We approached Forest, Field & Sky: Art out of Nature, last night’s documentary on BBC Four presented by Dr James Fox, with great anticipation since its subject was a form of art that has inspired us both – and provided the subject of many blog posts here. Fox didn’t disappoint, focussing on just a few brilliant examples of what is often labelled Land Art – art that is made directly in the landscape, from natural materials found in situ, such as rocks, tree branches or ice. Travelling across Britain, he discussed artists whose work explores our relationship to the natural world such as David Nash, Andy Goldsworthy, Richard Long, and James Turrell, in some cases watching the artist in the process of creating a new work. Continue reading “Forest, Field & Sky: Art out of Nature”

Tag: Richard Long

Uncommon Ground at Yorkshire Sculpture Park: ‘looking hard at real things’

After seeing the profound and meditative works by Ai Weiwei in the chapel at Yorkshire Sculpture Park last week, I spent some time looking at the current exhibition in the Longside Gallery there: Uncommon Ground: Land Art in Britain 1966 – 1979. Continue reading “Uncommon Ground at Yorkshire Sculpture Park: ‘looking hard at real things’”

John Piper: the shape and tilt of rocks

Our main purpose in popping over to Manchester last week was to see the John Piper exhibition at the Whitworth Gallery. Piper is an artist whose work I admire, but I have to admit that this exhibition – The Mountains of Wales – left me a little underwhelmed. Or maybe that should be overwhelmed? The Whitworth has brought together a large selection of paintings and drawings, all from a private collection, depicting mountains and rocks. The trouble is that, taken together, the note sung by these works is a dark monotone: predominantly greys, browns and blacks with occasional splashes of colour. As David Fraser Jenkins says in the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition, ‘Not one of the drawings looks as if it has been made on a sunny day.’ Continue reading “John Piper: the shape and tilt of rocks”

Making a beeline for Richard Long

Writing the other day about Rebecca Solnit’s history of walking, Wanderlust, I mentioned her discussion of the work of Richard Long, the land artist whose work has been dedicated to making ‘a new way of walking: walking as art’. He began in 1967 by making what was then a radically new kind of work, A Line Made by Walking,created by Long repeatedly walking a straight line in a field. Since then, he has continued to develop this idea, presenting the walks as art in three forms: maps, photographs, or text works. Each walk expresses a particular idea: so there have been walks in a straight line for a predetermined distance; walks between the sources of rivers; walks measured by tides, and walks delineated by stones dropped into a succession of rivers crossed.

Thinking about Long, I realised I had only a few days left to see the exhibition of his work that has been running all summer at the Hepworth gallery in Wakefield, with a linked exhibit at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. So, I set a course and made a beeline (quite literally as it turned out) for Yorkshire and Richard Long.

At the Yorkshire Sculpture Park I learned that the Richard Long exhibit had been located at the most distant point in the park. It seemed entirely appropriate that seeing an example of this artist’s work should require the effort of a modest walk. So follow me…

I set off down the hillside toward the lake. I love the YSP, the sense of space and varied landscapes in this vast expanse of rolling parkland, and the surprise of unexpected encounters with sculptures as you crest a rise, turn a corner or enter a glade. Currently there is a major exhibition of Joan Miro’s sculptures and other artworks, and the lawns are dotted with large bronze sculptures rarely seen outside his foundations in Barcelona and Palma de Mallorca, like Personnage, 1970 (below). Personally, I can take or leave Miro’s forms; I suppose I just don’t get them. It was interesting to browse the exhibits and read Miro’s comments on Catalan culture and art, rooted in his deep sense of national identity, in the month when the Catalan Parliament has voted to call a referendum on Catalan independence. But, like Laura Cummings in her review of last year’s Tate exhibition, Miro’s works don’t come across to me as political statements.

Walking on down the hillside I passed Jonathan Borofsky’s Molecule Man (below), aluminium gleaming in the sunlight that poured through the hundreds of holes in the sculpture that made it seem to float, light as air, giving form to the artist’s idea that the molecule structure of humans is composed of little more than water and air.

Further down, I found Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz’s monumental Ten Seated Figures, which, like most of her work, reflects her experience of war and political oppression. Abakanowicz was born in an aristocratic Polish-Russian family on her parent’s estate in Poland. The Second World war broke out when she was nine years old. The forces of Nazi Germany and then the Soviet Union swept through the land, followed by forty-five years of Soviet domination. In her work headless human figures often appear identical on the surface but on closer inspection reveal individuality, a commentary on societies which repress individual creativity in favour of collective goals and values:

My work comes from the experience of crowds, injustice and aggression…

By way of a complete contrast, near the Camellia House and in a wooded glade I encountered two works by Sophie Ryder, the artist who first drew us to the YSP many years ago with our young daughter. Crawling Lady Hare is a work behind after her exhibition here in 2008. Manus and the Running Dogs is a much earlier work from 1987, which shares a similarity – a group of animals running – to Crossing Place which we saw, again with our daughter, on the Forest of Dean sculpture trail in 1992. I love watching the faces – of children and adults alike – light up when they see a Ryder sculpture.

Emerging from the trees where leaves fell in all the colours of autumn – reds and yellows as bright as the Catalan colours of Miro’s painted sculptures back in the gallery – a cacophony of rooks or crows rose from the branches. It’s a sound that, for some inexplicable reason, always makes my heart soar.

Where the parkland slopes down to the lake, I mingled with Barbara Hepworth’s Family of Man: a group work from 1970 that consists of nine bronze upright abstract forms arranged across the sloping lawn. Each one is a simple, geometric shape, but Hepworth manages to imbue each figure with a distinctive personality. There are larger, more complex forms that seem to have distinctive male personalities, while smaller figures seem more timid, children perhaps, scared of speaking out of turn. This is a work that is best experienced outdoors, and the YSP have positioned it superbly here. As Hepworth once said:

All my sculpture comes out of landscape. No sculpture really lives until it goes back into landscape.

Down by the lake I saw a shed with a large reflective globe perched upon the roof . Now, I’ve built two sheds this year on our allotment, so I was intrigued. It turned out to be a recent work, Spiegelei, by Jem Finer, first made for the Tatton Park Biennial in 2010 and now resited here. According to the YSP’s interpretation:

‘visitors are invited into Spiegelei to experience a shift in reality, in which the world becomes inverted and sounds distorted, allowing a new and wonderful perspective on the familiar landscape of the Bretton Estate. This has been achieved through the construction of a 360-degree camera obscura using three lenses housed inside a sphere, angled to take full advantage of the views.

None of that worked for me, yet on a trip to Kent some time ago I enjoyed his Score for a Hole in the Ground, located in a wood in the Stour Valley. A seven metre high steel horn, like an old-fashioned gramophone, generates sound through rainfall. And I have been captivated by the idea of his Artangel commission Longplayer, a 1000-year long musical composition the longest non-repeating piece of music ever composed – that has been playing continuously since the first moments of the millennium, performed by computers around the world.

Then it was into the wood that surround the Lower Lake, walking a line to Richard Long.

Following the trail through the wood, every now and then I’d notice an object dangling from a tree branch, looking something like a garden bird house. In fact, collectively they are an artwork that is also an ecological intervention. The Bee Library comprises a collection of twenty-four bee-related books selected by Alec Finlay that were initially on display in the YSP Centre during springtime. Once read, each book was made into a nest for wild or ‘solitary’ bees in the grounds of the YSP. Together the library now forms an installation on a walking route which I was now following around the Upper Lake. Constructed from a book, bamboo, wire-netting and water-proofing, each nest offers shelter for solitary bees, whose numbers are in steep decline. New nests will be added in other places, building a global bee library. The Bee Poems are a collection of texts composed from a close reading of the books, published online.

I walked on, looking for Richard Long. He has written:

A footpath is a place.

It also goes from place to place, from here to there, and back again.

Any place along it is a stopping place.

Its perceived length could depend on the speed of the traveller, or its steepness, or its difficulty.

Reversing direction does not reverse the travelling time.

A path can be followed, or crossed.

A path is practical; it takes the line of least resistance, or the easiest, or most direct, route.

Sometimes it can be the only line of access through an area.

Paths are shared by all who use them.

Each user could be on a different overall journey, and for a different reason.

A path is made by movement, by the accumulated footprints of its users.

Paths are maintained by repeated use, and would disappear without use.

The characteristics of a path depend upon the nature of the land, but the characteristics can be universal.

My path finally brought me to Red Slate Line, a 1986 work made by Richard Long from slate found at the border of Vermont and New York State, and relocated here at the YSP for the summer. One strand of Long’s work is making sculptures in the landscape that are made by rearranging rocks and sticks into lines and circles without relocating them from the scene (the work is photographed, just as Andy Goldsworthy does with those works he creates that last fleetingly before they are washed or blown away, melt or decay). Meanwhile, another branch of Richard Long’s work collects up rocks, sticks or other materials to lay out those lines, circles or labyrinths on the gallery floor. In both cases, though, the landscape and the walk through it remains the primary focus.

Red Slate Line belongs to the second category – a gallery piece, now set down in a woodland setting, the shards of red slate arranged like a path leading down to the water’s edge. Rebecca Solnit wrote that these lines and circles record Long’s walks in ‘a reductive geometry that evokes everything – cyclical and linear time, the finite and the infinite, roads and routines – and says nothing’ (by which she means that we, the viewers, are given very little information about the walk that inspired them:

In some ways, Long’s work resemble travel writing, but rather than tell us what he felt, what he ate, and other such details, his brief texts and uninhabited images leave most of the journey up to the viewer’s imagination .. to do a great deal of work, to interpret the ambiguous, imagine the unseen. It gives is not a walk nor even the representation of a walk, only the idea of a walk, and an evocation of its location (the map) or one of its views (the photograph). Formal and quantifiable aspects are emphasized: geometry, measurement, number, duration.

Before visiting the YSP, I had spent some time at the Hepworth Gallery, just 15 minutes drive away in Wakefield. There, a small exhibition of work by Richard Long is just drawing to a close. The exhibition presents Long as a key figure in the emergence of land art, but notes too, that Long was also associated with Arte Povera, which questioned the boundary between art and life through the use of everyday materials and spontaneous events.

Journeying from his home town of Bristol to London, whilst a student at Saint Martin’s School of Art, Long created A Line Made by Walking (1967, above) in a grass field in Wiltshire, by continually treading the same path. It’s now been acknowledged as a pioneering artwork, incorporating performance art, land art and sculpture. The work also introduced Long’s intention to consider walking as art, exploring relationships between time, distance, geography and measurement. Long developed this intention throughout the 1970s and 1980s, making works in increasingly challenging and remote terrains and documenting the walks as texts, maps and photographs, such as Walking a Line in Peru (1972) and Sahara Line (1988). An important aspect of these works is the evidence of human activity that Long leaves as he walks, the trace of an encounter that is at the centre of the artist’s practice:

In the nature of things:

Art about mobility, lightness and freedom.

Simple creative acts of walking and marking

about place, locality, time, distance and

measurement.

Works using raw materials and my human

scale in the reality of landscapes.

Long’s sculptures occur either in the landscape, made along the way on a walk, or in the gallery, made as a response to a particular place. He works with natural materials such as sticks or slate to make sculptures and often uses mud or clay in his drawings and wall-works. This exhibition contains works from across Long’s career. It includes early photographs of his sculptures in the landscape such as Line Made By Walking and England 1968 where two paths cross in a field full of daisies.

The works in this exhibition, although made at different points in Long’s career, reflect the consistency of his approach, the same elements constant through the years:

My work has become a simple metaphor for life. A figure walking down his road, making his mark. It is an affirmation of my human scale and senses: how far I walk, what stones I pick up, my particular experiences. Nature has more effect on me than I on it. I am content with the vocabulary of universal and common means: walking, placing, stones, sticks, water, circles, lines, days, nights, roads.

– Richard Long,1983

Other photographed works on display include A Line in Japan – Mount Fuji (1979), A Circle in Alaska (1977), made of driftwood gathered on the Arctic Circle on the shore of the Bering Strait, and Circle in Africa (1978).

Circle in Africa depicts a circle made of burnt cactus branches on a rocky outcrop on Mulanje Mountain in Malawi. Long has explained how the circumstances in which Circle in Africa came about:

I was going to make a circle of stones on a high mountain in Malawi and then, when I got there, I couldn’t find any stones because there was no ice and snow to break the rock up. So I kept the idea of a circle and changed the material to burnt cacti which were lying around, that had been burnt in lightning storms. … I am an opportunist; I just take advantage of the places and situations I find myself in.

Alongside these photographs there is an annotated OS map of an area of the Cairngorms – Concentric Days, 1996 – with concentric circles superimposed, each representing a day and ‘a meandering walk within and to the edge of each circle’. You look and you imagine. There are two hand-made books – Nile (Pages of River Mud), 1990 and River Avon (1979) – both of which are assembled from papers dipped in the mud of those rivers.

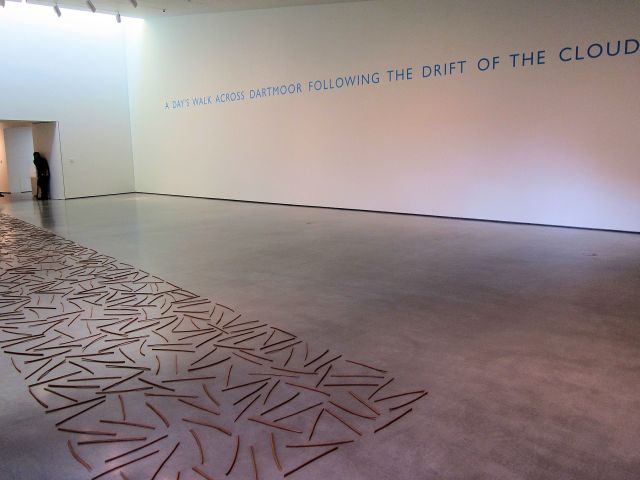

In an adjoining room are two contrasting pieces – Somerset Willow Line (1980) constructed from willow twigs arranged in a large rectangle across the gallery floor, and, spelt out in large capitals across the length of one wall, one of his text works: A DAYS WALK ACROSS DARTMOOR FOLLOWING THE DRIFT OF THE CLOUDS.

Another room brings together three more contrasting examples of Long’s work: Water Falls, a large piece like a painting created for this exhibition from paint overlain with scraped and scoured china clay, along with floor pieces, Cornish Slate Ellipse and Blaenau Festiniog Circle, constructed from blocks of Welsh slate in an arrangement that reminded me strongly of pieces exhibited by David Nash at the YSP last year.

I’ll finish with that other great walker, Robert Macfarlane. This is how he concluded an appreciation of Richard Long’s work he wrote for The Guardian:

I like his unpretentiousness. It’s probably what appeals to me most about Long and his work. He practises a kind of ritualised folk art. His circles, lines and crosses are radiantly symbolic, but also childishly simple; or, rather, they’re radiantly symbolic because they’re childishly simple. It’s for this reason that Long is ill-served by those interpreters who draw a cowl of Zennish mysticism over his sculptures, or who interpret his textworks (strings of words and phrases, often superimposed on to a photograph of the landscape that has been walked) as koan-like chants.[…]

No, Long is no magus. More of a high-end hobo. Among my favourite of his pieces is Walking Music, a textwork that records the songs that trundle through his mind as he walks 168 miles in six days across Ireland, the music keeping at bay the loneliness of the long-distance walker. Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Sinéad O’Connor singing “On Raglan Road”, Jimmie Rodgers’s “Waiting for a Train”, Róisín Dubh played on the pibroch …

Samuel Beckett – who, like Long, found much to meditate on and much to laugh at in the act of walking; and who, like Long, loved country lanes and bicycles, pebbles and circles – once observed that it is impossible to walk in a straight line, because of the curvature of the earth. There’s a great deal of Long in that remark. His art reminds us of the simple strangeness of the walked world, of the surprises and beauties that landscape can spring on the pedestrian. It’s good that Long is out there, knackering another pair of boots, singing Johnny Cash to himself as he walks the line.

See also

- Richard Long: artist’s website

- Richard Long slideshows: of sculptures, textworks and exhibitions (artist website)

- Walk the line: Robert Macfarlane on Richard Long (The Guardian)

- Richard Long interview: The Guardian

- Walking and Marking – The Art Of Richard Long: Caught By The River blog

- Richard Long: Walks on the wild side: critical assessment of Long’s work by the late Tom Lubbock (Independent)

Robert Macfarlane walks the South Downs

Eric Ravilious, Chalk Paths

Paths that cross

Will cross again

– Patti Smith

Another brilliant series of essays this week on Radio 3’s The Essay in which Robert Macfarlane, author of The Wild Places, reflected on paths, poetry and folk memories as he described walking the South Downs this summer, for 100 miles or so from Winchester southeastwards to the cliffs of Seven Sisters near Eastbourne, exploring its chalk paths and landscape.

Richard Long, Dusty Boots Line Sahara, 1988

‘Paths are the habit of a landscape. They are determined and sustained by usage, scored into the land by customary behaviour. They are acts of consensual making, and in this sense, quietly democratic’. In this respect, he contrasted the making of paths with the tracks of Richard Long (for example, in the Sahara, above), concluding that ‘you can’t make a path on your own’ and that his work ‘was to path what a snapped twig is to a tree. For path connects, almost always, with path; paths join, this is their duty. They relate places and, by extension, they relate people’. As evidence of this, he tells of meeting Lewis, who has been on the road for seven years, since the death of his wife, recording his walks in notebooks he posts back to his brother in Newcastle. ‘Somewhere near Amberley a barn owl lifted from a stand of phragmites reeds. We stopped to watch it hunt over the water margin, slowly moving north up the line of the river, a daytime ghost, as white as chalk, its wings beating with a huge soundlessness. ‘You go ahead’, said Lewis to me, ‘I’m in no hurry. I’m going nowhere, fast’.

Eric Ravilious, The Vale of the White Horse, 1939

With him as he walked, Macfarlane carried a book of the poems of Edward Thomas, whose work was deeply influenced by the landscape of the Downs, and he told of attempting to memorise his poem, Roads:

I love roads:

The goddesses that dwell

Far along invisible

Are my favourite gods.

Roads go on

While we forget, and are

Forgotten as a star

That shoots and is gone.

On this earth ’tis sure

We men have not made

Anything that doth fade

So soon, so long endure:

The hill road wet with rain

In the sun would not gleam

Like a winding stream

If we trod it not again.

They are lonely

While we sleep, lonelier

For lack of the traveller

Who is now a dream only.

From dawn’s twilight

And all the clouds like sheep

On the mountains of sleep

They wind into the night.

The next turn may reveal

Heaven: upon the crest

The close pine clump, at rest

And black, may Hell conceal.

Often footsore, never

Yet of the road I weary,

Though long and steep and dreary,

As it winds on forever.

Helen of the roads,

The mountain ways of Wales

And the Mabinogion tales

Is one of the true gods,

Abiding in the trees,

The threes and fours so wise,

The larger companies,

That by the roadside be,

And beneath the rafter

Else uninhabited

Excepting by the dead;

And it is her laughter

At morn and night I hear

When the thrush cock sings

Bright irrelevant things,

And when the chanticleer

Calls back to their own night

Troops that make loneliness

With their light footsteps’ press,

As Helen’s own are light.

Now all roads lead to France

And heavy is the tread

Of the living; but the dead

Returning lightly dance:

Whatever the road may bring

To me or take from me,

They keep me company

With their pattering,

Crowding the solitude

Of the loops over the downs,

Hushing the roar of towns

And their brief multitude.

Eric Ravilious, Wiltshire Landscape

On Macfarlane’s first night sleeping out in the open, the rain sluiced down. Edward Thomas returned often to the imagery of rain. Macfarlane mentioned his 1911 prose work, The Icknield Way, from which this passage comes:

I lay awake listening to the rain, and at first it was as pleasant to my ear and my mind as it had long been desired; but before I fell asleep it had become a majestic and finally a terrible thing, instead of a sweet sound and symbol. It was accusing and trying me and passing judgment. Long I lay still under the sentence, listening to the rain, and then at last listening to words which seemed to be spoken by a ghostly double beside me. He was muttering: The all-night rain puts out summer like a torch. In the heavy, black rain falling straight from invisible, dark sky to invisible, dark earth the heat of summer is annihilated, the splendour is dead, the summer is gone. The midnight rain buries it away where it has buried all sound but its own. I am alone in the dark still night, and my ear listens to the rain piping in the gutters and roaring softly in the trees of the world. Even so will the rain fall darkly upon the grass over the grave when my ears can hear it no more…

The summer is gone, and never can it return. There will never be any summer any more, and I am weary of everything… I am alone.

The truth is that the rain falls for ever and I am melting into it. Black and monotonously sounding is the midnight and solitude of the rain. In a little while or in an age – for it is all one – I shall know the full truth of the words I used to love, I knew not why, in my days of nature, in the days before the rain: ‘Blessed are the dead that the rain rains on.’

For 20 years, Thomas walked what he called ‘the long white roads’ and ‘frail tracks’ of England’s chalk country. Then in 1916, he enlisted and was sent as an officer to the chalk landscape of Arras in Northern France, with its far more dangerous paths. He was killed on Easter Monday, 1917. Not long before his death near Arras in 1916, Thomas wrote this:

Rain, midnight rain, nothing but the wild rain

On this bleak hut, and solitude, and me

Remembering again that I shall die

And neither hear the rain nor give it thanks

For washing me cleaner than I have been

Since I was born into this solitude.

Blessed are the dead that the rain rains upon:

But here I pray that none whom once I loved

Is dying tonight or lying still awake

Solitary, listening to the rain,

Either in pain or thus in sympathy

Helpless among the living and the dead,

Like a cold water among broken reeds,

Myriads of broken reeds all still and stiff,

Like me who have no love which this wild rain

Has not dissolved except the love of death,

If love it be towards what is perfect and

Cannot, the tempest tells me, disappoint.

– ‘Rain’, Edward Thomas, 7 January 1916

Eric Ravilious, Wilmington Giant

Macfarlane spoke of how Thomas developed a method of making one-day walks in the design of “a rough circle”, trusting that, as he put it in The South Country (1909), “by taking a series of turnings to the left or a series to the right, to take much beauty by surprise and to return at last to my starting-point”. On these walks, Thomas would follow what he called “the old ways”: the holloways, pilgrim paths and Neolithic-era chalk paths that seam the Downs. Thomas’s walks knowingly laid new tracks on an already marked ancient landscape.

Eric Ravilious, The Water Wheel

Walking from Bramber Bank to Kingston Down, in the company of writer Rod Mengham, Robert considered the Australian Aborigine concept of the songline, in which walking, wayfaring, singing and folk memory are aligned. On Edburton Hill they stopped to rest in a ‘kee-high wildflower meadow’, described vividly by Macfarlane:

‘We lounged under a clear sky within a dry, westerly wind. I knew only a few of the dozens of plant species that made up the meadow: agrimony, wild mignonette, red clover, yellow rattle, marjoram, knapweed, scabious, ladies bedstraw. It was a wild and chance-made garden; through it all wandered the string-like stem of the bindweed. Lying there, drowsy from the sun, the walk and the druggist’s scent of the flowers, with the flies weaving a gauzy mesh of sound above me, I began to imagine that, if I fell asleep the bindweed tendrils would lace around my limbs and fingers and I would wake like Gulliver in Liliput bound to the ground.’

Ravilious and his wife Tirzah working on a mural in 1933

In a brilliant and moving essay, Robert re-imagined the life of artist Eric Ravilious, who was fascinated by the ‘pure design’ of the South Downs – their paths, ridges and light. Ravilious’s passion for aerial landscapes eventually led him northwards, to Norway and Iceland. He disappeared off the coast of Iceland in September 1942 while on a rescue flight.

Ravilious…Downsman, follower of old paths and tracks, lover of whiteness and of light, and a visionary of the everyday…’The Downs’, he wrote once, ‘ shaped my whole outlook and way of painting because the colour of the landscape was so lovely and the design so beautifully obvious’. ..He made expeditions, slept out and walked for hours following the lines of the Downs, their ridges, rivers and tracks…From the late 1920s to the late 1930s Ravilious painted: deserted fields and Downland hillsides, abandoned farm machinery, waterwheels, fences – and paths. Paths fascinated him. He had read deeply in the work of Edward Thomas, revered the work of Samuel Palmer…He worked with a lightly loaded brush, allowing the white of the paper to show through, like chalk.

The paths of the Downs compelled Ravilious’s imagination; so did the light of the Downs, falling as white on green, and evoking ‘the strange downs magic’ of which Angus Wilson once spoke. The light of the Downs is distinctive for its radiance, possessing as it does the combined pearlescence of chalk, grass blades and a proximate sea. If you have walked on the Downs in high summer or high winter, you will know that Downs’ light also has a peculiar power to flatten out the view – to render scattered objects equidistant. This is the charismatic mirage of the Downs: phenomena appear arranged upon a single tilted plane, through which the paths burrow. In these respects the light of the Downs is kindred with another flattening light, the light of the polar regions, which usually falls at a slant and is similarly fine-grained. The light and the path: the flattening (the light) and the beckoning (the path). These are Ravilious’s signature combinations as an artist.

For most of Ravilious’s life, the Downs answered his landscape needs. Especially in winter – when the beech hangars stood out like ink strokes in a Chinese water-colour – they embodied his aesthetic ideal: crisp lines, the fall of pale light on pale land. But as the 1930s wore on, he began to desire an elsewhere, an otherworld. He located that elsewhere in the high latitudes of the far north – the envisioned land of the Arctic circle and the midnight sun. By the time the war began, he was restless to travel, hungry to swap chalk for ice, and south for north. His chance to do so came with his appointment in late 1939 as an official war artist, which gave him some control over his postings. In the last three years of his life, as Davidson has finely written, ‘the snow and the snow light on bare hills drew [Ravilious] steadily northwards’.

Eric Ravilious, Windmill, 1934

7 September 1942: at Castle Hedingham, a letter arrives for Tirzah from the Admiralty, signed HV Markham. ‘My lords desire me to express to you their deep sympathy in the great anxiety which this news must cause you…’. Tirzah stumbles over the grammar first time through. The next morning the postman brings a letter addressed in a familiar hand, and there is a momentary flare of hope. No, of course not. It is dated 1 September, and written in pencil. ‘We flew over the mountain country that looks like craters on the moon’, he tells her, ‘the shadows very dark and striped like leaves….’

Eric Ravilious, Downs in Winter, 1934

Walking the final miles of the South Downs with artist Chris Drury, Robert explores the sometimes eerie relationship between walking, collecting and creation. Drury was the part of the first generation of land artists that emerged in Britain. ‘I was drawn to Drury’s work’, says Macfarlane, ‘because of its preoccupation with paths and waymarkers, with cairns, shelters and objects found along the path. Drury’s best-known work, Medicine Wheel, was an 8-foot diameter wheel of bamboo, radiating from a central circle of straw-pulp paper.

Chris Drury, Medicine Wheel, 1982-3

Between the bamboo spokes were strung the objects that he had picked up while out walking each day for a year, from August to August: a sheep’s backbone, a little owl feather, a dead tiger moth on a thistle, a piece of petrel-blue flint, a bluebell seed-pod, a lapwing’s secondary, a crab’s claw. Hundreds and hundreds of found objects, sculpture functioning as almanac, calendar, wunderkammer, astrolabe’.

For years, said Macfarlane, Drury had also been experimenting with cairn sculptures and shelters. This reminded me that earlier this year, in Kent, we came across one of his shelters:

Chris Drury, Coppice Cloud Chamber

Links

- Robert Macfarlane on Richard Long (Guardian)

- Common Ground: essays by Robert Macfarlane in The Guardian

- Edward Thomas: Wikipedia

- Eric Ravilious: Wikipedia

- Chris Drury: his website

- Chris Drury: Heart of Reeds at Lewes

- The South Downs Way

- The South Downs Way: guide to walks and transport