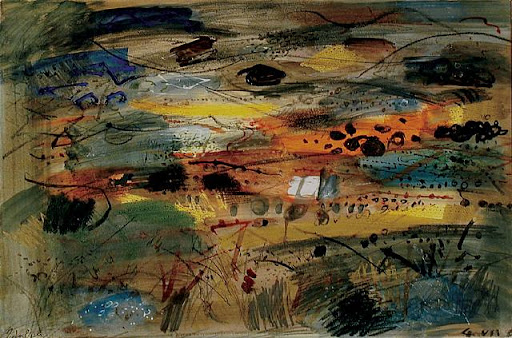

Graham Sutherland: Western Hills

A short break in Pembrokeshire set me off in search of painters whose work reflects the shapes and forms, the light and shade of the land. Like Cornwall, this corner of the British Isles has attracted many artists whose paintings have been inspired by the landscape of this county of craggy cliffs, golden sands and hidden valleys. Foremost among them are Graham Sutherland, John Piper and John Knapp-Fisher.

Although largely overlooked now, Graham Sutherland became one of the most famous artists in the world in the 1930s and 1940s, largely due to his passion for painting the Pembrokeshire landscape. Sutherland was born in London in 1903, but did not begin to paint in earnest until he was in his mid-30s, when, after visiting Pembrokeshire for the first time in 1935, he began painting landscapes that were inspired by the inherent strangeness of natural forms, with echoes of the visionary paintings of William Blake and Samuel Palmer, as well as his contemporary, Paul Nash.

The first one-man exhibition of his oil paintings, mainly Welsh landscapes, took place in 1938. During the Second World war, Sutherland was an Official War Artist, painting scenes of bomb devastation and of war work in mines and foundries. He was at the height of his international renown in the 1950s when he was commissioned to design the huge tapestry of Christ resurrected for Basil Spence’s new Coventry Cathedral.

Graham Sutherland was so moved by the Pembrokeshire landscape that he bequeathed a substantial collection of his work to the county in 1976, which for many years was exhibited in a dedicated gallery at Picton Castle. Then the gallery closed and for many years the collection languished unseen. Now, however, his works form a permanent part of the changing exhibitions at Oriel y Parc, the new gallery on the outskirts of St Davids.

Graham Sutherland: Pembrokeshire Landscape – Valley above Porthclais, 1935

When we visited the gallery this weekend, we found several works by Sutherland displayed as part of the current Stories from the Sea exhibition, including ‘Bird over Sand’ (1975) and ‘The Wave’, below. Sutherland once wrote about what brought him back, again and again, to this part of the country:

The quality of light here is magical and transforming. … Watching from the gloom as the sun’s rays strike the further bank, one has the sensation of the after-tranquility of an explosion of light. Or as if one has looked into the sun and had turned suddenly away. Herons gather. They fly majestically towards the sea.

Graham Sutherland, Bird over Sand, 1975

Graham Sutherland, The Wave

Another of Sutherland’s paintings on display currently is ‘Welsh Landscape With Roads’, painted at Porthclais in 1936, and on loan from the Tate.

Graham Sutherland, Welsh Landscape with Roads, 1936

The Tate’s note on this work states:

Sutherland wrote that such paintings expressed the ‘intellectual and emotional’ essence of a place. He conjures up a sense of the landscape’s ancient past through the inclusion of the animal skull and what may be standing stones in the distance. The unnaturalistic colouring, dramatic shaft of sunlight and minuscule fleeing figure create a threatening atmosphere. While the theme of a tiny man dwarfed by nature was common in eighteenth century painting, Sutherland’s transformation of the landscape into a eerie, primordial scene is distinctly modern.

Graham Sutherland, Estuary Trees and Rocks, watercolour

Graham Sutherland, Rocks on a beach, watercolour

Sutherland would wander around the coves on St Davids head with a little sketchbook in his hand, searching the seaweed and driftwood, looking for objects with interesting shapes: eroded rocks, tree-roots, a bleached skull, strange branches, rusty chains. All these details were isolated from their natural surroundings, and in his paintings and drawings were re-configured to express the emotions he experienced in the variety of forms seen in the landscape. The current exhibition at Oriel y Parc includes two watercolours from his Pembrokeshire sketchbooks (above).

Graham Sutherland, Road to Porthclais with setting sun

Sutherland was especially inspired by the topography around Porthclais, just south of St Davids. When he painted ‘Road at Porthclais with Setting Sun’ (above) he gave the motif of paths and sunken lanes wending through the fields a Palmer-like hallucinatory intensity: golden sun against black sky, darkness and brilliant light.

Graham Sutherland, Entrance to a Lane, 1943

There’s a similar intensity in ‘Entrance to a Lane’ (1939), above. Though apparently abstract, this painting represents a lane at Sandy Haven, in the south of the county. This painting is in the Tate collection, and their text for it reads:

By ‘paraphrasing’ what he observed, Sutherland felt he captured the essence of the landscape. This innovative technique fused the observational powers of John Constable with the daring of Pablo Picasso. The prominent black forms also reflect Sutherland’s debt to the landscape drawings of Samuel Palmer, whose work enjoyed a revival in the 1930s. This painting belongs to a tradition of images of wooded landscapes which seem to enfold the viewer. In 1939, with war looming, such a natural refuge may have had special significance.

John Piper: From St. Brides Towards St. Davids

The neo-romantic English painter John Piper also came to Pembrokeshire for the first time in the 1930s. The Oriel y Parc exhibition featured one of his paintings, ‘St Brides Bay’ (above). He first became acquainted with the landscapes of south Wales in 1937 when he married Myfanwy Evans. He made on the spot collages of Pembrokeshire beach scenes, and also became fascinated by Welsh architecture: the chapels, castles and ruins, which were to influence much of his later works. In 1963 he bought two abandoned cottages, with no electricity or phone, at the foot of Garn Fawr, the distinctive rock outcrop topped by an Iron Age fort that dominates Strumble Head. From here, he set out to explore the surrounding countryside, ‘trying to see what hasn’t been seen before’, as Welsh painter Kyffin Williams expressed it.

John Piper, Garn Fawr, 1962

John Piper: Garn Fawr 1979

John Piper: Garn Fawr on the road to south Pembrokeshire, 1980

John Piper, Garn Fawr near Strumble Head, 1962

Piper painted Garn Fawr many times, like Cezanne with Mont Ste Victoire, always finding a new way of revealing what he perceived. The cottage is still there.

John Piper’s cottage at Garn Faw

Like Sutherland, Piper paid homage to William Blake and Samuel Palmer; like him too, he was a war artist and contributed to the new Coventry cathedral (stained glass windows).

John Piper: Pembrokeshire landscape, 1962

The titles (of my work) are the names of places, meaning that there was an involvement there, at a special time: an experience affected by the weather, the season and the country, but above all concerned with the exact location and it’s spirit for me. The spread of moss on a wall, A pattern of vineyards or a perspective of hop-poles may be the peg, but it is not hop-poles or vineyards or church towers that these pictures are meant to be about, but the emotion generated by them at one moment in one special place’

– extract from European Topography by John Piper, 1969

John Piper: Pembrokeshire a distant prospect, 1964

John Piper: Coast of Pembroke, 1938

Louring clouds that belong to romantic painting hanging over a bare beach that might have been made for Courbet. At the edge of the sea, sand. Then, unwashed by the waves at low tide, grey-blue shingle against the warm brown sand: an intense contradiction in colour, in the same tone, on the same plane. Fringing this, dark seaweed, an irregular litter of it, with a jagged edge towards the sea broken here and there by washed-up objects; boxes, tins, waterlogged sand shoes, banana skins, starfish, cuttlefish, dead seagulls, sides of boxes with THIS SIDE UP on them, fragments of sea-chewed linoleum with a washed-out pattern. This line of magnificent wreckage vanishes out of sight in the distance, but it is a continous line that girdles England, and can be seen reappearing on the skyline in the other direction along this flat beach. Behind this rich and constricting belt against the sand dunes there is drier sand, sparser shingle, unwashed even at high tides, with dirty banana skins now and sides of boxes with the THIS SIDE UP almost unreadable. That, in whatever direction you look, is a subject worthy of contemporary painting. Pure abstraction is undernourished. It should at least be allowed to feed bare on a beach with tins and broken bottles.

– from Abstraction on the Beach, 1938

John Piper: Caerhedwyn Uchaf, Pembrokeshire, 1981

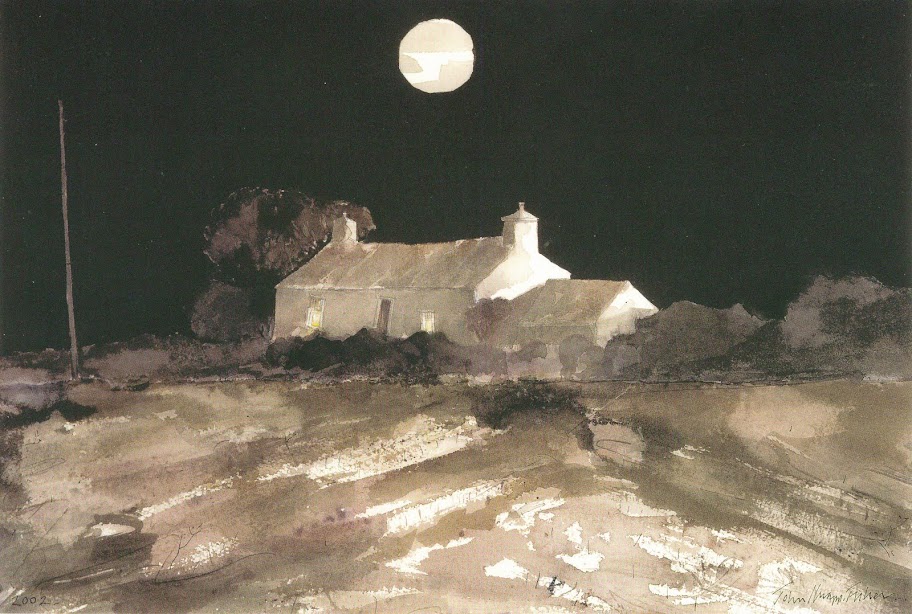

Our first encounter with the work of John Knapp-Fisher was when we came down to Pembrokeshire in the 1980s. We came back with postcard reproductions of his distinctive watercolour and ink paintings with their limited palette of earth colours and striking chiaroscuro, often depicting brightly-lit whitewashed buildings emerging from a dark background (below).

John Knapp-Fisher: Moon Over Watch, 2002

John Knapp-Fisher was born in 1931, studied Graphic Design at Maidstone College of Art from 1949, and later worked for the theatre as a designer and scenic artist. He moved to Pembrokeshire in 1965 and two years later opened his studio gallery in Croesgoch, a small village strung out along on the Fishguard to St Davids road.

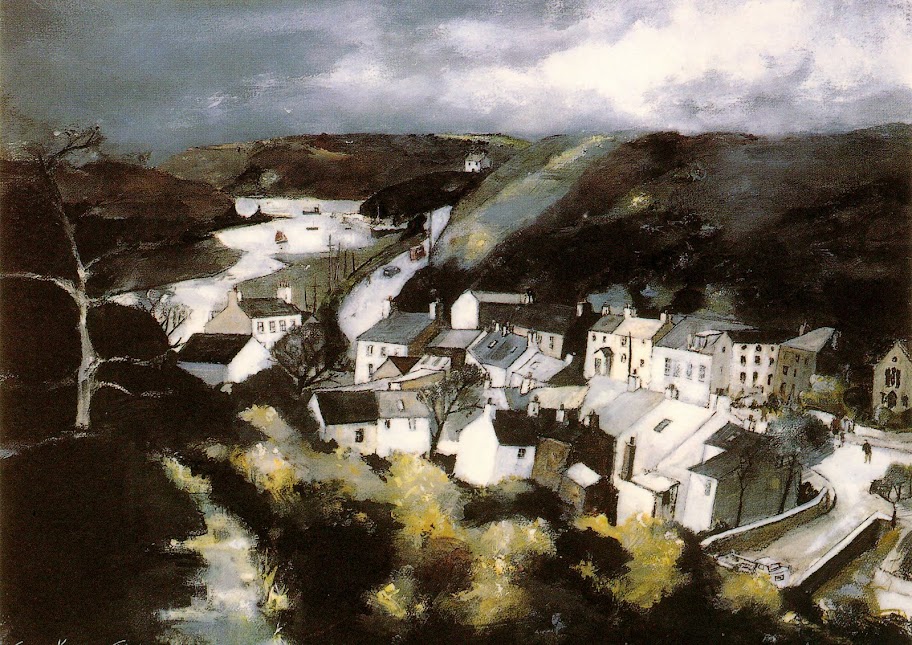

John Knapp-Fisher: Cresswell Street Tenby, 1998

Among the artists that Knapp-Fisher identifies as influences have been painters of the Cornishschool like Ben Nicholson and Alfred Wallis, as well as John Piper. In Cresswell Street, Tenby (above), the boat on the skyline seems to be a humourous nod to Wallis, as well as being a reflection of Knapp-Fisher’s lifelong love of boats and the sea (he has built them, sailed them and lived aboard one for several years).

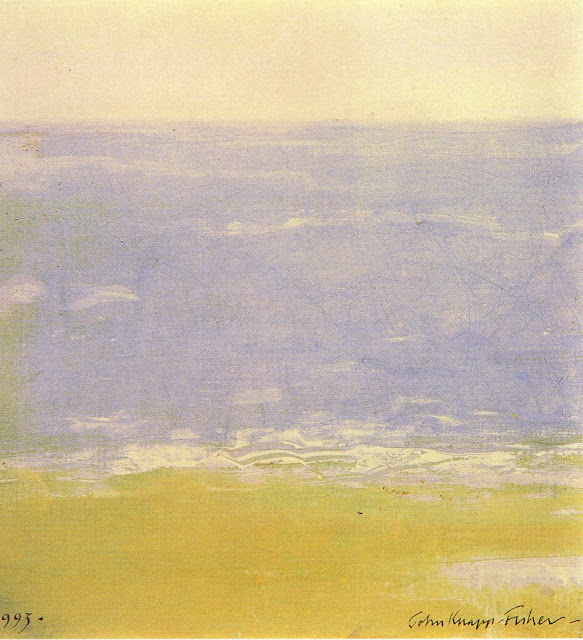

John Knapp Fisher: Solva, 1993

Knapp-Fisher’s name has become synonymous with Pembrokeshire landscape painting and his work is highly sought after by collectors in Britain and abroad. He has exhibited widely and is now, as he approaches his 80th birthday, one of Wales’ most popular and well-known artists.

John Knapp-Fisher: The Steps

Knapp-Fisher has written an excellent introduction to his work in his book, John Knapp-Fisher’s Pembrokeshire, republished in a revised edition in 2003. He writes straightforwardly, without pretension or pomposity, about his working methods and the things that inspire him:

With my work I tend to concentrate on small areas, often within walking distance of where I live. I will go out in all lights and weather making notes and sketches – sometimes finishing the picture (if in small format) on the spot.

John Knapp-Fisher: Trees and Water, 1989

John Knapp-Fisher: Hedgerow in the Back Lane, 1980

John Knapp-Fisher: Deraint’s Cottage

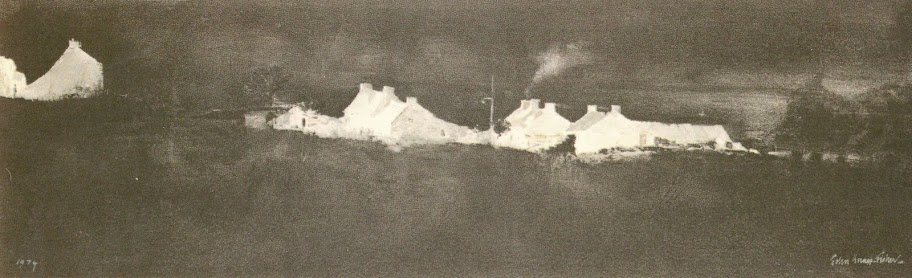

I am probably best known for ‘dark’ dramatic paintings with buildings catching the last rays of the sun against a stormy sky. … Most of the paintings in this oeuvre are inspired by day subjects of a light often seen on the north west Pembrokeshire peninsula. An example is ‘Abereiddy Evening’ (1974), below.

John Knapp-Fisher: Abereiddy, 1974

Most of John Knapp-Fisher’s early Pembrokeshire paintings were done with inks and watercolours, but recently he has turned more to oil, and utilised a wider colour palette, as in ‘Beach and Sky’ (1993) and ‘Sunset North Pembrokeshire Coast’ (1986), below.

John Knapp-Fisher: Beach and Sky, 1993

John Knapp-Fisher: Sunset North Pembrokeshire Coast, 1986

Anecdotal views – pretty ‘photographic’ subjects are of no interest to me. Pembrokeshire, like many other beautiful holiday areas, attracts artists who cater solely for the tourist industry. I believe in decentralisation. Why should London attract serious painters … while Pembrokeshire is relegated to a state of mediocrity? Distinguished painters have worked here in the past – Turner, Sutherrland, Piper, Richard Wilson, Augustus and Gwen John, and David Jones – as well as a significant number in the present, both young and old.

When we visited the Croesgoch gallery this week, there was an air of excitement as John Knapp-Fisher approaches his 80th birthday, with a major new exhibition in Cardiff this summer, and a TV documentary due to go out at the same time. His work continues:

I have worked at my art when my spirits have soared and when I have felt low and alone. I hope to continue to wander the paths and lanes, the seashores, farmyards and hills – sketchbook in hand.

John Knapp-Fisher outside his studio gallery at Croesgoch

Links

- Graham Sutherland: BBC profile

- National Museum Wales – Art Collections Online: Graham Sutherland

- Sutherland collection on the Tate website

- The art of John Piper: excellent website with galleries, articles and biography

- John Knapp-Fisher: personal website

- Oriel y Parc gallery St Davids

Thank you, Gerry. This is a stunning post. Although I’m familiar with the work of all three of the artists, it’s good to see the interconnections with the landscapes that inspire them. What John Piper is quoted as saying here is so true; so often the essence of a place isn’t captured in the whole panoramic view but in tiny details that perhaps others would consider inconsequential ephemera. I love Sutherland’s heron; it puts me in mind of something I wrote once…wonder if I’m brave enough to post it. x

Thanks for this fascinating post. I’ve discovered new artists and ways of seeing the landscape. I’d like to refer to your article in my student online learning log – hope it’s ok ?

You’re very welcome, Jane. I’m glad you enjoyed the post and found it useful. Good luck with your studies!