The morning was warm, but there was a pleasant breeze that blew white, puffy clouds across a blue sky as we set off across the Cob to Malltraeth. There was no hint of the scorching hours to come.

We had decided to walk along the Cob to the village where the wildlife artist Charles Tunnicliffe had once made a home, and then to return the same way before exploring the Cefni salt-marsh and looping back to the car park via Llanddwyn beach and the track through Newborough Forest.

The Cob and the salt-marsh

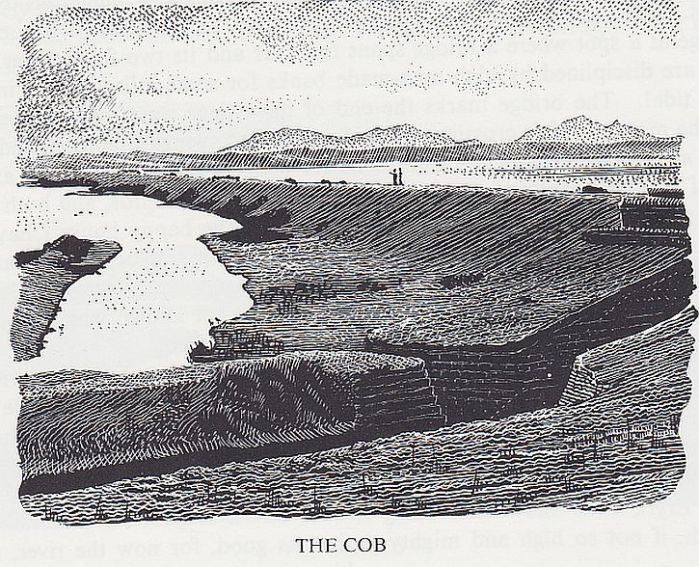

The Cob is a mile long embankment, over which the Anglesey Coastal path runs. It is part of a flood defence system, completed in 1812 under the direction of Thomas Telford, which enabled the Cefni Marsh to be drained to facilitate the construction of the A5 turnpike road to the port of Holyhead. Today, the Cob encloses the ‘Pool’, a nature reserve managed by the Countryside Council for Wales. Cefni Marsh is designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, and is the location of an RSPB reserve.

Cefni Marsh and the Pool from the Cob

It was the birds that brought Tunnicliffe here. Like me, he was born in Cheshire and spent his childhood on the family farm, not far from the village where I grew up. He studied art in Macclesfield and won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art.

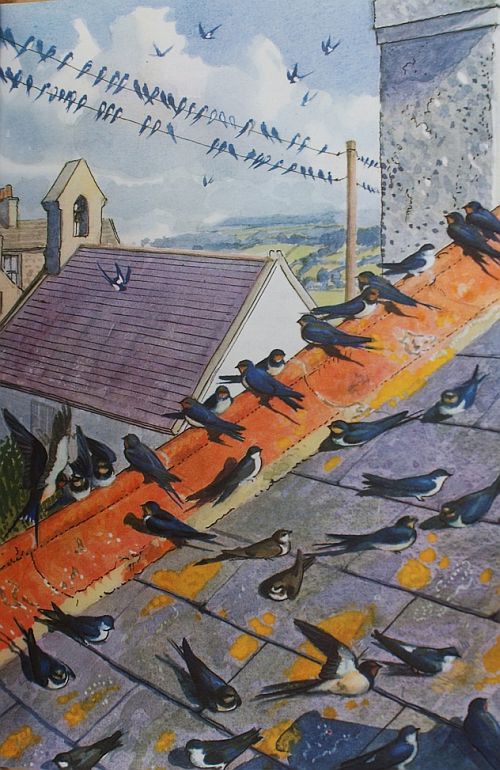

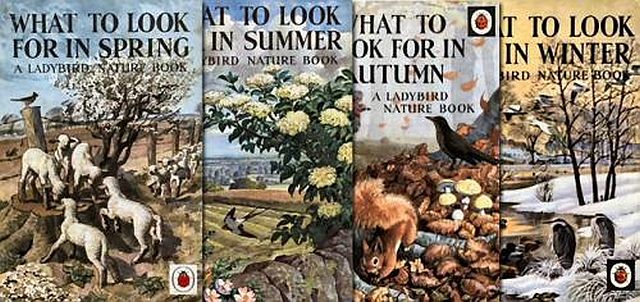

Charles Tunnicliffe, Swallows on the roof of Shorelands (illustration for ‘What to Look for in Autumn’, Ladybird Books)

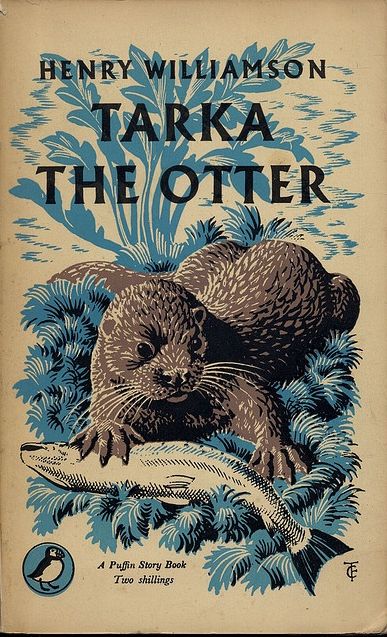

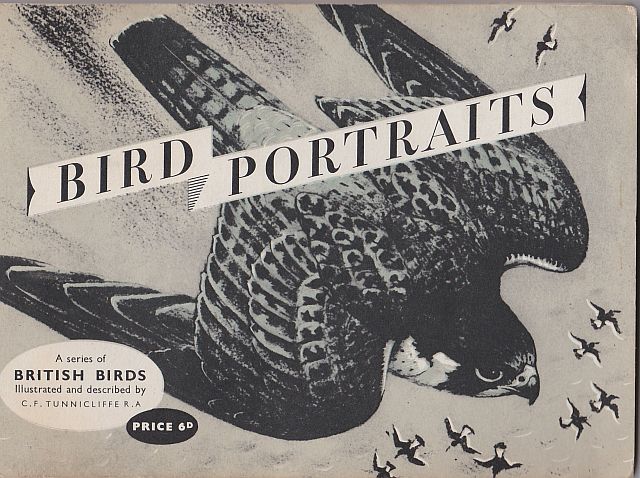

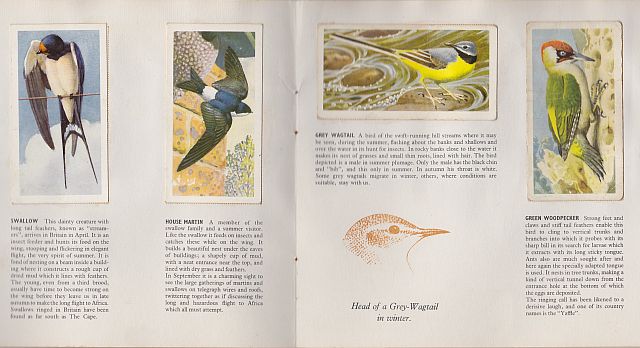

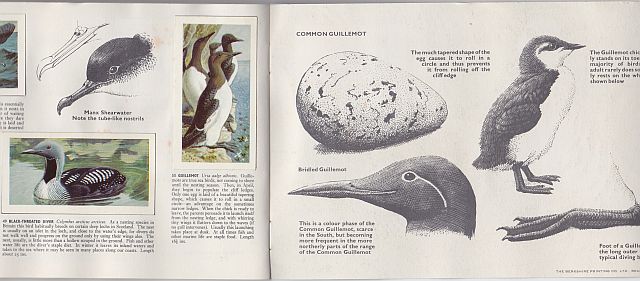

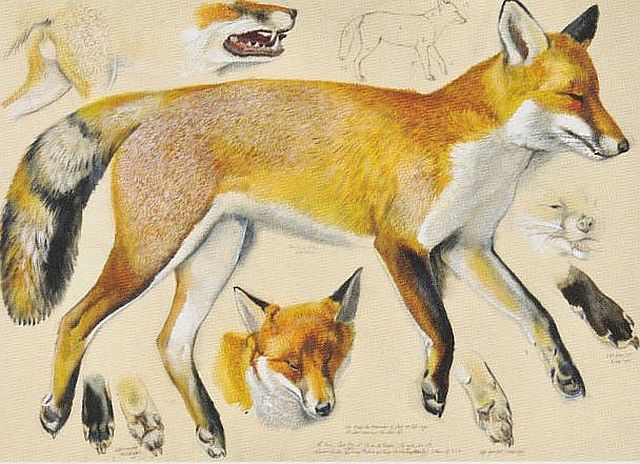

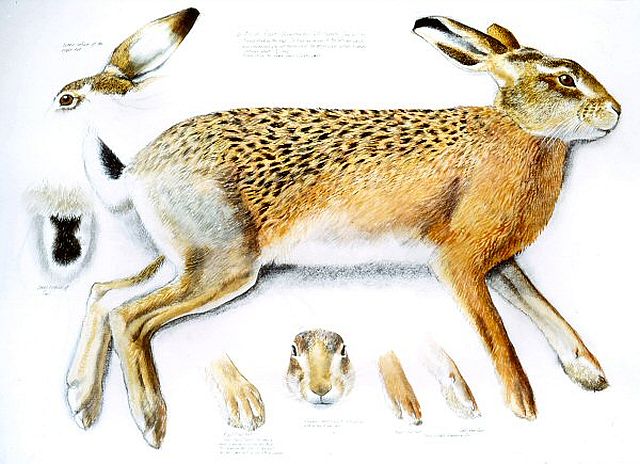

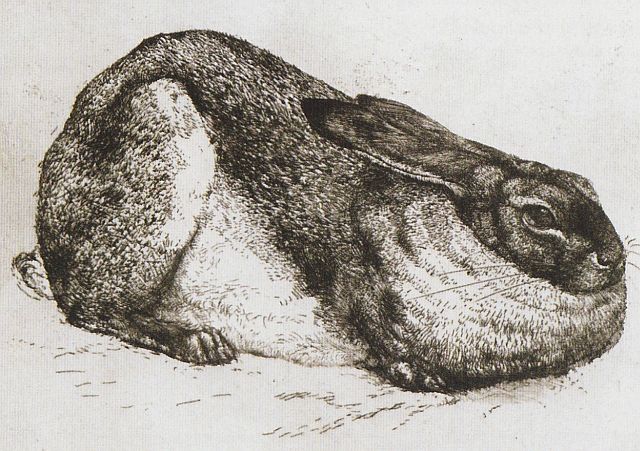

Soon he had made his name as a prolific and highly talented commercial artist and engraver whose subject was the countryside and wildlife. In 1932 he illustrated Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter, and in the 1950s and 60s he became widely known for his children’s book illustrations (including the immensely popular Ladybird ‘Seasons’ series) and his wildlife illustrations for cards given away with packets of Brooke Bond tea.

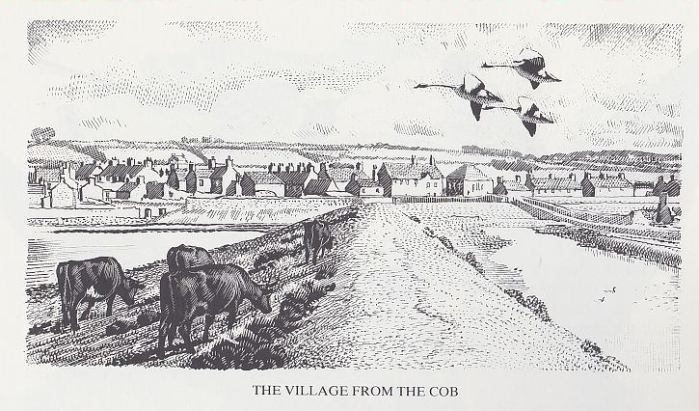

Charles Tunnicliffe, Malltraeth village from the Cob (illustration from ‘Shorelands Summer Diary’)

In 1947, Tunnicliffe and his wife Winifred came to live on Anglesey in a house in Malltraeth called ‘Shorelands’ which looked out directly over the Cefni estuary. In Shorelands Summer Diary (1952) he described their arrival:

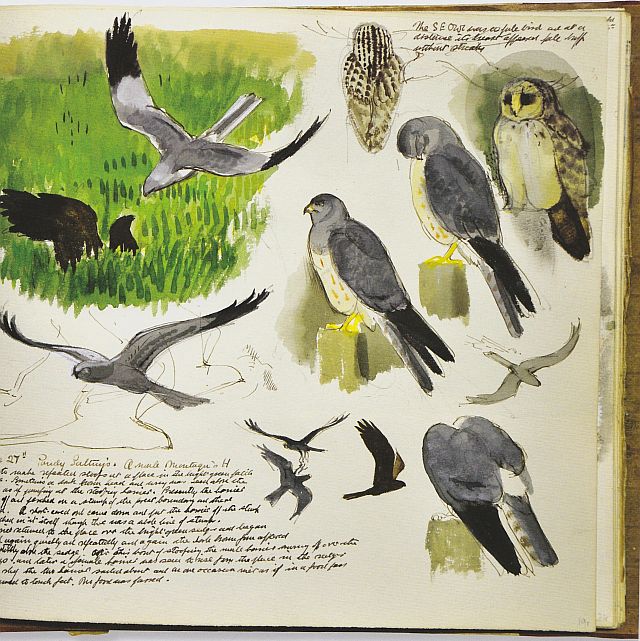

On the evening of March the 27th, my wife and I crossed over Telford’s great bridge which spans the Menai Straits, and entered the island county of Anglesey. We were no strangers to this fair country, but our journey to-day was different from all previous ones for, at the end of it, in a little grey village at the head of an estuary, there was an empty house which we hoped to call home as soon as we could get our belongings into it. Our other visits had been short holidays, spent chiefly in watching and drawing birds and landscape of which there was great variety. Several sketch-books and been filled with studies of Anglesey and its birds, and we had been specially delighted to find that he island in spring and autumn was a calling place for many migratory birds, while summer and winter had their own particular and different species. Occasionally, to add to the excitement, a rarity would appear. Whatever the season there were always birds and this fact had greatly influenced us in our choice of a new home. […]

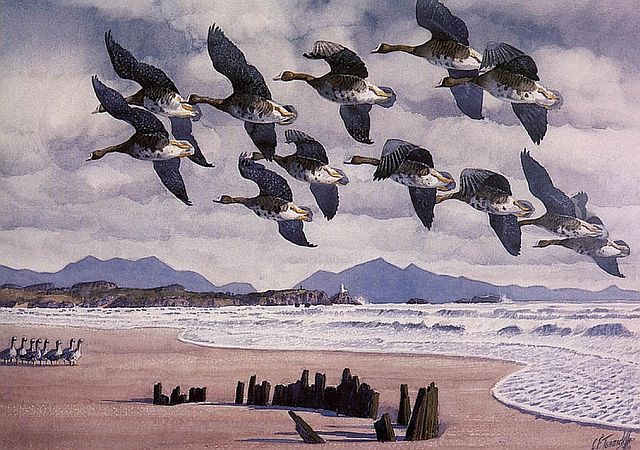

The sun shone, the furniture went into the house … and the Sheldrucks on the sands laughed and cackled all day. There followed days of arranging and re-arranging and gradually order emerged from chaos, the proceedings often suspended while we gazed from the windows. Field-glasses and telescope were always kept in readiness for a sudden grab, but it was astonishing how often they became buried under other material not yet put in its proper place. such was the case when we heard the call of wild geese one evening…

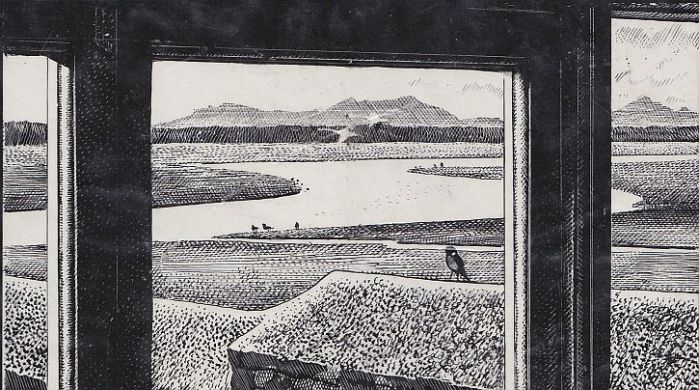

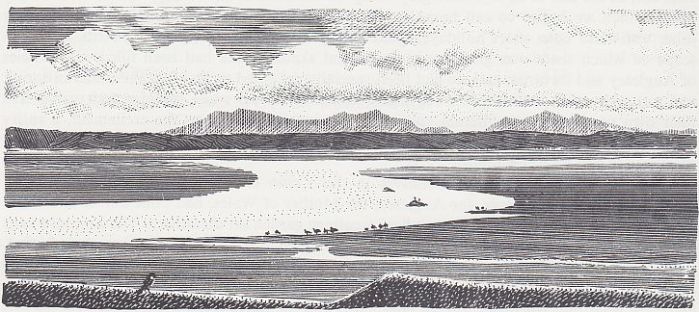

The view of the estuary from Shorelands (illustration from ‘Shorelands Summer Diary’)

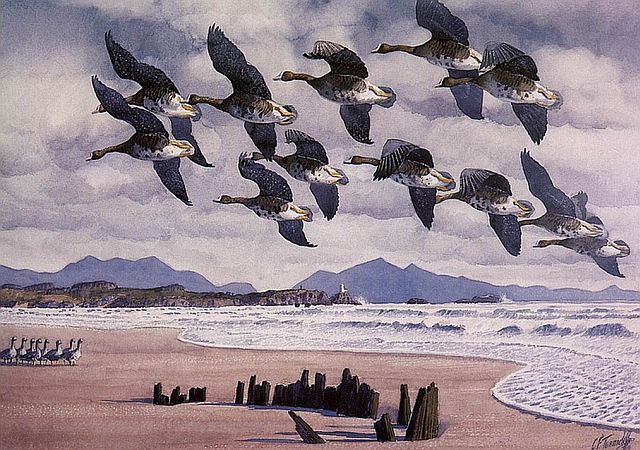

With the abundance of bird life and the views across to the distant mountains of Snowdonia, Tunnicliffe settled into a life of painting his favourite subjects. From the window of his studio at ‘Shorelands’, overlooking the estuary, he observed and painted. He watched the birds fishing along the shoreline, the oystercatchers pausing in their quick runs to probe for shellfish. When the geese came sweeping in as winter approached he caught their wingbeats for all to see in his sketch notes.

Charles Tunnicliffe, Geese flying up the marsh (illustration from ‘Shorelands Summer Diary’)

In Shorelands Summer Diary Tunnicliffe wrote:

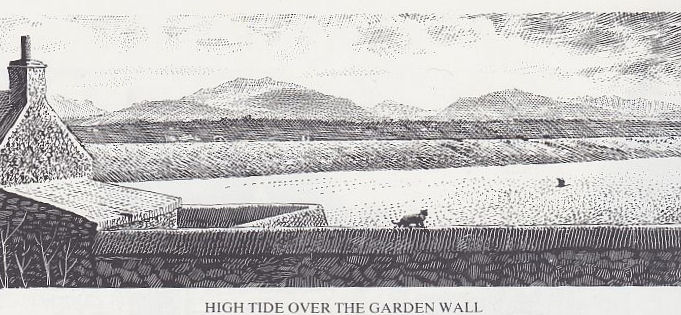

The house is well named ‘Shorelands” for only a stout stone wall and a row of rough upright timbers protect it from the tides of a mile-wide estuary. Years ago the estuary extended almost into the very heart of the island, but in the year 1812 a sea wall was built, and the inland area over which the tides used to flood was reclaimed and is now good farmland, dotted about with grey stone farmsteads, and intersected by numerous dykes and raised earth banks. The sea wall is called locally ‘The Cob’, and it has its beginning very close to the village at a spot where a bridge spans the river and its two flood-water canals. River and canals are disciplined by high man-made banks for some miles inland, indeed as far as the river is tidal. The bridge marks the end of the village street and the beginning of the road over the marsh. After crossing the bridge the road swings slightly inland, then deviates shorewards again and touches the Cob at its far end. Thus, between Cob and road, there is an area of brackish pool and swamp which is beloved of the birds, and both road and Cob make ideal vantage points for their study. Many are the happy hours I, have spent there. […]

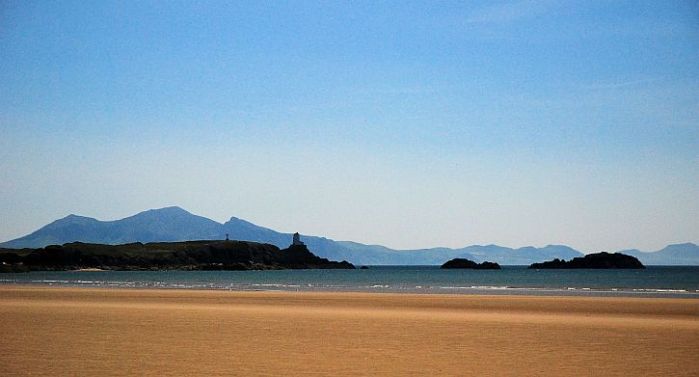

But to return home: the windows in the front of the house command views from east to south-west. Looking south-east, with the Cob extending across its whole width, is the mile-wide estuary. Beyond, filling the middle distance, is a long ridge of high ground criss-crossed by hedges and dotted about with farms, which at its seaward end deteriorates into rock and sand-dune, and above this ridge loom the great mountains of Caernarvonshire, the kingdom of Eryri, with Snowdon lording it over all – a stupendous panorama.

Charles Tunnicliffe, High tide over the garden wall (illustration from ‘Shorelands Summer Diary’)

We made our way back along the Cob – slowly, since everyone we met along the way seemed happy to stop and chat awhile. We paused, too, to observe the birds in the marsh, the school of great grey mullet in the Pool, and the horses that roam free across the marsh. Walking in this direction, the views of the distant mountains, seen above the pines of Newborough Forest, are stunning.

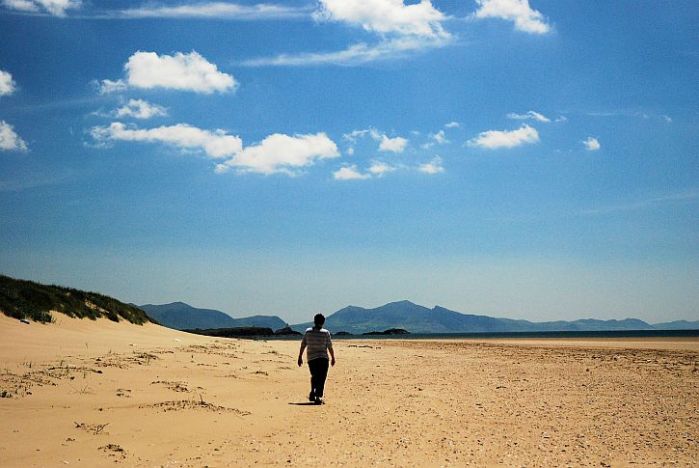

Cefni marsh and the distant mountains: as we saw it, and as Tunnicliffe drew it

Back at our staring point, the car park at the Newborough end of the Cob, we now set off to explore Cefni salt-marsh, following the Anglesey coastal path. The first stretch wound through shady woodland – very boggy in wet weather from the evidence of the extensive sections of duckboard provided.

A shady start to this section of the walk

After a mile or so, the path leaves woodland for the open salt marsh, following the edge of Newborough Forest. With tall Corsican pines to our left and acres of marram grass to the right, we followed the path as it continued along the edge of the estuary of Afon Cefni where clumps of tamarisk were in flower.

Out onto the saltmarsh, skirting the edge of Newborough Forest

Tamarisk was not the only flower to be seen along this stretch; as Charles Tunnicliffe observed on June 20th in Shorelands Summer Diary:

The dunes are full of flowers. Viper’s Bugloss stands in spires of blue as vivid as any delphinium; ragged robin blooms in delicate patches of pink, and in the damp places yellow iris is in flower. Hugging the sand the fluffy seed-heads of creeping willow mingle with heartease of an amazing variety of colours from deep blue through yellow to white. Among all this the Wheatears, both young and adult, fly round close to the ground, or perch on some dead stalk and utter their ‘Tcheck! Tcheck!’ flashing their pied tails as they take wing.

Out onto the saltmarsh

Soon we reached the point where the path turns south to follow the sand dunes that edge Penhros Traeth down towards the causeway out to Llanddwyn Island. By now the sun was at its zenith and it was blazingly hot. Although the saltmarsh and sandflats of the Cefni are important feeding areas for wildfowl and wading birds we saw very few. Only mad dogs and Englishmen…

Across the burning sand

When I was a kid, at home we had an old 78 of ‘Cool Water’, recorded by The Sons of the Pioneers in 1948, the year I was born. The words came flooding back as we toiled across the burning sands:

All day I’ve faced a barren waste

Without the taste of water, cool water

Old Dan and I with throats burnt dry

And souls that cry for water

Cool, clear, water

Keep a-movin, Dan, don’tcha listen to him, Dan

He’s a devil, not a man

And he spreads the burning sand with water

Dan, can ya see that big, green tree?

Where the water’s runnin’ free

And it’s waitin’ there for me and you?

It’s water, cool, clear water.

The wreck of the Athena on Traeth Penrhos

The tide was far out and we trudged on across an endless desert of scorching sand. Nearing Llanddywn Island we came upon the remains of a wreck, buried in the sand, but the ship’s spars exposed at low tide. This is all that remains of the Athena, a ship that ran into trouble during a winter storm in December 1852. It was sailing from Alexandria to Liverpool, and hadn’t got far to when it was wrecked upon this shore. Thanks to the courage of the local lifeboat men, the 14 crew of the Athena were rescued and taken to safety on Llanddwyn Island.

At last – cool water!

We were glad, eventually, to find a way through the dunes into the shade of the forest. With some difficulty we found our way back to our starting point through the bewildering maze of trails in the forest. Two thirsty walkers and one very thirsty dog!