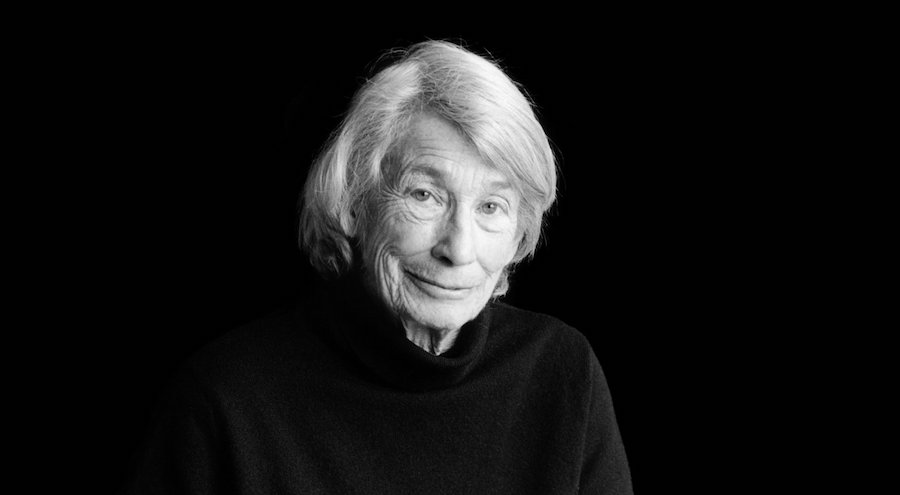

The poet Mary Oliver, who has died at the age of 83, wrote some of the poems I cherish most. Born in 1935 in a small Ohio town, she often found escape from a hard childhood and an abusive father by walking in the woods. “It was a very bad childhood for everybody, every member of the household, not just myself I think. And I escaped it, barely,” she later said. But I got saved by poetry. And I got saved by the beauty of the world.”

That experience was distilled in one of her finest poems, The Journey:

One day you finally knew

what you had to do, and began,

though the voices around you

kept shouting

their bad advice –

though the whole house

began to tremble

and you felt the old tug

at your ankles.

“Mend my life!”

each voice cried.

But you didn’t stop.

You knew what you had to do,

though the wind pried

with its stiff fingers

at the very foundations,

though their melancholy

was terrible.

It was already late

enough, and a wild night,

and the road full of fallen

branches and stones.

But little by little,

as you left their voices behind,

the stars began to burn

through the sheets of clouds,

and there was a new voice

which you slowly

recognized as your own,

that kept you company

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could do–

determined to save

the only life you could save.

Following in the footsteps of Whitman and Thoreau, Oliver’s poetry is grounded in her close observation of the natural world and a deep sense of being in the world as a kind of spiritual experience, as she wrote in A Summer Day:

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

And she was driven to contemplate the harm humans had caused to the world:

I think it is very very dangerous for our future generations, those of us who believe that the world is not only necessary to us in its pristine state, but it is in itself an act of some kind of spiritual thing. I said once, and I think this is true, the world did not have to be beautiful to work. But it is. What does that mean?

Despite being one of the most popular and garlanded of modern American poets (in 1984 her collection American Primitive won the Pulitzer Prize), Oliver has often not been taken seriously as a writer. But for me she was one of the best.

– Wild Geese

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

Who made the world?

– The Summer Day

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean—

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down—

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

When death comes

– When Death Comes

like the hungry bear in autumn;

when death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse

to buy me, and snaps his purse shut;

when death comes

like the measle pox;

when death comes

like an iceberg between the shoulder blades,

I want to step through the door full of curiosity, wondering:

what is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness?

And therefore I look upon everything

as a brotherhood and a sisterhood,

and I look upon time as no more than an idea,

and I consider eternity as another possibility,

and I think of each life as a flower, as common

as a field daisy, and as singular,

and each name a comfortable music in the mouth

tending as all music does, toward silence,

and each body a lion of courage, and something

precious to the earth.

When it’s over, I want to say: all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was a bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.

When it’s over, I don’t want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself sighing and frightened

or full of argument.

I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world.

One of my faves too. Thanks for remembering her.

Thanks for the introduction Gerry, I’ll look for her work in the library.

One thing, in 1984 she would have turned 49.

Thanks for the correction – part of that sentence went in the editing – she was 28 when her first collection was published.

Lovely tribute, with a poignant selection of her poems. Thank you.

Thank you,Gerry. Poems to treasure.

Great post … from the heart as usual. Need to share with you the story of John Longstaff, the subject of the latest album from the trio “The Young’uns”. Just found them and blown away by the work, setting the story of Johnny’s upbringing and time in the Spanish Civil War. Am currently listening to the recordings he made for the Imperial War Museum (over 3 hours). Where have those brave souls who have beliefs and the conviction to do something about it !!!!!

Thanks, John. I read about Johnny Longstaff and the Young ‘Uns album in the Guardian. Sounds excellent (https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/feb/04/johnny-longstaff-a-forgotten-hero-the-spanish-civil-war-fighter-the-younguns-folk)

I enjoyed these poems. A very soothing quality to her voice for me. Thanks

when death comes: brave, supportive…

thanks for posting

I’ve just discovered your blog (via Barnaby Rudge) and it’s a real discovery. This Mary Oliver piece is a great introduction to a poet I’d never read. I do hope you haven’t stopped working on the blog? Thanks prospectively anyway.

Thanks so much. Unfortunately, yes – I have discontinued the blog. But what I posted for 8years or so remains here, and you are welcome to peruse!