We have been entertained these past few days by the busy bustle of spring among the birds in our garden: a blue tit has found a hole in the sandstone wall and flies back and forth carrying nesting material, disappearing inside what should be a safe and warm shelter for its chicks, while a pair of magpies sift through the flower beds and fly off with beaks laden with twigs and leaves. Continue reading “Spring again, and our neighbours are restless”

Tag: birds

A woodpecker skirmish in the park

This is the time of year when the morning dog walk in Sefton Park is accompanied by the loud drumming of the Great Spotted Woodpecker. It’s a handsome bird when you catch a glimpse of it, either clinging to a tree trunk or flying from tree to tree in a flash of black, white and red. This morning I heard a commotion in the branches above me and saw something quite remarkable.

Since the 1950’s these birds have become increasingly common in parks and gardens throughout Britain. Once you have spotted one, they are easy to identify, being predominantly black and white, with a patch of red at the base of the body. You can distinguish males from females because the adult male has a small red patch on its head (juvenile birds exhibit a larger red patch that later disappears). But in spring their presence is usually betrayed by the sound of their drumming.

Although many people assume that they’re hearing the sound of a nest being drilled, that may not be the case, at least early in the season. In February, before the onset of the breeding season, the male woodpecker drums to signal for a mate. Selecting a hollow tree or dead branch with promising resonant qualities, he taps rapidly on the bark with his bill, making a rattle-like drum roll that is startlingly loud and carries for a considerable distance through woodland. Males not only drum in order to attract a mate – throughout the year they will continue to drum to proclaim their territory. Each male has his own drumming sequence and stops to listen to the replies of males nearby.

The drumming’ is the sound the birds make as they hammer their hard bills against the trunk of a tree. I’ve often wondered how the bird can do this repeatedly without doing itself serious brain damage. Here’s the answer, given on the British Trust for Ornithology website:

Hitting a solid tree with your beak so hard that splinters fly ought to cause the brain to rotate in the way that causes concussion in Man. Not a bit of it. The evolution of the bird’s drilling equipment has provided very sophisticated shock absorbing adaptations involving the way that the bird’s beak joins the skull. The stresses are transmitted directly towards the centre of the brain and do not cause the knockout swirl.

The beak is used like a combined hammer and chisel to drill into trees and branches and carve out deep nest holes. When woodpeckers hammer into wood to get at grubs they also have another anatomical adaptation designed to help them feed. The roots of their tongues are coiled round the back of their skulls and can be extended a prodigious distance to harpoon insect larvae in their tunnels.

Once a couple have paired off, the nesting hole, neat and round, is bored in soft or decaying wood horizontally for a few inches, then perpendicularly down. At the bottom of a shaft, usually from six to twelve inches in depth, a small chamber is excavated and lined with wood chips. The female lays up to seven glossy-white eggs in the dark chamber, each parent taking turns to incubate the clutch and later feed the greyish, red-capped fledglings. The young leave after three weeks. The nest hole is rarely used again, though other holes are often bored in the same tree.

What I saw this morning, alerted by a commotion in the branches above, was the sight of two males skirmishing outside a freshly-bored hole. I stood and watched for several minutes as they went at it with a fair amount of ferocity. I assume that what I was seeing was one male attempting to take over the freshly-chiselled hole of the other.

Woodpecker is rubber-necked

But has a nose of steel.

He bangs his head against the wall

And cannot even feel.

When Woodpecker’s jack-hammer head

Starts up its dreadful din

Knocking the dead bough double dead

How do his eyes stay in?

Pity the poor dead oak that cries

In terrors and in pains.

But pity more Woodpecker’s eyes

And bouncing rubber brains.

– Ted Hughes, from Under the North Star, 1981

See also

- Great spotted woodpecker: BBC Nature page with some great Springwatch clips

- Great Spotted Woodpecker: BTO web page

- Great Spotted Woodpecker: audio recording of its drumming

Tim Dee’s ‘The Running Sky’: to live is to fly

They were simple things, but they gave me much pleasure. A flock of starlings twittering as they settle, disperse, and settle again on a row of trees in the cemetery where I’m walking with my dog. A raucous mob of sparrows, stirring up the next street as they trade news, insults, or whatever it is their racket signifies.

Both birds were once so common they were hardly worth remarking upon. Now, with numbers collapsing, both are the RSPB’s red list. In our garden, we hardly ever see either these days, yet some of my strongest childhood memories involve these birds. I loved the sparrows’ noisy gregariousness; they seemed to be everywhere you looked. On Cheshire evenings I’d stand transfixed as great columns of starlings made their way towards their roosts in nearby woods. Which is why those recent sightings filled me with such delight.

Birds. How we do love them. The most popular feature of Springwatch are, I’d guess, the live cams on the birds’ nests. In the park at this time of year, fellow dog-walkers and others share the latest news about the progress of newly-hatched goslings and cygnets. In any season, you might encounter someone peering into a bush, staring up into the branches of a tree, or simply standing listening to the morning’s avian chorus.

Why is this? One answer, I think, is that birds are our neighbours – and the neighbours’ comings and goings are always fascinating. And rather than play music loud like some neighbours, they sing – joyously and mellifluously. Rita caught this in a poem she wrote some time ago that I really like, called ‘From the Window’:

All day I watch the mistle-thrush at work

Building with twigs and grass borne piece by piece

To wedge in its wind-ridden tree-top perch

And endure a season only.

While the long-tailed tit in solitary grace

Is dancing with a feather on a stone

Determined to subdue its air-light line

To the contours of a spider-web spun home.

They will be our neighbours then this year

Whose singing will greet us when we wake at dawn

Stirred by the whispering, barely discernible sound

Of what we have built begin to crumble down.

Then there is the puzzle – and wonder – of migration. For sedentary humans the arrival or departure of migrating birds is a powerful indicator of the year turning as the seasons change. The return of the swifts to the skies above our avenue is an annual moment of joy. But where have they been?

Swifts, especially, birds that spend their whole lives in the air, epitomise another feeling we have when we watch birds – our earthbound envy at their freedom in flight. Townes Van Zandt might have been thinking of swifts when he wrote ‘To Live is to Fly’:

We got the sky to talk about

And the earth to lie upon.

Time is yours to take;

Some sail upon the sea,

Some toil upon the stone.

To live is to fly

Low and high,

Shake the dust off of your wings

And the tears out of your eyes.

Perhaps it’s because I have just finished reading Tim Dee’s miraculous book The Running Sky that these thoughts are uppermost in my mind. His book has been lying around the house for a couple of years, but I picked it up after reading a superb piece on Derek Walcott in the London Review of Books. As producer of the Radio 4 poetry series The Echo Chamber, he’d been to St Lucia with Paul Farley, doubling up as sound recordist). Both men are keen birdwatchers, and Dee’s piece is attentive to the species they were rubbing shoulders with on the island:

It’s odd, in a world fizzing with insects and furious hummingbirds, to hear Walcott speak with such affection about Edward Thomas and John Clare; odd to follow his gaze out to sea and hear him quote Walter de la Mare’s ‘Fare Well’ with its intimations of an English pastoral afterlife. When at the party Glyn Maxwell, or perhaps it was Paul Farley, asked him what it was to be a ‘Caribbean’ poet, he lapsed into silence, the chorus of insects and birds answering on his behalf. The two British poets were putting the questions as I held the microphone and watched the sound levels: the high-pitched calls of hummingbirds set the needles jumping – two species, the green-throated Carib and the Antillean crested, hard to see clearly because they move in a way quite unlike other birds and at such speed.

There were bananaquits too. As we were talking a few came close to us, not much bigger than hummingbirds, black above and yellow below, like birds zipped into bee suits, anxious, constantly on the move, making their thin quit call. We were being audited for our potential sweetness and the birds were disappointed. The bananaquit loves nectar, bowls of sugar on café tables, rotting fruit and anything fermented to around 4-6 per cent alcohol. It will happily come to a bar and sip at an untended beer, returning to tipple throughout the day with no ill effects. (Unlike parrots, which as Aristotle knew, have no head for alcohol: in Australia, where they binge on over-ripe pears, birdwatchers have seen them getting legless, Amy Winehouse-style, faltering on branches and plummeting from trees.) For a long time no one in avian taxonomy knew where to place the bananaquit, and it was bottled nicely in its own family. Recently it has been lumped in with the ungainly ‘pan-American tanager’ cohort. Although it is one of the commonest birds in the towns and villages of St Lucia, away from its syrups it cuts fast through open space and busies itself in the interior of leafy trees, making it tricky to get a good look at. You hear bananaquits almost continually, but their quits are often lost in the general pulse of grackles, crickets, cicadas, hummingbirds, mosquitoes and the wider vegetative buzz.

Tim Dee was born here in Liverpool in 1961, but grew up in Bristol. He has worked as a BBC radio producer for twenty years. The Running Sky was published to great acclaim in 2009, while his latest book, Four Fields, has been gathering positive reviews in the last few weeks.

At first sight, The Running Sky might not seem that special: a memoir of his birdwatching life presented in diary form, with a chapter for a different month in one birdwatching year (though not of any specific year). But this book is more – much more – than a twitcher’s tally (in fact, it’s not that at all). This is not just an account of one man’s love of birds and birdwatching. It is an open and deeply personal memoir in which he recalls significant moments in his life – recollections which spin off into meditations on the natural world which draw upon poetry, music and literature.

Even that doesn’t really do justice this beautiful book. Because it is Dee’s writing that makes this book a transcendent experience: it reads like an extended, perfectly formed prose poem. He is expressive in his descriptions of events and people in his life, and eloquent in expressing emotions and thoughts. Dee’s memories merge into one stream of conciousness as he braids accounts of observing bird behaviour in various places at home and abroad with recollections of his childhood, his parents (who encouraged his early obsession with bird-watching), and adult encounters. He begins in Liverpool, with the first bird he can remember. It was a swallow, and, he writes,’all swallows since have joined that bird appearing above me and flying on ahead’:

The first bird I can remember watching flew through the garden of the house where I was born. It was summer. I had just had my third birthday. I was pulling my red wooden train on its string; the train driver with his blue cap swayed a little, because the grass beneath was bumpy. We were in the back part of the big garden of the house – it was called Acresfield – on the outskirts of Liverpool. I steered carefully because we were going along a thin strip between furrows of turned soil where the old man who lived in the flat above us grew his vegetables. I concentrated to make sure that the train followed me and the driver – he had a column of blue painted wood instead of legs – didn’t wobble too much, topple over and roll from the train.

I heard shouting and I looked towards the noise: far across the wide lawn beyond the vegetable patch, the old man was leaning out of an open window and waving his arms like a bear. A year or so later when I met Mr McGregor in The Tale of Peter Rabbit I knew him already. The man at the window seemed too far away to be real, and though his voice must have been loud and angry, it grew thin and fell towards the lawn. But he was shouting at me and I didn’t like it, It was too much. I had to drop the string, abandon the train and driver, and flee.

I looked up for my mother, who was somewhere in the garden,and headed for the greenhouse at the edge of the vegetable patch. The path bulged around a water butt; I followed it and kept going towards a wide black space of dark, the opening of the garden shed. From behind me, over my head as I moved towards the dark, came a bird. It pulled up into the dusty black rectangle of the open doorway and disappeared inside. It was showing me the way. I followed it.

In the sunshine, the space seemed to be hung with a black curtain. I walked through it; the air cooled and the noises dimmed. The throat~catching smell of warm creosote came. Everything was still. My eyes liked the bandage of the dark. Then, with a suddenness that made me gasp, the swallow was there and gone, diving back into the bright. It called once as it left, its buzzing twitter like an electrical spark. I looked up through the murk and saw on a crossbeam a little mud pie with tiny sticks of straw poking from it. I forgot my train and the shouting.

That afternoon my father took me back to the shed so I could peer into the nest. Again, as we stepped into the dark, the swallow slipped over us; it was so close I could feel the air rub against me. On my father’s shoulders I raised my arms towards the nest, slowing and softening my reach as I felt for the bumpy balls of mud and the prickly stems. There were no young birds, or even any eggs yet. I couldn’t see into the cup, but let my fingers creep over its rim, feeling the smoothed lip and the feathers lining the tiny bowl. It was warm.

Some days later, I went to the shed but found it empty. On the hard ribbed concrete floor was a square mess of baby swallow, a miniature hooked beak, downy balding feathers, raised but useless open wings, dead half-meat beneath thin bat-skin.

I remember just these two scenes – one of calm and one of horror. I didn’t see the birds fledge any young; I had no concept of their departure. But I became a birdwatcher that summer. The swallows, their flight, their music, their stopped moments perched on wires or incubating their eggs, their nest – all this was somehow laid inside me, like iron in my blood, so that no swallow after Acresfield has been my first, but all swallows since have joined that bird appearing above me and flying on ahead.

A theme to which Dee returns frequently and compellingly is the mystery of migration. The autumn departures and spring arrivals of birds ‘have made a timetable in my life’, he writes.

To be deprived of an autumn, its chilling lift, its emptying blast, and all its atmospheres between, held indoors shuttered from the wind and the light, or exiled to the seasonless tropics, would be a kind of death. My children have been born, my parents have grown old, relationships have been made and foundered and made again, my work has flowered and soured and rallied – all these human adventures are what my life has been built from. Yet my years throughout have been rhythmically driven by the step up into spring and the swing away into autumn and the movements of birds through them. Comings and goings. Windfalls.

He records the passage of migrants in places as far-flung as Fair Isle (one of the first places in the world where passage birds were logged and studied, and where the mystery of migration began to be solved) to the plain before Troy, in western Turkey, where Dee encounters one of his favourite birds – the redstart, en route from Russia or Ukraine. The rusty red of the redstart’s tail reminds Dee that Aristotle thought that the summer redstarts of Greece turned into its winter robins.

Thinking of redstarts also reminds Dee of John Buxton who, while a prisoner of war in a German camp in Bavaria in 1940 observed a family of redstarts ‘unconcerned in the affairs of our skeletal multitude, going about their ways in cherry and chestnut trees’. When the next spring came, and the redstarts returned, he set out to study the birds during the hours he in the camp that he spent out of doors. The result was The Redstart, published in 1950 and, in Dee’s opinion ‘one of the finest bird books’. Dee writes:

His ornithology was good, but what makes Buxton’s book so unusual and distinguished is his beautifully expressed humility in the face of what he sees. Before the book has got under way he is saying he hasn’t really written a work of natural history at all: ‘These redstarts . . . I loved for their own sake and not for the sake of adding to men’s knowledge.’ His modesty, his gently expressed jealousy of the redstarts’ freedom, his assertion again and again that the birds might not be doing what he thinks they are – all make for remarkably tender science.

He quotes this passage from Buxton’s book:

I must be understood to refer only to my redstarts. […] My redstarts? But one of the chief joys of watching them in prison was that they inhabited another world than I; and why should I call them mine? They lived wholly and enviably to themselves, unconcerned in our fatuous politics, without the limitations imposed all about us by our knowledge. They lived only in the moment, without foresight and with memory only of things of immediate practical concern to them – which was their nesting hole, and which their path to it, where lay the boundaries beyond which they would not go; memory also, perhaps, of the way back when their one necessary urgent purpose was done, to the hot sun of Africa.

Throughout this illuminating book, Dee is alert not just to the details of the birds he is observing, but also to the various ways in which birds have inspired artists, poets and musicians. He notes, for example, that in May 1940, the same month that John Buxton was captured, Olivier Messiaen was imprisoned in Stalag VIIII-A at Gorlitz. It was there he wrote – and premièred – his Quartet for the End of Time, which features musical accounts of a blackbird (played on the clarinet) and a nightingale (the violin).

Thinking about prisoners who preserved their sanity by taking pleasure in the freedom of birds leads Dee to recall the strange and inhumane experiments conducted on swallows during the Cold War by the Soviet ornithologist, DS Lyuleeva. To determine the energy costs of birds’ flight, she caught swallows and swifts, deprived them of food to empty their guts, then sewed their bills shut so they couldn’t feed on the wing, and threw them back into the air. Later, the birds (or those that survived) were recaptured and had their mass losses calculated. As Dee dryly observes:

This episode suggested that considerable losses of weight, characteristic of swallows deprived of food for a long period of time, induce torpidity and subsequent death. Perhaps I am missing something, but this doesn’t seem a major scientific breakthrough – if a bird cannot eat it dies.

He goes on to draw a grim moral from these experiments, conducted in the 1960s on the Baltic shore of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia which was then a military zone and a heavily policed frontier of the USSR, with watchtowers and border guards – ‘and just a few permitted scientists from Leningrad stitching shut the beaks of swallows’. The people there were cut off from their shore, kept from their sea:

Declared out of bounds to ordinary people, the bow-line of sand became a slowly shifting northern desert. In a decade of concrete and iron, walls and wires, weaponry and rust, on a cold Soviet shore an ornithologist is sewing a thread through the nostrils of a swallow, a bird that had come freely into that pallid spring from its winter in the skies of South Africa, another country then savage towards its own people. It is hard not to see some human envy, unspoken but deep, at work in these experiments. The birds come and go, we are stuck here, let us catch them and tie them to us.

Or, as one poet put it (when thinking about dogs):

I am compelled to conclude

That man is the superior animal.When I consider the curious habits of man

I confess, my friend, I am puzzled.

– Meditatio by Ezra Pound

Another striking feature of The Running Sky is the way in which Dee repeatedly slides between birdwatching episodes and moments in his personal life. Perhaps the most vivid example comes in the chapter in which he remembers his childhood in Bristol, when a daily paper round would take him past the Avon Gorge where he would watch birds as they coped with the ‘wind machine’ of the Gorge, ‘the bash and thrust of air funnelled and collected by its cliffs and slopes’ that made its own wind: ‘gusts, thermals and aerial maelstroms’. He watched jackdaws and other birds there, but there was always one kind of bird that was missing – the peregrine.

This chapter combines a brilliant analysis of the book about peregrines which has become a classic – JA Baker’s The Peregrine – and the afternoon when, as a twelve-year old on his paper round,’I saw a man jump into the Avon Gorge and I learned as deeply as seemed possible, then and now, that we cannot fly and we must make our escapes in other ways’.

Dee’s is the best discussion of Baker’s strange yet wonderful book that I have come across. It is a book, avers Dee, ‘the weirdness [of which] cannot be overstated’. ‘Blood-drenched and strewn with corpses’, Baker’s book is also:

A grounded man’s love affair with the airborne, a story told by a downed Icarus long after his fall, earthed, haggard and self-loathing, traipsing through marshes, crouching in ditches and lurking on field edges, and looking up before a greater creature.

The Peregrine is, Dee asserts, ‘nature writing’s Goya’. It was the greatest ‘and most needed’ bird book of his youth. Then, on his paper round one November afternoon and looking out for peregrines, he was cycling across the bridge over the gorge when a young man just in front of him

Turned his head to the right and glanced over his shoulder. Perhaps he saw me, maybe he didn’t. As he turned his head, he brought a cigarette in his right hand to his mouth and dragged on it; its tiny fire throbbed brightly back to me. Then, still walking, with the cigarette in his mouth, he put both hands on the wooden railing of the bridge to his left, and vaulted over the side.

The precision of the observation, written down now decades later, speaks of a birdwatcher’s accuracy – and of a horror that was burned into a young boy’s memory, and which would not leave the man. Dee writes how, ten years later, his breath faltered as he entered the building at Tring where the Natural History Museum’s bird collection is kept. There was something about ‘the hospital-clean corridors’,the ‘institutional quietness’ and the sense of ‘being in some giant tomb’ that took him back to the coroner’s courtroom in Bristol where he had been summoned to make his statement about the suicidal leap into the void.

For me, the finest chapter is that in which Dee describes dusk on the Somerset Levels at the winter solstice, as thousands of starlings arrive to roost. ‘Every evening’, he writes,

through the winters of the past few years, thousands, even millions, of starlings have come to sleep here. Eight million were counted, somehow, in one roost here a year or so ago. Th0′ may be the largest ever gathering of birds in Britain. Imagine Hyde Park Corner in failing light and the entire population of London arriving there from all points across the city.

By the time Dee arrives flocks of a hundred or more are already out on the Levels:

Local birds and arriving birds mixed, squabbling, feeding and talking. […] They seemed to be joining some necessary action. A call-up was under way.

That evening, summer was further off than it would ever be. Stowed sunshine from months ago was rationed, like the last grains of sugar in a siege. Its light and heat survived in only the flimsiest of things: the feathered seed heads of the reeds that engraved fine scratches onto the plate of the sky, and the tiny contact calls swapped between parties of long-tailed tits as they moved through the willow tops, living in the warmth of their own talk. Everything else was, or soon would be, a shade of black.

Tim Dee’s description of what follows is magnificent:

From all sides there were lines of starlings, in layers of about fifteen birds thick stretching for three miles back into the sky and coming towards the reed beds that surrounded me. They came out of the furthest reaches of the air, materialising into it from far beyond where my eyes or binoculars could reach in the murk. All flew with a lightly rippling glide, as if the net they were making of themselves was being evenly drawn into a single point in the reed bed.

Their arrival and accumulation had been eerily silent. From the early afternoon, first in the villages and then in the staging fields, there had been great noise. A collective telling and retelling of starling life rose through those hours of pre-roost talk to a complicated but loquacious rendering of all things – idiomatic adventure, mimetic brilliance and delighted conversational murmur. Once this annotation of the day was done, the birds grew quiet and lifted up and off to begin their thickening flights towards the roost.

There were thousands of mute birds around me, their wheeze and jabber left behind. Many thousands more were too far away to hear, but their calm progress towards the roost suggested they flew in silence. Closer, the only noise was of the flock’s feathers. As they wheeled and gyred en masse, the sound of their wings turning swept like brushes dashed across a snare drum or a Spanish fan being flicked open. The air was thick with starlings, inches apart and racked back into the darkening sky for a mile. Every bird was within a wing stretch of another. None touched.

A rougher magic overtook them as they arrived above the reeds. Great ductile cartwheels of birds were unleashed across the sky. Conjured balls of starlings rolled out and up, shoaling from their descending lines, thickening and pulling in on themselves – a black bloom burst from the seedbed of birds. One wheel hit another and the carousels of birds chimed and merged, like iron filings made to bend to a magnet. The flock – but flock doesn’t say anything like enough – pulsed in and out.

Dee is overcome by the scale of it all: to describe the flock is ‘like trying to hold on to a dream in daylight – it slips from me, it cannot be summoned except in fragments, and they cannot be transcribed’. Then he makes a remarkable comparison:

Try singing it. I thought of Thomas Tallis’s forty-part devotional motet Spem in alium from 1570. […] Could its eleven and a half minutes of singing light the black midwinter night and the black midwinter starlings?

Spem in alium doesn’t describe what the flock does. It is the flock. The music – unaccompanied singing, or rather singing that only accompanies itself – comes in, opening its throat before us, beginning with some tentative note on some frontier of sound, arriving into a space from a place without space, from far away. It might be one bird flying, or the sound of a wave beginning far out in the Atlantic. The sound catches and swirls towards us, becomes a striving, and folds into itself and floats and opens further with a beautiful frail young solo which twists my ears and then gives onto a landscape like the great heave of an abstract painting, making me think of Peter Lanyon’s sky masterpieces, as well as starlings hatching from the evening. It is huge and everywhere, but tilted and very close. And all along there is the strangest of pulses, a breathing, a flexing continuo, that rises into the heights…

Brilliant writing: the birds have become music; the music’s form consists of birds in movement.

In the touching ‘Afterword- Singing’ Dee recalls the time when, ten years old, he was kissed by a girl for the first time. But he ‘couldn’t kiss her back – a mistle thrush got between us’. Dee tells it with a mysterious lyricism:

A cold ragged day had begun without promise. The year had pulled into itself. Light came up but there was no sky, the blank space above looked as if it had been rubbed with a dirty cloth, a worn grey smear pushing over everything. It was Surrey and the weekend and I was bored. Autumn was over, Christmas a long way off.

My mother called me to the front room and pointed through the window. There was a girl standing on the road, at the bottom of our driveway, below the line of bare beech trees, looking up to the house. I knew her – it was Karen – and I knew straight away why she had come, but I wasn’t ready. My mother said she had already been there for a while and that I should go out to her. I didn’t want to but I did.

I opened the front door, starting down the gravel. It was about a hundred yards to Karen. As I walked I could see her lips moving, her mouth opening and closing. I couldn’t hear her because a mistle thrush had started shouting its song from somewhere high up in the trees. I heard the bird as you might hear a lighthouse – a voice on its own, powering away through the wind, a clean brittle shout of far-carrying pure song. It lit all quarters of the sky space with

short repeated stabbing notes that made me wince as if it were cold.Karen had come up through the hundred-acre hangar of trees … from where she lived, near our school. She was like a mistle thrush herself – lean, leggy, a little severe, with a short haircut and spectacles – and as I stepped closer, though I still couldn’t hear her, her lips moved and she seemed to be singing

the thrush’s song, as a troubadour might recruit an ‘auzel’. Love had brought her here, love of a kind, like the thrush. She and it were working against the season — it was November – the days were still shrinking back, but the bird was lighting the way to spring and Karen wanted to do the same.I couldn’t answer her – I was not even eleven, she was six inches taller than me, and it was all too soon. The thrush had stopped my ears. Karen smiled and tried again. She looked down sweetly to me, her head falling to her chest as if she’d been hung from a hanging tree. She steeled herself and said that she would go if I would let her kiss me.

She leant in and kissed me on the lips. The mistle thrush was directly above us, high up in the broom head of the bare trees. I felt it was singing into my skull, annealing my whole body with its bright, white music, heating me up and cooling me down. I followed Karen’s eyes as she looked up, and replied

with a peck on her cheek; it was all l knew. She turned and as I watched her cross the road and start down the path through the wood, the mistle thrush was still banging on, shouting after her.

The funny thing is that, although The Restless Sky received unanimous praise from the critics when it was published, if you go to the book’s page on Amazon and scroll through the reader reviews posted there, you’ll find many irritated and disgruntled comments. Along the lines of:

I imagine going birdwatching with him and decided that you just couldn’t walk 2 yards without some literary quote. Look it’s a Skylark, (ah yes Shelley said…) it’s a Carrion Crow (ah yes Shakespeare) shall we go in this hut (ah yes it reminds me of a Canaletto) – arrrggghhhh!

Or:

I only made the start of the third chapter before hurling it with some force against the wall. The inappropriate adjectives, the redundant metaphors, the flights of fancy!!!

I suspect there is a certain kind of birdwatcher who (like Chris Packham, perhaps) just wants the unadorned facts, and no poetic flights of fancy. But as Tim Dee points out somewhere in the book, both poetry and science can contribute to our appreciation of the natural world:

Science makes discoveries when it admits to not knowing, poetry endures if it looks hard at real things. Nature writing, if such a thing exists, lives in this territory where science and poetry meet. It must be made of both; it needs truth and beauty.

Simon Armitage, in The Poetry of Birds (co-written with Tim Dee) wonders why poets have written so many poems about birds. ‘Perhaps at some subconscious, secular level,’ he writes, ‘birds are also our souls’. He continues:

Or more likely, they are our poems. What we find in them we would hope for our work – that sense of soaring otherness. Maybe that’s how poets think of birds: as poems.

See also

The call of the river

Canada geese in flight. Photo by Philippe Henry

The day began, walking with the dog in the park, with a skein of geese flying overhead, a honking arrowhead of birds heading straight for the river. I don’t think there is any another sound that so lifts my spirits. By mid-afternoon, the sunlight slanting brightly in the avenue, I heard the call of the river too.

As if pulled by the same primordial force that drew the geese, I headed out of the city, beyond Speke and the airport to Pickerings Pasture. This is one of the best places to gain an appreciation of the breadth of the Mersey estuary, gouged and widened by glacial ice as it advanced south-eastwards and flooded as sea levels rose at the end of the ice age. Here, at high tide, the river makes a broad S-bend sweep from the pinch point of the Runcorn gap south and west along the Cheshire shore towards the silver towers and chimneys of Stanlow oil refinery, glinting in the late afternoon sun. Beyond lie the darkening outlines of the Clwydian hills.

The tide is running strongly toward the sea as, with the dog at my side, I set off to walk the short stretch along the river to the Runcorn bridge. It’s a walk that embraces wild beauty and big-sky views, whilst snaking around the fringes of the Merseyside edgelands with its arterial roads, industrial estates, retail distribution centres and mysterious industrial processes.

The starting point, Pickering’s Pasture Nature Reserve, symbolises this dichotomy. Until the 1950s the area was a salt marsh, grazed by cattle and home to wading birds and estuary plants. Then, for the next 30 years, the site was used as an industrial and household waste tip and a mountain of refuse rose on the salt marsh. But the land has now been reclaimed by Halton Borough Council, creating a haven for wildlife, covered by wild flowers, shrubs and trees and once again a place visited by resident and migrating birds. Surrounded by industry, it is a place of peace and quiet with magnificent views of the Mersey estuary.

We’re walking a section of the Trans-Pennine Trail here, encountering the occasional commuting cyclist who creeps up silently behind. Along the track the autumn abundance of this ‘mast year’ is apparent; a year when, as the Guardian’s Plantwatch noted a few weeks back:

Trees are weighed down with an astonishing crop of nuts. … A mast year includes all the other nuts of woodland trees – acorns, sweet chestnuts, conkers, hazel, ash, maple, lime and many others. … Berries have also appeared in a bonanza season that should make for good foraging. There are heaps of big blackberries, elderberries, bilberries, sloes, rowan berries and others.

There were still a few blackberries, battered by the wind and rain of the past two weeks, along with elderberries and rowan, and lots and lots of rose hips.

Along with all those easily-identifiable berries there was this unfamiliar (to me) large shrub with long thin leaves and bright yellow berries. I later identified it (I hope correctly) as Sea Buckthorn that gets its name from being largely confined to sea coasts where salt spray off the sea prevents other larger plants from out-competing it. The berries are an important winter food resource for birds, especially the fieldfare – a bird regularly sighted here by the volunteers of the Friends of Pickering’s Pasture.

The Pickering’s Pasture site was regenerated between 1982 and 1986 when Halton Borough Council reclaimed the land, safely covering the waste of the land fill site with a thick layer of clay. A little way along the river bank is this obelisk, erected on the site of an old navigational beacon that was used by shipping on the Mersey right up to 1971. The obelisk was constructed by men employed on the regeneration project.

One of the benefits of that scheme was the construction of the elegant white footbridge across Ditton Brook that rises somewhere around Netherley and flows through Ditton Marsh before joining the Mersey at this point. Before its construction, the idea of walking from Hale to Runcorn along the river must have been out of the question if you weren’t carrying waders.

The brook, edged with tidal mud that attracts many wading birds, winds through the low-level industrial units of Halebank Industrial Estate.

But, at the eastern end of the footbridge a staircase of steps leads to a very different view: turn your gaze towards the river and, at high tide you’re presented with a view of the broad sweep of the Mersey with Cheshire’s sandstone ridge rising up behind Frodsham on the far bank and the hills of Wales on the skyline to the west. The view is at its most impressive as sunset nears.

Walking on, the path is edged on the landward side by classic edgeland scenery: storage tanks, drainage ditches, railway arches and industrial units. We’re looking at the back end of the grandly-named Mersey Multimodal Gateway which, ‘if you’re into the movement and storage of goods’ – according to the group’s website – ‘is a unique piece of infrastructure with unrivalled features’. At one point the path runs right alongside a food processing plant that is both noisy and smells richly of some ingredient that might be used in the brewing industry.

Since I last walked this stretch a huge Tesco distribution hangar has appeared, while nearby there is an Eddie Stobart cold storage yard where a ceaseless procession of articulated lorries were returning from making the day’s freight deliveries.

By now the bridge is dominating the view, although to be accurate there are two: the more westerly rail bridge and the distinctive Runcorn-Widnes road bridge that carries the A533 over the River Mersey and the Manchester Ship Canal, opened in 1961 as a replacement for the Widnes-Runcorn Transporter Bridge which I remember crossing the Mersey on as a child.

At the foot of the railway bridge are the remains of an old dock, the walls constructed from the distinctive red sandstone of this region.

Returning along the path, I could make out the Manchester Ship Canal on the opposite shore, with what looked like another Eddie Stobart distribution facility adjoining it. Beyond loomed the sandstone crags above Frodsham.

As the sun began to set behind clouds to the west, a Ryanair flight made its descent towards John Lennon airport.

The western sky was bathed in a golden glow as the sun set beyond the Welsh hills.

Walking back I suddenly realised that I was not alone: above me, silent columns of seagulls leisurely made their way, following the river, headed for the sea. There were hundreds in any one batch, thousands strung out ahead of me moving towards Liverpool, and more coming on silently behind. I don’t know if this is a nightly movement towards roosting areas on the shore along the coastline of the Mersey Bay, or whether it was associated with the tide, running strongly towards the sea. Whatever it signified, it was a magnificent sight, making a perfect end to a day that begun for me with that honking skein of geese flying above me in Sefton Park.

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

– Mary Oliver, ‘Wild Geese’

See also

- Mersey Multimodal Gateway? Step this way: alternative take on the same walk by fellow local blogger Ronnie Hughes at A Sense of Place

- The Edgelands: a zone of wild, mysterious beauty

- A walk in the edgelands: along the Garston shore

- Walking the Mersey: Oglet shore

- Walking the Mersey: Dungeon to Hale Point

- Pickering’s Pasture: sunset on the Mersey

The goldfinch: symbol of salvation yet thrice-cursed, ‘enjailed in pitiless wire’

Yesterday I wrote about the connection between Donna Tartt’s new novel and the 1654 painting by Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch. That set me thinking about why Fabritius had chosen the bird as a subject for a painting, so I thought I’d consult the book I received as a birthday present recently: Birds and People by Mark Cocker.

What I found there proved to be fascinating. In a sense, Carel Fabritius was following a well-established tradition of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance of featuring a goldfinch in paintings, especially images of the Madonna and holy child. What mattered for these artists was not the accuracy of natural history but the bird’s symbolic or allegorical meaning. Cocker reckons that close on 500 paintings in this period included the goldfinch motif. In the case of the Madonna images, the bird often occupied a central place in the composition, perched on Mary’s fingers or nestled in Christ’s hands.

Detail from Taddeo di Bartolo’s ‘Virgin and Child’,14th century

‘Virgin and Child’, Florence, 14th century.

So what was it about the goldfinch that warranted its inclusion in hundreds of paintings? The answer lies in the bird’s plumage and lifestyle, which had produced in the medieval mind powerful symbolic associations. Cocker quotes the scholar Herbert Friedmann who wrote in The Symbolic Goldfinch (1946) of the ‘ceaseless sweep of allegory through men’s minds. They felt and thought and dreamed in allegories’.

Detail from ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ by Hieronymous Bosch, c1510: rampant allegory featuring an outsize goldfinch.

What did the individual feel, then, when they saw an image of a goldfinch? First, there was the bar of gold across the bird’s wings, a colour which, since the ancient Greeks, had been associated with the ability to cure sickness. Then there was the splash of red on the cheeks: as with the robin’s red breast this was a sign to medieval Christians that the bird had acquired blood-coloured feathers while attempting to remove the crown of thorns from while Christ was being crucified.

Finally, not only did thistles have a symbolic association with the crucifixion: thistle seeds are the staple food of the European goldfinch, and thistles were themselves regarded as curative (long credited, for example, as a medicinal ingredient to combat the plague).

John Clare, always observant of bird behaviour, noted the goldfinch’s preference for thistles in his poem, ‘The Redcap’ (an old country name for the bird):

The redcap is a painted bird

and beautiful its feathers are;

In early spring its voice is heard

While searching thistles brown and bare;

It makes a nest of mosses grey

And lines it round with thistle-down;

Five small pale spotted eggs they lay

In places never far from town

(Indeed, goldfinches often come to our bird table here in Liverpool.)

Through its association with thistles, the goldfinch came to be seen as a good-luck charm, ‘warding off contagion and bestowing symbolic health both upon those who viewed it and upon the person who owned it’. Thus the goldfinch came to be a symbol of endurance and, in the case of paintings of the Madonna and child this symbolism was transferred to the Christ child, an allegory of the salvation Christ would bring through his sacrifice.

Carlo Crivelli, ‘Madonna and Child’, 1480

In the Venetian artist Carlo Crivelli’s Madonna and Child, apples and a phallic and misshapen cucumber symbolise sin and a fly evil; they are opposed to the goldfinch, symbol of redemption from the belief that when Christ was crucified, a goldfinch perched on his head and began to extract thorns from the crown that soldiers had placed there.

Detail from Raphael’s ‘Madonna del Cardellino’ (‘Madonna of the Goldfinch’).

In Birds and People, Mark Cocker makes a broader point: that the story of the goldfinch in late medieval art is an indication of how our views of nature have changed. Until relatively recently most people ‘genuinely thought birds existed to fulfil very specific human ends’. He quotes one 18th century author as asserting: ‘Singing birds were undoubtedly designed by the Great Author of Nature on purpose to entertain and delight mankind’.

Which, in a way, brings us back to Fabritius’s goldfinch. Cocker describes the goldfinch as ‘thrice-cursed as a cagebird’: once by its beauty, then by its pleasant song, described by one writer as ‘more expressive of the joy of living than of challenge to rivals’, and finally by its dextrous coordination of bill and feet. In order to feed off thistle heads, the goldfinch has developed the ability to hold down an object with its toes while pulling parts towards them.

Carel Fabritius’s ‘Goldfinch’,1654: ‘thrice-cursed’.

It was precisely these three ‘curses’ that resulted in the predicament of the bird in Fabritius’s painting. Finches like the chaffinch and goldfinch were highly valued as cagebirds for their melodious song, but goldfinches brought something more: they became popular house pets in Holland, kept in captivity attached to a chain and trained to perform the trick of drawing water from a glass placed below the perch by lowering a thimble-sized cup into the glass.

It’s not beyond the bounds of probability that Fabritius, making this painting six years after the United Provinces had gained their independence from Spain, also expected his viewers to read his work as an allegory of freedom chained. In this sense, the painting shares an emotional character with Thomas Hardy’s poem ‘The Caged Goldfinch’:

Within a churchyard, on a recent grave,

I saw a little cage

That jailed a goldfinch. All was silence save

Its hops from stage to stage.

There was inquiry in its wistful eye,

And once it tried to sing;

Of him or her who placed it there, and why,

No one knew anything.

A few decades after Hardy, Osip Mandelstam, in ‘The Cage’ written after Stalin had ordered his arrest and internal exile in Voronezh from 1935 to 1937, summoned the goldfinch to symbolize his yearning for freedom and self-expression and rage at being caged within ‘a hundred bars of lies’:

When the goldfinch like rising dough

suddenly moves, as a heart throbs,

anger peppers its clever cloak

and its nightcap blackens with rage.

The cage is a hundred bars of lies

the perch and little plank are slanderous.

Everything in the world is inside out,

and there is the Salamanca forest

for disobedient, clever birds.

There’s another goldfinch poem by Thomas Hardy – ‘The Blinded Bird’ – that communicates the same sense of rage at freedom denied, ‘enjailed in pitiless wire’:

So zestfully canst thou sing?

And all this indignity,

With God’s consent, on thee!

Blinded ere yet a-wing

By the red-hot needle thou,

I stand and wonder how

So zestfully thou canst sing!

Resenting not such wrong,

Thy grievous pain forgot,

Eternal dark thy lot,

Groping thy whole life long;

After that stab of fire;

Enjailed in pitiless wire;

Resenting not such wrong!

Who hath charity? This bird.

Who suffereth long and is kind,

Is not provoked, though blind

And alive ensepulchred?

Who hopeth, endureth all things?

Who thinketh no evil, but sings?

Who is divine? This bird.

Hardy – who was an antivivisectionist and founder-member of the RSPCA – wrote the poem as a protest against the Flemish practice of Vinkensport in which finches are made to compete for the highest number of bird calls in an hour. In preparation for the contests, birds would be blinded with hot needles in order to reduce visual distractions and encourage them to sing more. In 1920, after a campaign by blind World War I veterans supported by Hardy the practice was banned. Vinkensport – considered part of traditional Flemish culture – continues today, though the birds are now kept in small wooden boxes that let air in but keep distractions out.

Writing this now brings back the memory of standing in a narrow street in Naples this spring, echoing with the roar of motorcycles and the shouts of people passing. Above the din, I heard a bird sing. Opposite, a tenement rose up, balconies draped with the morning’s washing, and on a fourth floor balcony, my eyes found the bird that sang. Some kind of finch, it was trapped in a cage no more than twice its size. I wrote about that experience back in April, and of the poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar that gave Maya Angelou the title of the first volume of her autobiography:

I know why the caged bird sings, ah me,

When his wing is bruised and his bosom sore,—

When he beats his bars and he would be free;

It is not a carol of joy or glee,

But a prayer that he sends from his heart’s deep core,

But a plea, that upward to Heaven he flings —

I know why the caged bird sings!

Leonardo da Vinci, ‘Madonna Litta’, detail

Maybe Hardy had read Leonardo da Vinci’s words on the goldfinch:

The gold-finch is a bird of which it is related that, when it is carried into the presence of a sick person, if the sick man is going to die, the bird turns away its head and never looks at him; but if the sick man is to be saved the bird never loses sight of him but is the cause of curing him of all his sickness.

Like unto this is the love of virtue. It never looks at any vile or base thing, but rather clings always to pure and virtuous things and takes up its abode in a noble heart; as the birds do in green woods on flowery branches. And this Love shows itself more in adversity than in prosperity; as light does, which shines most where the place is darkest.

Ted Hughes celebrated the twitching, thrilling vitality of goldfinches in their free element in ‘The Laburnum Top’:

The Laburnum Top is silent, quite still

in the afternoon yellow September sunlight,

A few leaves yellowing, all its seeds fallen

Till the goldfinch comes, with a twitching chirrup

A suddeness, a startlement,at a branch end

Then sleek as a lizard, and alert and abrupt,

She enters the thickness,and a machine starts up

Of chitterings, and of tremor of wings, and trillings –

The whole tree trembles and thrills

It is the engine of her family.

She stokes it full, then flirts out to a branch-end

Showing her barred face identity mask

Then with eerie delicate whistle-chirrup whisperings

She launches away, towards the infinite

And the laburnum subsides to empty

Simon Armitage, in The Poetry of Birds, wonders why poets have written so many poems about birds. ‘Perhaps at some subconscious, secular level,’ he writes, ‘birds are also our souls’. He continues:

Or more likely, they are our poems. What we find in them we would hope for our work – that sense of soaring otherness. Maybe that’s how poets think of birds: as poems.

Reviewing Donna Tartt’s novel in today’s Guardian, Kamila Shamsie writes that at the conclusion of the book she leads her readers to a place of meaning: in her words, ‘a rainbow edge … where all art exists, and all magic. And … all love.’

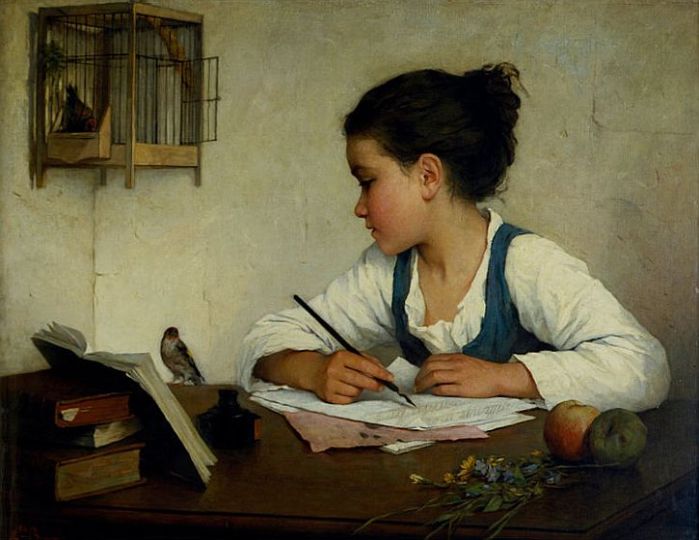

Henriette Browne, ‘A Girl Writing The Pet Goldfinch’, 1870: freedom to fly

See also

Charles Tunnicliffe at Oriel Ynys Mon: ‘the love of nature absorbed him’

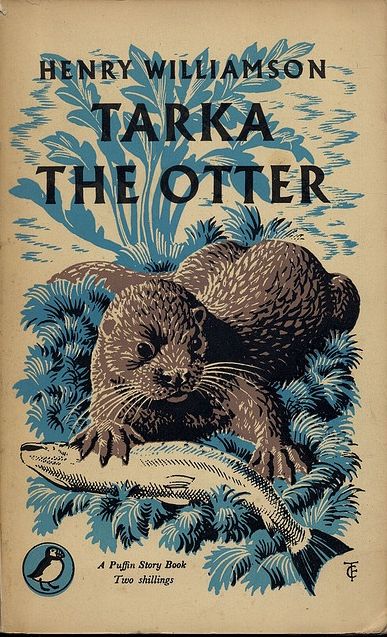

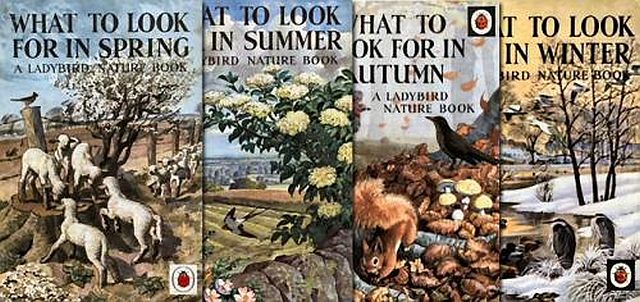

In my last post I wrote of our visit to Oriel Ynys Mon on Anglesey to see the exhibition of paintings of Venice by Kyffin Williams. It was the second time I’d been to the gallery and on both occasions I was delighted to see exhibits from the collection of work by Charles Tunnicliffe held by the gallery. If you grew up in the fifties like me you probably read Ladybird nature books and collected Brooke Bond tea cards – all illustrated by Tunnicliffe. You might even have read the Puffin edition of Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter, with its cover and beautiful illustrations also by Tunnicliffe.

Another reason for my interest in Tunnicliffe is that he grew up not far from where I lived. He was born in 1901 in Langley, just outside Macclesfield, and spent his early years on a farm at nearby Sutton Lane Ends where he helped out with daily tasks and began to take a keen interest in observing animals and birds closely. There’s an early drawing, The Kestrel, which I’m pretty certain depicts the view from there, with the Cheshire plain and the smoking chimneys of Macclesfield’s textile and silk mills smoking in the distance.

At the village school he learned to draw and became interested in art, later winning a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in London where he rubbed shoulders with Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and Edward Burra. After graduating Tunnicliffe began to make a living from selling etchings and engravings of rural scenes, but with the onset of the depression in 1930s the market for prints declined, so he began to teach illustration and graphic design. His big breakthrough came in 1932 after his wife had encouraged him to submit illustrations for a new edition of Henry Williamson’s best-selling novel Tarka the Otter. It was this series of wood engravings that bought Tunnicliffe widespread recognition.

In 1947 Tunnicliffe’s long association with Anglesey began when he moved from Manchester to ‘Shorelands’ a cottage at Malltraeth, on the estuary of the Afon Cefni near Newborough, where he lived until his death in 1979. On Anglesey, Tunnicliffe set about consolidating his knowledge of the island’s many bird haunts. In 1952, one of his best-loved books, Shorelands Summer Diary, was published – one of the artist’s masterpieces, it’s an evocative record of one glorious season on Anglesey. In 1954, Tunnicliffe was elected a fellow of the Royal Academy in recognition, not just of his excellence as an illustrator and bird portraitist, but also for the breadth of his achievement in a variety of media – watercolour, pen and ink, woodblock engraving, etching and scraperboard – and across a variety of subject matter.

His name became a familiar one to kids like me in the 1950s, reading the Ladybird Books that he illustrated (I remember I used to own the ‘seasons’ series) and collecting the Brooke Bond tea cards that featured his meticulous paintings of birds and wild flowers. One of the first albums I collected was the set of his bird portraits from 1957.

By the sixties, my brother – ten years younger than me – was collecting Brooke Bond cards. This is a spread from the Tunnicliffe-illustrated album Wild Birds in Britain album of 1965, which contains this prescient introduction by Tunnicliffe:

There is always something new to be discovered about birds. Also we must not forget their beauty – a difficult quality to define, but one which is made up of form and colour, balance and movement ~ quality to which all sensitive and alert people respond, and which birds have in abundance. Surely, then, these value able creatures are worthy of our care and protection. But alas! modern man’s activities are, on the whole, against their survival. Towns increase in size, land is drained, harmful chemicals are used in the cultivation of the soil, more and more people shoot birds, and so the destruction goes on. Will many of our birds be but a memory in a few years to come ? Some are already just that.

In Tunnicliffe’s bird paintings, artistic interpretation was rooted in meticulous observation and precise scientific method. This is powerfully illustrated in the current display of the artist’s work at Oriel Ynys Mon, which features a number of the measured drawings through which Tunnicliffe recorded – from various angles and to within a millimetre of accuracy – the details of specimens that had been brought to him.

These post-mortem studies (always the result of chance – Tunnicliffe never countenanced the killing of birds) he called his ‘feather maps’; they were used as the basis for his finished works.

The current exhibits include several astonishingly detailed measured drawings of birds – and one of a fox which I found particularly breathtaking. These are large works – near to life-size, and every detail of the animal’s anatomy and colouring had been carefully observed, with the fine detail of each hair of the fox’s coat almost visible.

Peter Scott, the ornithologist, broadcaster and fellow artist, believed that ‘the verdict of posterity in time to come is likely to rate Charles Tunnicliffe the greatest wildlife artist of the twentieth century’. Looking at the measured drawings, you think he might be right.

Another source leading to the finished works were the high-speed drawings that Tunnicliffe made in the field, especially around Cob Lake, the Cefni Estuary, South Stack Cliffs, Llyn Coron, Aberfraw, and Cemlyn. These were then worked up in a superb set of sketchbooks full of accurate and colourful ‘memory drawings’.

These sketchbooks are works of art in themselves, and examples of these are on display at Oriel Ynys Mon, too. The open pages reveal the drawings and watercolours that the artist made to quickly record the details of the colouring and movement of a particular bird or animal. Alongside, he would add copious hand-written notes.

Tunnicliffe kept his sketchbooks and measured drawings at home in Anglesey until the end of his life. He could not work without them and always had them by his side for reference. At his death, much of his personal collection of work was bequeathed to Anglesey council on the condition that it was housed together and made available for public viewing. This is the body of work which can now be seen at Oriel Ynys Môn.

There’s one painting of Tunnicliffe’s, Coming in to Land, which must have been painted from sketches made at the mouth of Afon Cefni, looking toward the lighthouse of Ynys Llanddwyn and the Snowdonia mountains beyond. It depicts one of my favourite sights, a skein of geese in flight. You can hear the honking. There’s a beautifully-composed, balletic quality to Curlews Alighting, below.

Sometimes there is a tendency to dismiss the work of an artist like Tunnicliffe as mere illustration, but, as his friend Kyffin Williams said in a tribute to Tunnicliffe at the time of his first major Anglesey exhibition:

If this was so, it didn’t worry the countryman from Cheshire for his work was done for love: love of birds and of animals, of the wild flowers on the rocks above the sea, of the wind, of the sun and of the changing seasons.

The love of nature absorbed him … Every day he worked; in the fields, on the shore, in the Anglesey marshes and in his studio overlooking the sea. When the world of art was arguing to decide what was art and what was not, Charles Tunnicliffe just lived and worked. […]

The best of his measured drawings are great works of art, as are some of his wood engravings and etchings. All these were done from deep knowledge, so the integrity is immense, as in his wonderful etching of the sitting hare.

Indeed; it might be Durer.

Or take Dry Clothes and Rain, a work from around 1926 that hangs in Macclesfield’s West Bank Museum, where a room has been dedicated to his work that I must visit one day soon.

Video

Welsh language art programme Pethe looks at a 2011 exhibition at Oriel Ynys Mon of works by Kyffin Williams and Charles Tunnicliffe including archive footage of the painters at work (subtitles).

Slideshow of Tunnicliffe’s bird paintings (you may prefer to mute the soundtrack)

See also

- The Tunnicliffe collection at Oriel Ynys Mon: Tunnicliffe Society web page with many excellent images

- Charles Tunnicliffe Society website: this index has links to pages on all aspects of Tunnicliffe’s work, including his Brooke Bond tea albums

The caged bird sings: of things unknown but longed for still

Four days in Naples, and of all the images imprinted on my memory from that city of teeming alleyways and cacophonous streets, one lingers ineradicable. I was waiting outside a shop in a narrow street echoing with the roar of motorcycles and the shouts of people passing. Then, above the din, I heard a bird sing. Opposite, a tenement rose up, balconies draped with the morning’s washing, and on a fourth floor balcony, my eyes found the bird that sang. Some kind of finch, it was trapped in a cage no more than twice its size. Imprisoned, the bird was repeating the same movements over and over, the way I’ve seen a caged zoo animal pace incessantly one way and back again. The bird fluttered to a top corner of the cage and back down, over and over without pause. The song I had heard was a fearful, endless shriek.

I wanted to climb the stairs and free the bird, but of course I didn’t. But the image of that desperate flapping has not left my mind. I’ve since discovered that what I saw was just one example of a plight that ensnares countless birds in Naples. As this report indicates, birds are caught in large numbers, particularly on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius, to be openly sold on the streets of Naples despite Italian laws that outlaw finch trapping:

Goldfinches, Greenfinches and Siskins are traditionally considered to bring their owners luck in the sprawling conurbation of Naples. Everywhere in the narrow streets and alleyways of the old town, stopped up with vehicle traffic, the song of these birds can be heard from countless balconies where they are confined in small cages. For many long term residents of Naples a finch in a cage is a typical household item.

The birds are still in clap and mist nets, as well as special cage traps, above all on The birds are sold in normal pet shops, which also sell the necessary trapping accoutrements. The birds and equipment are often not just available ‘under the counter’ but are openly on sale.

The report is illustrated by the photo (above) of goldfinches and siskins seized before they were sold on the back streets of Naples.

Of course, the phrase that has been on my mind these last few days has been ‘I know why the caged bird sings’, the title of the first volume of Maya Angelou’s memorable autobiography. In naming her book, Angelou was honouring Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906), an African-American poet whose works she had admired for years, and specifically referencing the third stanza of his poem ‘Sympathy’:

I know what the caged bird feels, alas!

When the sun is bright on the upland slopes;

When the wind stirs soft through the springing grass,

And the river flows like a stream of glass;

When the first bird sings and the first bud opes,

And the faint perfume from its chalice steals —

I know what the caged bird feels!

I know why the caged bird beats his wing

Till its blood is red on the cruel bars;

For he must fly back to his perch and cling

When he fain would be on the bough a-swing;

And a pain still throbs in the old, old scars

And they pulse again with a keener sting —

I know why he beats his wing!

I know why the caged bird sings, ah me,

When his wing is bruised and his bosom sore,—

When he beats his bars and he would be free;

It is not a carol of joy or glee,

But a prayer that he sends from his heart’s deep core,

But a plea, that upward to Heaven he flings —

I know why the caged bird sings!

Maya Angelou wrote her own poem that shares the same title as her book:

The free bird leaps

on the back of the wind

and floats downstream

till the current ends

and dips his wings

in the orange sun rays

and dares to claim the sky.

But a bird that stalks

down his narrow cage

can seldom see through

his bars of rage

his wings are clipped and

his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with fearful trill

of the things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill for the caged bird

sings of freedom

The free bird thinks of another breeze

and the trade winds soft through the sighing trees

and the fat worms waiting on a dawn-bright lawn

and he names the sky his own.

But a caged bird stands on the grave of dreams

his shadow shouts on a nightmare scream

his wings are clipped and his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

There’s a poem by the American Mark Doty, ‘Migratory’, that speaks of longing, of our homesickness for the wild. As John Burnside observed in a recent New Statesman article, it is a poem that

both delineates and accepts the limitations of being human, rather than animal …. As the birds fly over and away from him, forcing the speaker to admit ‘I wasn’t with them . . . of course I wasn’t’, we nevertheless see that, for the moment at least, he is touched with wonder and a lingering faith in a natural order that we all too frequently ignore. He has seen – and to see another animal in its true light, however briefly, is to recover a little of the connection that makes us compassionate, which is to say: whole. The leap skyward that Doty imagines reminds us that, unless we are able to experience the world, not just alongside but with other living things, we are incomplete. Compassion isn’t just what makes us human; it is what makes us real.

Near evening, in Fairhaven, Massachusetts,

seventeen wild geese arrowed the ashen blue

over the Wal-mart and the Blockbuster Video,

and I was up there, somewhere between the asphalt

and their clear dominion – not in the parking lot,

the tallowy circles just appearing,

the shopping carts shining, from above,

like little scraps of foil. Their eyes

held me there, the unfailing gaze

of those who know how to fly in formation,

wing-tip to wing-tip, safe, fearless.

And the convex glamour of their eyes carried

the parking lot, the wet field

troubled with muffler shops

and stoplights, the arc of highway

and its exits, one shattered farmhouse

with its failing barn…The wind

a few hundred feet above the grass

erases the mechanical noises, everything;

nothing but their breathing

and the perfect rowing of the pinions,

and then, out of that long, percussive pour

toward what they are most certain of,

comes their – question, is it?

Assertion, prayer, aria – as delivered

by something too compelled in its passage

to sing? A hoarse and unwieldy music

which plays nonetheless down the length

of me until I am involved in their flight,

the unyielding necessity of it, as they literally

rise above, ineluctable, heedless,

needing nothing…Only animals

make me believe in God now

– so little between spirit and skin,

any gesture so entirely themselves.

But I wasn’t with them,

as they headed toward Acushnet

and New Bedford, of course I wasn’t,

though I was not exactly in the parking lot

either, with the cars nudged in and out

of their slots, each taking the place another

had abandoned, so that no space, no desire

would remain unfilled. I wasn’t there.

I was so filled with longing

– is that what that sound is for? –

I seemed to be nowhere at all.

Recently I’ve been reading Michael Symmons Roberts’ new collection Drysalter; among the fine poems is this hymn to birds, the risks they run and the meaning they hold for us, epitomised in the sound of the dawn chorus:

It begins in song, in fact in songs, such chaos

it’s as if each dead bird is reborn to join

the same dawn chorus: all those shot, mauled,

widow-blind, the roadkill, those whose

gist gave out in mid-migration, those whose

picking at the dry soil drew a blank, now caught

in one tremendous rinse and swoon of multiples

then down the song stoops circling and the tone

slides from tin to wood to stone it tips into

the vortex of its making, a sheer weight

of song too great to hold still and the birds

themselves are sucked in with it, corkscrew

curl of down, crop, tail and crest until it all

collapses into one dun thrush, a dusk yard,

cherry bough, a single note swells in its gullet.

(‘Abyss of Birds’)

Now I know that Spring will come again. Perhaps to-morrow?

Yesterday the first day of spring, today blizzards in a north-east wind. Winter hasn’t let go this year: we’ve been stuck with anticyclonic conditions for three weeks, and this has sucked in cold air from Scandinavia. For a while the weather was crisp, then it turned cold, damp and murky. Today, an Atlantic weather front pushing in has met that cold air from the north-east and, here on Merseyside, we’ve had heavy, wet snow swept along in blizzard conditions. Not what you expect in late March, least of all in Liverpool.

Yesterday the Guardian, in an article on the unseasonal weather, noted that

One hundred years ago, on the official first day of spring, the Anglo-Welsh poet and naturalist Edward Thomas set off from Clapham Common in London to cycle and walk to the Quantock Hills in Somerset. The record of his journey, called In Pursuit of Spring, became a nature-writing classic, telling of exuberant chiffchaffs and house martins, daffodils and cowslips in full flower and ‘honeysuckle in such profusion as I had never before seen’. Had Thomas taken the same route today, he might not have seen very much wildlife – and could well have frozen. Mist and fog, rain, a bitter north wind, and temperatures just above freezing are forecast for , the first “official” day of spring.

Certainly not much sign of honeysuckle around these parts, and the daffodils and crocus are only just starting to show. This time last year it was very different: a heatwave and barbecues in the park. But, as Edward Thomas was well aware, it’s not unusual for winter to hold on through March; he wrote a poem about it:

Now I know that Spring will come again,

Perhaps to-morrow: however late I’ve patience

After this night following on such a day.

While still my temples ached from the cold burning

Of hail and wind, and still the primroses

Torn by the hail were covered up in it,

The sun filled earth and heaven with a great light

And a tenderness, almost warmth, where the hail dripped,

As if the mighty sun wept tears of joy.

But ’twas too late for warmth. The sunset piled

Mountains on mountains of snow and ice in the west:

Somewhere among their folds the wind was lost,

And yet ’twas cold, and though I knew that Spring

Would come again, I knew it had not come,

That it was lost too in those mountains chill.

What did the thrushes know? Rain, snow, sleet, hail,

Had kept them quiet as the primroses.

They had but an hour to sing. On boughs they sang,

On gates, on ground; they sang while they changed perches

And while they fought, if they remembered to fight:

So earnest were they to pack into that hour

Their unwilling hoard of song before the moon

Grew brighter than the clouds. Then ’twas no time

For singing merely. So they could keep off silence

And night, they cared not what they sang or screamed;

Whether ’twas hoarse or sweet or fierce or soft;

And to me all was sweet: they could do no wrong.

Something they knew–I also, while they sang

And after. Not till night had half its stars

And never a cloud, was I aware of silence

Stained with all that hour’s songs, a silence

Saying that Spring returns, perhaps to-morrow.

I’ve remarked here before that I revere the Country Diary written by Paul Evans in the Guardian. Go here for the full text, but this is part of the entry he wrote yesterday:

Today is the vernal equinox: equal day, equal night, a moment of balance poised between the cold grey of winter and the green fire of spring.

Watching the budget on the news, I wait for George Osborne’s primavera moment, when zephyrs blow flowers through the halls of Westminster and birdsong drowns out the hectoring. Hope over experience, eh? He’s only going to frack it up so I switch off and walk outside where spring should be champing at the bit.

This time last year was sunny and warm, I saw butterflies and bees and at dusk bats flying under a strangely fat moon. What have they done with the spring? We had a day of it a fortnight ago and since then it’s been snow, hail, rain, fog. The ground is unyielding, greasy, sullen. Wallflowers and polyanthus are stunned by frost. A few sulky daffodils peer earthwards. Snowdrops are hanging on like a pillow burst of feathers from a peregrine kill, beautiful and pointless. […]

I stand under a dishwater sky, bone cold, cold as charity. Geese honk, hens cluck, small birds whistle without passion. The buds hold, tight-fisted, their little hopes. Between yesterday’s hail and tomorrow’s rain, the gutters run. I rummage through rattley hedges for that still point, the moment of balance where light and dark are equal, life and death cancel each other out. It’s a new beginning of sorts. Even though spring still feels as though it’s stuck up to its axles in mud, there is an urgency in the voices of birds. We agree.

It’s the birds I notice too on my morning dog walks through the park. The other day I was astonished when a pair of scuffling male blackbirds flew out of a shrubbery and continued their mid-air wing-flapping sorting out of the pecking order at shoulder height just an arm’s length in front of me; they only gave up and flew off after I had reached out an arm. There’s a song thrush that always singing loud and sweet in the same tree by the Palm House every morning, and a heron that stands, shoulders hunched like an old judge, staring at the stream. The nuthatch whose song I was pleased to identify last year is back in the same tree, making the same electronic, staccato call.

After this morning’s walk in the park with the dog, at breakfast we watched for some time as a fox poked around the back garden, sniffing at the fat balls hanging for the birds, and scrounging some fallen bird seed. The cold making for hunger, I expect. Yesterday there was a different fox on the back wall; that one had a tail like a broom: smooth for most of its length, but ending with a furry flourish.

A Single Swallow

The swallows have long gone from the park fields; they no longer swoop and dive around me as I walk the dog there. By now they are probably some where over the tropical forests of central Africa; by Christmas many will have reached South Africa. The extraordinary journey that swallows make on their annual migration has fascinated me since, as a child growing up in a Cheshire village, I would see swallows gather in late August or September on telephone wires and I would know that summer was nearly over and I would marvel at the great journey they were about to make.

The swallow of summer, cartwheeling through crimson,

Touches the honey-slow river and turning

Returns to the hand stretched from under the eaves –

A boomerang of rejoicing shadow.

– Ted Hughes, from ‘Work and Play’

I suppose it was this unending fascination that led me, in a bookshop in the summer, to pick up and buy A Single Swallow: Following the migration from South Africa to South Wales by Horatio Clare. I saved it for the end of summer, and finished reading it a couple of weeks ago.

When I finally settled down to read the book it was, at first, a disappointment. This is not a book about swallows: it is, rather, a travel book in which swallows make only an occasional appearance. But, as soon as I had adjusted to this mistake on my part, I found myself absorbed in Clare’s story of his journey north through Africa, swept along by Clare’s engagingly generous account of the characters he meets along the way. For the strength of this book lies in Clare’s vivid portrayal of encounters with humans, rather than the birds he is ostensibly following.