Marc Chagall in St Petersburg, 1910

It was what some cynics might call a day of typical Mancunian gloom. The mizzle was dreary and the light dismal as I stepped off the bus on Cheetham Hill Road and crossed over to the building that was my destination – a former synagogue that now serves as Manchester Jewish Museum.

With a history dating back two centuries, Manchester’s Jewish community is the second largest in Britain, one that grew rapidly during the first half of the 19th century as the city’s industrial growth attracted German-Jewish immigrants – shopkeepers and export merchants – as well as Sephardi traders from the shores of the Mediterranean. By 1851 there was a sizeable Jewish community, some of whom had begun to find homes in the semi-rural suburb of Cheetham Hill to the north of the city. In the next quarter century, three synagogues were established in Cheetham Hill, the last of them being the building I was making my way towards.

Manchester Jewish Museum, formerly the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue

In 1874, Jewish traders from Gibraltar, Aleppo and Corfu established the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue where a Sephardi, Ladino-speaking congregation would gather until the building became redundant as the Jewish population moved away from the Cheetham area. For a while, this must have been an intellectually vibrant community – just along the street stands another remarkable building – the former Cheetham branch of the Manchester Free Library, built at almost the same time as the synagogue, in 1876.

In Monday’s mizzle and gloom the area looked less than vibrant. It has that typical inner-city look of clearance and absence: an empty street grid suggesting the disappearance of swathes of terraced housing and of a community, now replaced by one-storey small industrial and retail units. There is evidence of the area being embraced by more recent migrants – on the next block Chappati Corner and Lahore Kebabish were doing good lunchtime business.

Inside the Manchester Jewish Museum

The old synagogue – a grade II listed building – re-opened as Manchester Jewish Museum in 1984 and tells the story of the Jewish community that settled here. Stepping into the main sanctuary, I spent some time studying its features, with the help of informative display panels and an enthusiastic guide who provided detailed answers to my questions.

The Torah scroll intended for Eichmann’s exhibition ‘Relics of a Defunct Culture’.

Stepping up to the bimah, the table from which the Torah is read, I found a Torah scroll displayed, one originally from Kutna Hora in Bohemia that formed part of a collection of Jewish religious items gathered by Adolf Eichmann in Prague in the 1940s and intended for an exhibition called ‘Relics of a Defunct Culture’. In 1964 Eichmann’s collection of 1,564 scrolls were brought to Westminster Synagogue in London. Most of the scrolls have since been distributed to Jewish communities across the world. This scroll is possul, blemished (not, I was told, because of its association with Eichmann, but because some of the words were now difficult to read, probably as a result of damp), so it cannot be used in a synagogue any more.

The Ark

With the Torah scroll before me, I looked across the hall towards the Ark – the most important part of the synagogue that contains the Torah scrolls. The original Ark was a gold box which held The Ten Commandments, given by God to Moses. Jewish communities across the world remember the original Ark with a replica in their synagogue. Instead of The Ten Commandments, a copy of the Torah is placed in the Ark and is covered with a pariochet (a curtain) just like the original.

Torah scrolls in the Ark

The Ark is on the eastern wall of the synagogue, since Jews face Jerusalem when they pray. Above the Ark is a stained-glass window with a design that incorporates a Menorah, the seven-branched lamp, symbol of Judaism since ancient times.

The synagogue’s stained-glass window with Menorah design

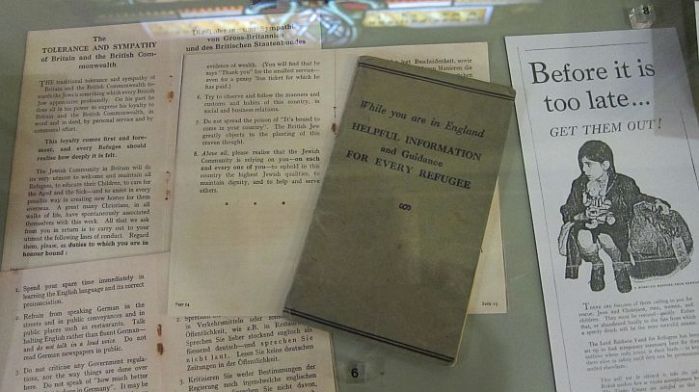

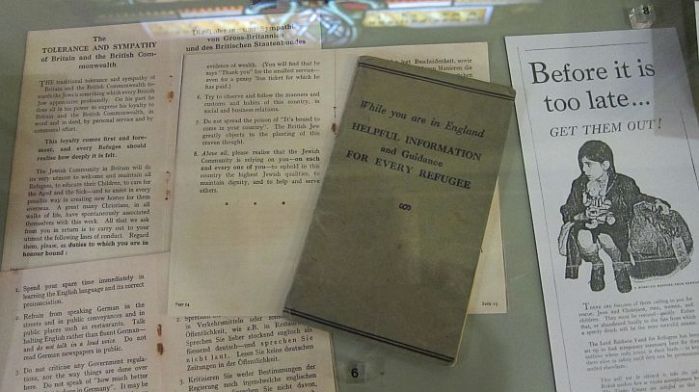

In an alcove I found a small display marking the anniversary of Kristallnacht, the night in November 1938 when the Nazis unleashed a series of riots against Jews in Germany and Austria. In only a few hours, thousands of synagogues and Jewish businesses and homes were damaged or destroyed.

Exhibits in the Kristallnacht display

The exhibits focussed on the limited numbers of Jews – mainly children – who were allowed to settle in this country in the months following Kristallnacht. There was a steamship ticket with which one individual had made the journey from Hook of Holland to Harwich, photos of children arriving in Manchester as part of the Kindertransport. The children were placed in British foster homes and hostels, often the only members of their families to survived the Holocaust. There was an example of a leaflet urging public support for the Kindertransport, and a booklet produced to help refugees adjust to British society.

Tearing myself away from these exhibits I made my way to a small back room where the reason for my visit was displayed – an exhibition of paintings by Jewish emigre artists who fled poverty and persecution in Russia to settle and work in Paris in the early 20th century. Entitled Chagall, Soutine and the School of Paris, the exhibition features work by Chagall and Chaim Soutine, and other early modernist pioneers who were part of the ‘School of Paris’, a group of Jewish artists who, because of their common background, tended to meet frequently and whose artistic output was shaped by their Jewish heritage.

The exhibition features around twenty works of art by 17 Jewish artists, all selected from the collection of Ben Uri Gallery at the London Jewish Museum of Art. These artists were either born within Russia, or in countries then within the Russian Pale of Settlement. In flight from the poverty, persecution and restrictions of their native lands, they converged on Paris, the ‘City of Light’ in search of personal and artistic freedom, mostly in the first two decades of the 20th century. The majority (among them Chagall, Dobrinksy, Henri Epstein, Lipchitz and Soutine) lived and worked together in the collection of studios known as La Ruche (‘the Beehive’) near the old Vaugirard slaughterhouses of Montparnasse. Many, probably including Ben Uri’s founder Lazar Berson, also studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, and exhibited at the progressive Salon d’Automne; together they had a profound influence on twentieth-century figurative art.

Many of these artists settled in France, and some applied for French citizenship. Then came the Second World War and the Nazi occupation which forced them into exile or hiding. Several were deported and died in the concentration camps.

Chaim Soutine, ‘La Soubrette’ (‘Waiting Maid’) 1928-33

One of the headline paintings here is Chaim Soutine’s, ‘La Soubrette’, acquired by the Ben Uri Gallery at London Jewish Museum of Art in 2012 – the first time the painting has been exhibited outside London.

Soutine was born in 1893 in a shtetl near Minsk, now in Lithuania, the tenth child of a poor Jewish family. He began drawing at a young age with encouragement from his family, but encountered opposition in his community for his defiance of the Talmudic interdictions concerning images. After he drew a portrait of the local rabbi he was so badly beaten by the rabbi’s son that he received substantial damages. He arrived in Paris in 1913, where he lived in extreme poverty at ‘La Ruche’ and studied at theEcole des Beaux-Arts.

Jackie Wullschlager, in the Financial Times, described Chaïm Soutine (along with Marc Chagall) as one of ‘the two greatest Jewish painters’ of the twentieth century. In the mid-1920s, Soutine made an important series of paintings of beef carcasses executed in an expressionistic style, influenced by Rembrandt and the Old Masters, painted direct from decaying animal carcasses hung in his studio, which were later to influence Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. His powerful character studies, which include pastry cooks, choirboys, boot boys, bell-boys and maids, dressed in the uniforms of their trade, strongly evoke the individual personalities of their sitters.

At the onset of the Second World War, Soutine – as a foreign national – was placed under house arrest. He died in 1943 and was buried in Montparnasse cemetery. Although Soutine has long been internationally recognised as one of the most influential painters of his generation, his work is poorly represented in UK public collections: the Tate holds three Soutine landscapes, but this is the only Soutine portrait in a UK public collection.

Focusing on a single subject in an unadorned background, the painting depicts an anonymous, working-class figure in the uniform of her profession. Soutine’s gesturally expressive manner and tactile brushwork betray his direct engagement with his subject, so that he underlines the maid’s individuality rather than reducing it, capturing an expression somewhere between weariness and resignation.

Marc Chagall, ‘Praying Jew’, c 1920

Chagall’s first oil version of the Praying Jew was executed in 1914, modelled on one of the old beggars with tragic faces, who wandered into his mother’s shop in Vitebsk. This figure, wrapped in Chagall’s father’s prayer shawl, was the most overtly religious of the series and was one of the artist’s own favourites. Its combination of a Jewish subject, largely realistically painted but set against an abstract background, brought the picture immediate acclaim when it was first exhibited in Moscow in 1915. This version is from a series of 100 lithographs executed some time around 1920.

Marc Chagall, The Horse and the Donkey, etching on paper, 1927

In 1927, Chagall began working on a project for the art dealer Ambroise Vollard – a series of etchings illustrating The Fables of La Fontaine, a classic text of 17th century France. The commission attracted controversy, with nationalist critics objecting to the ‘Russian’ (an, no doubt unstated, Jewish) painter interpreting a beloved French text. This compelled Vollard to defend his decision in an article: ‘Why Chagall? My answer is, simply because his aesthetic seems to me in a certain sense akin to La Fontaine’s, at once sound and delicate, realistic and fantastic’. Buoyed by Vollard’s unwavering support, Chagall undertook the commission.

Sonia Delauney, Invitation Card for Galerie Bing, Paris, 1964

A nearby exhibit may date from 1964, but there is a Chagall connection. In Paris before the First World Wasr, Chagall’s great friends were the painters Robert Delauney and his wife Sonia Delaunay. Sonia was born Sarah Stern in 1885 in Gradizhsk, Russia (now in Ukraine). She grew up in St. Petersburg exposed to music and art, and learned several foreign languages. In 1905, she travelled to Paris, studying and discovering the work of Cézanne, Van Gogh, Pierre Bonnard, and Edouard Vuillard, as well as Matisse and Derain. In 1908 she married the German collector and art dealer, Wilhelm Uhde. Through Uhde, Sonia encountered many painters, including Robert Delaunay who she married in 1910, after divorcing Uhde by mutual agreement.

Together Sonia and Robert Delaunay pursued the use of abstract colour in painting and textile design. They were ardent promoters of abstract art in succeeding decades, and in 1964, after becoming the first living female artist to have a retrospective at the Louvre, the Galerie Bing mounted a solo show of Sonia’s work – for which she produced the striking abstract design for the poster and invitation card, included in this exhibition.

Isaac Dobrinsky, ‘Head of a Girl’, c 1952

Isaac Dobrinsky’s father was a religiously observant Jew who made sure that his son was brought up in a traditional way: he studied in a heder (Jewish elementary school) and in a yeshiva (Jewish high school). Attracted to art, Dobrinsky moved to Kiev to study sculpture. In 1912, he won a prize for his sculpture which allowed him to move to Paris where he lived until his death in 1973.

Dobrinsky spent the Second World War in hiding in southern France, returning to the capital in 1945. In 1950, he was invited by the founders of a home in Limousin which cared for children orphaned by the Nazis to paint portraits of the children. In the course of two years, Dobrinsky worked on about forty portraits of young boys and girls.

In Head of a Girl, Isaac Dobrinsky has portrayed a young girl, tight-lipped and with a blank stare. In contrast to her dark expression and bare surroundings, he uses a light, luminous palette and lively brush-strokes to capture her individuality.

Leon Bakst, ‘La Peri’, 1911

Léon Bakst was born in 1866 in Grodno (Hrodna, now in Belarus) and studied at the St. Petersburg Academy and then in Paris before beginning his career as a magazine illustrator. After travelling through Europe, he returned to St Petersburg, and in 1906 became a teacher of drawing at a private art school where, among other students, he taught Chagall.

Rebelling against the dull and literal stage realism of the previous century, Bakst turned his painting skills to theatre design and in 1909 Bakst began a collaboration with Diaghilev, which resulted in the founding of the revolutionary Ballets Russes, of which Bakst became artistic director. His stage designs quickly brought him international fame. Most notable are his costume designs for The Firebird and Sheherazade (both 1910) and L’Apres-midi d’un Faune (1912). In 1910 Bakst was exiled from St Petersburg (as a Jew without a residence permit) and settled in Paris, where he died in 1924.

La Péri was commissioned by Diaghilev for the Ballets Russes in 1911 for a ballet composed by Paul Dukas. Bakst’s drawing evokes a sense of rhythmic movement enhanced by the exoticism of his decorative costume.

Henri Epstein, ‘Forest of Rambouillet’, c 1931

Henri Epstein was born in 1891 in Lódz, Poland. His father died when he was three and he was raised by his mother who encouraged his interest in painting. He studied drawing in Lódz, then the School of Fine Arts in Munich. Epstein visited Paris in 1912 before serving in the Polish army, then returned to Paris and settled at La Ruche from 1913-38.

Although Epstein’s early art work was influenced by fauvism, he later adopted an expressionist technique. His work, lavishly and vividly painted, depicts landscapes, peasants working in the fields, fishermen at work, interiors, portraits, and nudes. Epstein lived for a time near the forest of Rambouillet, west of Paris and in this painting employs a predominantly green palette, free brushstrokes and generously applied paint to create a textured and vivid surface typical of his later expressive style.

Epstein bought a farm near Epernon, which became his refuge during the Occupation, until on 23 February 1944 he was arrested by Gestapo agents. Despite appeals by his wife and his friends, Epstein was sent to Drancy camp on 21 February 1944. He was deported on 7 March in convoy number 69 and killed in Auschwitz.

Chana Kowalska, ‘Shtetl’, 1934

Kowalska was born in Wlockawek, Poland and was the daughter of a rabbi. She started drawing at the age of 16 and became a school teacher at the age of 18. In 1922, she moved to Berlin and later to Paris. She worked as a journalist and wrote articles about painting for Jewish newspapers. In the Second World War, during the German Occupation of France, she worked for the French Resistance. Arrested by the Gestapo, she was first imprisoned with her husband, then deported and shot by the Nazis in 1941.

In Shtetl Kowalska depicts the traditional Jewish small town with its tightly-knit community common throughout Eastern Europe before the Holocaust. Neighbours gather round the water pump at the town’s centre while a horse-drawn cart winding up a street lined with traditional, single-storey houses records a way of life that was soon to disappear. Already in Kowalska’s vision, pavements, telegraph poles and street lights signify the arrival of modernity, while the dome in the distance suggests continuing tradition. Many of Kowalska’s paintings recall her homeland and their folk-like quality, bright colours and unnatural perspective suggest the influence of Chagall.

See also

53.410777

-2.977838