Berlin again. A little over a week after our return from Berlin, another coincidence: this time it’s a discussion about the life and significance of Frederick the Great on In Our Time this morning.

Frederick (the second one – there seem to have been at least eight Fredericks who ruled Prussia) became ruler in 1740 and dominated both Prussia and the European stage until his death in 1786.

During that time Frederick increased the power of the state, made Prussia the leading military power in Europe and put Berlin on the cultural map of Europe for the first time. An enigmatic figure, he was an absolute monarch who modelled his rule on the ideas of the Enlightenment, a prolific writer who attracted figures such as Voltaire to his court whilst expanding Prussian military power through wars in which led his military forces personally and had six horses shot from under him during battle. He fostered education, tolerance and great architecture, outlawed the death penalty and played the flute whilst being vilified for his militarism and ruthless partition of Poland.

The most beautiful surviving square in Berlin, the Gendarmenmarkt, reflects Frederick’s ambition to reshape Berlin along the lines of Paris – and his commitment to freedom of expression and religious tolerance. On one side of the square is the Opera House, first opened in 1742. Unlike his father, Frederick did not regard opera houses as places of the devil, and commissioned the architect Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff to build him ‘a Temple of Apollo’. In 1843 the building burned down to its foundations and in World War 2 it was destroyed by British bombing. On both occasions it was rebuilt to Knobelsdorff’s design.

Flanking the Opera House are two more reconstructed buildings which originated in Frederick’s design for the Gendarmenmarkt and reflect the fact that, though he was not religious himself, he was tolerant of the beliefs of others. At one end of the square stands the French Cathedral, designed as a haven for French Protestants seeking refuge in Berlin. At the time, French Huguenots, refugees from intolerance at home, made up about a quarter of Berlin’s population.

Facing the French Cathedral across the square is the Deutscher Dom, or German Cathedral, erected in 1708 for Calvinist and Lutheran worship during the reign of Frederick’s father, Frederick I, but substantially modified on Frederick’s instructions in 1785, when it was given its galleried dome (hence the name Dom). Another victim of Allied bombings, the church and tower burned down in 1943, and were restored between 1982 and 1996.

Nearby, on the Bebelplatz, is St. Hedwig’s Cathedral, a Roman Catholic cathedral Frederick permitted to be built in a fiercely Protestant land. In Potsdam, a stone’s throw from his Palace of Sanssouci, he loaned money for the construction of a Jewish synagogue (destroyed on Kristallnacht, 9 November 1938), remarking, ‘To oppress the Jews never brought prosperity on any government’.

Walking through the woods of the Grunewald on one of the days we were in Berlin, we stumbled upon the Grunewald Hunting Lodge, built by Frederick’s father in an idyllic location beside Grunewald lake. In warm sunshine we enjoyed coffee and cake at the cafe there. But, for Frederick this was probably a place where he endured misery and terror.

Before we travelled to Berlin, I had been reading Rory Maclean’s Berlin: Imagine a City, in which one chapter is devoted to astonishing story of Frederick’s upbringing:

The Soldier King’s three sons were to be raised as soldiers, awoken at dawn by cannon fire, trained in the fifty-four movements of the Prussian drill code. The first boy died at his christening when a crown was forced on his oversized head. The second child had life shocked out of him by the roar of guns fired too close to his cradle. The only surviving son was a thin and delicate rebel.

His father had created a formidable army and efficient civil service, but was otherwise a fanatic precursor of the Nazis, known to strike men in the face with his cane and kick women in the street, justifying his outbursts as religious righteousness.

As a child, Frederick was ordered by his father to rise at six, kneel by his bed and say a short prayer to God ‘loud enough for all present to hear’, and to dress and wash himself while taking breakfast in a quarter of an hour. His father could see no point in education, other than military training.

To toughen him up, the king knocked him about. He beat him for jumping off a bolting horse. He whipped him for wearing gloves in wet weather. One wild winter night, when the wind howled in from Russia and a pitcher of drinking water froze at the dinner table, he ordered him to stand guard outside the palace. The child took to hiding under his mother’s bed.

As he grew older, Frederick began to find other worlds through books He became passionately interested in French literature, poetry, philosophy, and Italian music. This enraged his father, who wanted to see his son follow more ‘masculine’ pursuits like hunting and riding.

At the age of sixteen Frederick found love with Hans Hermann von Katte, a young aristocrat who shared his love of French literature and music. The two young men became inseparable and hatched a plan to flee to England. The plan was betrayed, however, Frederick and Katte were arrested, and both were accused of treason.

At first Frederick’s father intended to have them both executed. In the end, Frederick was forced to watch the beheading of his friend Katte. When his companion appeared in the courtyard, Frederick called out from his cell, ‘My dear Katte, a thousand apologies,’ to which Katte replied, ‘My prince, there is nothing to apologize for.’

In 1740, when his father died, Frederick set about making Berlin a great city and a centre of ideas and music on a social, economic, intellectual and cultural par with France. Alexendra Richie writes in Berlin: Faust’s Metropolis:

He took the ideas of the French Enlightenment seriously, encouraging a free press and banning censorship, even if books or pamphlets were critical of him. At a time when people throughout Europe were being banished for stealing a loaf of bread, and long before Moliere complained that in Paris ‘they hang a man first, then try him afterwards’, Frederick abolished the torture of civilians and permitted the death sentence only for those convicted of murder. He was not religious but was tolerant of others’ beliefs, even allowing a Catholic cathedral in the city centre. He was obsessed with education, setting up training schools for teachers and making primary education mandatory.

For years he corresponded with Voltaire, who in the years before the French Revolution, believed only an enlightened monarch could bring social change to Europe. Rory Maclean observes that Voltaire’s ‘distrust of democracy’ pleased Frederick:

Voltaire invested his political hopes in Frederick, moving to the capital … dazzling Berlin’s dinner table conversation, debating questions of civil liberties late into the night.

But, as well as being an enlightened ruler, Frederick was also a ruthless despot. Through war and the First Partition of Poland in 1772, he turned the Kingdom of Prussia into a European great power. He believed that men of rank should be soldiers, thus establishing the equation between Prussian identity and militarism. Like Voltaire, he believed that the common man needed to be kept in his place, and was no supporter of democracy.

Alexandra Richie again:

Frederick’s extraordinary accomplishments touched only a tiny minority of Berliners. The city was still relatively poor and … the majority lived in poverty or squalor. … Above all, the military still dominated Berlin life: the barracks, parade grounds and uniforms prompted Goethe to write of his visit to Berlin in 1778 that its splendour … was obscured by ‘men, horses, wagons, guns, ammunition; the streets are full of them. If only I could describe adequately the monstrous piece of clock-work spread out here before one’s eyes.’

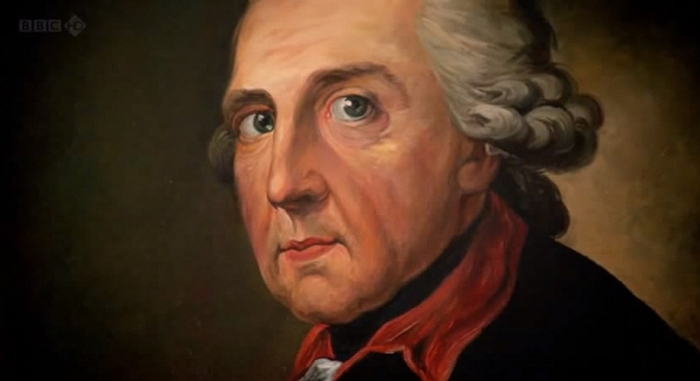

Frederick the Great remains an enigmatic and controversial figure in German history. 19th century German historians established Frederick’s reputation as the romantic model of a glorious warrior, praising his leadership, administrative efficiency, devotion to duty and success in raising Prussia to the rank of a leading power in Europe. He was glorified as a great German leader in the First World War, and then by the Nazis as a great precursor to Hitler (who had Anton Graff’s portrait on the wall of his underground bunker at the very end). Frederick’s reputation was long tarnished by the Nazi embrace of his wars of conquest and aggression. Since reunification, however, there has been something of a reassessment, with celebrations in 2012 honouring the 300th anniversary of his birth.

On that occasion Fritz Stern, professor at Columbia University and an expert on German history, remarked:

There are very few figures in Prussian or German history that are as difficult, as complex. There is no excuse for the aggression, but this is also a ruler who upon ascending to the throne immediately abolished torture in judicial proceedings. We could learn from that even today.

This BBC 4 documentary, Frederick the Great and the Enigma of Prussia, presented by Christopher Clark, considers his reputation as one of the greatest military leaders in modern European history, as a philosopher and cultured ‘Prince of the Enlightenment’ – and how his reputation was tarnished by association with Hitler’s Nazi regime.

Clark concludes that, in fact, Frederick wasn’t an enigma at all, echoing Alexandra Richie’s words in her Berlin history:

In reality, Frederick represented the end of an era: he was an absolute monarch who insisted on personal control of all aspects of life. He would remain one of the most important figures in the history of Berlin, but he did not understand the new force beginning to take hold even at the height of his reign. The Enlightenment ideas upon which he modelled his rule were also fuelling the rise of an independent, educated middle class which was no longer content to follow unquestioningly the dictates of the monarch.

Thanks for highlighting this deeper aspect of Frederick the Great, a momentous figure in the history of Europe.