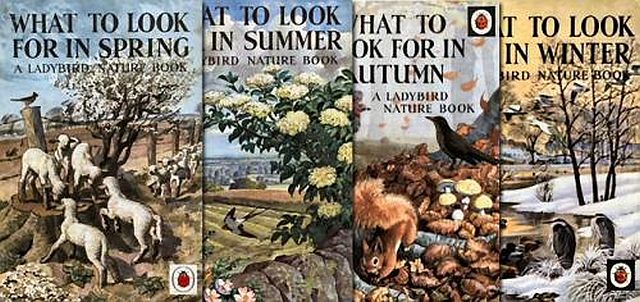

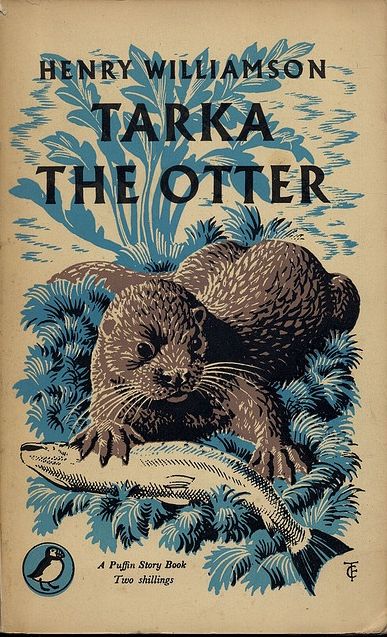

In my last post I wrote of our visit to Oriel Ynys Mon on Anglesey to see the exhibition of paintings of Venice by Kyffin Williams. It was the second time I’d been to the gallery and on both occasions I was delighted to see exhibits from the collection of work by Charles Tunnicliffe held by the gallery. If you grew up in the fifties like me you probably read Ladybird nature books and collected Brooke Bond tea cards – all illustrated by Tunnicliffe. You might even have read the Puffin edition of Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter, with its cover and beautiful illustrations also by Tunnicliffe.

Another reason for my interest in Tunnicliffe is that he grew up not far from where I lived. He was born in 1901 in Langley, just outside Macclesfield, and spent his early years on a farm at nearby Sutton Lane Ends where he helped out with daily tasks and began to take a keen interest in observing animals and birds closely. There’s an early drawing, The Kestrel, which I’m pretty certain depicts the view from there, with the Cheshire plain and the smoking chimneys of Macclesfield’s textile and silk mills smoking in the distance.

At the village school he learned to draw and became interested in art, later winning a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in London where he rubbed shoulders with Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and Edward Burra. After graduating Tunnicliffe began to make a living from selling etchings and engravings of rural scenes, but with the onset of the depression in 1930s the market for prints declined, so he began to teach illustration and graphic design. His big breakthrough came in 1932 after his wife had encouraged him to submit illustrations for a new edition of Henry Williamson’s best-selling novel Tarka the Otter. It was this series of wood engravings that bought Tunnicliffe widespread recognition.

In 1947 Tunnicliffe’s long association with Anglesey began when he moved from Manchester to ‘Shorelands’ a cottage at Malltraeth, on the estuary of the Afon Cefni near Newborough, where he lived until his death in 1979. On Anglesey, Tunnicliffe set about consolidating his knowledge of the island’s many bird haunts. In 1952, one of his best-loved books, Shorelands Summer Diary, was published – one of the artist’s masterpieces, it’s an evocative record of one glorious season on Anglesey. In 1954, Tunnicliffe was elected a fellow of the Royal Academy in recognition, not just of his excellence as an illustrator and bird portraitist, but also for the breadth of his achievement in a variety of media – watercolour, pen and ink, woodblock engraving, etching and scraperboard – and across a variety of subject matter.

His name became a familiar one to kids like me in the 1950s, reading the Ladybird Books that he illustrated (I remember I used to own the ‘seasons’ series) and collecting the Brooke Bond tea cards that featured his meticulous paintings of birds and wild flowers. One of the first albums I collected was the set of his bird portraits from 1957.

By the sixties, my brother – ten years younger than me – was collecting Brooke Bond cards. This is a spread from the Tunnicliffe-illustrated album Wild Birds in Britain album of 1965, which contains this prescient introduction by Tunnicliffe:

There is always something new to be discovered about birds. Also we must not forget their beauty – a difficult quality to define, but one which is made up of form and colour, balance and movement ~ quality to which all sensitive and alert people respond, and which birds have in abundance. Surely, then, these value able creatures are worthy of our care and protection. But alas! modern man’s activities are, on the whole, against their survival. Towns increase in size, land is drained, harmful chemicals are used in the cultivation of the soil, more and more people shoot birds, and so the destruction goes on. Will many of our birds be but a memory in a few years to come ? Some are already just that.

In Tunnicliffe’s bird paintings, artistic interpretation was rooted in meticulous observation and precise scientific method. This is powerfully illustrated in the current display of the artist’s work at Oriel Ynys Mon, which features a number of the measured drawings through which Tunnicliffe recorded – from various angles and to within a millimetre of accuracy – the details of specimens that had been brought to him.

These post-mortem studies (always the result of chance – Tunnicliffe never countenanced the killing of birds) he called his ‘feather maps’; they were used as the basis for his finished works.

The current exhibits include several astonishingly detailed measured drawings of birds – and one of a fox which I found particularly breathtaking. These are large works – near to life-size, and every detail of the animal’s anatomy and colouring had been carefully observed, with the fine detail of each hair of the fox’s coat almost visible.

Peter Scott, the ornithologist, broadcaster and fellow artist, believed that ‘the verdict of posterity in time to come is likely to rate Charles Tunnicliffe the greatest wildlife artist of the twentieth century’. Looking at the measured drawings, you think he might be right.

Another source leading to the finished works were the high-speed drawings that Tunnicliffe made in the field, especially around Cob Lake, the Cefni Estuary, South Stack Cliffs, Llyn Coron, Aberfraw, and Cemlyn. These were then worked up in a superb set of sketchbooks full of accurate and colourful ‘memory drawings’.

These sketchbooks are works of art in themselves, and examples of these are on display at Oriel Ynys Mon, too. The open pages reveal the drawings and watercolours that the artist made to quickly record the details of the colouring and movement of a particular bird or animal. Alongside, he would add copious hand-written notes.

Tunnicliffe kept his sketchbooks and measured drawings at home in Anglesey until the end of his life. He could not work without them and always had them by his side for reference. At his death, much of his personal collection of work was bequeathed to Anglesey council on the condition that it was housed together and made available for public viewing. This is the body of work which can now be seen at Oriel Ynys Môn.

There’s one painting of Tunnicliffe’s, Coming in to Land, which must have been painted from sketches made at the mouth of Afon Cefni, looking toward the lighthouse of Ynys Llanddwyn and the Snowdonia mountains beyond. It depicts one of my favourite sights, a skein of geese in flight. You can hear the honking. There’s a beautifully-composed, balletic quality to Curlews Alighting, below.

Sometimes there is a tendency to dismiss the work of an artist like Tunnicliffe as mere illustration, but, as his friend Kyffin Williams said in a tribute to Tunnicliffe at the time of his first major Anglesey exhibition:

If this was so, it didn’t worry the countryman from Cheshire for his work was done for love: love of birds and of animals, of the wild flowers on the rocks above the sea, of the wind, of the sun and of the changing seasons.

The love of nature absorbed him … Every day he worked; in the fields, on the shore, in the Anglesey marshes and in his studio overlooking the sea. When the world of art was arguing to decide what was art and what was not, Charles Tunnicliffe just lived and worked. […]

The best of his measured drawings are great works of art, as are some of his wood engravings and etchings. All these were done from deep knowledge, so the integrity is immense, as in his wonderful etching of the sitting hare.

Indeed; it might be Durer.

Or take Dry Clothes and Rain, a work from around 1926 that hangs in Macclesfield’s West Bank Museum, where a room has been dedicated to his work that I must visit one day soon.

Video

Welsh language art programme Pethe looks at a 2011 exhibition at Oriel Ynys Mon of works by Kyffin Williams and Charles Tunnicliffe including archive footage of the painters at work (subtitles).

Slideshow of Tunnicliffe’s bird paintings (you may prefer to mute the soundtrack)

See also

- The Tunnicliffe collection at Oriel Ynys Mon: Tunnicliffe Society web page with many excellent images

- Charles Tunnicliffe Society website: this index has links to pages on all aspects of Tunnicliffe’s work, including his Brooke Bond tea albums

These are beautiful Gerry. There is a book of Charles Tunnicliffe’s bird drawings displayed inside South Stack Lighthouse which we saw early in the summer this year. Beautifully and accurately done. The gulls and their chicks living in the Lighthouse garden all looked like close relatives of his models.

Thanks, Ronnie. We’ve never gone right down to the lighthouse at South Stack. Next year we must.

Delightful piece!

Lovely reminder – I had/have those Ladybird books and the bird portrait cards but had not connected those and his other work!

We were lucky kids in the fifties.

Lovely article, I lived not far from Shorelands in a house which had several Tunnicliffe paintings.

The Coming in to Land is not quite by the mouth of the Cefni you can locate the wreck of the Athena 1852 Traeth Penrhos Malltraeth Bay http://www.streetmap.co.uk/map.srf?X=238500&Y=364500&A=Y&Z=120

Thank you. Great article. I’m about to make my first visit to Anglesey and the Tunnicliffe Museum. Brian Long, New Mexico, USA

I Met Brian Long today along with Philip Snow and Paul Rogers (Shorelands, where Tunnicliffe lived). Brian visited Oriel Ynys Mon yesterday and was shown the Tunnicliffe collection by Ian Jones. Brian knew a great deal about Charles Tunnicliffe’s work but was amazed at the Oriel’s collection and the dedication of the staff, particularly the assistance of Ian. My meeting with Brian revealed his own abilities as an artist, naturalist and researcher. Brian was also interested in Philip’s outstanding artwork and Paul’s knowledge of wildlife artists and natural history. Brian hails from New Mexico and travels light, spending time with friends and camping in a small tent. His enthralment with Tunnicliffe’s work and fascination with Anglesey has kept him exploring the island for a few more days. He has just been dropped off in the middle of Newborough’s Forest in search of Crossbills and other species Tunnicliffe would have depicted. My parting comment was “Don’t get lost”. His wry smile was understandable, as he has ventured into some of the wildest forests of America and the world. His next destination is France, where he hopes to see and record the various regions’ wildlife.

Bon Voyage, Hwyl fawr, John Smith