The day begins to break, and soon there is the hum and noise of life. Those who have spent the night on doorsteps and cold stones crawl off to beg; they who have slept in beds come forth to their occupation, too, and business is astir.

– Master Humphrey’s Clock, p56

On my last day in London, and still pursuing the ghost of Charles Dickens through the streets of the capital, I decided to follow the Dickens walk ‘Heart of the City’ which is available as a podcast on The Guardian website.

First, though, I took myself to Wellington Street, off the Strand, where a blue plaque records that the weekly magazine Household Words, begun by Dickens in 1850 until 1859 and then continuing as All the Year Round had its office here. The ground floor is now occupied by the Charles Dickens Coffee House. Something told me it wasn’t worth going in.

North from here, at the southern fringe of Bloomsbury, once stood Dickens’ grandest London home, Tavistock House, its opulence testifying to Dickens’ status, popularity and success by the mid 19th century. But it is also only a short distance to Gower Street North, where as a child he had experienced poverty and shame as his father slipped into bankruptcy, forcing Charles to work in Warren’s Blacking Factory. That was situated just south of here, on Hungerford Stairs by the river, near the present Charing Cross railway station.

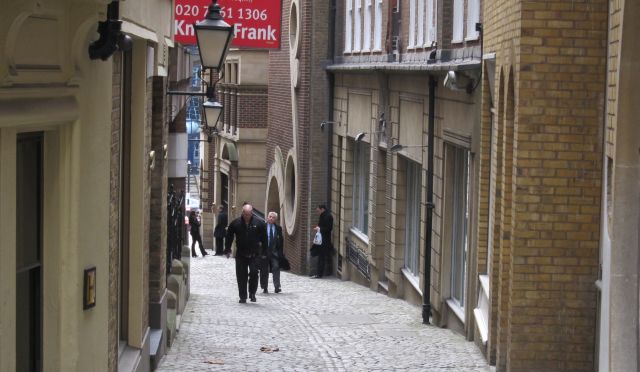

I took the tube to Monument. It was the first time I’d seen the 200 foot high column, designed by Christopher Wren, that marks the site on Pudding Lane where the Great Fire of London began in 1666 – that’s the disadvantage of always travelling around London on the underground. It towers above the alleyways just outside the tube station. Walking past Pudding Lane, I came to St Mary’s Hill, a narrow alley winding uphill away from the river.

The theme of the Guardian walk is the way in which Dickens saw the City of London change from being a place where people lived to one where people only worked, as it was gradually taken over by the banks, law firms and financial institutions. The walk began in Billingsgate at the church of St Mary at Hill which is squeezed into a small site surrounded by Victorian office buildings. There is a tiny churchyard with some gravestones – but no dead are buried here. Parliament outlawed new burials in the City of London in Dickens’ day, forcing the closure of its churchyards to new burials. It’s a symbol of of the way in which the City was turning into ‘a city of the dead, with the living just coming in to work’. As a child, Dickens experienced the City as a kind of village community; by the time he died, 80% of the population were gone, replaced by office blocks and warehouses.

When I think I deserve particularly well of myself, and have earned the right to enjoy a little treat, I stroll from Covent-garden into the City of London, after business-hours there, on a Saturday, or – better yet – on a Sunday, and roam about its deserted nooks and corners. It is necessary to the full enjoyment of these journeys that they should be made in summer-time, for then the retired spots that I love to haunt, are at their idlest and dullest. A gentle fall of rain is not objectionable, and a warm mist sets off my favourite retreats to decided advantage.

Among these, City Churchyards hold a high place. Such strange churchyards hide in the City of London; churchyards sometimes so entirely detached from churches, always so pressed upon by houses; so small, so rank, so silent, so forgotten, except by the few people who ever look down into them from their smoky windows. As I stand peeping in through the iron gates and rails, I can peel the rusty metal off, like bark from an old tree. The illegible tombstones are all lop-sided, the grave-mounds lost their shape in the rains of a hundred years ago, the Lombardy Poplar or Plane-Tree that was once a drysalter’s daughter and several common-councilmen, has withered like those worthies, and its departed leaves are dust beneath it. Contagion of slow ruin overhangs the place. The discoloured tiled roofs of the environing buildings stand so awry, that they can hardly be proof against any stress of weather. Old crazy stacks of chimneys seem to look down as they overhang, dubiously calculating how far they will have to fall. In an angle of the walls, what was once the tool-house of the grave-digger rots away, encrusted with toadstools. Pipes and spouts for carrying off the rain from the encompassing gables, broken or feloniously cut for old lead long ago, now let the rain drip and splash as it list, upon the weedy earth. Sometimes there is a rusty pump somewhere near, and, as I look in at the rails and meditate, I hear it working under an unknown hand with a creaking protest: as though the departed in the churchyard urged, ‘Let us lie here in peace; don’t suck us up and drink us!’

– The Uncommercial Traveller, chapter 23, ‘The City of the Absent’

Dickens was obsessed with the Thames. It runs through his novels, not only as a location but as a mood. As with the City, he saw the feelings and the use of the Thames change in his own lifetime. In his childhood, the nation’s war and commerce were conducted on sailing ships which couldn’t be directly unloaded onto the wharves because they were too big and bulky. So light cargo boats, called lighters and operated by lightermen, transferred goods to shore where they would would be loaded onto carts, or men’s backs.

The Company of Watermen was created by an Act of 1555 to regulate the services and charges of all watermen and wherrymen working between Gravesend and Windsor. The Act of 1555 also introduced apprenticeships for a term of one year for all boys wishing to learn the watermen’s trade. The present Watermen’s Hall dates from 1780 and remains the only original Georgian Hall in the City of London, and is a perfect example of eighteenth century domestic architecture.

He crossed by St Paul’s and went down, at a long angle, almost to the water’s edge, through some of the crooked and descending streets which lie (and lay more crookedly and closely then) between the river and Cheapside. Passing, now the mouldy hall of some obsolete Worshipful Company, now the illuminated windows of a Congregationless Church that seemed to be waiting for some adventurous Belzoni to dig it out and discover its history; passing silent warehouses and wharves, and here and there a narrow alley leading to the river, where a wretched little bill, FOUND DROWNED, was weeping on the wet wall; he came at last to the house he sought. An old brick house, so dingy as to be all but black, standing by itself within a gateway. Before it, a square court-yard where a shrub or two and a patch of grass were as rank (which is saying much) as the iron railings enclosing them were rusty; behind it, a jumble of roots. It was a double house, with long, narrow, heavily-framed windows. Many years ago, it had had it in its mind to slide down sideways; it had been propped up, however, and was leaning on some half-dozen gigantic crutches: which gymnasium for the neighbouring cats, weather-stained, smoke-blackened, and overgrown with weeds, appeared in these latter days to be no very sure reliance.

– Little Dorrit, chapter 3

Turning onto Eastcheap, the walker is directed to look over the entrance to the HSBC bank at the corner of Lovat Lane. There, on a building erected in the late 19th century, a freize of camels laden with goods records the fact that Eastcheap had once been where the headquarters of the East India Company were located.

They stood in the city streets upon a snowy Christmas morning … The poulterers’ shops were still half open, and the fruiterers’ were radiant in their glory. There were great, round, pot-bellied baskets of chestnuts, shaped like the waistcoats of jolly old gentlemen, lolling at the doors, and tumbling out into the street in their apoplectic opulence. There were ruddy, brown-faced, broad-girthed Spanish Friars, and winking from their shelves in wanton slyness at the girls as they went by, and glanced demurely at the hung-up mistletoe. There were pears and apples, clustered high in blooming pyramids; there were bunches of grapes, made, in the shopkeepers’ benevolence to dangle from conspicuous hooks, that people’s mouths might water gratis as they passed; there were piles of filberts, mossy and brown, recalling, in their fragrance, ancient walks among the woods, and pleasant shufflings ankle deep through withered leaves; there were Norfolk Biffins, squab and swarthy, setting off the yellow of the oranges and lemons, and, in the great compactness of their juicy persons, urgently entreating and beseeching to be carried home in paper bags and eaten after dinner. The very gold and silver fish, set forth among these choice fruits in a bowl, though members of a dull and stagnant-blooded race, appeared to know that there was something going on; and, to a fish, went gasping round and round their little world in slow and passionless excitement.

The Grocers’! Oh the Grocers’! Nearly closed, with perhaps two shutters down, or one; but through those gaps such glimpses. It was not alone that the scales descending on the counter made a merry sound, or that the twine and roller parted company so briskly, or that the canisters were rattled up and down like juggling tricks, or even that the blended scents of tea and coffee were so grateful to the nose, or even that the raisins were so plentiful and rare, the almonds so extremely white, the sticks of cinnamon so long and straight, the other spices so delicious, the candied fruits so caked and spotted with molten sugar as to make the coldest lookers-on feel faint and subsequently bilious. Nor was it that the figs were moist and pulpy, or that the French plums blushed in modest tartness from their highly-decorated boxes, or that everything was good to eat and in its Christmas dress; but the customers were all so hurried and so eager in the hopeful promise of the day, that they tumbled up against each other at the door, clashing their wicker baskets wildly, and left their purchases upon the counter, and came running back to fetch them, and committed hundreds of the like mistakes, in the best humour possible; while the Grocer and his people were so frank and fresh that the polished hearts with which they fastened their aprons behind might have been their own, worn outside for general inspection, and for Christmas daws to peck at if they chose.

– A Christmas Carol, Stave 3

The next stop was Leadenhall Market which dates back to the 14th century and which once specialised in meat, game and poultry (it also stands at what was the centre of Roman London). It ‘s still dedicated to eating, but now it’s a rather upmarket covered arcade hosting a variety of eating places for City office workers and tourists. Only one butcher remains (above), and above the windows of an eatery there are still the metal bars and hooks from which, I presume, hung game or haunches of meat (below).

Dickens, who had frequently gone hungry as a child, loved food and incorporated lavish details of meals in his novels. He loved Leadenhall Market as much as Covent Garden (which only dealt in fruit and flowers): to him it represented absolute abundance. It supplied all the eating houses of the City, the wealthy livery companies, the Mansion House with the very best of produce, including live game like ducks and geese. As Orwell wrote in his study of Dickens:

It is not merely a coincidence that Dickens never writes about agriculture and writes endlessly about food. He was a Cockney, and London is the centre of the earth in rather the same sense that the belly is the centre of the body. It is a city of consumers.

Up through a network of alleys I arrived in a small square, where, squashed into the top right corner is the thinnest pub I’ve ever seen – the George and Vulture Tavern, beloved of Mr Pickwick:

Mr. Pickwick resolved on immediately returning to London, with the view of becoming acquainted with the proceedings which had been taken against him, in the meantime, by Messrs. Dodson and Fogg. Acting upon this resolution with all the energy and decision of his character, he mounted to the back seat of the first coach which left Ipswich on the morning after the memorable occurrences detailed at length in the two preceding chapters; and accompanied by his three friends, and Mr. Samuel Weller, arrived in the metropolis, in perfect health and safety, the same evening.

Here the friends, for a short time, separated. Messrs. Tupman, Winkle, and Snodgrass repaired to their several homes to make such preparations as might be requisite for their forthcoming visit to Dingley Dell; and Mr. Pickwick and Sam took up their present abode in very good, old–fashioned, and comfortable quarters, to wit, the George and Vulture Tavern and Hotel, George Yard, Lombard Street.

Mr. Pickwick had dined, finished his second pint of particular port, pulled his silk handkerchief over his head, put his feet on the fender, and thrown himself back in an easy–chair, when the entrance of Mr. Weller with his carpet–bag, aroused him from his tranquil meditation.

‘Sam,’ said Mr. Pickwick. ‘Sir,’ said Mr. Weller.

‘I have just been thinking, Sam,’ said Mr. Pickwick, ‘that having left a good many things at Mrs. Bardell’s, in Goswell Street, I ought to arrange for taking them away, before I leave town again.’

‘Wery good, sir,’ replied Mr. Weller.

‘I could send them to Mr. Tupman’s, for the present, Sam,’ continued Mr. Pickwick, ‘but before we take them away, it is necessary that they should be looked up, and put together. I wish you would step up to Goswell Street, Sam, and arrange about it.’

‘At once, Sir?’ inquired Mr. Weller.

‘At once,’ replied Mr. Pickwick. […]

Mr. Pickwick drew the silk handkerchief once more over his head, And composed himself for a nap. Mr. Weller promptly walked forth, to execute his commission.

– The Pickwick Papers, chapter 26

It’s actually bigger than it looks – the entrance being on the left through the archway (above).

There has been a pub on this site since the 13th century, and the story of the building in the 19th century epitomises the changes that Dickens would have seen taking place. In the early 19th century it was the centre of a small village community at the heart of the City, but after that became something quite different. As the City emptied out, it was no longer a place where you were born and died, it was a city of men: in the new business institutions that took over the premises, there were no female employees; even the secretaries were male (though in Pickwick, the George and Vulture does have a pretty barmaid).

It still seemed to be the case today: as I meandered through the maze of narrow alleyways behind the pub, the clientale of nearby eateries and shops seemed to be mainly men.

Mr Dombey’s offices were in a court where there was an old-established stall of choice fruit at the corner: where perambulating merchants, of both sexes, offered for sale at any time between the hours of ten and five, slippers, pocket-books, sponges, dogs’ collars, and Windsor soap, and sometimes a pointer or an oil-painting.

The pointer always came that way, with a view to the Stock Exchange, where a sporting taste (originating generally in bets of new hats) is much in vogue. The other commodities were addressed to the general public; but they were never offered by the vendors to Mr. Dombey. When he appeared, the dealers in those wares fell off respectfully. The principal slipper and dogs’ collar man- who considered himself a public character, and whose portrait was screwed on to an artist’s door in Cheapside–threw up his forefinger to the brim of his hat as Mr. Dombey went by. The ticket-porter, if he were not absent on a job, always ran officiously before to open Mr. Dombey’s office door as wide as possible, and hold it open, with his hat off, while he entered.The clerks within were not a whit behind-hand in their demonstrations of respect. A solemn hush prevailed, as Mr. Dombey passed through the outer office. The wit of the Counting-House became in a moment as mute, as the row of leathern fire-buckets hanging up behind him. Such vapid and flat daylight as filtered through the ground-glass windows and skylight, leaving a black sediment upon the panes, showed the books and papers, and the figures bending over them, enveloped in a studious gloom, and as much abstracted in appearance, from the world without, as if they were assembled at the bottom of the sea; while a mouldy little strong room in the obscure perspective, where a shady lamp was always burning, might have represented the cavern of some ocean-monster, looking on with a red eye at these mysteries of the deep.

– Dombey and Son, chapter 13

Along past Cad the Dandy’s – Tailors and Shirtmakers I arrived in a small, dark courtyard overlooked by Simpson’s restaurant. It’s a place that would look recognisable, even now, to Dickens. His first job as a legal clerk was just outside the City, and both that and his second job as a reporter meant that he would have nipped through these lanes on errands almost on a daily basis. He would have noticed rapid changes taking place: these 18th century buildings at first would have been dwelling houses or taverns, but Dickens would have seen them turned into offices. People were moving out and clerks were moving in.

Pausing of a quiet Sunday … it is congenial to pass into the hushed resorts of business. Down the lanes I like to see the carts and waggons huddled together in repose, the cranes idle, and the warehouses shut. Pausing in the alleys behind the closed Banks of mighty Lombard-street, it gives one as good as a rich feeling to think of the broad counters with a rim along the edge, made for telling money out on, the scales for weighing precious metals, the ponderous ledgers, and, above all, the bright copper shovels for shovelling gold. When I draw money, it never seems so much money as when it is shovelled at me out of a bright copper shovel. I like to say, ‘In gold,’ and to see seven pounds musically pouring out of the shovel, like seventy; the Bank appearing to remark to me – I italicise appearing – ‘if you want more of this yellow earth, we keep it in barrows at your service.’To think of the banker’s clerk with his deft finger turning the crisp edges of the Hundred- Pound Notes he has taken in a fat roll out of a drawer, is again to hear the rustling of that delicious south-cash wind. ‘How will you have it?’ I once heard this usual question asked at a Bank Counter of an elderly female, habited in mourning and steeped in simplicity, who answered, open-eyed, crook-fingered, laughing with expectation, ‘Anyhow!’

Calling these things to mind as I stroll among the Banks, I wonder whether the other solitary Sunday man I pass, has designs upon the Banks. For the interest and mystery of the matter, I almost hope he may have, and that his confederate may be at this moment taking impressions of the keys of the iron closets in wax, and that a delightful robbery may be in course of transaction. About College-hill, Mark-lane, and so on towards the Tower, and Dockward, the deserted wine-merchants’ cellars are fine subjects for consideration; but the deserted money-cellars of the Bankers, and their plate-cellars, and their jewel-cellars, what subterranean regions of the Wonderful Lamp are these! And again: possibly some shoeless boy in rags, passed through this street yesterday, for whom it is reserved to be a Banker in the fulness of time, and to be surpassing rich. Such reverses have been, since the days of Whittington; and were, long before. I want to know whether the boy has any foreglittering of that glittering fortune now, when he treads these stones, hungry.

– The Uncommercial Traveller, chapter 23

The next stop was the Royal Exchange, a centre of trade and commerce for more than 400 years. It’s just across the road from the Bank of England and round the corner from where once stood South Sea House, home of the South Sea Company that until the 1850s managed the National Debt. This highlights something about Dickens’ attitude to money. His quarrel was not with wealth: his great quarrel was with debt, which had ruined his father’s life, and nearly ruined his own. What Dickens hated were usurers, those who charged interest on debt. He’d have had something to say about present circumstances.

The interior courtyard of the Royal Exchange is now an opulent grazing area for the monied drones of the banks and financial institutions of the streets around.

Strolling about the City as a lost child, I thought of the British Merchant and the Lord Mayor, and was full of reverence. Strolling about it now, I laugh at the sacred liveries of state, and get indignant with the corporation as one of the strongest practical jokes of the present day. What did I know then, about the multitude who are always being disappointed in the City ; who are always expecting to meet a party there, and to receive money there, and whose expectations are never fulfilled? What did I know then, about that wonderful person, the friend in the City, who is to do so many things for so many people; who is to get this one into a post at home, and that one into a post abroad; who is to settle with this man’s creditors, provide for that man’s son, and see that other man paid ; who is to ‘throw himself into this grand Joint-Stock certainty…

Had I ever learned to dread him as a shark, disregard him as a humbug, and know him for a myth ? Not I. Had I ever heard of him as associated with tightness in the money market, gloom in consols, the exportation of gold, or that rock ahead in everybody’s course, the bushel of wheat? Never. Had I the least idea what was meant by such terms as jobbery, rigging the market, cooking accounts, getting up a dividend, making things pleasant, and the like? Not the slightest.

– The Uncommercial Traveller

This was where I ended my walk, outside the Mansion House, built in 1752 as the first formal residence for the Lord Mayor of the City of London. Provoked by the sight of these imposing buildings, thinking of the financial power and political influence of the institutions within, and mindful of Dickens’ thoughts on debt, I decided to take a look at the Occupy London camp outside St Paul’s a block away.

‘How Do You Like London?’ Mr Podsnap now inquired from his station of host, as if he were administering something in the nature of a powder or potion to the deaf child; ‘London, Londres, London?’

The foreign gentleman admired it.

‘You find it Very Large?’ said Mr Podsnap, spaciously.

The foreign gentleman found it very large.

‘And Very Rich?’

The foreign gentleman found it, without doubt, enormement riche.

‘Enormously Rich, We say,’ returned Mr Podsnap, in a condescending manner. ‘Our English adverbs do Not terminate in Mong, and We Pronounce the “ch” as if there were a “t” before it. We say Ritch.’

‘Reetch,’ remarked the foreign gentleman.

‘And Do You Find, Sir,’ pursued Mr Podsnap, with dignity, ‘Many Evidences that Strike You, of our British Constitution in the Streets Of The World’s Metropolis, London, Londres, London?’

The foreign gentleman begged to be pardoned, but did not altogether understand.

‘The Constitution Britannique,’ Mr Podsnap explained, as if he were teaching in an infant school.’ We Say British, But You Say Britannique, You Know’ (forgivingly, as if that were not his fault). ‘The Constitution, Sir.’

The foreign gentleman said, ‘Mais, yees; I know eem.’

A youngish sallowish gentleman in spectacles, with a lumpy forehead, seated in a supplementary chair at a corner of the table, here caused a profound sensation by saying, in a raised voice, ‘ESKER,’ and then stopping dead.

‘Mais oui,’ said the foreign gentleman, turning towards him. ‘Est-ce que? Quoi donc?’

But the gentleman with the lumpy forehead having for the time delivered himself of all that he found behind his lumps, spake for the time no more.

‘I Was Inquiring,’ said Mr Podsnap, resuming the thread of his discourse, ‘Whether You Have Observed in our Streets as We should say, Upon our Pavvy as You would say, any Tokens -‘

The foreign gentleman, with patient courtesy entreated pardon; ‘But what was tokenz?’

‘Marks,’ said Mr Podsnap; ‘Signs, you know, Appearances- Traces.’

‘Ah! Of a Orse?’ inquired the foreign gentleman.

‘We call it Horse,’ said Mr Podsnap, with forbearance. ‘In England, Angleterre, England, We Aspirate the “H,” and We Say “Horse.” Only our Lower Classes Say “Orse!”‘

‘Pardon,’ said the foreign gentleman; ‘I am alwiz wrong!’

‘Our Language,’ said Mr Podsnap, with a gracious consciousness of being always right, ‘is Difficult. Ours is a Copious Language, and Trying to Strangers. I will not Pursue my Question.’

– Our Mutual Friend, chapter 11

Hello! We love the image of the butchers in Leadenhall and would like to feature this on our site. Please get in touch for more details – editorial.homemade@gravityroad.com. Thanks, Sandy