widely known for his children’s book illustrations (including the immensely popular Ladybird ‘Seasons’ series) and his wildlife illustrations for cards given away with packets of Brooke Bond tea.

Charles Tunnicliffe, Malltraeth village from the Cob (illustration from ‘Shorelands Summer Diary’)

In 1947, Tunnicliffe and his wife Winifred came to live on Anglesey in a house in Malltraeth called ‘Shorelands’ which looked out directly over the Cefni estuary. In Shorelands Summer Diary (1952) he described their arrival:

On the evening of March the 27th, my wife and I crossed over Telford’s great bridge which spans the Menai Straits, and entered the island county of Anglesey. We were no strangers to this fair country, but our journey to-day was different from all previous ones for, at the end of it, in a little grey village at the head of an estuary, there was an empty house which we hoped to call home as soon as we could get our belongings into it. Our other visits had been short holidays, spent chiefly in watching and drawing birds and landscape of which there was great variety. Several sketch-books and been filled with studies of Anglesey and its birds, and we had been specially delighted to find that he island in spring and autumn was a calling place for many migratory birds, while summer and winter had their own particular and different species. Occasionally, to add to the excitement, a rarity would appear. Whatever the season there were always birds and this fact had greatly influenced us in our choice of a new home. […]

The sun shone, the furniture went into the house … and the Sheldrucks on the sands laughed and cackled all day. There followed days of arranging and re-arranging and gradually order emerged from chaos, the proceedings often suspended while we gazed from the windows. Field-glasses and telescope were always kept in readiness for a sudden grab, but it was astonishing how often they became buried under other material not yet put in its proper place. such was the case when we heard the call of wild geese one evening…

The view of the estuary from Shorelands (illustration from ‘Shorelands Summer Diary’)

With the abundance of bird life and the views across to the distant mountains of Snowdonia, Tunnicliffe settled into a life of painting his favourite subjects. From the window of his studio at ‘Shorelands’, overlooking the estuary, he observed and painted. He watched the birds fishing along the shoreline, the oystercatchers pausing in their quick runs to probe for shellfish. When the geese came sweeping in as winter approached he caught their wingbeats for all to see in his sketch notes.

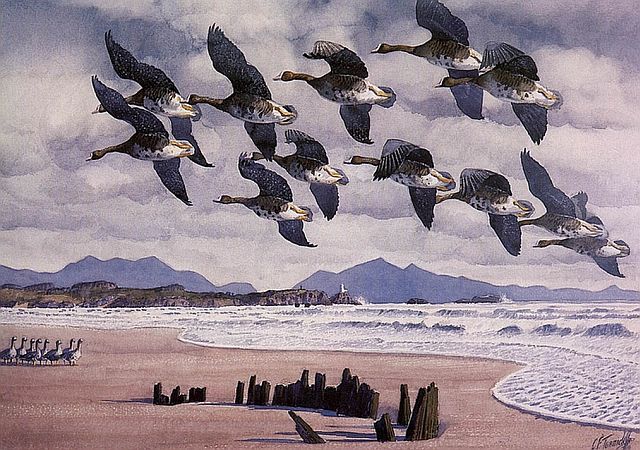

Charles Tunnicliffe, Geese flying up the marsh (illustration from ‘Shorelands Summer Diary’)

In Shorelands Summer Diary Tunnicliffe wrote:

The house is well named ‘Shorelands” for only a stout stone wall and a row of rough upright timbers protect it from the tides of a mile-wide estuary. Years ago the estuary extended almost into the very heart of the island, but in the year 1812 a sea wall was built, and the inland area over which the tides used to flood was reclaimed and is now good farmland, dotted about with grey stone farmsteads, and intersected by numerous dykes and raised earth banks. The sea wall is called locally ‘The Cob’, and it has its beginning very close to the village at a spot where a bridge spans the river and its two flood-water canals. River and canals are disciplined by high man-made banks for some miles inland, indeed as far as the river is tidal. The bridge marks the end of the village street and the beginning of the road over the marsh. After crossing the bridge the road swings slightly inland, then deviates shorewards again and touches the Cob at its far end. Thus, between Cob and road, there is an area of brackish pool and swamp which is beloved of the birds, and both road and Cob make ideal vantage points for their study. Many are the happy hours I, have spent there. […]

But to return home: the windows in the front of the house command views from east to south-west. Looking south-east, with the Cob extending across its whole width, is the mile-wide estuary. Beyond, filling the middle distance, is a long ridge of high ground criss-crossed by hedges and dotted about with farms, which at its seaward end deteriorates into rock and sand-dune, and above this ridge loom the great mountains of Caernarvonshire, the kingdom of Eryri, with Snowdon lording it over all – a stupendous panorama.

Charles Tunnicliffe, High tide over the garden wall (illustration from ‘Shorelands Summer Diary’)

We made our way back along the Cob – slowly, since everyone we met along the way seemed happy to stop and chat awhile. We paused, too, to observe the birds in the marsh, the school of great grey mullet in the Pool, and the horses that roam free across the marsh. Walking in this direction, the views of the distant mountains, seen above the pines of Newborough Forest, are stunning.

Cefni marsh and the distant mountains: as we saw it, and as Tunnicliffe drew it

Back at our staring point, the car park at the Newborough end of the Cob, we now set off to explore Cefni salt-marsh, following the Anglesey coastal path. The first stretch wound through shady woodland – very boggy in wet weather from the evidence of the extensive sections of duckboard provided.

A shady start to this section of the walk

After a mile or so, the path leaves woodland for the open salt marsh, following the edge of Newborough Forest. With tall Corsican pines to our left and acres of marram grass to the right, we followed the path as it continued along the edge of the estuary of Afon Cefni where clumps of tamarisk were in flower.

Out onto the saltmarsh, skirting the edge of Newborough Forest

Tamarisk was not the only flower to be seen along this stretch; as Charles Tunnicliffe observed on June 20th in Shorelands Summer Diary:

The dunes are full of flowers. Viper’s Bugloss stands in spires of blue as vivid as any delphinium; ragged robin blooms in delicate patches of pink, and in the damp places yellow iris is in flower. Hugging the sand the fluffy seed-heads of creeping willow mingle with heartease of an amazing variety of colours from deep blue through yellow to white. Among all this the Wheatears, both young and adult, fly round close to the ground, or perch on some dead stalk and utter their ‘Tcheck! Tcheck!’ flashing their pied tails as they take wing.

Out onto the saltmarsh

Soon we reached the point where the path turns south to follow the sand dunes that edge Penhros Traeth down towards the causeway out to Llanddwyn Island. By now the sun was at its zenith and it was blazingly hot. Although the saltmarsh and sandflats of the Cefni are important feeding areas for wildfowl and wading birds we saw very few. Only mad dogs and Englishmen…

Across the burning sand

When I was a kid, at home we had an old 78 of ‘Cool Water’, recorded by The Sons of the Pioneers in 1948, the year I was born. The words came flooding back as we toiled across the burning sands:

All day I’ve faced a barren waste

Without the taste of water, cool water

Old Dan and I with throats burnt dry

And souls that cry for water

Cool, clear, water

Keep a-movin, Dan, don’tcha listen to him, Dan

He’s a devil, not a man

And he spreads the burning sand with water

Dan, can ya see that big, green tree?

Where the water’s runnin’ free

And it’s waitin’ there for me and you?

It’s water, cool, clear water.

The wreck of the Athena on Traeth Penrhos

The tide was far out and we trudged on across an endless desert of scorching sand. Nearing Llanddywn Island we came upon the remains of a wreck, buried in the sand, but the ship’s spars exposed at low tide. This is all that remains of the Athena, a ship that ran into trouble during a winter storm in December 1852. It was sailing from Alexandria to Liverpool, and hadn’t got far to when it was wrecked upon this shore. Thanks to the courage of the local lifeboat men, the 14 crew of the Athena were rescued and taken to safety on Llanddwyn Island.

At last – cool water!

We were glad, eventually, to find a way through the dunes into the shade of the forest. With some difficulty we found our way back to our starting point through the bewildering maze of trails in the forest. Two thirsty walkers and one very thirsty dog!

See also

Walking out to Llanddwyn island

This time we wanted to walk out to the island. Last September, during a short visit to Anglesey, we chanced upon the beach where the pines of Newborough Forest give way to dunes and some three miles of golden sand. At the far end of Llanddwyn beach is the Island, Ynys Llanddwyn; from a distance it seemed a magical place, its rugged headland topped by two white towers and a tall Celtic cross.

The sandy trail to Llanddwyn Island

Although it is an island, you can walk out it when the tide is low. With dog in tow we set out, only to be frustrated when we encountered notices that informed us the island is out of bounds to dogs. So we had to go over one of us at a time, while the other sat in the shade of the pines with the dog.

Well that just ain’t fair…

I set off across the sand. As you approach the island you pass several large rocks that protrude from the sand. Geologists are excited by these formations: they are pillow lavas, mounds of rock formed by undersea volcanic eruptions. As the hot molten rock met the cold seawater a balloon-like skin was formed, which then filled with more lava, forming the characteristic pillow shape. These rocks extend down much of the length of Llanddwyn Island, giving it its distinctive outline and rolling topography.

Outcrops of pillow lava give form to Llanddwyn Island

Arriving at the island, I was met by the first of what turned out to be a series of elaborately carved gates, decorated with swirling Celtic motifs and elegant lettering. The path beyond was just as lovely, constructed from pebbles and crushed seashells and edged with colourful masses of wild flowers.

Seashells and rocks form the footpath on Llanddwyn

In legend this really is a magical place. The name Llanddwyn means ‘the church of Saint Dwynwen’, the fifth century daughter of a Welsh prince of Brecon. She fell in love with a young man named Maelon, but her father, the King of Powys, forbade their union and had him turned to ice. At this, Dwynwen retreated to the solitude of Llanddwyn Island to follow the life of a hermit, praying that all true lovers find happiness.

She has become the Welsh patron saint of lovers, making her the Welsh equivalent of Saint Valentine. Her feast day, 25 January, is often celebrated with cards and flowers, just as is 14 February is as Valentine’s Day. In Wales, lovers may exchange gifts of love spoons or love jewellery engraved with poetry. Some may even come to Yns Llanddwyn.

The ruins of the 16th century chapel

As the legend of Saint Dwynwen grew, visitors would travel to the island to leave offerings at a small chapel that had become her shrine; indeed, so popular was this as a place of pilgrimage that Llanddwyn became the richest community in the area during Tudor times. A substantial chapel was built in the 16th century on the site of Dwynwen’s original chapel. The ruins of this can still be seen today.

Llanddwyn automatic lighthouse

There are two white towers on the island. The smaller one functioned as a navigational beacon until 1972, when it was turned into an automatic lighthouse. The larger tower at the end of the island, built in 1845, has a distinctive shape, since it was modelled on the windmills of Anglesey. Now closed, in 2004 it featured as a location in the romantic thriller Half Light.

Llanddwyn lighthouse: modelled on the windmills of Anglesey

There are some cottages nearby which date from the early 1800s when they housed pilots who guided vessels into Caernarfon harbour. The pilots also acted as lighthouse keepers and lifeboat men; the cannon in front of the cottages was used to alert members of the lifeboat crew in times of emergency.

A place of outstanding natural beauty

This is a beautiful place. Wildflowers abound. There are multitudes of nesting seabirds (apparently, in the spring Ynys yr Adar, a small islet off the tip of Llanddwyn, hosts one percent of the total British breeding population of cormorants ). Not surprisingly, the wildlife artist Charles Tunnicliffe had a studio on the island for over 30 years. There’s one painting of Tunnicliffe’s, Coming in to Land, which must have been done from sketches made at the mouth of Afon Cefni, looking toward the lighthouse of Ynys Llanddwyn and the Snowdonia mountains beyond. It depicts one of my favourite sights, a skein of geese in flight. You can hear the honking.

Charles Tunnicliffe, ‘Coming in to Land’

Then it was Rita’s turn to see the island, while I sat in the shade of the pines on a stiflingly hot day with a dozing dog. Reunited, the three of us made our way back along the path through the forest, and along the edge of Newborough Warren’s dune slacks, back to the cottage for tea.

Returning for tea through the Corsica pines

On YouTube there is a video of scenes shot on Llanddwyn Island, with music by Llangwm Male Voice Choir: