So far this in this series of posts celebrating the Bruegel room in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, I have looked at Bruegel’s paintings of the seasons and the works which share a preoccupation with religion, politics and war. In this final post I want to explore examples of the kind of work that resulted in the artist coming to be known, misleadingly, as ‘Peasant Bruegel’. Continue reading “Bruegel in Vienna, part 3: ‘Peasant’ Bruegel”

Tag: Vienna

Bruegel in Vienna, part 2: Religion, politics and war

In the first part of this appreciation of the Bruegel room in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, I looked at Bruegel’s paintings of the seasons. This time I want to explore a group of paintings that share a preoccupation with religion, politics and war. Continue reading “Bruegel in Vienna, part 2: Religion, politics and war”

Bruegel in Vienna, part 1: through the seasons

For true believers, the Bruegel room in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum must be the holy grail. Though paintings by the artist occupy two rooms in the Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels, they are interspersed with works by his two sons. But the room in Vienna is a concentrated showcase of the whole spectrum of Bruegel’s work: The Tower of Babel and The Procession to Calvary are major examples of works with a religious theme, while the three pictures from the seasons cycle illustrate Bruegel’s skill as a landscape painter. Then there are the depictions of everyday life portrayed in The Peasant Wedding and The Peasant Dance for which Bruegel is particularly renowned. Without question this was the high point of our pursuit of Bruegel across Europe. Continue reading “Bruegel in Vienna, part 1: through the seasons”

Two novels by Jenny Erpenbeck

This summer I’ve read two short, critically-acclaimed novels by Jenny Erpenbeck: Visitation, and The End of Days, winner of the Independent foreign fiction prize. I have to say that both books left me a little cold. Continue reading “Two novels by Jenny Erpenbeck”

Museum Hours: random details of the everyday

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along

– WH Auden, from Musee des Beaux Arts

For Jem Cohen, director of the excellent film Museum Hours which I have just seen, the film’s origins lay in his love of the paintings of Peter Bruegel the Elder and his sense that Bruegel’s paintings somehow echoed his own experience as a film-maker. The film is both a meditation on art and its meaning in everyday life, and the story of two strangers who meet and gradually become friends as autumn turns to winter in the streets of Vienna.

Johann is a guard at the Kunsthistorisches Art Museum where one day he encounters Anne, a Canadian who has come to Austria to be with her cousin who she hasn’t seen in years, who now lies in hospital in a coma. Anne (played by Mary Margaret OHara, the Canadian singer-songwriter known for her unique and unclassifiable 1988 album Miss America) knows no-one in the city and wanders its streets treating the museum as a refuge. Johann (played by Bobby Sommer) offers to help her, at first with directions to the hospital and then liaising with the hospital when language proves to be a barrier and obtaining for her a free museum pass. Gradually, they are drawn together as Johann joins Anne on hospital visits, and they explore the city, talking of their lives, and of paintings in the museum.

In his younger days, before he was employed as a museum guard, Johann had worked as a roadie and managed rock bands (Bobby Sommer here drawing on his own past). His observant, quietly-spoken narration lends the film its measured pace. At the hospital, at the bedside of Anne’s cousin, Johann describes from memory paintings that he has observed closely while performing his duties in the museum – works such as the self portrait by Rembrandt, painted in 1652 when the artist was beset by financial difficulties. He describes the paintings in loving detail, saying of a picture of Christ: ‘It’s the blueness of the river and skies, bluer than I could ever tell.’ As Johann speaks, Cohen cuts to a shot of a train moving silently beside a frozen river.

This is characteristic of a film which often turns away from the story of the two strangers (sometimes for as much as fifteen or twenty minutes) in order to meditate on looking and how we see the world – as reflected both in art and our daily lives. The camera moves constantly between details of canvases in the gallery out to the street – juxtaposing the faces of passers-by with portraits in the gallery, eggshells at the edges of a still life with cigarette stubs and a lost glove on the pavement. Cohen sees both as equally worthy of contemplation: the images on the museum walls and the quotidian swirl of passers-by and detritus on the street.

Museum Hours is far removed from a conventional Hollywood narrative: the lead characters are not young and glamorous stereotypes and their burgeoning friendship does not lead inevitably to sex. There is no neat resolution to the story of their encounter, and there is no sentimentality in the scenes at the hospital by the bedside of the comatose woman. Nevertheless, this elliptical study of two adults drawing comfort from a chance relationship is engaging – made even more so by the way in which Jem Cohen interweaves their story with his portrait of Vienna street life and a meditation on the way that life and art intertwine.

Looking is the central theme of Museum Hours. It is significant how often Cohen lets the gaze of his camera rest on eyes: eyes in paintings on the gallery walls, on city signs; eyes on sculptures, and the faces of passers-by in the city streets.

In the streets and public spaces of Vienna, Cohen’s camera notices details that we might pass by unseeingly: young boys on skateboards in a park, an old woman slowly climbing a hill, a stonemason’s carving in the walls of an ancient church, abandoned drink cans in the gutter, the faces of people muffled against the cold waiting at a bus stop, boarded-up shop windows, and the faces of individuals hopefully sifting and sorting through second-hand offerings at a street market.

Jem Cohen has spoken of how much of the inspiration for Museum Hours – the way in which he places his camera in public spaces to observe people and things and watch for the random – came from the Kunsthistorisches Museum’s celebrated gallery of paintings by Pieter Breugel, with their crowded compositions and attention to the haphazard details of everyday life. Cohen has shot many of his films in a documentary mode on the street, where, in his words, ‘there’s a kind of democracy of action, with random events and details all coexisting’. Looking at Bruegel’s paintings, Cohen writes,

I was particularly struck by the fact that the central focus, even the primary subject, was hard to pin down. This was clearly intentional, oddly modern (even radical), and for me, deeply resonant. One such painting, ostensibly depicting the conversion of St. Paul, has a little boy in it, standing beneath a tree, and I became somewhat obsessed with him. He has little or nothing to do with the religious subject at hand, but instead of being peripheral, one’s eye goes to him as much as to the saint. He’s as important as anything else in the frame. I recognized a connected sensibility I’d felt when shooting documentary street footage, which I’ve done for many years. On the street, if there even is such a thing as foreground and background, they’re constantly changing places. Anything can rise to prominence or suddenly disappear: light, the shape of a building, a couple arguing, a rainstorm, the sound of coughing, sparrows…

In the film’s pivotal scene, lasting some 20 minutes or so, an art historian (superbly acted by Ela Piplits) talks to a sceptical gallery tour party about the meaning and significance of Bruegel’s Conversion of St. Paul. Cohen scripted the lecture himself, and it clearly expresses his own deeply-felt responses to Bruegel’s paintings. The historian points out that, though ostensibly ‘about’ Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus, we also need to be mindful that he painted this work in 1567, just as the Catholic Duke of Alba was marching into the Netherlands at the head of an army of 10,000 men to suppress the Dutch Protestant revolt. Bruegel’s painting, she suggests, executed in a time of political repression was, like his work in general, radical, ‘more radical than they might seem.’

Saul – the figure in a blue doublet who has persecuted Christians – falls from his horse in a tiny detail shown in the painting’s middle distance. What we see at first glance, the lecturer argues, is a mass of foot soldiers and cavalry, dominated by a large horse’s arse. Bruegel, the lecturer continues, was radical for making ordinary people and everyday events valid subjects for artistic scrutiny. Though not himself a peasant, he dressed as a peasant to immerse himself in their culture. His paintings with their depiction of the small details of peasant life are ‘not sentimental, nor do they judge.’

She notes how, in Bruegel’s painting of a peasant wedding, many viewers are puzzled by the absence of the couple being married. She points out that the bride is the unobtrusive figure seated against the green curtain (the groom traditionally did not appear until later in the festivities). Jem Cohen, in an interview on Fandor has explained how Bruegel’s approach to painting a scene has echoed his own experience as a filmmaker, seeing the relationship to shooting in a documentary mode on the street, ‘where there’s a kind of democracy of action, with random events and details all coexisting’.

I get a big kick out of Bruegel. I’m not obsessed, but he’s amazing in many ways—his genuine interest in the actuality of peasant life, of street life in general, coupled with forays into the fantastic… Most of my work is grounded in the everyday, which can also be very strange, so I would hope we somehow share common ground. He decoupled landscape from being just the background for religious subjects, and compared with most of his contemporaries he pulled large-scale oil painting down to earth, into the world we all move through. I see him as a radical force, but also humble and funny. My relationship felt personal; I somehow felt he was a proto-documentary filmmaker.

In his Director’s Statement, published on the Museum Hours website, Cohen adds:

On the street, if there even is such a thing as foreground and background, they’re constantly changing places. Anything can rise to prominence or suddenly disappear: light, the shape of a building, a couple arguing, a rainstorm, the sound of coughing, sparrows… (And it isn’t limited to the physical. The street is also made up of history, folklore, politics, economics, and a thousand fragmented narratives).

In life, all of these elements are free to interweave, connect, and then go their separate ways. Films however, especially features, generally walk a much narrower, more predictable path. How then to make movies that don’t tell us just where to look and what to feel? How to make films that encourage viewers to make their own connections, to think strange thoughts, to be unsure of what happens next or even ‘what kind of movie this is’? How to focus equally on small details and big ideas, and to combine some of the immediacy and openness of documentary with characters and invented stories? These are the things I wanted to tangle with, using the museum as a kind of fulcrum.

In one of the most insightful reviews of Museum Hours, Michelle Aldredge writes on Gwarlingo:

Cohen suggests that it is not merely looking that matters, but presence–a type of looking that requires quiet and stillness and openness to the unexpected. Death is the common bond everyone shares. It is what allows us to draw a line from an Egyptian Pharaoh to a Dutch fox hunter to a tour guide in contemporary Vienna. It is presence that allows the boundaries of time and place to fall away. […]

As Johann sits with Anne by the cousin’s hospital bed and describes various artworks to the dying woman, the mere fact that Johann gives this dying stranger his time and attention imparts a certain dignity to her tragic situation. She is no longer dying alone in a hospital bed in Vienna with no friends or family to witness her passing. Impermanence is a constant, but that is no reason to withdraw, Cohen’s film seems to say.

Aldredge picks out a significant scene in Cohen’s film, in which Johann recalls a young ‘punk’ fresh out of university who had joined the museum staff and complained that the museum’s artworks were nothing more than trophies of the wealthy. He is unhappy that the museum charges admission, but Johann points out that he doesn’t object to paying admission to see a film. What is the difference?

With this simple scene, Cohen hints at a much larger topic—the commodification of culture. Without hitting us over the head with a message, he skilfully raises the question of audience and class. Is art only for the elite? What does it mean that Bruegel’s peasants are now ensconced inside of a great institution like the Kunsthistorisches? Shouldn’t artists be fairly compensated for their work? But when does compensation turn into commercialization? Who are artists working for? Themselves? Wealthy patrons? The general public? Is it right that an artist as great as Rembrandt should have so little money at the end of his life, as evidenced by his shabby clothes in a late self-portrait? And what stories do museums tell us? Can we really trust text panels and audio guides to tell us the whole story? For today’s youth, is the museum only a place to look at naked women and gore?

In an epilogue, Cohen leaves the gallery and presents us with a shot of an old woman making her way slowly and effortfully away from us up a steep city street until she is obscured by a building in the foreground. The image is framed in black, as if it is a landscape and she just a figure within it whose presence we might easily overlook.

Although I can appreciate that this slow-moving, episodic film might not be to everyone’s taste, I loved its intelligence and originality, greatly enhanced by the three central performances of Mary Margaret O’Hara, Bobby Sommer and Ela Piplits. O’Hara and Sommers apparently added a good deal of improvisation to their roles, making their characters appear truly authentic. If you are interested in art, especially Bruegel, and appreciate cinema that eschews stereotypical characters and conventional story arcs, this one’s for you.

Trailer

Jem Cohen’s Ground-Level Artistry

In this YouTube video essay, Kevin Lee compares Jem Cohen’s the punk-rock documentary Instrument with Museum Hours

See also

- In focus: Jem Cohen on Museum Hours (BFI)

- Jem Cohen: Memory and the Museum: interview in Fandor

The Hare With Amber Eyes

Objects have always been carried, sold, bartered, stolen, retrieved and lost. People have always given gifts. It is how you tell their stories that matters.

At primary school, I remember, we would be set a writing exercise such as, a day in the life of a penny. People would say of inanimate things that had been around for longer than a child could conceive of: ‘the stories they could tell!’ The Hare With Amber Eyes is a magnificent work of memory recovery – a family memoir, but also a voyage into the dark recesses of the twentieth century. Continue reading “The Hare With Amber Eyes”

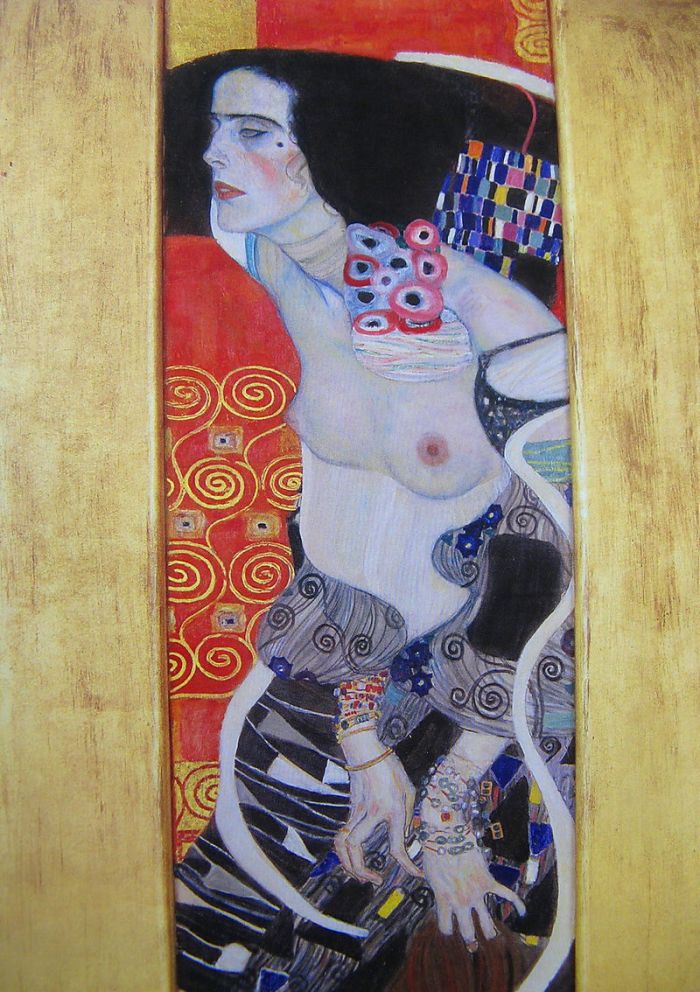

Klimt at the Tate

We’ve been to see the blockbuster exhibition, Gustav Klimt: Painting, Design and Modern Life in Vienna, at the Tate . As the Times review observes:

‘this is the first substantial exhibition of this most popularised of painters to come to this country. It’s certainly a coup for the European Capital of Culture. Klimt, after all, counts as an artistic A-lister. He is the icon-maker of our modern age. You only have to stand in front of one of his masterworks to know why. It’s not just the shimmering surface that entrances you: it’s the slow, languid pull of a deeper temptation. You slip into the clutches of his opulent confections, like his famous lovers into their luxurious embrace’.

However, exhibition doesn’t simply rely on visitors being stunned by the dazzle of Klimt’s paintings – it is also highly didactic, exploring Klimt’s role as the founder and leader of the Viennese Secession, a progressive group of artists and artisans. The work and philosophy of the Secession, embracing art, architecture, fashion, dazzling decorative objects and furniture, is presented in depth.

Major paintings and drawings from all stages of Klimt’s career are here alongside the work of Josef Hoffmann, the architect and designer and a close friend of the artist.

This is from the introduction to the exhibition:

Gustav Klimt: Painting, Design and Modern Life in Vienna 1900 explores the relationship between Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) as leader of the Viennese Secession and the products and philosophy of the Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workshop) – a highpoint of twentieth-century architecture and design.

Klimt played a critical role in the foundation, in 1897, and leadership of the Viennese Secession, a progressive group of artists and artisans driven by a desire for innovation and renewal. The philosophy of the Secession embraced not only art but also architecture and design that included the simple furniture and dazzling decorative art objects of the Wiener Werkstätte. They pursued the ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) aspiring to a synthesis of all the arts as championed by the composer Richard Wagner (1813 to 1883).

The architect and designer Josef Hoffmann (1870–1956), Klimt’s close friend and collaborator, and a co-founder of the Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte, created extravagant interiors for many of the painter’s most loyal patrons and collectors in their search for identity. Charting Klimt’s engagement with both the Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte, the exhibition therefore also presents a history of patronage and collecting in the cultural hothouse that was Vienna before the First World War.

Across two floors of the gallery, paintings and drawings by Klimt are shown in settings that approximate their original presentation as integral to the totally designed environment. Paintings are reunited with the furniture and design objects they originally accompanied. What emerges is a fascinating world of both luxurious opulence and refined simplicity.

On first entering the exhibition you encounter a striking reproduction of the Beethoven Freize (above), created by Gustav Klimt for the Fourteenth Exhibition of the Viennese Secession in 1902. Klimt’s Frieze was based on Wagner’s interpretation of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, celebrating humankind’s ‘struggle on the most magnificent level by the soul striving for joy’. It features gliding female figures symbolising ‘Longing for Happiness’. They are followed by Suffering Humanity, a naked kneeling couple and a standing girl. Suffering Humanity offer their pleas to the Knight in Shining Armour, who stands for the external driving forces. The reconstruction was created using the same techniques Klimt himself used, discovered as the original underwent restoration.

I admired the landscapes, including Pine Forest (above). It wasn’t until the late 1890s that Klimt turned to landscape subjects, during summer vacations spent in the picturesque Salzkammergut, outside the city of Salzburg. His landscapes are now a highly admired aspect of his work. A particular feature of the works is their standard size and square format. Klimt’s landscapes express his wider concerns with biological growth and the cycle of life. Their dazzling decorative surfaces and abstracted motifs align him with emergent modernist tendencies. The trees depicted in Pine Forest seem stylised, rendered in a strict vertical rhythm with reduced spatial depth.