While we were in London recently we went to the Imperial War Museum to see Truth and Memory: British Art of the First World War. It’s billed as being the largest exhibition of British First World War art for almost 100 years, and there is certainly a great deal to absorb. I’ll review what for me were the highlights in this and two succeeding posts. As its title suggests, this retrospective encourages us to think about how artists represented the war, and helped commemorate it – but also, how their work still affects our perception of it a century later.

The display is split into two: one suite of galleries given over to ‘Truth’, the other to ‘Memory’, though at times it’s not clear how precise the allocation of works is in reality. This is a large exhibition, with each section containing around 50 works,

Truth

Walter Sickert, The Integrity of Belgium, 1914

The first things you see in this part of the exhibition are two paintings that illustrate official British sentiment at the start of the war. William Barnes Wollen’s large Death of the Prussian Guard (1914) presents the first battle of Ypres as a moral triumph over Prussian militarism. Walter Sickert’s Integrity of Belgium, painted late in 1914, endorses support for ‘gallant little Belgium’ in its noble and glamorous depiction of physical warfare.Both paintings support the justification of British involvement in the war in defence of Belgium and in opposition to German militarism.

The rest of the gallery portrays the conflict in very different terms. The war brought about an enormous shift in art since it was a conflict depicted by the soldiers themselves. As a result, their work carried with it the weight of authenticity. Two rooms feature works by Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson and Paul Nash, both appointed official war artists in 1917 for the Department of Information. This represents an outstanding selection of works (both paintings and prints) by the brilliant CRW Nevinson, including his famous painting of a machine-gun post, La Mitrailleuse. Central to his vision of the war was his depiction of man dominated by the machines of war.

CWR Nevinson, La Mitrailleuse, 1915

Nevinson had been associated with the Italian Futurists before the war, collaborating with the movement’s founder Filippo Marinetti on the 1914 English Futurist Manifesto. Marinetti had promised to ‘glorify war -the world’s only hygiene – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers.’

CWR Nevinson, A Bursting Shell, 1915

To begin with, therefore, Nevinson sought to glorify the war as a triumph of technical achievement. However, his style changed after he had experienced the horrors of the front. The ‘essence of the new war,’ he said, ‘was overwhelmingly extremely alien, and utterly un-heroic.’

CWR Nevinson, French Troops Resting, 1916

Nevinson provided some of the most vivid responses to the war. Initially optimistic, his view and his painting style soon changed. Futurist dynamics had helped him depict the inhuman machinery of conflict but later, when depicting the death of a child or British soldiers’ corpses, he adopted a more sympathetic realism, exemplified by French Troops Resting and The Doctor.

CWR Nevinson, The Doctor, 1916

Of The Doctor, Nevinson wrote, ‘This picture, quite apart from how it is painted, expresses an absolutely NEW outlook on the so-called ‘sacrifice’ of war which up to the present is only felt by privates and a few officers’; while commenting on his image of a dead child in A Taube (1915), completed in Dunkirk after an air raid, Nevinson said: ‘there the small body lay before me, a symbol of all that there was to come.’ Interviewed by the Daily Express, he stated:

Here our ways part … Unlike my Italian Futurist friends, I do not glorify in war for its own sake, nor can I accept the doctrine that war is the only health giver … In my pictures … I have tried to express the emotion produced by the apparent ugliness and dullness of modern warfare.

CWR Nevinson, Ypres after the First Bombardment, 1915

CWR Nevinson, A Taube, 1916

CWR Nevinson, Paths of Glory, 1917

Nevinson’s depictions of death, like the portrayals of destruction by Paul Nash that hang alongside them, are apocalyptic. Paths of Glory (1917) with its depiction of the putrefying bodies of two British soldiers lying face down in no man’s land was banned from public display.

CWR Nevinson, Marching Men, 1916 pastel

CWR Nevinson,, Flooded Trench on Yser, 1916

CWR Nevinson, Southampton, 1916

CRW Nevinson, Boesinghe Farm, 1916

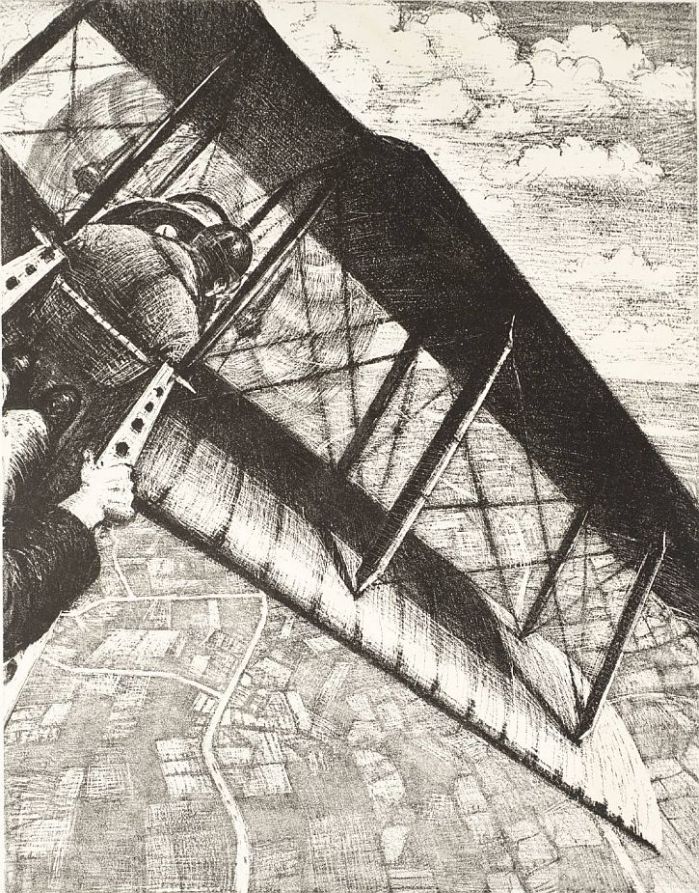

Commenting on Nevinson’s work, a Times reviewer wrote of it depicting ‘a nightmare of insistent unreality, untrue but actual, something that certainly happens and yet to which our reason will not consent’. Nevinson’s paintings and lithographs conveyed the essence of a new kind of war – overwhelmingly new and utterly unheroic. Nevinson’s series of 1917 lithographs, ‘Britain’s Efforts and Ideals’, were a final expression of his fascination with flight and aerial viewpoints.

CWR Nevinson, Swooping Down on a Taube

CWR Nevinson, Banking at 4000 Feet

CRW Nevinson, Nerves of an Army, 1918

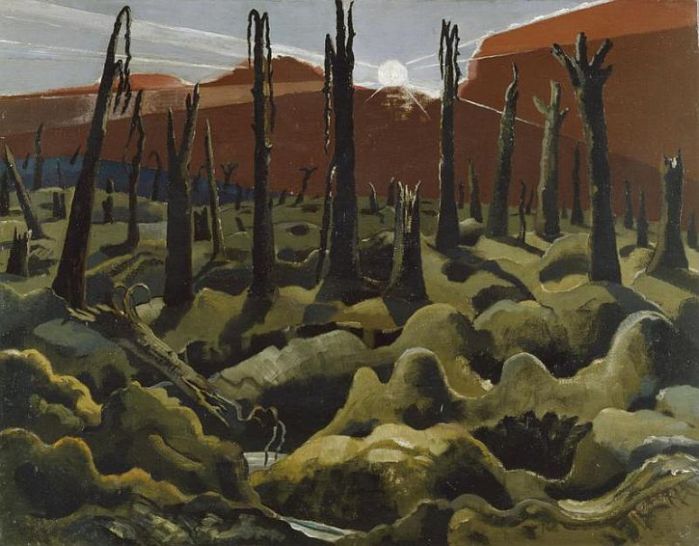

Other artists, such as Paul Nash, concentrated on the shattered landscapes of war, peopled by equally shattered combatants. Trees came to figure repeatedly in Paul Nash’s depiction of the destruction wrought by war. A passage from a letter written in 1912, explains the outlook that underlay his distinctive approach:

I have tried to paint trees as tho’ they were human beings … because I sincerely love & worship trees and know they are people & wonderfully beautiful people…

Across Flanders and Picardy, the woods that offered vantage and protection were ripped apart by the opposing forces. Nash wasn’t the only one to be deeply affected by their destruction. One soldier later wrote in his memoir of the war:

I never lost this tree sense: to me half the war is a memory of trees; fallen and tortured trees; trees untouched in summer moonlight, torn and shattered winter trees, trees green and brown, grey and white, living and dead. They gave their names to roads and trenches, strong points and areas. Beneath their branches I found the best and the worst of war.

Paul Nash, The Mule Track, 1918

Paul Nash, We Are Making a New World, 1918

In his excellent study, A Terrible Beauty: British Artists in the First World War, Paul Gough noted how, on trench maps, ‘the very words – ‘copse’, ‘wood’, even ‘forest’ – soon became irrelevant as trees were felled by artillery shells, reduced to splinters, charred by fire, and felled for military use’. he continues:

Nash saw all this. In the Ypres Salient he was aghast at the sight of splintered copses and dismembered trees, seeing in their shattered limbs an equivalent for the human carnage that lay all around or even hung in shreds from the eviscerated treetops. In so many of his war pictures, the trees remain inert and gaunt, failing to respond to the shafts of sunlight; their branches dangle lifelessly.

A series of melancholy chalk and watercolour drawings by Nash watercolours displayed in the exhibition make the point.

Paul Nash, Chaos Decoratif, 1917

Paul Nash, Broken Trees, Wytschaete, 1917

Paul Nash, The Field of Passchendaele, 1917

Paul Nash, Ruins of the church at Mont St Eloi, 1917 (Source: Imperial War Museum)

Paul Nash, Sunset Ruin of the Hospice, Wytschaete (Source: Imperial War Museum)

Paul Nash, The Ypres Salient at Night, 1918

Paul Nash, Spring in the Trenches, Ridge Wood, 1917

There are several paintings here by Paul Nash’s younger brother, John.He enlisted in the Artists’ Rifles in September 1916, and was serving in France only two months later. He was attached temporarily to a unit at Oppy Wood until April 1917, before being transferred to the Second Battalion to take charge of nine men who took part in the disastrous attack on Marcoing in December 1917. These experiences are documented in the two brilliant oil paintings exhibited here.

Paul Nash, Oppy Wood, 1917. Evening

John Nash, ‘Over The Top’. 1st Artists’ Rifles at Marcoing, 30th December 1917

The Vorticists

We have already had a healthy serving of Nevinson, but here is a room devoted to the Vorticists. It’s dominated by Wyndham Lewis’s mechanical ballet, A Battery Shelled, but there are fine works here, too, including William Roberts’ atmospheric ‘Feeds Round!’ Stable-time in the Wagon-lines, France, and work by David Bomberg and John Duncan Fergusson.

William Roberts, ‘Feeds Round!’ Stable-time in the Wagon-lines, France, 1922

William Roberts’ painting gets its name from ‘Feeds Round!’, the order given by the Sergeant Major for the men to cease grooming. The nose-bags are then brought and placed just behind each horse where the men wait in readiness for the final order, ‘Feed!’

David Bomberg, Study for The Billet, 1915

In Billet Bomberg uses line in a novel way, constructing the planes of the composition from a dense mesh of parallel or crossed straight lines.

John Duncan Fergusson, Dockyard Portsmouth, 1918

Dazzle marine camouflage transformed the look of British dockyards during the First World War (during the recent Biennial in Liverpool, the historic pilot ship the Edmund Gardner in Canning Graving Dock opposite the Museum of Liverpool, was transformed into a ‘dazzle ship’). John Duncan Fergusson was struck by the dynamic mixture of bright colour and abstract shapes which replaced the sober greys of pre-war shipping. His painting is a celebration of this unusual aspect of the docks and his work is much more involved with the formal concerns of shape and colour than with the wartime setting. The painting is dominated by massive machinery, given scale by the small figures in the dinghy and on the far dockside.

Percy Wyndham Lewis, A Battery Shelled, 1919

Inspired by his experiences as an officer in the Royal Garrison Artillery, Percy Wyndham Lewis here depicts the effects of counter-battery artillery fire. A British position is bombarded by accurate German fire; the heavily stylised figures of British gunners seem to form part of a mechanical structure as they struggle to move shells to their guns. The three gunners in the foreground appear almost like spectators, their fatalistic and calm detachment reflecting the impersonal nature of artillery warfare.

The painting reflects Wyndham Lewis’s thoughts on effect of modern warfare, seeing the gunners as dehumanised, insect-like, scuttling for survival. He likened the war to an absurd nightmare removed from everyday reality, a surreal spectacle of chaos. The exhibition curator, Richard Slocombe, adds:

This is an intriguing way of producing a modern history painting. It reveals the mindset of some of the vorticists during the war. Before the war they wanted to overturn the conventions and traditions of the day but the art that emerged is much less machine oriented and more humane. Wyndham Lewis commented on the debasement of humanity in wartime, that there is this collective dynamic which reduces the individual to a kind of cog in a bigger machine. Here, you have these figures reduced to quite primitive muscular forms.

Memory

‘Memory’ focuses on art produced towards the end of the war and in its immediate aftermath. For those in power, the central role envisioned for British art was that it would commemorate the war by conveying the legitimacy of Britain’s cause and the nation’s sacrifice.

Eric Kennington, Kensingtons at Laventie, 1915

Kensingtons at Laventie, was painted by Eric Kennington as a tribute to his soldier comrades shortly after he had been invalided out of the war. Paintings such as this confirmed the increasing importance of the war as a subject for artists.

The painting derives from Kennington’s experience of front-line duties during the bitterly cold first winter of the war. It recalls the moment when his exhausted platoon, having endured four days and sleepless nights in the trenches, with persistent snow and temperatures as low as minus 20C,arrived at the at the ruined village at Laventie, northeast of Béthune.

Exhibited for the first time in April 1916, the painting was an immediate sensation. Hailed as ‘decidedly the finest picture inspired by this war as yet produced by an English artist’, it was instrumental in securing Kennington the role of an official war artist in August 1917. It is a highly democratic image, too: its composition arranged to focus on the bravest and best fighters of Kennington’s platoon regardless of rank.

Art’s role in the national conversation was affirmed in May 1916 when The Times newspaper published an article proposing that artists from ‘within and without the [Royal] Academy’ be despatched to the fighting front so that:

Britain might thus become possessed of worthy memorials to the greatest epoch in the country’s history, and a true Renaissance of Art might be brought about under the stress of a noble and all pervading emotion.

It was only in March 1918, with the formation of the British War Memorials Committee, that a state art scheme was established for a national memorial. This was indicative of a wider mood of reflection that had already resulted in the setting up of the Imperial War Museum in March 1917.

The Committee’s outlook was both radical and modern. It sought to represent the full sspectrum of British art. Special provision was made for younger modernist artists ( causing its chairman, the novelist Arnold Bennett to describe the scheme as ‘a conspiracy in aid of good painting, and of good new painting in particular’. This and the insistence that all paintings should be based on actual experience invited some intensely personal interpretations of the war.

The exhibition features several of the paintings commissioned under the scheme, including John Singer Sargent’s monumental Gassed. That work is in a room easily missed which contains several sculptures of note, including Charles Sargeant Jagger’s huge plaster relief of The Battle of Ypres, as well as John Singer Sargent’s harrowing master-work.

Perhaps the most surprising figure here, however, is William Orpen: the society portraitist who became a painter of bone-white landscapes populated with unburied corpses and the detritus of battle. I’ll devote a separate post to these paintings, and another one to the prints of Percy John Delf Smith, an artist unknown to me before this show. His ‘Dance of Death’ series echoes Holbein and Dürer in employing the medieval allegory of the universality of death to express the macabre lottery of life on the Western Front.

For myself, the best paintings in this section are those by Stanley Spencer and Henry Lamb.

Henry Lamb, Irish Troops in the Judean Hills Surprised by a Turkish Bombardment, 1919

Henry Lamb was Stanley Spencer’s friend and mentor. His Irish Troops in the Judean Hills is one of few British war paintings not to depict the western front, and one of the few official paintings of the Mediterranean campaign commissioned by the War Memorial Committee. Its elevated viewpoint shows an encampment under bombardment at an hour before evening ‘stand to’. Dense clouds of smoke drift across the scene from exploding shells. Soldiers run and attempt to shelter from the bombardment, while two soldiers carry a wounded soldier in the lower right of the composition.

This is one of a series of paintings commissioned by the British War Memorial Committee set up by the Ministry of Information early in 1918. The Committee developed a scheme to build a ‘Great memorial gallery’ devoted to ‘fighting subjects, home subjects and the war at sea and in the air’. However, the Hall of Remembrance was never completed and the collection was given to the Imperial War Museum. Henry Lamb was serving in the Egyptian Expeditionary Force when he was approached by the Committee in February 1918. He was unable to start work on the painting until after he demobbed in March 1919.

Arthur Neville Lewis, Artillery Drivers in the Snow, 1918

Arthur Neville Lewis was a South African artist who trained at the Slade. He was conscripted in 1916 and served on the Italian front during an Alpine winter.

Stanley Spencer, Travoys Arriving with Wounded, September 1919

Spencer’s Travoys is a bold painting representing a scene he witnessed during his service with the 68th Field Ambulance in Macedonia. It shows mule-drawn stretchers bearing wounded men to a dressing station in an old Greek church. There is a passage from dark to light Both the horses, ears erect, and the men are watching the lifesaving efforts of surgeons in a makeshift operating theatre. More casualties are being delivered from the top-right corner of the painting, ‘creating a sweep of movement that pulese through the composition’ (Paul Gough). At its centre, the surgeon’s hand closes eyes of a recently deceased soldier. Spencer saw this as a religious painting, ‘a scene not of horror but of redemption. It is intended to convey a sense of peace in the middle of confusion’.

Forgotten Fronts

This interesting section of the exhibition presents unusual representations of women at work in the munitions industries which are themselves the work of female artists.

Despite the contribution of over 1.6 million British women to the national war effort and the British War Memorials Committee’s promise of an all-encompassing national memorial of ‘fighting subjects, home subjects and the war at sea and in the air’, the areas of female service were under-represented by the scheme.

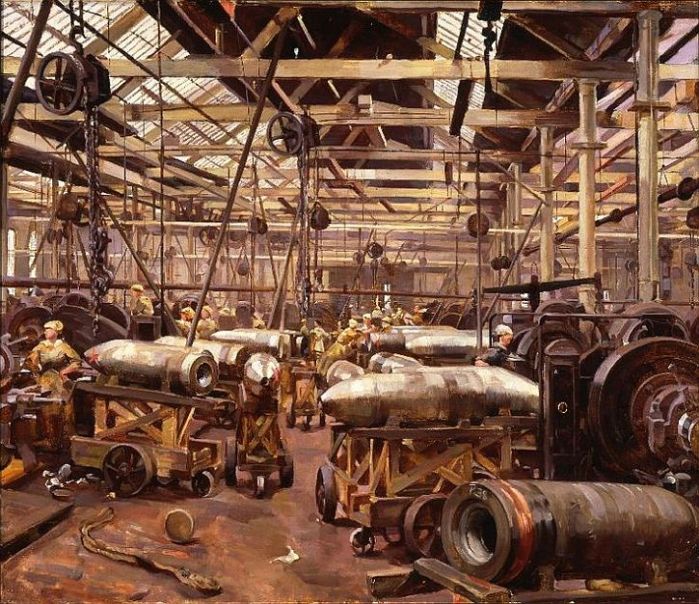

Anna Airy, Shop for Machining 15″ Shells, Clydebank, 1918

The Committee also overlooked many female artists. For the three who were commissioned – Anna Airy, Flora Lion and Dorothy Coke – the experience was humiliating. The Committee acquired none of their work. For Airy the ignominy of having her memorial painting rejected was so great that she destroyed it.

There was some compensation for Airy in 1918 when she was appointed by the Munitions Committee of the Imperial War Museum to record industrial production. Later commemoration of women’s war service came with the creation of the Women’s Work Section at the Imperial War Museum in 1918.

Anna Airy was commissioned to produce four paintings depicting munitions production at a crucial stage in the First World War when the tactical use of heavy artillery had become central to the success of the Allied forces. The success of Scottish heavy industry was built on low investment and cheap labour and Anna Airy gives some indications of this in Shop for Machining 15″ Shells, Clydebank. The handling equipment is basic and the production lines disorganized. Indeed, workers at the Singer factory had held a major strike in 1911, their grievances encapsulated in the slogan: ‘An injury to one is an injury to all’. The painting measure how far the war economy had developed and society changed: a household name in domestic consumerism was now producing armaments, and women, who might previously have been employed in domestic settings, are now employed on their factory floor.

Anna Airy, An Aircraft Assembly Shop, Hendon, 1918 (© IWM (Art.IWM ART 1931)

This is one of four commissioned paintings, depicting munitions production at a crucial stage in the First World War. In An Aircraft Assembly Shop, Hendon the scene is the interior of the Aircraft Manufacturing Company erecting shop with DH9 planes in various stages of production. Workers are grouped together according to trades. The layout represents the first tentative moves towards the mass production methods developed by Henry Ford in the United States.

Flora Lion, Building Flying Boats, 1918 (© IWM (Art.IWM ART 4435)

The interior of an assembly shed at an aircraft factory in Bradford. On the left is an aircraft under construction. In the right of the composition workers stand at benches planing and fixing pieces for the aircraft. Their jackets are hung on pegs on the right that run the length of the factory wall. Flying boats (designed with a boat-like fuselage for landing and take off from water) were used extensively by the British during World War One, notably for spotting German U-boats.

Flora Lion, Women’s Canteen at Phoenix Works, Bradford, 1918 (© IWM (Art.IWM ART 4434)

Flora Lion was given access to paint factory scenes in Leeds and Bradford during World War One. In this painting she depicts the interior of the canteen, filled with women workers who sit, chat and queue for food. Many are noticeably tired. The couple in the centre, arms entwined, dominate the scene and embody the confidence of women newly liberated by employment.

Truth and Memory is a comprehensive and absorbing exhibition that offers the rare experience of seeing together in one place a great selection of First World War art by British artists. I’ll devote two further posts to the exhibits: one to the work of William Orpen, and another to the prints of Percy John Delf Smith. The IWM exhibition complements a more wide-ranging show of war art from the First World War and other conflicts at Manchester Art Gallery.

See also

- At the Imperial War Museum (2): The disturbing vision of William Orpen

- At the Imperial War Museum (3): Percy Delf Smith’s ‘Dance of Death’

- The oils of war: Waldemar Januszczak’s blogged preview of the exhibition

- World War I remembered through British art: exhibition review on World Socialist Web Site

- Otto Dix’s War: unflinching and disturbing, but dedicated to truth

- Kathe Kollwitz’s ‘Grieving Parents’ at Vladslo: ‘Seed Corn Must Not Be Ground’

- The Art of War

- A Terrible Beauty: British artists in the First World War

- Stanley Spencer’s Sandham murals: ‘a heaven in a hell of war’

- Paul Nash and World War One: ‘I am no longer an artist, I am a messenger to those who want the war to go on for ever… and may it burn their lousy souls’

- The Great War in Portraits: patriotism is not enough

- History and war in the 20th century: a storm blowing from Paradise

- Leeds art: pain, war, atonement and dance

Was/is Paul Nash to art what Edward Thomas was/is to poetry?

I think so.

EDWARD thomas was my great Uncle he died 100 years ago on the 1st day of the battle of Arras.

I am a big fan of Nash I must say