There is one final art experience that I must write about before closing the book on our Nice jaunt last month. One day we caught a train along the coast to Antibes to visit the Picasso Museum there. Last time we were both in Nice, in 2008, we turned up at the Château Grimaldi only to find the museum closed for an extensive two-year renovation. I had been round the museum several years earlier with our daughter Sarah, after we had driven down from Castellane in the Provençal mountains where we were camping. Now, with Rita this time, I wanted to see how the Château Grimaldi’s impressive collection had been revamped.

The Museum is housed in the 17th century Château, built on the site of the ancient Greek city of Antipolis and of a Roman fort. The present building was a stronghold of the Grimaldi family from 1608 until it became Antibe’s town hall a hundred years later. It became the town’s art gallery in 1925.

We arrived on Sunday when a busy Provençal market is held in the market place just below the château: we wandered through stalls of fresh fruit and vegetables; lavender, herbs and spices; and delicious local patisserie. On the waterfront, a panel displayed an image of Picasso’s evocative painting, Night Fishing at Antibes (which isn’t here: it’s in New York, at MoMa). It was painted in August 1939, just as Europe was descending into the darkness of Total war for the second time in thirty years. Some have interpreted the painting, which shows two men spearing fish at night aided by a powerful lantern, as a companion piece to Guernica – an allegory of sudden death from above.

Picasso spent the war years in Paris, during the Nazi occupation. He returned to Antibes as soon as the war had ended – with a new lover, the young French artist Francoise Gilot. The works in the collection of the Museum are representative of the period of the late 1940s and early 1950s – one of great happiness and creativity in the artist’s life, in which he produced great works in both painting and ceramics.

The composition is based on Greek mythology; it depicts a tambourine-playing nymph, wild horse-like creatures, and fauns dancing and playing the duale – a double-barrel flute typical of this part of France. It refers to the story of Antipolis (the Greek name for Antibes) and is also a homage to Gilot, his muse of the time. La Joie de Vivre hangs on the second floor of the museum, in the space that became Picasso’s studio.

For the art critic Christine Vincendeau, this ‘Bacchanalia by the Sea’ (the title initially given to La Joie de Vivre by the Museum’s curator, Romuald Dor de la Souchère) is an homage to women, music and dance:

The scene takes place before the sea, identified by the yellow sail boat on the left. The central figure, a woman soaring upwards like rising sap, is dancing with two kid goats, a ballet accompanied by a flute-playing centaur on the right and, on the left, a faun playing the double flute. … The panel is divided horizontally about two-thirds up by black and blue coloured sections, with a yellow, grey, green and black foreground, which highlight the mother-of-pearl sky and its delicately iridescent touches. This composition emanates an impression of happiness, a ‘joie de vivre’ …. Picasso stands outside time, directly connected with his Mediterranean roots through the figures of Greek mythology, anchored in the archetypes of our unconscious. Location and date are indicated on the reverse: Antipolis 46, which is accompanied by a drawing depicting the head of a faun.[…]

This dance accompanied by music contributes to the overall meaning of the painting and …. confirms the feeling that filled him at the time. … The woman – also dancing – and taking part in the ballet forms the summit of the pyramid and the picture’s central axis […] is a representation of Françoise and is therefore the symbol and reality of a shared ‘joie de vivre’, a happiness, an unclouded transparency. The large faun on the right, seated and playing the double flute […] is the coryphaeus whose dual role is to impart a certain rhythm to the ballet and express the feelings of the crowd: it is he who brings the group alive. …

The background of the central decoration is represented by the colour blue – the sea – omnipresent in Antibes, ‘the ever-changing sea’; the foreground of yellow sand. All of the actors’ feet are set on the sand, their heads in the sky, except those of the two small dancing fauns.

The painting is interesting because of the materials Picasso used. So soon after the war, there was a shortage of art materials, so he worked with what he could get hold of locally. Instead of canvas, the panel is made of asbestos-cement, and the work is made using boat paint obtained on the quayside which Picasso applied using household paintbrushes.

When he moved into the studio, Picasso told the curator that in return he would decorate the walls of the castle. However, they were in a poor state of repair, so instead, he donated all the work he had completed there to the museum, stipulating that they should remain there permanently. Picasso came back to Antibes regularly, returning to the château the following year to paint Ulysses and the Sirens and little by little expanded the museum’s collection, donating ceramics he had made at the Madoura studio in Vallauris.

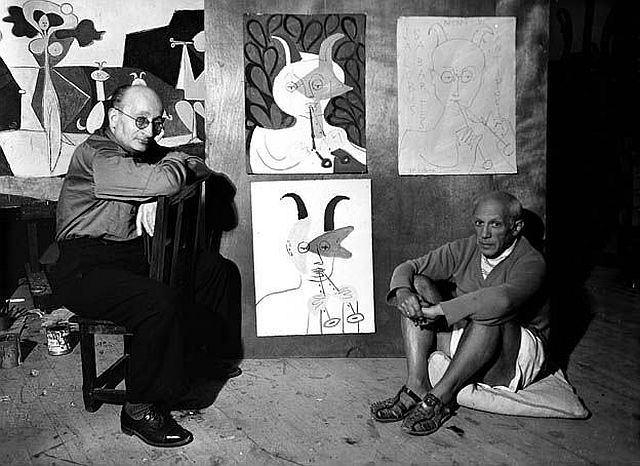

In June 1946 Michel Sima, the Polish sculptor and photographer, was asked by Picasso to photograph him at work in the studio at Château Grimaldi on a daily basis. The Museum today displays several of Sima’s evocative photographs alongside Picasso’s works. These include two photos in which Joie de Vivre appears – shown below. The first shows Picasso with his friend and personal secretary, Jaume Sabartés; the second with Francoise Gilot.

There is also a photo of Picasso with Sima, again in front of Joie de Vivre.

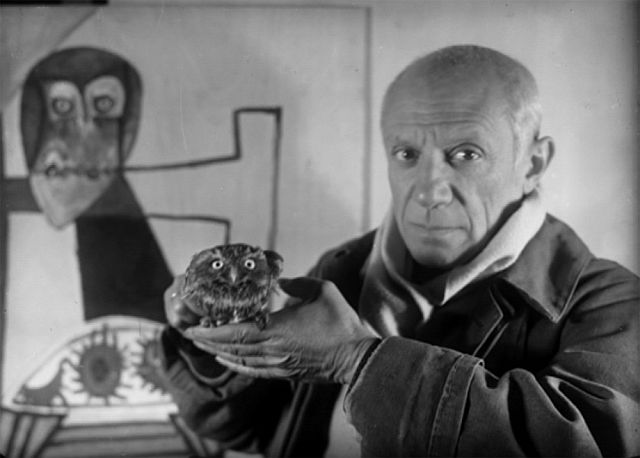

One of the best-known Sima photos of Picasso is the one which portrays him with a Little Owl which the artist kept after it had been found injured in the Château. It lived in a special cage in Picasso’s kitchen and inspired paintings, sculptures and ceramics featuring owls that he made at this time.

The collection of the Picasso Museum includes an important series of ceramic pieces made by the artist at the Madoura workshop in Vallauris from 1947 to 1949: painted sculptures (bulls, goats and owls), wittily decorated plates, dishes, vases, and glazed-tile paintings. They vary in quality, but the best of them demonstrate Picasso’s creative genius in fusing painting, sculpture and drawing into one form. The Madoura pottery where Picasso worked was owned by Georges and Suzanne Ramie; Vallauris, a few miles from Antibes, had been an important ceramics-producing town since Roman times. Picasso only work at the Madoura pottery for around two years, but in that time he produced more than 3,000 objects.

The newly-arranged exhibits include a striking display of decorated ceramic plates along one wall.

‘Few painters had shown an interest in pottery, giving it barely a second glance … and it was seen simply as a complementary activity’, Pierre Cabanne wrote in his biography of Picasso. But for Picasso, pottery proved a revelation, and above all he enjoyed the stimulus of a manual craft.

Picasso recalled the ceramics that were made in his home town of Malaga when he was a child. He drew on all he had seen there, and all he knew of the antique traditions of the Greeks. His technique was free, innovative and often provoked bewilderment amongst the workers at the pottery.

There’s a comprehensive display of Picasso ceramics on this Pinterest page.

The painting that most held our attention on this visit was Still life with Bottle, Sole and Ewer. It is thought to be the first work that Picasso created in the studio here. What makes it striking is the material it is painted on: Picasso used a panel of fibre cement, leaving some of the areas of cement unpainted. The material – matt and slightly grainy – seems to echo the colour and texture of the earthenware ewer and the tablecloth.

A strictly geometric composition, with the sole in its wicker basket being its central motif, it consists simply of the tablecloth, a bottle, the fish in the basket, a lemon and the ewer which he had found at a second-hand shop in Golfe-Juan. It’s a painting that has a simple beauty, with its shades of grey, ochre and white.

Here are three more iconic paintings from this productive period, each featuring aspects that dominated Picasso’s creative imagination at this time: Greek mythology, satyrs and fauns, fish and sea urchins, plants and the sea, and women, sensuality and music.

The paintings are framed as Picasso directed them to be, in black iron frames. The rooms are cool and calm, with the screened windows diffusing the bright Provençal sunlight in rooms that display this wonderful collection of Picasso’s ceramics and the drawings, paintings and prints.

Outside is a terrace that faces the sea. It has been turned into a sculpture garden with sculptures by Arman (Hommage a Picasso, 1982, a bronze collage of many guitars), Miro, Anne and Patrick Poirier (Jupiter et Encelade, 1983, a composition of five Roman heads of Carrera marble with an engraved bronze shaft of lightning), and Germaine Richier (La Feuille, 1948, a series of bronze figures).

Hello Gerry. And thank you for a wonderful article on your trip in south of France and to Picasso past studio and museum. It is well written and informative, as though one was there. I had not seen some of these work and images, especially the photos by Sima. As an artist myself it is exciting to touch in on Picasso’s world but also how it was. Just after the war, his use of available paint which limited his palette of colours , yet it shows how resourceful he was, and the paints he found are used beautifully. I have been transported back and I thank you. His painting s do reveal the joyful relief of war ending , sunshine and some optimism. Thanks again! ( more please ! )

Yours sarah

Thank you, Sarah. I’m glad you found the post worthwhile. It’s taken me three weeks of blogging to get that Nice trip and all the wonderful art we saw there out of my system. So if you do want more, scroll back through the recent posts and check out the stuff on Matisse, Chagall and co.

Bonjour Gerry

Je viens de voir vos articles qui sont très passionnant, pour un peu, je me serais bien retrouver dans ces merveilleux endroits.

Je fais une recherche bien spécifique, en quelle année le Tableau la Joie de Vivre a t elle été éditer par le musée et placarder dans Antibes pour annoncer une exposition ??

Affiche Antipolis ou la Joie de Vivre imprimeur Trulli

Impossible de trouver !!

Merci pour tout

Yolande – thank you for your kind remarks. Regarding your question, I will answer in English as my French is not good!

As I understand it, in 1946 after Picasso had been alerted to the possibility of space to carry on his work at the Chateau Grimaldi (by the photographer Michel Sima) he made a donation of works he completed during his time there that autumn to the museum – including Joie de Vivre. Françoise Gilot tells of this in her memoir, Life With Picasso (see this Guardian article: https://bit.ly/2zre1PG). There’s a catalogue for a 2009 exhibition at the museum called ‘Picasso 1945-1949 : L’ère du renouveau’ which it looks like you can get on Amazon.fr: https://amzn.to/2SaIx7B. There’s also this article from the New York Times in 1996: https://nyti.ms/2FIVGU9. This page on the museum seems to confirm that the paintings in Picasso’s donation went on display in 1947: https://bit.ly/2DM3sKl. I hope that helps, Yolande!

I heard a story regarding Joy of Life. Picasso has influenced and did this paint by a mausoleum which he saw it at a picture. The picture of that mausoleum was taken in antique city Nysa located in Aydin, Turkey. Do you know anything about it?

Bonjour Gerry,

Merci beaucoup pour cet article très intéressant sur lequel j’ai pu m’appuyer pour mon cours d’Histoire des Arts en lycée (le thème: “Picasso, passionnément méditerranéen”). J’ai vu qu’il y avait aussi un post sur Dickens, un des mes auteurs préférés: je vais aller le lire, cette fois juste pour le plaisir et non pour le travail! Cordialement

Merci beaucoup, Anne

Interesting blog, it reminds me of Picasso Museum in Paris. He was famous a Spanish painter, sculptor, regarded as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

I tried to write a blog about it, hope you also like it https://stenote.blogspot.com/2021/02/paris-at-picasso-museum.html

I have been a few times in the past to the museum in Antibes. I love the light in this part of France. No wonder artists wanted to paint there. I live in Scotland which does not get that light. I can’t wait to get back to South of France and try to paint.

Or California where one of my son’s live.

I am reading and learning more and more about the wonderful work by Picasso.