TS Eliot once said that the meaning of a poem exists somewhere between the poem and the reader. The comment seemed apposite as I sat in the third room of the breathtaking Anself Kiefer retrospective at the Royal Academy surrounded by monumental artworks that spoke to me powerfully, though why they did I knew would be more difficult to articulate.

Perhaps rational explanations are unnecessary, and we should simply allow ourselves to feel instead. Sophie Fiennes, who directed a brilliant, impressionistic documentary about Kiefer called Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow, said that her film revealed how an artist thinks about being an artist: ‘which is that you have the liberation from having to explain yourself because you’re working with sensation’.

I knew enough of the Kiefer story before I came to have an inkling of what to expect: the boy born into the ruins of Hitler’s Thousand-Year Reich, and the artist whose work came to be consumed by the weight of his nation’s history and the guilt of the Holocaust. I knew, too, that he worked on a large scale and in a variety of materials and media, and that when he did paint he threw literally anything at the canvas. But none of that knowledge prepared me for the overwhelming experience of seeing my first solo Kiefer exhibition. Nor was I prepared for the beautiful landscape paintings which fill the penultimate room, and the sheer breadth of questions about human history, deep time and our place on the planet that Kiefer explores in his work. Kiefer’s themes were, I think, brilliantly summarized in the title of last week’s Imagine documentary about the artist: ‘Remembering the Future’.

Kiefer was born amidst ruins on 8 March 1945 in Donaueschingen, a town in the Black Forest region which was both a rail hub and the base of a military garrison. As the town came under intense Allied bombing, Kiefer was born in the cellar of the family home that served as their improvised bomb shelter. In the first few weeks of his life his mother would take him during the day into the surrounding forest to shelter from the bombing. The house next door was blown to pieces. In his essay ‘Air War and Literature’, the WG Sebald writes:

Of the 131 towns and cities attacked, some only once and some repeatedly, many were almost entirely flattened … about 600,000 German civilians fell victim to the air raids, and three and a half million homes were destroyed, while at the end of the war seven and a half million people were left homeless, and there were 31.1 cubic meters of rubble for every person in Cologne and 42.8 cubic meters for every inhabitant of Dresden. But we do not grasp what it all actually meant.

The ruin next door became Kiefer’s playground. Before the age of six, when his family moved, he would spend his days playing in the rubble, prising loose bricks to build ambitious structures. Hitler’s ruins have haunted his work. Rubble piles up relentlessly in Kiefer’s work, and he deliberately degrades his sculptures and paintings, as Richard Davey writes in an essay in the exhibition catalogue:

He allows nature and chemical reactions to take over the creative process. Paintings in process are burnt, slashed, buried or exposed to the elements. Canvases are laid on the ground to have paint and diluted acid poured on them, while works on lead are placed into electrolytic baths and left to stand and corrode.

These acts of artistic weathering were vividly revealed in the opening sequence of Alan Yentob’s Imagine film, in which we saw the artist hacking, scraping and chiselling into the encrusted surface of one of his paintings.

Unearthing the past that his country preferred should remain hidden was one of Kiefer’s first undertakings as an artist. In 1968-69, he was photographed in front of various European monuments and tourist sites performing the Nazi salute. Published in a handmade book entitled Occupations, the photographs created huge controversy, since they violated the unspoken postwar taboo on discussing the Nazi past or alluding to the mythic and spiritual imagery that the Nazis had appropriated. In the Imagine film, Kiefer makes a comment that challenges not just Germans, but all of us: ‘I do not know who I was in those times’. Elsewhere, he has remarked:

Something had accumulated in me that I wanted to bring out. I discovered that, without knowing it, I was impregnated by the times. My parents were not Nazis but they, too, were impregnated by these times. I wanted to know what I would have done if I had been 20 years older, so I put myself directly within the situation of those times.

Anself Kiefer, Ice and Blood, 1971

In the first gallery of the RA exhibition we encounter this ‘re-enactment of memory’, this challenge to the national desire for forgetting, in the form of Ice and Blood, a painting from 1971 in which Kiefer portrays himself in a field of bood-stained snow giving the Nazi salute.

Anselm Kiefer, Winter Landscape, 1970

A related painting from the same period, Winter Landscape, again depicts a frozen, barren landscape in which the ploughed earth is blanketed with snow, while spare trees in the background add to the bleakness of the work. A disembodied female head rises above the field, bleeding from the neck, and spots of blood-red watercolour tinge the pale ground. This depiction of a ruined terrain, dripping with blood, clearly evokes the horrors of World War II.

Anselm Kiefer, Your Golden Hair, Margarete, 1981

It was in the third room that I had to sit for a while, overwhelmed by the emotional force of the works displayed there; by their power and sheer scale. (The reproductions here, by the way, can give no sense of the scale and visceral force of these massive canvases, encrusted with layers of paint, ash, straw and other materials, which range from 12 to 18 feet in width and up to 10 feet in height.)

Here are two paintings – Margarete and Shulamith – inspired by Paul Celan’s poem ‘Death Fugue’. Poetry has had a powerful effect on Kiefer; he has spoken of poems being ‘like buoys in the sea. I swim to them, from one to the next: without them I am lost’. Beginning in 1980, and for some 25 years, Kiefer named canvases either Margarete or Sulamit, the two women named in Celan’s poem:

Black milk of daybreak we drink it at sundown

we drink it at noon in the morning we drink it at night

we drink it and drink it

we dig a grave in the breezes there one lies unconfined

A man lives in the house he plays with the serpents

he writes

he writes when dusk falls to Germany your golden hair Margarete

he writes it and steps out of doors and the stars are

flashing he whistles his pack out

he whistles his Jews out in earth has them dig for a

grave

he commands us strike up for the dance

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night

we drink you in the morning at noon we drink you at

sundown

we drink and we drink you

A man lives in the house he plays with the serpents

he writes

he writes when dusk falls to Germany your golden hair

Margarete

your ashen hair Sulamith we dig a grave in the breezes

there one lies unconfined

He calls out jab deeper into the earth you lot you

others sing now and play

he grabs at the iron in his belt he waves it his

eyes are blue

jab deper you lot with your spades you others play

on for the dance

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night

we drink you at at noon in the morning we drink you

at sundown

we drink and we drink you

a man lives in the house your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Sulamith he plays with the serpents

He calls out more sweetly play death death is a master

from Germany

he calls out more darkly now stroke your strings then

as smoke you will rise into air

then a grave you will have in the clouds there one

lies unconfined

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night

we drink you at noon death is a master from Germany

we drink you at sundown and in the morning we drink

and we drink you

death is a master from Germany his eyes are blue

he strikes you with leaden bullets his aim is true

a man lives in the house your golden hair Margarete

he sets his pack on to us he grants us a grave in

the air

He plays with the serpents and daydreams death is

a master from Germany

your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamith

– Death Fugue by Paul Celan, translated by Michael Hamburger

Anselm Kiefer, Sulamith, 1981 (click image to enlarge)

The Romanian poet Paul Celan was the only member of his family to survive incarceration in a concentration camp during the Holocaust. He committed suicide in 1970, at the age of 49, after producing a body of work that included ‘Death Fugue’, now a set text in German schools. Kiefer focusses on the two figures who are contrasted in the poem and act as its central metaphor: Margarete, with her cascade of blonde Aryan hair, and Shulamite, a Jewish woman whose black hair denotes her Semitic origins, but which is also ashen from burning.

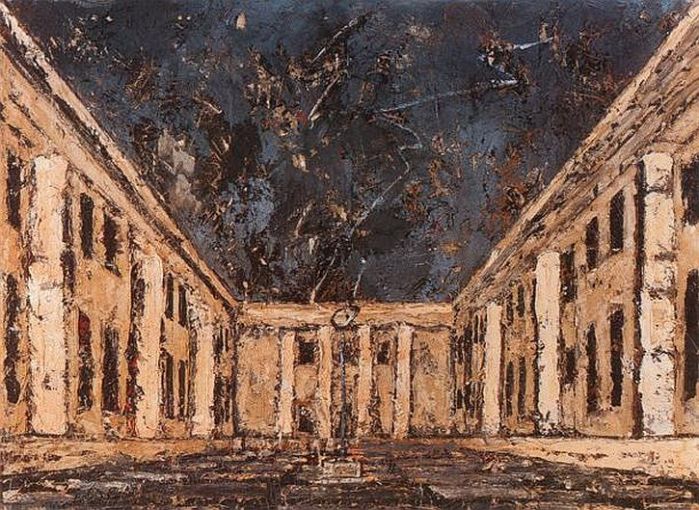

The late 1970s and 1980s saw Kiefer turn his attention to a further aspect of recent German history – the buildings of the Third Reich, designed by Albert Speer and Wilhelm Kreis to exalt the ideology of National Socialism. To the Unknown Painter (1983), Interior (1981) and Ash Flower (1983–97) are monumental paintings that originated with a photograph of architect Wilhelm Kreis’s Funeral Hall for the Great German Soldiers.

These are paintings on a huge scale that reinterpret the ruins of the monumental Neoclassical buildings commissioned by Hitler – reinterpret them as a memorial to the Holocaust. Crumbling and scorched by fire, the central aisle is occupied by a funeral pyre or the burnt stem of a sunflower.

Who is the unknown painter? In one interview, Kiefer noted that Hitler was himself a failed artist, three times rejected by art schools: ‘His was a story of misery and power’.

Anselm Kiefer, Interior, 1981 (click image to enlarge)

Anselm Kiefer, To the Unknown Painter, 1983

Ash Flower at the Anselm Kiefer retrospective (click image to enlarge)

Ash Flower, at nearly 26 feet wide, is the show’s largest painting, and is itself is a ruin. This massive painting, on which Kiefer worked for over fifteen years, features another Nazi ceremonial hall and gets its name from another poem by Celan poem, ‘I Am Alone’, which begins:

I am alone, I set the ashen flower

in a glass full of pure blackness.

A coating of ash and dirt give the surface of the painting a dull grey colour. At the centre, a large dried sunflower hangs upside down, spilling its dried seeds onto the ground. The ground is parched and cracked clay, a desert in which nothing can flourish.

Seated on the bench in the centre of this room, I turned to take in these monumental canvases that are profound and sorrowful with their allusions to Germany’s horrific recent past. I reflected that the last time I was here, in this room, was for the great Hockney exhibition in 2012, A Bigger Picture. A different day, a very different mood. British artists have not been confronted with the moral and philosophical questions with which Kiefer’s work has concerned itself.

Anselm Kiefer, The Paths of World Wisdom: Hermann’s Battle, 1980 (click to enlarge)

But it is not just Germany’s recent past with which Kiefer has been concerned. In works such as The Paths of Worldly Wisdom: Hermann’s Battle, Kiefer explores how aspects of German mythology and history contributed to the rise of Fascism. In the painting the faces of historical German figures are placed within the impenetrable forest of German folk memory and myth. Seemingly entangled in barbed wire, a funeral pyre burns at the painting’s centre.

For bourgeois Germans, the German forest provided a national landscape and a national myth (as Neil MacGregor pointed out in his recent radio series, Germany: Memories of a Nation, even today around 30% of the German landmass is covered by forest). Middle class Germans imagined their nation state as unified by a broad band of forests reaching from one end of the country to the other. The forest was the repository of powerful historical memories, stretching back into the mists of time – memories of the Teutonic past in which heroes such as Hermann had defeated the Romans on the Rhine and forged a national identity. The forests took on a special significance in the dark stories of the Brothers Grimm, in the Romanicism of Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings, or in the emotional relationship with nature of the Wandervögel movement. ‘Our stories begin in the forest,’ Kiefer has said, invoking not just the Nazi associations, but also his own beginnings when his family’s were forced to take refuge in the forest as the nation collapsed around them under an onslaught of Allied fire-bombing.

In The Paths of World Wisdom: Hermann’s Battle, the title alludes to Hermann who, by defeating the Romans, ensured that Germania remained independent from the Roman Empire. Hermann (whose image is depicted just above the flames of the central pyre) became a powerful symbol for 19th-century German nationalists, while during the Third Reich the Nazis used his myth to proclaim the racial superiority of the so-called ‘Aryan race’. The figures Kiefer has represented in the painting range from 18th- and 19th-century intellectuals, poets, and composers, to Prussian leaders and industrialists, to Nazi military leaders. The portraits were largely based upon those in a 1937 book which Kiefer discovered (he is an voracious reader and book collector), Face of the German Leader: 200 Portraits of German Fighters and Pioneers across 2000 Years, a text which provided a history that legitimated Nationalist Socialism.

Anselm Kiefer, Painting of the Scorched Earth, 1974

In Painting of the Scorched Earth (1974) the forest is a blackened and smouldering landscape, a blasted dead tree in the foreground and a ghostly palette superimposed. It suggests that the fires of war have laid waste the landscape in which 19th century Romantic painters found inspiration.

Anselm Kiefer, The Orders of the Night, 1996 (click image to enlarge)

In The Orders of the Night from 1996, Kiefer paints himself lying in a field of withered sunflowers (the flowers that grow in profusion in the region around Barjac in southern France where his studio was located at the time), gazing up at the bowed sunflower heads. Here is where we come to TS Eliot’s point about the meaning of a work lying somewhere between the artist and the person responding to it. The RA leaflet accompanying the exhibition explains that:

Sunflowers follow the sun, embodying the connection between the earhly and the celestial. They are equally emblematic of the cycle of birth-death-rebirth, and their seeds appear frequently in Kiefer’s works. He has said: ‘When I look at ripe, heavy sunflowers, bending to the ground with blackened seeds … I see the firmament and the stars.’

Kiefer’s statement is itself a reflection of his interest and wide reading in the fields of cosmology, ancient belief systems and arcane philosophies, since it echoes the writings of the 16th century astrologer, mathematician, cosmologist and Kabbalistic mystic Robert Fludd (to whom another painting in the exhibition is dedicated).

Do you need to know all this to be able to appreciate or derive personal meaning from the painting? Probably not – though it certainly helps.

Anselm Kiefer. For Paul Celan, Ash Flower, 2006

In another room, two vast canvases face each other, both made in response to poems by Paul Celan, and both featuring lead books. Kiefer regards lead as an important material. In 1985 he acquired the lead roof of Cologne cathedral when it was replaced, and has since incorporated the metal in his work. Kiefer believes that lead is the only material heavy enough to carry the bweight of human history. He believes that its properties most closely resemble ours:

It is in flux. It’s changeable. … Lead has always been a material for ideas. In alchemy, this metal stood on the lowest rung of the process of extracting gold. On the one hand, lead was bluntly heavy and connected to Saturn, the hideous man – and on the other hand it contains silver and was also already the proof of the other spiritual level.

These two paintings – For Paul Celan, Ash Flower and Black Flakes – both feature barren, snow-covered landscapes. In Celan’s poems, snow and ice often refer to the landscape of the Holocaust, symbolizing the oblivion and silence that descended over Europe at that time. facing one another were .

In Ash Flower a bleak landscape of snow and barren fields stretches to the horizon where there is a glimmer of light in the dark sky, just visible through bare trees. The words of the poem are written across the canvas upon which stand piles of burned books made from lead.

Anselm Kiefer, Black Flakes, 2006 (click image to enlarge)

Black Flakes offers the same bleak landscape, with snow-covered furrows, from which protrude stalks like cuneiform or Hebrew characters. Critics have seen the stalks as representing the barbed wire of the concentration camps. But they may also be a further reference to the German forest, and myths associated with trees and wood. The lead book, appearing carbonised, deliberately calls to mind Nazi book-burning, and Heinrich Heine’s prophecy: ‘Where they have burned books they will end in burning human beings’.

Black Flakes draws inspiration from a poem of the same name by Paul Celan, a German-speaking Romanian Jew who survived the concentration camps, though his parents did not. Celan’s father died of typhus and his mother was shot when exhausted and deemed unfit for work. One section of Celan’s poem reads: ‘Autumn bled all away, Mother, snow burned me through:/ I sought out my heart so it might weep, I found – oh the summer’s/breath,/it was like you.’ Words from the poem, written by Kiefer in charcoal, recede into the painting’s horizon line.

Snow has fallen, with no light. A month

has gone by now or two, since autumn in its monkish cowl

brought tidings my way, a leaf from Ukrainian slopes :”Remember it‘s wintry here too, for the thousandth time now

in the land where the broadest torrent flows :

Ya‘akov‘s heavenly blood, blessed by axes…

Oh ice of unearthly red – their hetman wades with all

his troop into darkening suns… Oh for a cloth, child,

to wrap myself when it‘s flashing with helmets,

when the rosy floe bursts, when snowdrifts sifts your father‘s

bones, hooves crushing

the Song of the Cedar…

A shawl, just a thin little shawl, so I keep

by my side, now you‘re learning to weep, this anguish,

this world that will never turn green, my child, for your child”!Autumn bled all away, Mother, snow burned me through :

I sought out my heart so it might weep, I found

– oh the summer‘s breath

it was like you.

Then came my tears. I wove the shawl.

Ages of the World at the RA

In a room on its own stands Ages of the World, an installation made specially for the RA. It consists of an enormous pile of canvases, rubble, meteorites, dead sunflowers and miscellaneous detritus, including bits of metal and what looks like discarded filmstrips. The canvasses are piled up as if ready for a bonfire, and you can’t help thinking of the Nazis book-burnings and their attacks on ‘degenerate’ art.

But on adjoining walls, Kiefer has placed monochrome gouaches that echo the sedimentary layers of the pile of canvases with the names of geological eras. So you slowly realise,as Rachel Cooke remarked in her Observer review, that the work ‘talks to the future as well as the past’. It is, perhaps about the unimaginable extent of geological time, the history of our planet’s evolution. According to the RA guide, the work is about the relationship between the human individual and the deep time of the cosmos, touching on ‘the great events of our planet, from the devastating impact of meteorites to the creation of fossil fuels, and hints at an ongoing pattern that will continue.’

The Morgenthau Plan, 2012: part of the RA display

In the penultimate room is another awe-inspiring display of massive canvases, a group of green-gold paintings, encrusted with metal, polystyrene, shellac, sheaves of wheat, paint layered over photographs, a shoe, and a pair of scales. This is the Morgenthau series, begun in 2012 and named after a leaked, but (obviously) never implemented American plan to de-industrialise Germany at the end of the war.

The title of the series refers to the Morgenthau Plan of 1944, proposed by the American Treasury Secretary, Henry Morgenthau Jr. His idea was to turn Germany into a pre-industrial, agricultural nation in order to limit her ability to wage wars in the future. In this clip from the Imagine film, we see Kiefer arranging the Morgenthau room at the RA and admitting that, having created these rather beautiful paintings of wheat fields and flowers, he thought they might appear ‘too comforting’ so he sought to give them another meaning by calling the series Morgenthau Plan. In an interview published in the Financial Times, Kiefer explained further:

I came to the title because I so much like flowers and I painted so many flower pictures that I had a very bad conscience, because nature is not inviolate, nature is not just itself. So what to do with this beauty? I thought, ‘I will call it Morgenthau’, in a cynical way telling that Germany would be so beautiful without industry. This way of turning it round, it tells you the ambiguity of beauty.

But does the meaning of this series just stop there, or is there something else going on here? At the end of Sophie Fiennes’ superb documentary about Kiefer’s working practices, the artist says: ‘The Bible constantly says everything will be destroyed – and grass will grow over your cities. I think that’s fantastic. And grass will grow here too’. That thought gives Fiennes the title of her film – Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow. Could it be that Kiefer – known to have a sense of the ephemeral nature of things – is thinking about the infinitesimal period of geological time in which humans have been on Earth and in which human activities have impacted on ecosystems (a period some geologists have named the anthropocene)? Is he imagining a time when, over the ruins of our cities, the grass will grow?

Anselm Kiefer, Morgenthau Plan, 2013 (click image to enlarge)

Anselm Kiefer, Morgenthau Plan, 2013 (click image to enlarge)

Anselm Kiefer, Morgenthau Plan, 2013

There can be little doubt that the Morgenthau landscapes owe something to Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows. But there’s something else here, edgy and sharp. In one of the pictures, L’Origine du Monde, a rock or meteorite is imprisoned inside a metal globe with vicious teeth that is suspended in front of the canvas. In the Observer, Rachel Cooke wrote:

A note on the wall urges the visitor to note the crows circling above, a symbol of death and resurrection. But it isn’t these flapping shadows that keep you in the room; it’s the whispering grass, the beatific sunshine, the splashes of cornflower blue. Kiefer is that most resolute of artists. He has never turned away from the difficult and the sombre; his career is a magnificent reproach to those who think art can’t deal with the big subjects, with history, memory and genocide. In the end, though, what stays with you is the feeling – overwhelming at times – that he is always making his way carefully towards the light.

Of all the things that I saw during our weekend in London, it is the Anself Kiefer exhibition which has haunted me since. Kiefer deals with big and important themes: history and memory; the horrors of the 20th century; the rubble and ash of war and the Holocaust. The rubble and ash of bricks, timber and mortar, but also the ash of human flesh. Forgetting is not permitted.

The RA video trailer for the exhibition

The late, lamented Robert Hughes talks about Kiefer

Sophie Fiennes’ film Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow

Since I first posted this link the complete film has been replaced by a trailer and an invitation to stream the complete film from Artificial Eye for £2.49.

See also

- Anselm’s alchemy: essay by Martin Gayford (RA Magazine, autumn 2014)

- How to read an Anselm Kiefer: an article by Sam Phillips (RA Magazine)

- Six recurring themes in the work of Anselm Kiefer (Time Out)

- Anselm Kiefer: The German artist looking history’s horrors in the eye (Independent)

- Anselm Kiefer review – remembrance amid the ruins (Observer)

Thanks so much for a fantastic post. I went to this exhibition a couple of days ago and was bowled over. We have seen Kieffer here and there over the years and always been impressed but this exhibition really gives you a fantastic overview, a real sense of his vision and beliefs and a truly aesthetic, emotional and intellectual experience. True art!

Thank you very much. I’m glad you enjoyed the post. Like you, I had seen the occasional Kiefer here and there, but I never expected to be as I was by this haunting exhibition.

Very thoughtful and compelling post. Thanks for it.

Thank you for posting this thoughtful piece, and especially for posting the magnificent Sophie Fiennes film. All that and the broadcast the other week of the Imagine film make up a little for living too far from London to get to the exhibition.

The quote from Sophie Fiennes in your first para reminds me of the small Celan poem ‘Die Posaunenstelle’ which in the translation by John Felstiner (Norton pbk 2001, p.366) reads:

The Shofar place

deep in the glowing

text-void,

at torch-height,

in the timehole:

hear deep in

with your mouth.

So much in those few words, the sound that is sounded when there are no words left, his function as a poet and how to read his work?

Thanks Angela – I’m pleased that you appreciated the post and enjoyed the Sophie Fiennes film. I must explore Celan in more depth. As to your closing question – a certain Glyn Luke writes preceptively on Amazon (reviewing the Felstiner book you reference):

The first stanza of Paul Celan`s poem Ice, Eden is as follows:

There is a land called Lost,

a moon grows in its reeds,

and with us, numbed by frost,

there`s something glows and sees.

The next two lines:

It sees, for it has eyes,

each eye an earth that`s bright.

It is one of the generous number of poems by this unique poet in John Felstiner`s selection, and it seems to hover somewhere just above the reader, like so many of Celan`s poems, as if longing to be understood yet refusing to yield up any meaning too facile or unequivocal. Celan was one of the most esoteric of poets, but never so oblique as to be opaque. His poems are too filled with a reserved passion, a tortured compassion, to deserve to be thought of as simply `difficult`.

I think, perhaps, the best poems are those that ‘hover somewhere just above the reader’.

Thank you for that very good quote from the reviewer Glyn Luke – I didn’t know the poem, and following your quote back to Amazon reveals more good things both in that review and in several of the others on the same page.

I’m new to Celan’s work too, though I had tried to read some of it a few years ago.. but I went back to it after the ‘Imagine’ documentary, and spent a couple of days or so with both the Felstiner and the Hamburger editions. My German is nowhere near good enough to appreciate it without the translations, and having both plus the original yields mutually enriching and interacting understandings. It’s a good journey …