I wrote these posts on 20 and 21 January 2009. No further comment required, I think. Continue reading “‘Change has come to America’: how I saw the Obama inauguration”

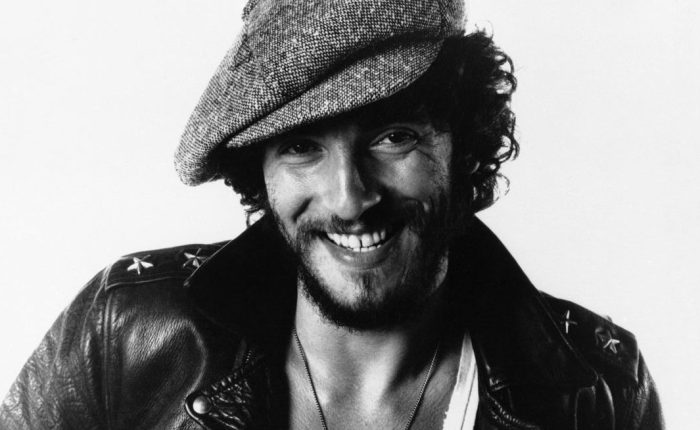

Tag: Bruce Springsteen

Barack on Bruce: ‘sprung from a cage out on Highway 9’

On my last birthday, my lovely daughter gifted me Bruce Springsteen’s autobiography, Born to Run. For any Springsteen fan, it’s an absorbing read and even though I had already consumed Peter Ames Carlin’s biography Bruce, I learned much about the man’s early life and family, and the grind of his early music-making days with his first bands playing along the Jersey shore – many details that only the man himself could know. Though the reviews focussed on the book’s revelations about the periods during which he has suffered from depression, for me the most enthralling sections were those where Springsteen describes a couple of hair-raising and eventful road trips across America.

I was reminded that I’d never got round to writing about Springsteen’s book when I read a report about President Obama bestowing the Presidential Medal of Freedom (America’s highest civilian honour) on Springsteen yesterday in a ceremony at the White House. Springsteen’s book is over 500 pages long. Here’s the concise version, courtesy of Barack Obama. It’s rather good: Continue reading “Barack on Bruce: ‘sprung from a cage out on Highway 9’”

Springsteen in Manchester: holy communion

What felt like urban gridlock apocalypse meant that it took us nearly four hours to drive the 35 miles to Manchester and caused us to miss the first hour of the opening night of the UK leg of Bruce Springsteen’s River tour at the Etihad Stadium.

So while the Boss was powering ahead with the E Street Band on tracks such as ‘Two Hearts’, ‘Hungry Heart’ and ‘Crush on You’ from the classic 1980 album (and inviting a man dressed as Father Christmas onto the stage to join him in an impromptu rendition of ‘Santa Claus Is Coming To Town‘), we were locked down in the worst traffic chaos I have ever experienced – the result, apparently, of four simultaneous accidents that shut down Manchester’s entire tram network. Continue reading “Springsteen in Manchester: holy communion”

The music in my head (part 1): recycled and new this year

There’s a programme on Radio 4 that I hear sometimes when I’m driving in the car. Called Recycled Radio, it chops up old BBC programmes and recycles the snippets into something new. That made me think of all the recycled music I listen to, with album tracks often reassembled into new playlists. As I get older, I listen to a lot of recycled music – but not all the time. Every year brings exciting new sounds. In this post (the first of three) I want to round up some of the music – recycled and new – that I’ve enjoyed in 2015 but never got round to writing about. Continue reading “The music in my head (part 1): recycled and new this year”

Highway 61 Revisited at 50: we never engaged in this kind of thing before

Unlike Bruce Springsteen, I can recall no revelatory experience on first hearing ‘Like a Rolling Stone’. Indeed I cannot recollect the first occasion when I first heard the song – or any other track from Highway 61 Revisited, the album with which it opens. I can, however, relive the exact moment when I first heard ‘Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’ off Dylan’s next album. Such are the vagaries of memory. Continue reading “Highway 61 Revisited at 50: we never engaged in this kind of thing before”

When Springsteen played East Berlin

In one of those curious coincidences that seems to happen to me frequently, the morning after we returned from our short break in Berlin BBC Radio 4 broadcast a drama based on the moment in July 1988 when, improbably, Bruce Springsteen performed before an audience of 300,000 people from all over the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in East Berlin in a concert watched live on state television by millions more. Continue reading “When Springsteen played East Berlin”

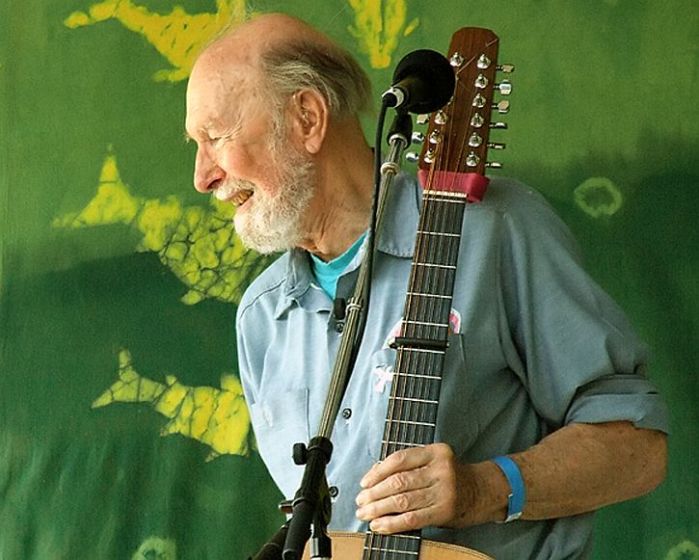

Blessed be the Nation: the story sung by Pete Seeger

Pete Seeger, photo by Anthony Pepitone (Wikipedia)

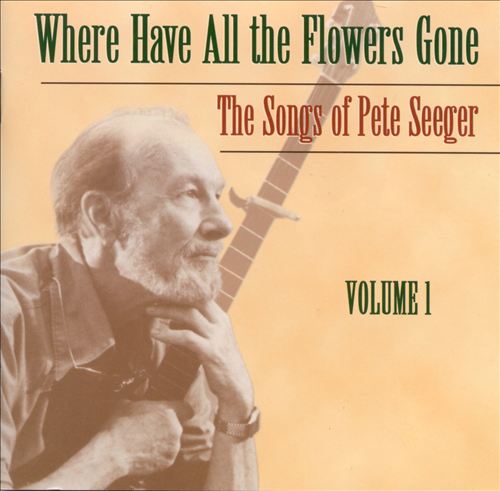

Following the death of Pete Seeger I came across reviews of an album put out in 1998 by Appleseed Recordings, an idealistic independent music label set up by Jim Musselman, a lawyer and activist who once worked with Ralph Nader. Musselman has devoted the label to releasing socially conscious contemporary and traditional folk and roots music by established and lesser-known musicians. On the Appleseed website, Musselman speaks of the years when he worked with Ralph Nader:

I travelled the country for eight years, criss-crossing America in a Guthrie-esque way, seeing the nation and its citizens up close, learning the best ways to listen and to communicate. When I was organizing local communities to fight back against multinational corporations, I would start our open public meetings with a song, figuring that unifying people in singing was an important first step to unifying them in political action.

In 1997, for Appleseed’s first major project, Musselman approached numerous well-known musicians, along with writer Studs Terkel with a request to each record a song written, adapted or performed by Pete Seeger for a tribute album to highlight Seeger’s musical contributions and his tradition of mixing songs and political activism. The resulting double CD Where Have All the Flowers Gone: The Songs of Pete Seeger was the one I stumbled across as I followed internet references to Seeger in the days after his death.

It’s a terrific album from which you gain a holistic sense of the man and the causes he embraced. Jim Musselman also did a great job choosing songs from Seeger’s vast repertoire and matching each tune with an artist ‘based on either the philosophical fit between the artist and the message of the song and/or their unique musical style’, as he writes in the accompanying booklet. As an example of this approach, take the opening track – ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone’ – sung by Irish songwriter and peace activist Tommy Sands with Bosnian Vedran Smailovic (‘the Cellist of Sarejevo). Bear in mind that this was recorded in 1997, before the Good Friday agreement in Northern Ireland and only months after the lifting of the siege of Sarejevo.

The album includes 37 versions of Seeger-related songs specially recorded by luminaries such as Bruce Springsteen, Jackson Browne, Billy Bragg, Sweet Honey In The Rock, Ani DiFranco and many others. The material is wonderful, every song reinforcing the picture of Seeger as both an interpreter of musical tradition and as a crusader for social justice. The performances are first-rate, with many highlights. Bruce Springsteen’s gentle reading of ‘We Shall Overcome’, for example, precedes the version he recorded for his album, The Seeger Sessions many years later, while Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt offer a lilting reggae-inflected account of ‘Kisses Sweeter Than Wine’. There are the songs that reflect Seeger’s later commitment to environmental issues and his campaign (entirely successful) to clean up his beloved, polluted Hudson river, such as ‘Sailing Down My Golden River’.

A remarkable, if less musical interlude comes with Ani DiFranco singing ‘My Name Is Lisa Kalvelage’, Pete’s adaptation of the words spoken in May 1966 by Lisa Kalvelage, one of four women who stopped a shipment of napalm to Vietnam by standing on a loading platform and refusing to move. Seeger’s words come from the statement she made in court after being arrested. Kalvelage likened her protest to lessons she learned from being raised in Nazi Germany – never to keep silent:

If you live in a democratic country where the government is you, you cannot say, ‘I followed orders,’ ” she told a reporter. “If you recognize that something is wrong, you have to speak out to set it straight.

But the words I really wanted to pass on in this post come from one of the two recitations on the album by the late Studs Terkel. It’s a reading of ‘Blessed Be The Nation’, verses Seeger left on a rock on an island where he had camped with his youngest daughter. He elaborates in the CD booklet:

In 1964 I took my youngest daughter canoeing on a beautiful lake in Maine. We camped on a little island and were dismayed to see the beach littered with bottles and cans. We picked ’em all up. I had a marker with me and wrote this graffiti on a flat stone. I never wrote a tune, but someone else can try.

Seeger never put music to these words. I’d like to share them here:

Cursed be the nation of any size or shape,

Whose citizens behave like naked apes,

And drop their litter where they please,

Just like we did when we swung from trees.

But blessed be the nation and blessed be the prize,

When citizens of any shape or size

Can speak their mind for any reason

Without being jailed or accused of treason.

Cursed be the nation without equal education,

Where good schools are something that we ration,

Where the wealthiest get the best that is able,

And the poor are left with crumbs from the table.

Blessed be the nation that keeps its waters clean,

Where an end to pollution is not just a dream,

Where factories don’t blow poisonous smoke,

And we can breath the air without having to choke.

Cursed be the nation where all play to win,

And too much is made of the colour of the skin,

Where we do not see each other as sister and brother,

But as being threats to each other.

Blessed be the nation with health care for all,

Where there’s a helping hand for those who fall,

Where compassion is in fashion every year,

And people, not profits, is what we hold dear.

There’s a recording of Studs Terkel reading the words on YouTube:

In another song on the album – ‘False from True’, sung by Guy Davis – Seeger ruefully observes the limits of protest in song. But, as he remarks in the verse, he continued to sing our story for as long as he had breath within. For that we can be thankful, for the words continue, inspiring succeeding generations:

No song I can sing will make a politician change his mind,

No song I can sing will take the gun from a hate-filled man;

But I promise you, and you, brothers and sisters of every skin,

I’ll sing your story while I’ve breath within.

Pete Seeger: he surrounded hate and forced it to surrender

‘He’s gonna look like your granddad if your granddad can kick your ass.’

Four years ago, Pete Seeger celebrated his 90th birthday party with a sell-out concert at Madison Square Garden. Characteristically, it was a fundraiser for a campaign to which he’d dedicated years of his life: cleaning up New York’s Hudson River. That night, Bruce Springsteen introduced Seeger with these words:

He’s gonna look a lot like your granddad that wears flannel shirts and funny hats. He’s gonna look like your granddad if your granddad can kick your ass. At 90, he remains a stealth dagger through the heart of our country’s illusions about itself.

And that’s the truth. Pete Seeger, who died yesterday aged 94, opposed McCarthyism, and worked tirelessly on behalf of civil rights movement, making his first trip south at the invitation of Dr. Martin Luther King in 1956. One of the seminal political events in his life, and the one which solidified his intent to make actively combating racism a lifelong pursuit, was the 1949 Peekskill race riots. In this video, Seeger recounts his experiences:

Seeger is the only singer in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame who was convicted of contempt of Congress. In 1955, he refused to testify about his past membership in the Communist Party. He had quit the party in 1949 though, he later admitted, should have left much earlier. ‘It was stupid of me not to…I thought Stalin was the brave secretary Stalin and had no idea how cruel a leader he was’. His conviction was overturned on appeal in 1961, but Seeger continued to be blacklisted by American TV networks until 1967. CBS censored parts of his anti-Vietnam War song, ‘Waist Deep in the Big Muddy’, when he sang it on the Smothers Brothers’ Comedy Hour.

Poet Carl Sandberg dubbed Pete Seeger ‘America’s tuning fork’, and there’s little doubt that Seeger helped introduce America to its own musical heritage, devoting his life to using the power of song as a force for social change. He went from the top of the pop charts (‘Goodnight Irene’) to the blacklist and was banned from American commercial television for more than 17 years. In his nineties, Seeger continued to invigorate and inspire the musicians – most notably Bruce Springsteen, whose album We Shall Overcome – The Seeger Sessions was a tribute, comprising songs popularized by Seeger. Three years later, Springsteen persuaded Seeger to sing ‘This Land Is Your Land’ with him at Obama’s inaugural concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

Seeger sang the two ‘radical’ verses of the Woody Guthrie song that invariably get cut when it is sung in public, or in American schools:

As I was walking – I saw a sign there

And that sign said – no trespassing

But on the other side …. it didn’t say nothing!

Now that side was made for you and me!In the squares of the city – In the shadow of the steeple

Near the relief office – I see my people

And some are grumbling and some are wondering

If this land’s still made for you and me.

He sang the song again last September in one of his last public performances at a Farm Aid concert in Saratoga Springs, New York state. As well as Guthrie’s ‘radical’ verses, Seeger inserted another verse of his own that protested fracking in New York state – through the decades he has campaigned on environmental issues, leading a successful crusade in the 1970s to clean up New York’s Hudson River, which was so heavily polluted that there was nowhere on its course that was safe to swim in. He built a boat, the Clearwater, that travelled the Hudson River, drawing attention to the polluted condition of the river. He founded the Clearwater organization which supports environmental education programmes in schools and campaigns for tighter environmental laws.

Pete Seeger came from a wealthy, yet highly politicised radical family. He was born at his grandparent’s estate in Patterson, New Jersey in 1919, the son of musicologist Charles Seeger and his wife, Constance de Clyver Edson Seeger, a violin teacher. Both parents could trace their ancestors to the Mayflower.

His father was a pacifist during World War I whose pacifism, while teaching music at the University of California, cost him his teaching position. In the 1930s Pete was attending Harvard, hoping to become a journalist. In 1936, at a folk song and dance festival he heard a five string banjo for the first time and his life was changed forever. By 1938 he was passing out leaflets for Spanish civil war relief on the Harvard campus and had joined the Young Communist League. He left Harvard in the spring of 1938 without taking his exams.

He went to New York where he found work with the Archives of American Folk Music. Seeger sought out legendary folk song figures including Leadbelly. Inspired by these people and learning much about folk music, he began working with the five string banjo and soon became an accomplished player.

In 1940, Seeger met Woody Guthrie and together they formed the Almanac Singers, a musical collective including Lee Hays, Millard Lampell, Sis Cunningham, Brownie McGhee, Sonny Terry and others. They recorded union songs, such as ‘The Talking Union Blues’ which they wrote as an organizing song, as well as pacifist songs. Drafted into the Army in 1942, the FBI was already building a file on Seeger because of his left-wing activities.

In 1945, after his discharge from the Army, Seeger founded the People’s Songs collective but by 1949 it had gone bankrupt. On 4 Sepember 1949, Paul Robeson was scheduled to perform with Seeger at the Lakeland Picnic Grounds in Peekskill. A large mob of anti-communist vigilantes stormed the venue, attacking performers and members of the audience. While trying to drive away from the scene, Seeger’s car was attacked by vigilantes. His wife Toshi and their three year old son Danny were injured by flying glass.

In the late 1940s, Seeger and Lee Hays wrote ‘If I Had a Hammer’. In 1950 Seeger, Hays, Fred Hellerman and Ronnie Gilbert formed the Weavers. They achieved great success, especially with their recording of the Leadbelly tune ‘Goodnight Irene’.

However, blacklisting in the McCarthy era put paid to commercial success for the Weavers. During the 1950s Seeger occasionally performed with the Weavers but mainly paid the bills with his appearances on the college circuit, and with recordings for Folkways Records (including albums of songs for children, two of which our daughter would play repeatedly when young).

In 1956, after writing ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone?’ Seeger, Arthur Miller and six others were indicted for contempt of Congress by the House of Representatives. He was found guilty of contempt in 1961 and sentenced to ten years in prison. He was released from prison in 1962 when his case was dismissed on a technicality.

During the folk music revival of the early 1960s, the TV networks occasionally invited Seeger to appear on folk music shows like Hootenany, but quickly dropped him when they discovered that he had been blacklisted.

Pete Seeger singing If I Had a Hammer at SNCC rally in Greenwood, MS, 1963

Seeger became involved in the civil rights marches in the South, both as a marcher and as a performer for the marchers. One notable occasion was at Greenwood in Mississippi in the summer of 1963 when there were voter registration drives underway in various communities, one of which was in Greenwood. On 2 July, Seeger performed at a SNCC rally before a small gathering of civil rights workers, singing ‘If I Had a Hammer’. Bob Dylan sang ‘Only A Pawn in Their Game’, written following the murder of Medgar Evers less than a month earlier, on 12 June.

Pete Seeger’s version of ‘We Shall Overcome’ became the anthem of the movement. He discussed the origins of the song in an interview in 2006:

Seeger was strongly opposed to the Vietnam War. In September 1967 he appeared on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour on CBS-TV where he was scheduled to sing ‘Waist Deep in the Big Muddy’, an attack on the war, but the song was cut by the network censors.

‘Songs won’t save the planet’, Seeger told his biographer David Dunlap, author of How Can I Keep From Singing? ‘But, then, neither will books or speeches…Songs are sneaky things. They can slip across borders. Proliferate in prisons.” He liked to quote Plato: “Rulers should be careful about what songs are allowed to be sung.’

I have been singing folk songs of America and other lands to people everywhere. I am proud that I never refused to sing to any group of people because I might disagree with some of the ideas of some of the people listening to me. I have sung for rich and poor, for Americans of every possible political and religious opinion and persuasion, of every race, colour, and creed.

Pete Seeger on The Johnny Cash Show in 1970 complete and uncut

It takes a worried man to sing a worried song….

Pete Seeger with Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee: ‘Down by the Riverside’

In 2012 Pete recorded a hearty version of Bob Dylan’s ‘Forever Young’ for an Amnesty International fund-raising album:

‘This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender’

John Nichols’ closes a fine elegy on The Nation website (which reminds us that Seeger played a banjo inscribed with the message ‘This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender’) with these words:

He showed us how to do our time with grace, with a sense of history and honour, with a progressive vision for the ages, and a determination to embrace the next great cause because the good fight is never finished. It’s just waiting for a singer to remind us that: ‘The world would never amount to a hill of beans if people didn’t use their imaginations to think of the impossible’.

As I mentioned earlier, the fine biography of Pete Seeger written by David Dunaway is entitled How can I keep from singing? – taking its title from an old 19th century hymn revived and adapted by Pete in the early 1950s

My life flows on in endless song

Above earth’s lamentations,

I hear the real, though far-off hymn

That hails a new creation.

Through all the tumult and the strife

I hear it’s music ringing,

It sounds an echo in my soul.

How can I keep from singing?

While though the tempest loudly roars,

I hear the truth, it liveth.

And though the darkness ’round me close,

Songs in the night it giveth.

No storm can shake my inmost calm,

While to that rock I’m clinging.

Since love is lord of heaven and earth

How can I keep from singing?

When tyrants tremble sick with fear

And hear their death knell ringing,

When friends rejoice both far and near

How can I keep from singing?

In prison cell and dungeon vile

Our thoughts to them are winging,

When friends by shame are undefiled

How can I keep from singing?

So long, Pete. It’s been good to know you.

American Masters: Pete Seeger: The Power of Song (PBS)

Seeger at his home in Beacon, New York state in March 2009

The baton passed to another generation

See also

- Happy birthday, Pete Seeger: post here on Pete’s 90th

- In praise of Pete Seeger: posted after Seeger’s appearance at Obama pre-Inauguration concert

- Pete Seeger: the man who brought politics to music (Dorian Lynskey’s Guardian tribute)

- Pete Seeger, Folk Legend, Dead at 94 (Rolling Stone)

- Pete Seeger: interview with Pitchfork magazine, November 2008

- Springsteen Pays Tribute to Seeger (Mother Jones)

- When Pete Seeger Faced Down the House Un-American Activities Committee (Slate)

Don’t you know it’s darkest before the dawn

And it’s this thought keeps me moving on

If we could heed these early warnings

The time is now quite early morning

If we could heed these early warnings

The time is now quite early morning

Some say that humankind won’t long endure

But what makes them so doggone sure?

I know that you who hear my singing

Could make those freedom bells go ringing

I know that you who hear my singing

Could make those freedom bells go ringing

And so keep on while we live

Until we have no, no more to give

And when these fingers can strum no longer

Hand the old banjo to young ones stronger

And when these fingers can strum no longer

Hand the old banjo to young ones stronger

So though it’s darkest before the dawn

These thoughts keep us moving on

Through all this world of joy and sorrow

We still can have singing tomorrows

Through all this world of joy and sorrow

We still can have singing tomorrows

‘Springsteen and I’: the inseparable bond between artist and audience

Bruce Springsteen generally opens a show with this invocation to the crowd: “We’re here tonight because what we need to do we can’t do by ourselves. We need you. We need you”. Then he’ll chant, “Can you feel the spirit? Can you feel the spirit now?” Before he’s sung a note, audience and performer are united in an inseparable bond.

Is this sort of thing unique to Springsteen? Maybe. What is certain is that there is something very special about Springsteen’s relationship with his audience, and his own perception of what the nature of that relationship should be. This is what hits you repeatedly in the new documentary film Springsteen and I that I saw at one of the national preview screenings on Monday night. Continue reading “‘Springsteen and I’: the inseparable bond between artist and audience”

Reading Mr. Springsteen

For Christmas my daughter bought me a copy of Bruce by Peter Ames Carlin, the first biography of Bruce Springsteen in 25 years to have been written with the co-operation of the singer. Books of this genre tend towards the adulation of the dedicated fan, notably, in Springsteen’s case, Dave Marsh’s Born to Run: The Bruce Springsteen Story (1979) – the work of an unabashed partisan and friend whose wife has for some time been a member of Springsteen’s management team.

Which raises the question – why do we read books like these? Is it to bask further in the warm glow cast by the star we adore? Or is it a prurient interest in what dirt the writer might have dug up from the subject’s personal life? Carlin’s book steers a fairly steady course between these extremes: it doesn’t read like hagiography, and it’s not an aauthorisedbiography (though Springsteen did meet with and talked to Carlin on the phone a few times). Carlin writes, ‘Bruce Springsteen made it clear that the only thing I owed him was an honest account of his life. He welcomed me into his world, spoke at great length on more than a few occasions, and worked overtime to make sure I had all the tools I’d need to do my job.’ Yet, despite his access to Springsteen, members of his E Street Band, his family and past lovers, Carlin has not been blinded by standing so near the light.

Bruce and sister Ginny on the Jersey shore, circa 1955

Bruce and sister Ginny on the Jersey shore, circa 1955

So then there’s a further question: will a long-term Springsteen fan like myself learn anything new here? The major events of Springsteen’s life have been so thoroughly explored by journalists in magazines like Uncut, in documentaries and interviews, and by fans on the Web that it might seem there would be little to add. Furthermore, Springsteen’s songs are often read as a memoir written in verse, the lyrics mining his life whilst brilliantly mythologising it.

The answer to the question, surprisingly, is yes. Carlin’s account does offer new insights, and will be read with interest who loves Springsteen’s work, though some of the personal history that inspired his lyrics was already revealed in the personal introductions to each album’s worth of songs which Springsteen wrote for the magnificent edition Songs, published in 2003 and now out of print (another gift from my thoughtful daughter).

Carlin focuses his account on Springsteen’s early life and the early stages of his musical career, with 21 of the 27 chapters devoted to the period up to 1989 during which he painstakingly built and established his legend. As for the rest – well, Carlin reveals aspects of Springsteen that differ from the one we think we may know. It’s a portrait of a man who in recent years has overcome personal doubt and insecurities with anti-depressants and psychotherapy, who is more than a little narcissistic and can sometimes be bad-tempered, and who at times in the past has treated women badly, his band members heartlessly, and driven everyone around him mad with his perfectionism. Well no-one’s perfect.

Carlin explores Bruce’s antecedents at some length in the opening chapter, telling how Joosten Springsteen left Holland for New York in 1652, and sometime in 18th century a branch of the family drifted out to the farmlands of Monmouth County, New Jersey. Right into the 20th century, Springsteens worked as farm labourers and, as industrialization came to New Jersey, as factory workers in Freehold, the town where Bruce was born in 1949. On his mother’s side were Irish immigrants from Kildare who migrated to America in 1850, settling in Monmouth County and working the fields. This was the working life that Bruce has placed at the heart of many of his songs.

Bruce makes clear that material deprivation was indeed a fact of life in a childhood where neither heat, hot water, nor the certainty of a roof over the family’s heads could be taken for granted. Until Bruce was six years old the family – Bruce, sister Virginia and parents Adele and Douglas – lived with Doug’s parents in their rundown home of peeling paintwork and crumbling ceilings. In Songs, Springsteen speaks of how later, after the success of Born to Run, he wanted to write about his own experience:

I was the product of Top 40 radio songs. Songs like the Animals’ ‘It’s My Life’ and ‘We Gotta Get Out of This Place’ were infused with an early pop class consciousness. That, along with my own experience – the stress and tension of my father’s and mother’s life that came with the difficulties of trying to make ends meet – influenced my writing. I had a reaction to my own good fortune. I asked myself new questions. I felt a sense of accountability to the people I’d grown up alongside. […] Most of my writing is emotionally autobiographical. You’ve got to pull up the things that mean something to you in order for them to mean anything to your audience. That’s how they know you’re not kidding.

Indeed, traced through Carlin’s account in Bruce, is a portrait of a young man who, from his late teens, had developed a very clear sense of what he wanted to achieve through a career in music: to weave lyrics rooted in his own experience into the various currents of American popular music – blues and folk, rhythm and blues and doo wop, rockabilly and rock – to create music that spoke to the lives, work and dreams of ordinary Americans.

Speaking of the recording sessions for The Wild, The Innocent and the E Street Shuffle that began in May 1975, Springsteen observed (in Songs) that:

I was drawing a lot from where I came from. I’m going to make this gumbo, and what’s my life? Well, New Jersey. New Jersey is interesting. I thought that my little town was interesting, the people in it were interesting people. And everyone was involved in the E Street shuffle: the dance you do every day just to stay alive. That’s a pretty interesting dance, I think. So how do I write about that? I found it very compelling, and I also wanted to tell my story, not somebody else’s story.

One of the elements of that story concerned his troubled relationship with his father, and Carlin builds a disturbing picture of Bruce’s father, whose crushed life and conflicts with his son was to be the subject of many songs and concert monologues:

Douglas Springsteen spent most of these years huddled inside himself, handsome in the brooding fashion of actor John Garfield, but too lost in his own thoughts to find a connection to the world humming just outside his kitchen window. Often unable to focus on workplace tasks, Doug drifted from the Ford factory to stints as a Pinkerton security guard and taxi driver, to a year or two stamping out obscure doo-dads at the nearby M&Q Plastics factory, to a particularly unhappy few months as a guard at Freehold’s small jail, to occasional spurts of truck driving. The jobs were often bracketed by long periods of unemployment, the days spent mostly alone at the kitchen table, smoking cigarettes and gazing into nothing. […] When dinner was over and the dishes were done, the kitchen became Doug’s solitary kingdom. With the lights out and the table holding only a can of beer, a pack of cigarettes, a lighter, and an ashtray, Doug passed the hours alone in the darkness.

According to Carlin, Bruce’s life was changed the day he picked up a guitar after seeing Elvis Presley on television. Another key moment was hearing ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ on the car radio in 1964. The following Christmas, his mother borrowed $60 to buy Bruce a shimmering black and gold electric guitar. By 1965, Springsteen was playing in bands that performed in bars and beach clubs along Jersey Shore. For seven years he played in bands with names like The Castiles, Child and Steel Mill, before auditioning for John Hammond at Columbia Records in 1972. It was a tough, but essential apprenticeship, performing a repertoire that leaned mostly on Top 40 radio hits with an emphasis on the harder-edged singles by the Stones (‘Satisfaction’ and ‘The Last Time’), the Kinks (‘All Day and All of the Night’), Ray Charles (‘What’d I Say’), the Who (a furious ‘My Generation’), and Hendrix. At the same time, Bruce was honing his guitar technique, for which he was gaining a local reputation, and beginning to write a few of his own songs with ‘thump and snarl’ and ‘fist-in-the-air lyrics’.

But Bruce was already seeking a new direction, searching for new sounds. Enraptured by Van Morrison’s Street Choir album , he decided that Van’s meld of rock, blues, jazz, Celtic, and gospel music should be his new band’s defining sound:

The swing of old-fashioned rhythm and blues; the lockstep funkiness of James Brown; the seemingly endless possibilities that went along with a larger lineup of musicians, sounds, and inspirations. Asbury Park overflowed with musicians capable of playing all of it…

So was born Dr Zoom and the Sonic Boom, an outsize band ‘whose real mission revolved around fun and just the right touch of strangeness’. Soon renamed the Bruce Springsteen Band, the band would appear in either nine-piece or five-piece (Bruce, Steve Van Zandt, Gary Tallent, David Sancious, and Vini Lopez) configurations.

Bruce, Carlin writes, was consciously straining toward the creation of a music that would describe his neighbourhood ‘in a dying city’ struggling through the aftermath of riots and economic depression:

Long segregated along racial lines – the African-American community and other non-whites lived almost exclusively on the town’s tumbledown west side – Asbury Park’s beachside businesses were notorious for keeping African-Americans from all but the lowest-echelon jobs. Tensions had been on a low boil for years, but the combination of a heat wave, cutbacks in social programs, and a jobs shortage touched off days of on-and-off rioting that burned significant pieces of the west side before turning on the city’s business district. The wave of destruction, and the racial and social conflicts that remained unresolved, reduced Asbury Park to a scorched shadow of its once-prosperous self.

Yet Asbury Park still burst into life on Friday and Saturday nights, down by the boardwalk, in bars and nightclubs. The songs on the first two albums reflected that community through characters that were part real, part imaginary.

Carlin spends a lot of time in this book detailing the twists and turns in Springsteen’s relations with record companies, producers and publishers. Not surprisingly, he tells at great length the story of Bruce signing up with – and eventually spending two long years fighting a protracted legal battle to extricate himself from his contract with – his old buddy and New Jersey musician turned music publisher Mike Appel. Caplin quotes Springsteen:

Mike was for real. He loved music. His heart was in it. … That’s part of what attracted me to him, because it was all or nothing. I needed somebody else who was a little crazy in the eyes because that was my approach to it all. It was not a business. … It was an idea and an opportunity, and Mike understood that part of it very, very well.

It was Appel, after all, who got Bruce his Columbia Records contract. Two albums – not particularly successful in commercial terms – followed. But whenever Bruce listened to the first two albums he wasn’t satisfied:

All he could hear were the things he wished he’d done differently. The overstuffed lyrics, the stilted sound, the distance between what he needed to say and what came out of the speakers.

Springsteen’s notorious perfectionism is revealed in Carlin’s account of the grim and tortuous process of recording the next two albums – Born to Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town. It was a saga of ‘unplayable parts, unfixable mistakes, and unmixable recordings’, hours and hours, days and weeks of driving himself and members of the the band to exhaustion, and frustration: ‘the hardest thing I ever did’.

This is the period when Jon Landau enters the story – first with his historic review of a Springsteen show in Boston in May 1974 in which he exclaimed that he had seen ‘rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen’, adding:

Springsteen does it all. He is a rock’n’roll punk, a Latin street poet, a ballet dancer, an actor, a joker, bar band leader, hot-shit rhythm guitar player, extraordinary singer, and a truly great rock’n’roll composer. He leads a band like he has been doing it forever.

Landau’s endorsement was critical for Springsteen’s standing with CBS – the ‘rock and roll future’ line was appropriated by CBS in marketing Springsteen. More importantly, it led Springsteen to seek out Landau as a sounding board for his ideas as he prepared his next album. Born to Run made Springsteen a star, and Landau’s contribution was so great Springsteen decided he would be the man to guide him through his career as manager and producer – not just his right-hand man, but his right hand.

Carlin describes in some detail the Born to Run campaign run by CBS ‘like a D-Day invasion, with multiple forces poised to attack in calibrated waves’. Central to the campaign were the posters that featured Springsteen, back to the viewer, ‘bearded, curly-haired … looking like a poet biker in his black leather and jeans’, Elvis button on his sleeve, clutching a weathered Fender and a pair of Converse sneakers hanging from the guitar neck’.

Carlin describes the album cover, with Bruce leaning on saxophonist Clarence Clemons’ shoulder, as ‘the visual union of Elvis, Dylan, and Marlon Brando, with a touch of Stagger Lee looming over his shoulder for bad-ass measure’.

Carlin tells the familiar story of Springsteen being conflicted over the hype – it just got in the way of the reality and authenticity of what he was trying to express. For Springsteen the problem was exemplified by his arrival in London in November 1975 to find the capital plastered with posters on which Columbia had featured Landau’s ‘future of rock ‘n’ roll’ quote. Before the show at the Hammersmith Odeon, he ripped down all the posters he could find.

Carlin describes how Bruce gave in to some of the marketing pressures, compromising on aspects of the packaging and selling of Born to Run, though he did resist the idea for a shorter, radio-friendly edit of the single. At this point, too, he rejected stadium shows, even though the album’s success meant that the theatre venues that he’d barely filled months before were incapable of holding the audiences that now craved to see and hear him.

Despite the hype, in Carlin’s words, ‘Born to Run lived up to every promise ever made about Bruce Springsteen’:

From the breezy opening moments of ‘Thunder Road’ … the album stood as a summary of the previous twenty years of rock ‘n’ roll, a portrait of the moment, and the cornerstone of a career that would reflect and shape the culture for the next twenty years, and the twenty to follow. ‘It was the album where I left behind my adolescent definition of love and freedom,’ Bruce wrote. Born to Run was the dividing line.’

There follows the tortuous story of Springsteen’s infamous legal battle to escape from his contract with Mike Appel, a struggle that signified Bruce’s determination to retain complete control of his work. It would be two years before he was able to record a follow-up record.

When that album – The River – finally appeared, Springsteen was doing it again: passing on songs that he deemed too pop, too lightweight. ‘Because the Night’ and ‘Fire’ were tossed to others to make into hits – almost, even, ‘Hungry Heart’. Steve Van Zandt and others finally persuaded him out of that one, and it became the breakthrough single that lifted The River to the top of the album charts in autumn 1980.

Carlin rightly describes The River as an album that combines ‘the simple joys of rock ‘n’ roll’ while tracing ‘the human toll of economic and social inequity’. The River was also the album where Springsteen first attempted to write about the commitments of home and marriage. In the title song, Springsteen takes the story of his brother in law and sister Ginny who had fallen on hard times during the recession of the late ’70s, and turns it into something mythical:

The story of a young couple bound – by an accident of teenage conception, social expectations, and the absence of opportunity – to the same working class grind that had consumed the lives of their parents, and their parents’ parents. [It was] a word-for-word description of the life that Bruce’s sister Ginny had lived since her accidental pregnancy, at eighteen, and early marriage.

In his book, Carlin traces Springsteen’s growing commitment to questioning the American dream. In the words of ‘The River’, is it a dream, a lie, or something worse? He quotes Bruce as saying that, as a child, he heard little talk of politics in his neighbourhood, but does recall coming home from school one day and asking his mother whether they were Republican or Democrat: ‘She said we were Democrats, because they’re for the working people.’ Now he was reading American history, and had been particularly affected by Joe Klein’s Woody Guthrie: A Life and Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, both of which, like the unedited version of Guthrie’s ‘This Land Is Your Land’ which Springsteen had begun performing in his shows, offered a portrait of the underside of the American dream.

Bruce had also read Born on the Fourth of July, the memoir of the maimed Vietnam vet and anti-war activist Ron Kovic, and now began performing benefits for the Vietnam Veterans’ organization. It was around this time, too, that – as Ronald Reagan took over the American Presidency – Bruce began to feature at his concerts spoken introductions to certain songs that drew attention to the America of the vulnerable and downtrodden, combined with personal reminiscences of his own blue collar upbringing.

This is, perhaps, the abiding impression left by Carlin’s survey of Springsteen’s career: the sense of a man who has, right from the outset, formed a clear perception of where he stands in relation to music and his life and times:

I had an idea, and it was an idea that I had been working on for several records … through Nebraska, The River, Darkness, and right there on Born to Run. I was a strange product of Elvis and Woody Guthrie …I was fascinated by people who had become a voice for their moment. Elvis, Woody Guthrie, Curtis Mayfield, Bob Dylan, of course. I don’t know if I felt I had the capacity for it or just willed my way in that direction, but it was something I was interested in. Probably because it was all caught up in identity. You cannot figure out who you are if you don’t understand where you came from, what were the forces that work on your life as a child, as a teenager, and as a young man. What part do you have to play? How do you empower yourself?

With the trio of albums that began with The River and continued with Nebraska and Born In The USA, Springsteen’s reputation as the ‘blue collar troubadour’ was sealed. Carlin’s account demonstrates very clearly that there has been nothing happenstance about this. Each step of the way (perhaps only with the exception of a period in the 1990s) Springsteen has had a clear sense of his course and has kept to it. Steering between the poles of majestic stadium anthems and the quiet reflections on the American social fabric revealed on albums such as The Ghost of Tom Joad, he has become the embodiment of the American experience.

So much so, according to Carlin, that reading the New York Times obituaries of those killed on September 11, Springsteen was struck by how frequently his name was mentioned. Thomas H Bowden Jr, of Glen Ridge, NJ, was ‘deeply, openly, and emotionally loyal to Bruce Springsteen’. Christopher Sean Caton, of Glen Rock, NJ, was a Kiss fan as a boy. ‘But he soon moved on to Bruce Springsteen.’ After his death, his sister ‘found 35 ticket stubs to Springsteen concerts in his bedroom’. And on it went. Springsteen was so moved, Carlin writes, that he called up many of the victims’ families to offer his condolences.

More than any other contemporary artist, he had made himself synonymous with the cause of the common man; a fellow traveller on the same path trod by Woody Guthrie, John Steinbeck, Mark Twain and Pete Seeger.

And always there is that dedication to precise storytelling. On albums like Nebraska and Tom Joad Springsteen’s voice disappears into the voices of those he has chosen to exemplify the American story. In ‘Galveston Bay’, for example, off the Tom Joad album, Springsteen gets to the nub of the ironies and deadly tensions pursuant on American men being sent by their government to fight men in Vietnam required to do the same. The song originally had a violent ending, Bruce noted in Songs, but it began to feel false. ‘If I was going to find some small window of light, I had to do it with this man in this song.’

The song asks a question. Is the most political act an individual one, something that happens in the dark, in the quiet, when someone makes a particular decision that affects his immediate world? I wanted a character who is driven to do the wrong thing, but does not. He instinctively refuses to add to the vioolence in the world around him. With great difficulty and against his own grain he transcends his circumstances. He finds the strength and grace to save himself and the part of the world he touches.

In the last decade it seems as if Springsteen has become, in the words of political analyst Eric Alterman quoted by Carlin, ‘sort of the president of an imaginary America – the other America, so the rest of the world could admire the country the way they wanted to, without having to accept the fact that Reagan or George Bush spoke for America’. By the late 1990s, as Carlin points out, Bruce had moved away from earlier reservations, and become increasingly explicit about his politics. But, writes Carlin, while his sensibility flowed largely from New Deal liberalism, his working-class idealism came with bedrock principles on the virtues of work, family, faith and community:

None of which would be considered partisan had the collapse of American liberalism in the late 1970s and 1980s not included a large-scale redefinition of mainstream values as being conservative. That Bruce neither accepted nor acknowledged the politicization of traditional values could be seen in his own work ethic and the symbolic communities he formed with the E Street Band and the fans who bought his records and attended his shows. And even when his songs decried ruling-class greed and the fraying of the social safety net, they still cam bristling with flags, work, veterans, faith and the rock-sold foundation of home and family. […]

Just as he’d synthesized gospel, rock ‘n’ roll, rhythm and blues, folk, jazz and carnival music into a sound that echoed the clamour of the nation, Bruce’s particular magic came from his ability to trace the connections that hold the world together, even when it seems to be on the verge of flying apart.

Bruce offers a solid and interesting account of the arc of Springsteen’s career. But, for all its emphasis on contracts, tours and recording sessions, it lacks argument or deep analysis of Springsteen’s work. The man himself offered more in the incomparable Songs. Carlin’s work is certainly very different to another book I have just begun reading – Ian Bell’s Once Upon a Time: The Lives of Bob Dylan. Now that’s a different kettle of fish entirely, consisting exclusively of sceptical analysis directed, not to reconstructing Dylan’s life (for Dylan is ‘a writer who turned himself into a character to give voice to other characters’) but to trying to work out ‘who the hell he really is’. But more of that in future.

If there is a recurring implicit theme in Carlin’s book, it is the question of integrity. From the start, Springsteen has set himself the alchemist’s task of transforming the lives of working class Americans into the gold of poetry and myth. More than that, he has consciously set out to remain true to his roots: a difficult – some might say impossible – task given that he is a fabulously rich and famous celebrity. But, on the evidence here, he has largely conducted himself with shrewdness, humility and generosity, never forgetting where he came from. He’s still riding that train in the company of saints and sinners, losers and winners, fools and kings, whores and gamblers, lost souls, the broken-hearted and sweet souls departed whose dreams will not be thwarted, whose faith will be rewarded:

You’ll need a good companion for

This part of the ride

Leave behind your sorrows

Let this day be the last

Tomorrow there’ll be sunshine

And all this darkness past

Big wheels roll through fields

Where sunlight streams

Meet me in a land of hope and dreams

This Train…

Hear the steel wheels singin’

This Train…

Bells of freedom ringin’

Thea Gilmore: on tour in New Brighton

In the Blue Room of New Brighton’s Floral Pavilion Thea Gilmore was explaining how she and partner Nigel Stonier had, for the last five years, organised a literature and music festival in their home town of Nantwich in Cheshire. ‘Anyone know the material for a fifth anniversary?’ she asked. One guy suggested bacon. ‘Er, no…but you can stay at my house anytime’, she responded. The answer is wood, and wood became the theme for the concert that Thea and her band gave at this year’s festival: every song had to be wood-related, and it fell to Thea to sing an old German folk song made famous by Elvis Presley.

‘Wooden Heart’, sung solo by Thea midway through Sunday night’s show in New Brighton, was just one of the spine-tingling highlights of a superb concert; to hear it was worth the price of admission alone. She took the song at a slower pace than Elvis and scoured it clean of the jaunty, tripping rhythm of the original, paring it down to the intimate love song that lies at its core:

Can’t you see

I love you

Please don’t break my heart in two

That’s not hard to do

Cause I don’t have a wooden heart

Gilmore is an accomplished vocalist who can belt out a mean rocker or, as here, infuse a romantic ballad with a sensuous intensity. She did a creditable job of retaining the original German words sung by Elvis a year after he had completed his military service in Germany:

Muß i’ denn, muß i’ denn

Zum Städtele hinaus,

Städtele hinaus

Und du mein Schatz bleibst hier

(Got to go, got to go,

Got to leave this town,

Leave this town

And you, my dear, stay here.)

Earlier, Thea Gilmore had arrived on stage with her band, comprising guitarist, producer and partner Nigel Stonier, Che Beresford on drums, Alan Knowles on acoustic bass and accordion and Tracy Bell on keyboards. On two numbers the band was augmented, and its average age considerably reduced, when joined onstage by six year-old Egan – Nigel and Thea’s eldest child – who wielded a child-size violin.

Gilmore had kicked off with ‘Contessa’ from 2008’s Harpo’s Ghost, and there were to be a fair few numbers from the extensive Gilmore back catalogue in the course of the evening – for as she informed us, after tours promoting albums of songs by Dylan and Sandy Denny, she was thrilled to be doing what she likes doing best, singing the songs that she writes herself. She’d thought long and hard about the songs she really wanted to sing, and had dusted off a fair few which have not been performed for years. She’s halfway through recording a new album, due out in the spring, and at the gigs there is very limited edition EP available, called Beginners – because it’s a sort of taster for the main course to follow. She did two numbers off the EP, and one completely new song which may, or may not, be on the next album.

There were no Dylan covers in this show, but there were two of the previously unpublished Sandy Denny songs that Gilmore was commissioned to set to music, which comprised the album Don’t Stop Singing and were featured in the tribute show that toured the country this summer, The Lady: A Homage to Sandy Denny. Here she featured ‘Don’t Stop Singing’ and the Olympic summer single ‘London’.

Following the pen-portrait of an unwelcome reminder of a dissolute past in ‘Contessa’, we were treated to Thea’s angry and bitter portrayal of political arrogance in ‘God’s Got Nothing On You’ before she presented a song off the new EP, ‘Beautiful Hopeful’, all about the tribulations that await young musicians entering today’s music business. A little later Thea talked at some length about the process of making an album: always having too many songs, finding that after a while a dozen or so songs seem to chime together, leaving many more to be sadly cast aside. This was by way of an introduction to one of those songs – ‘The Amazing Floating Man’ – that appears on the new EP. Thea half-apologetically presented the song as being about the banking crisis; it was a solo a capella performance that lifted the hairs on back of your neck:

Roll up, roll up

For the best show in town

See him balance the books

As the markets crash down

And he never does much

But he does what he can

The Amazing Floating Man

By way of complete contrast (and you do get that with Thea – her songbook displays a tremendous variety of mood and material) we were treated us to a lively performance of the raunchy ‘Teach Me To Be Bad’: as she said, a song that ‘celebrates sex and the little devil in all of us’:

If I were coming off the rails

Dropped my eyes and dropped my dress

Would your moral stand prevail

Or would you fold like all the rest

Ooh ain’t we got fun

Ooh let’s come undone

I said one two well hand me a light

Oh three four I don’t wanna be right

By way of contrast, another new song from the EP, ‘Me By Numbers’ carried the refrain:

I can be a good girl

I can be a queen

I can be a soldier

I can be the thinking man’s dream

I can be a warrior

I can be the eye of the world

But most of all

I can be a good, good girl

Thea Gilmore grew up in Oxfordshire, her interest in music developing from listening to her father’s record collection, which included Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and The Beatles. She began writing poetry at the age of 15 as a way of coping with the divorce of her parents, and got an early start in the music industry, working in a recording studio and recording her first album Burning Dorothy as a teenager in 1998. In the following four years she released three more albums that earned her a growing critical reputation, but no chart success. It was around this time that I first discovered her songs: I remember listening repeatedly to Rules for Jokers, her third album that had standout tracks such as ‘This Girl Is Taking Bets’ and ‘Things We Never Said’, on the drive to and from work in 2001.

That album also included a song called ‘Inverigo’ that I could never really figure out: it had a lovely melody, but the meaning of some of the lines, and particularly the title, always puzzled me. On Sunday night, introducing the song to the audience in the Blue Lounge, Thea solved the mystery. She wrote ‘Inverigo’ in Italy, in the town of the same name; she was there with her partner, Nigel Stonier, who was recording an album. Though the trip, for her was ‘little more than a jolly’, at the time she needed to convince a record company that she had songs worth backing. ‘Inverigo’ was written in the company offices, they liked it, and she got a contract. After the concert, as Thea signed my copy of her new EP, I explained how that title had mystified me for a decade or more. ‘Well, there you go’, she replied, ‘puzzle solved’.

We are running from storms of our youth into more of the same …

We are free as the wind through the trees or so we are told …

In the last 15 years, Thea Gilmore has produced another ten albums, and has established a reputation as one of Britain’s leading songwriters. Though they can be a little uneven, each of her albums contains at least one gem that ranks alongside the work of the best lyricists. Joan Baez recognised her worth, picking up on ‘The Lower Road’ from Liejacker, and recording her version of the song on The Day After Tomorrow, and inviting Thea to join her tour.

After she recorded ‘I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine’ for a Dylan covers CD for Uncut Magazine in 2002, the accolades poured in, including one from Bruce Springsteen who, on encountering Gilmore backstage at a 2008 concert, showed his appreciation for the track, calling it ‘one of the great Dylan covers’. For, alongside her own songwriting credentials, Thea Gilmore is also a gifted interpreter of songs written by others. Some of these are to be found on Loft Music, an album of cover versions she put out in 2004; it includes wonderful interpretations of songs as varied as Pete Shelley’s ‘Ever Fallen in Love’, John Fogerty’s ‘Bad Moon Rising’, the great Phil Ochs song ‘When I’m Gone’, and ‘Buddy Can You Spare a Dime’. Other favourites include great versions of Pete Burns’ ‘You Spin Me Round’, Yoko Ono’s ‘Listen The Snow Is Falling’ and Springsteen’s ‘Cover Me’. And then of course there is her album of songs by Sandy Denny, and her recreation of Bob Dylan’s album John Wesley Harding.

I have my own strong favourites from her own compositions; one that I always hope she will sing live is ‘Old Soul’, and she did not disappoint on this occasion. When we hear a song it may have a personal meaning that can differ from the writer’s original intent. I listened to ‘Old Soul’ a long time before I became aware that old souls are those that have experienced several previous incarnations from which they have gained greater wisdom. On this video clip, Thea introduces the song, talking about how it was written while she was pregnant, and how the lyric’s meaning for her was related to the imminent birth of her child:

Setlist

- Contessa

- Don’t Stop Singing

- God’s Got Nothing on You

- Beautiful Hopeful

- Red White and Black

- Teach Me To Be Bad

- The Amazing Floating Man

- Me By Numbers

- Old Soul

- Roll On

- You’re the Radio

- Inverigo

Encore:

- Are You Ready?

- Goodbye My Friend

See also

Bruce in Manchester: standing shoulder to shoulder in hard times

The rain was lashing down so hard that the windscreen wipers could barely cope as I drove over to Manchester to see Bruce Springsteen’s show at the Etihad Stadium yesterday with an old friend who, at the last minute, acquired a pair of tickets from someone unable to go, and had graciously offered one to me.

What were we letting ourselves in for, we wondered, as the radio gave news of chaos as the deluge hit the Isle of Wight Festival, and flooding across the north as a month’s-worth of rain fell in 24 hours. In Liverpool, as we left, came news that the annual Africa Oye Festival had been cancelled after the stage had begun to sink in waterlogged ground at Sefton Park, and was declared unsafe.

Well, Bruce is The Boss, and he sorted it…minutes before he and his 16-strong band came on stage at 7:15, the rain stopped and, apart from a couple of brief showers later on, no rain fell for the next three and a half hours of the show.

There was no messing about: the band tore into the defiant opening chords of Badlands with a powerful energy that was maintained through the entire show, only pausing for breath during a brief interlude when Bruce sat alone at the piano to play The Promise.

Let the broken hearts stand

As the price you’ve gotta pay

We’ll keep pushin’ till it’s understood

And these badlands start treating us good

‘Decline, exploitation, war and death all receive an airing … ennobled into fist-punching entertainment,’ wrote Kitty Empire in her Guardian review of the show at Sunderland’s Stadium of Light three nights ago. That is the abiding impression left by this show for me, too. For much of concert, Springsteen’s choice of songs traced a distinct thread, one that raged against the injustices and betrayals of these hard times: the destruction of the material lives of ordinary working men and women, the promise of a better life and the dreams of personal fulfilment crushed by ‘robber barons and greedy thieves’ who ‘ate the flesh of everything they found’ and whose crimes ‘have gone unpunished’.

But Springsteen always ensures that his audiences go home spiritually lifted and with a vision that, standing ‘shoulder to shoulder and heart to heart’ we will one day rise up and leave our sorrows behind:

And all this darkness past

The characters and stories in Springsteen’s songs may be vivid portrayals of ordinary men and women doing their best to get by in a tough world, but the language, the imagery, is intensely spiritual – indeed, as is apparent on his new album, Wrecking Ball, increasingly religious, as the songwriter seems to draw on the deep well of his Catholic raising (as does Patti Smith). Part way through a rendition of My City of Ruins drenched in gospel, Springsteen roared, ‘can you feel the spirit tonight? Kitty Empire again:

Modern-day mass events – gigs, sporting fixtures and political rallies – can’t help but echo many of the ancestral dynamics of faith gatherings. And while most rock’n’roll makes liberal use of religious metaphors, there is a blatant revivalist tinge to tonight’s show, which borrows heavily from soul and gospel. Land of Hope and Dreams turns into People Get Ready. Lyrically, we are never far from Biblical language – a valley, or a mountain; Springsteen takes us down to The River, to some of the biggest cheers of the night, then takes us up to The Rising…

In another review of this tour, Evelyn McDonnell wrote in the LA Times:

Springsteen has always been a killer showman, someone who’s closely studied the great acts of R&B (the Rev. Al Green and James Brown) and learned how to preach a story, milk a call-and-response affirmation, and play dead then get on up. But increasingly, the gospel roots of this soul man have made themselves manifest. It seems like this Catholic son has been spending time in black churches.

‘Hard times come, hard times go’ is the phrase, delivered as a shamanic incantation part way through the song Wrecking Ball. Springsteen’s songs always have been a powerful combination of hard times and joy, but in these times and in this show that blend was paramount. The first six songs all expressed the rage and perseverance that ran like a thread through this show: Badlands was followed by a sequence of powerful songs, beginning with No Surrender, reprised from Born In The USA:

No retreat, baby, no surrender

Then continuing with a trio from the new album Wrecking Ball: We Take Care of Our Own,Wrecking Ball, and Death to My Hometown. I was a bit lukewarm about some of the songs when the album first appeared, but performed live in a stadium setting these are powerful anthems. I understand better now what Springsteen is attemting to do beneath the surface patriotism and flag-waving of We Take Care of Our Own:

From the muscle to the bone

From the shotgun shack to the Superdome

We needed help but the cavalry stayed home…

Where’s the hearts, they run over with mercy

Where’s the love that has not forsaken me

Where’s the work that set my hands, my soul free

Where’s the spirit to reign, reign over me

Where’s the promise, from sea to shining sea

Wrecking Ball, written in protest at the demolition of Giants Stadium, is now presented as a metaphor for the destruction wreaked on communities by financial institutions,culminating in that incantation of the phrase, ‘hard times come, and hard times go’:

And all our youth and beauty, it’s been given to the dust

When the game has been decided and we’re burning down the clock

And all our little victories and glories have turned into parking lots

When your best hopes and desires are scattered through the wind…

And hard times come, and hard times go

And hard times come, and hard times go

Death To My Hometown is as furious and fierce as it gets:

They left our bodies on the plains, the vultures picked our bones …

So listen up, my sonny boy, be ready for when they come

For they’ll be returning sure as the rising sun

Now get yourself a song to sing and sing it ’til you’re done

Yeah, sing it hard and sing it well

Send the robber barons straight to hell

The greedy thieves who came around

And ate the flesh of everything they found

Whose crimes have gone unpunished now

Who walk the streets as free men now

They brought death to our hometown, boys

But if one song stood out in this opening sequence, it was My City of Ruins, a track that I’d almost forgotten. It dates back twelve years, but took on a different meaning after September 11, and as a result it was added to The Rising. But now, post-recession, it regains its original sense. This was a tremendous performance, with Springsteen pushing the gospel exhortation, ‘Come on, rise up’, to the limit:

like scattered leaves

The boarded up windows

The hustlers and thieves

While my brother’s down on his knees

My city of ruins

Come on rise up!

The mid-section of the show consisted of a cavalcade of upbeat numbers, beginning with Spirit in the Night and a rare outing for The E Street Shuffle (with a superb jazzy intro), and several welcome rockers from The River: Two Hearts, You Can Look (But You Better Not Touch), Out on the Street, as well as the title track itself, with its fearful challenge:

Or is it something worse?

Darlington County was peeled off Born in The USA (to be followed later, in the encores, by Bobby Jean and Dancing In The Dark). Waiting on a Sunny Day came just as rain began to fall for a few minutes.

The main theme returned with a trio of songs from the new album: Jack of All Trades, Shackled and Drawn, and the inspirational Land of Hope and Dreams, with its invocation ‘This train’ rising to a crescendo:

And I’ll stand by your side

You’ll need a good companion now

For this part of the ride

Leave behind your sorrows

Let this day be the last

Tomorrow there’ll be sunshine

And all this darkness past

Jack of All Trades seems at first a quiet song out of the mouth of a quiet man, but ends with the threat, ‘If I had me a gun, I’d find the bastards and shoot ’em on sight’:

Brings a hard rain

When the blue sky breaks

Feels like the world’s gonna change

We’ll start caring for each other

Like Jesus said that we might

I’m a jack of all trades

We’ll be alright

The banker man grows fat

Working man grows thin

It’s all happened before

And it’ll happen again

It’ll happen again

It’ll beg your life

I’m a jack of all trades

Darling, we’ll be alright

Shackled and Drawn rails against a world gone wrong:

It’s still fat and easy up on bankers hill

Up on bankers hill the party’s going strong

Down here below we’re shackled and drawn

Pick up the rock, son, and carry it on

Trudging through the dark in a world gone wrong

The Promise and The Rising were in there, too:

The fight that you can’t win

Every day it just gets harder to live

The dream you’re believing in …

The promise is broken, you go on living

It steals something from down in your soul

There isn’t a Springsteen song that doesn’t, in the end, create spiritual uplift. But on this night, he seemed to demarcate sections of the show to different moods: apart from a sequence of rockers from The River album, he reserved the uplifting, crowd-rousing songs mainly for the lengthy encore, with unavoidable numbers such as Thunder Road, Born to Run and Dancing In The Dark. The encore set opened with the most uplifting song off Wrecking Ball, We Are Alive:

To stand shoulder to shoulder and heart to heart

Springsteen boasts an augmented E Street Band on this tour – 16 members, including old stalwarts Roy Bittan (piano, synthesizer), Nils Lofgren (guitar, vocals), Patti Scialfa (guitar, vocals), Garry Tallent (bass guitar), Stevie Van Zandt (guitar, vocals), Max Weinberg (drums) and Charlie Giordano (keyboards). They are augmented by new recruits such as Soozie Tyrell (violin, guitar) and a tremendous brass section, including tuba, trumpet and trombone. But the most crucial new guy is Jake Clemons, the nephew of the late Clarence Clemons, whose shoes he has filled effortlessly.

But Clarence is missed deeply; during My City of Ruins, Bruce took a roll call of the band, asking, finally, ‘Are we missing anyone tonight?’. Everyone in the crowd knew to what he was referring: not just the loss of Clarence, but also organist Danny Federici, who died in 2008.

Later, during the encore, came the most moving moment: during the climactic Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out, at the line, ‘When the change was made uptown and the Big Man joined the band’, Springsteen stopped the music. For several minutes Springsteen held up his microphone, urging the crowd (who really didn’t need any urging) to clap, roar, cheer or cry as images of the Big Man’s career flashed up on the giant screens. It was rock ‘n’ roll catharsis. It was beautiful.

At 62, Springsteen can still strut his stuff – he’s insanely active for someone his age, powering through the show non-stop for nearly four hours. He knows he’s old enough to be granddad to a large section of the crowd (that age profile was pleasing), and makes a point of emphasising it with a knowing grin in Dancing in the Dark when he comes to the line

there’s a joke here somewhere and it’s on me

There’s a bit of a performance, too, halfway through the encore when Bruce makes out that he’s completely knackered, collapsing to the stage and lying flat out as Steve Van Zandt tries to revive him by drenching him with a huge spongeful of water.

Earlier, just as the rain returns for a brief moment, Bruce goes straight into Waiting on a Sunny Day, with its opening line, ‘Well it’s raining…’.and then urges a young boy to join him on stage to sing a chorus or two.

This, and other moments, drove home what a great showman Bruce is. During Dancing in the Dark, he replicates the famous video at the time of the single release by having a couple of young women pulled on stage to dance alongside him, before each receiving a hug and a kiss. What a memory to take home from a show that was powerful, emotional and memorable for all of us.

The full setlist was:

- Badlands

- No Surrender

- We Take Care of Our Own

- Wrecking Ball

- Death to My Hometown

- My City of Ruins

- Spirit in the Night

- The E Street Shuffle

- Jack of All Trades

- Atlantic City

- Prove It All Night

- Two Hearts

- You Can Look (But You Better Not Touch)

- Darlington County

- Shackled and Drawn

- Waiting on a Sunny Day

- Save My Love

- The Promise

- The River

- The Rising

- Out on the Street

- Land of Hope and Dreams

Encore:

- We are Alive

- Thunder Road

- Born to Run

- Bobby Jean

- Cadillac Ranch

- Dancing in the Dark

- Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out

- Twist and Shout

These video clips are from other performances on the 2012 tour, but I’ve chosen them because they are high quality – and capture a few of the high points of what is clearly a crafted show that has retained certain key elements on every night of the tour:

Badlands – Madison Square Garden on 6 April

Waiting On A Sunny Day on 17 April in Cleveland

Tenth Avenue Freeze Out in Boston on 26 March 26 with tribute to Clarence Clemons

And here are two additional nuggets that offer further revealing glimpses of the man. First, at his Berlin concert, Bruce performed When I Leave Berlin, a song from the 1973 album by British folk musician Wizz Jones:

When morning comes and I’ll leave Berlin

My mind is turning

My heart is yearning

For you and Berlin

Here today but the wall is open call out the soldiers and the guns

Here today the gates are open mothers are in the arms of their sons

When morning comes and I’ll leave Berlin

I’ll know for certain I am a free man When I leave Berlin

And finally, the other week, Springsteen inducted Jackson Browne into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with a fine speech that ended with this passage:

In seventies, post-Vietnam America, there was no album that captured the fall from Eden, the long, slow after-burn of the sixties; it’s heartbreak, it’s disappointments, it’s spent possibilities better than Jackson’s masterpiece, Late For the Sky. It’s just a beautiful body of work. It’s essential in making sense of the times. Before the Deluge still gives me goosebumps and it raises me to cause. Late For the Sky, when those car doors slam at the end of the record, they still bring tears. And there was no more searching, yearning, loving music made for and about America at the time. […]

Jackson’s influence and his voice has always been his own. He’s one of the true activist musicians I’ve ever known. World In Motion, Looking East, Lives In the Balance, he followed his muse wherever it took him. Risked his, and he paid whatever the cost. He’s long put his mouth, his money, and his body where his politics are. Lives In The Balance sounds more urgent today than it ever did. […]

Listen to the chord changes of Rock Me On the Water and Before the Deluge, it’s gospel through and through. Now I always thought that in our fall from Eden, besides the strains of physicality and the bearing of earthly burdens, our real earthly task was that an unbridgeable gap, or a black hole was opened up in our ability to truly love one another. And so our job here on earth, the way we regain our divinity, our sacredness, and our general good-standing is by reconstructing love and creating love out of the broken pieces that we’ve been given. That’s all we have of human promise. That’s the way we prove ourselves in the eyes of God and facilitate our own redemption. Now, to me Jackson Browne’s work was always the sound of that reconstruction. So as he writes in The Pretender:We’ll put our dark glasses on, and we’ll make love until our strength is gone, and when the morning light comes streamin’ in, we’ll get up and do it again. Amen.