…the great heart of London throbs in its Giant breast. Wealth and beggary, vice and virtue, guilt and innocence, repletion and the direst hunger, all treading on each other and crowding together, are gathered round it. Draw but a little circle above the clustering house-tops, and you shall have within its space, everything with its opposite extreme and contradiction, close beside.

– Charles Dickens, Master Humphrey’s Clock, 1841

Charles Dickens’ life and work is being celebrated in a major exhibition at the Museum of London on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the author’s birth. I went along expecting something rather dry – a few dusty objects and manuscripts that bore little relation to the excitement of reading a Dickens novel.

But I was wrong. This fascinating exhibition presents Dickens as the first great novelist of the modern city, showing how London was central to his works. It features rarely seen manuscripts of his novels including Great Expectations, David Copperfield and Bleak House but, using paintings, drawings and photographs of Victorian London, it also gives a vivid sense of what Dickens’s London looked like. And it culminates with a brilliant short film which links past to present, drawing on the fact that Dickens was an insomniac and used to pace the streets of London at night.

More than any other writer, Charles Dickens took us into the heart of the metropolis. He was fascinated by its complexity, movement and energy, and by lively chatter and accents of its people. He was an acute observer of the process by which London was becoming the world’s first modern city. His eyes took in everything: riches and squalor, the city’s extremes ofwealth and poverty. All of Dickens’ insight and energy is documented in this wonderful exhibition.

The exhibition is divided into ‘chapters’, looking at London as Dickens’ literary muse, Dickens’ home life and childhood, Victorian domestic life, Dickens’ involvement in the theatre, his fascination with the rapidity of economic progress and its consequences, and his continuing interest in criminal justice and social welfare.

Probably the most famous image of Dickens of all is Robert Buss’ unfinished posthumous painting Dickens’ Dream (pictured top), of the author in his chair, dreaming of his creations, who flutter in outline around his head. Buss has placed Dickens asleep in his study at Gad’s Hill Place, Higham, Kent. Despite being rejected by Dickens in 1836 as an illustrator of The Pickwick Papers, Buss began the work in homage to the author after his death in 1870. Buss in turn died in 1875, leaving the work unfinished, just as Dickens had failed to complete The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Scenes and characters from this novel feature prominently near Dickens and have been coloured in.

Next to the painting is the desk and chair at which he wrote and which Buss drew. At the Dickens Museum in Doughty Street I had seen the desk at which Dickens worked as a legal clerk. Here was another desk, the one he worked at in the years of success and high celebrity after he moved to Gad’s Hill Place in Kent in 1860. At this desk and seated in this chair, he wrote some of his most famous novels including Great Expectations and Our Mutual Friend. He kept to a regular daily routine. After breakfast at eight and checking that his house and grounds were in order, he would work in his study. He started by answering any pressing correspondence and then picked up where he had left off on his current novel or story. He would continue until lunchtime. In 2008, the chair and desk were given to Great Ormond Street Hospital to be auctioned to raise money. They were acquired by a private collector.

Another painting on display here is the iconic portrait, Charles Dickens in his Study (below), painted in 1859 by

William Powell Frith. It had been commissioned by John Forster, Dickens’ close friend and biographer. Frith felt that he had depicted a man ‘who had reached the topmost rung of a very high ladder, and was perfectly aware of his position’. Dickenswasn’t so sure, noting that ‘it is a little too much …as if my next door neighbour were my deadly foe, uninsured, and I had just received tidings of his house being afire’. The opening pages of the author’s latest work A Tale of Two Cities lie on his writing desk at Tavistock House, the grand home in London that Dickens owned at this time.

The variety and complexity of London fed Dickens’ imagination and creativity. He walked the streets, observing character and listening closely to sounds, especially overheard conversations. He was a master at distinguishing dialect, intonation and word pattern, a skill that made the voices of his characters ring true. The first section of the exhibition illustrates this through audio clips of accents and dialects that were familiar to the novelist, and with a display of evocative quotes that demonstrate Dickens’ powers of observation and characterisation:

Mr Chadband is a large yellow man, with a fat smile, and a general appearance of having a good deal of train oil in his system. Mrs Chadband is a stern, severe-looking, silent woman. Mr Chadband moves softly and cumbrously, not unlike a bear who has been taught to walk upright. He is very much embarrassed about the arms, as if they were inconvenient to him, and he wanted to grovel; is very much in a perspiration about the head; and never speaks without first putting up his great hand, as delivering a token to his hearers that he is going to edify them.

– Bleak House, chapter 19Quilp [was] an elderly man of remarkably hard features and forbidding aspect, and so low in stature as to be quite a dwarf, though his head and face were large enough for the body of a giant. His black eyes were restless, sly, and cunning; his mouth and chin, bristly with the stubble of a coarse hard beard; and his complexion was one of that kind which never looks clean or wholesome. But what added most to the grotesque expression of his face was a ghastly smile, which, appearing to be the mere result of habit and to have no connection with any mirthful or complacent feeling, constantly revealed the few discoloured fangs that were yet scattered in his mouth, and gave him the aspect of a panting dog. His dress consisted of a large high-crowned hat, a worn dark suit, a pair of capacious shoes, and a dirty white neckerchief sufficiently limp and crumpled to disclose the greater portion of his wiry throat. Such hair as he had was of a grizzled black, cut short and straight upon his temples, and hanging in a frowzy fringe about his ears. His hands, which were of a rough, coarse grain, were very dirty; his fingernails were crooked, long, and yellow.

– The Old Curiosity Shop, chapter 3As I came back, I saw Uriah Heep shutting up the office; and feeling friendly towards everybody, went in and spoke to him, and at parting, gave him my hand. But oh, what a clammy hand his was! as ghostly to the touch as to the sight! I rubbed mine afterwards, to warm it, and to rub his off. It was such an uncomfortable hand, that, when I went to my room, it was still cold and wet upon my memory.

– David Copperfield, chapter 15She was a fat old woman, this Mrs Gamp, with a husky voice and a moist eye, which she had a remarkable power of turning up, and only showing the white of it. Having very little neck, it cost her some trouble to look over herself, if one may say so, at those to whom she talked. She wore a very rusty black gown, rather the worse for snuff, and a shawl and bonnet to correspond. …. The face of Mrs Gamp—the nose in particular—was somewhat red and swollen, and it was difficult to enjoy her society without becoming conscious of a smell of spirits.

– Martin Chuzzlewit, chapter 19

This small etching is an example of a nugget easily overlooked here. It depicts a large heap of dust through which women are sifting in the hope of finding bits of metal or bone or anything else they can sell, and is an illustration from the first edition of Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor, published in 1851. It illustrates a theme that Dickens took up first in an essay:

These Dust-heaps are a wonderful compound of things. A banker’s cheque for a considerable sum was found in one of them. It was on Merries & Farquhar, in 1847. But bankers’ cheques, or gold and silver articles, are the least valuable of their ingredients. Among other things, a variety of useful chemicals are extracted. Their chief value, however, is for the making of bricks. The fine cinder-dust and ashes are used in the clay of the bricks, both for the red and gray stacks. Ashes are also used as fuel between the layers of the clump of bricks, which could not be burned in that position without them. The ashes burn away, and keep the bricks open. Enormous quantities are used. In the brickfields at Uxbridge, near the Drayton Station, one of the brickmakers alone will frequently contract for fifteen or sixteen thousand chaldrons of this cinder-dust, in one order. Fine coke, or coke-dust, affects the market at times as a rival; but fine coal, or coal-dust, never, because it would spoil the bricks.

– Charles Dickens, ‘Dust; or Ugliness Redeemed‘, Household Words, 13 July 1850

Later, in Our Mutual Friend, dust is a central metaphor and the prosperous dustman is an important character in the novel:

‘The man,’ Mortimer goes on, addressing Eugene, ‘whose name is Harmon, was only son of a tremendous old rascal who made his money by Dust.’

‘Red velveteens and a bell?’ the gloomy Eugene inquires.

‘And a ladder and basket if you like. By which means, or by others, he grew rich as a Dust Contractor, and lived in a hollow in a hilly country entirely composed of Dust. On his own small estate the growling old vagabond threw up his own mountain range, like an old volcano, and its geological formation was Dust. Coal-dust, vegetable-dust, bone-dust, crockery dust, rough dust and sifted dust,–all manner of Dust.’

Then there are images that show us places that Dickens frequented. This moonlight view of the Strand waterfront, ‘York Water Gate and the Adelphi from the River by Moonlight’, was painted around 1850 by Henry Pether. In the distance Somerset House, Waterloo Bridge, St. Brides spire and St. Pauls Cathedral can all be seen. In 1834, Dickens lodged for a brief period at 15 Buckingham Street, near the Adelphi. The pub also features in David Copperfield:

I was fond of wandering about the Adelphi, because it was a mysterious place, with those dark arches. I see myself emerging one evening from some of these arches, on a little public-house close to the river, with an open space before it, where some coal-heavers were dancing; to look at whom I sat down upon a bench.

–David Copperfield

The coaching inn is a location that crops up in many Dickens novels, and there is a suberb exhibit of photographs of typical coaching inns of Dickens’ London looking, with their galleries surrounding an enclosed courtyard, like caravanserais. This is the Oxford Arms, a 17th Century galleried inn that was demolished in 1876.

Coaching inns feature particularly in The Pickwick Papers, which has Samuel Pickwick and his fellow travellers tour southern England by coach:

There are in London several old inns, once the headquarters of celebrated coaches in the days when coaches performed their journeys in a graver and more solemn manner than they do in these times; but which have now degenerated into little more than the abiding and booking-places of country wagons. The reader would look in vain for any of these ancient hostelries, among the Golden Crosses and Bull and Mouths, which rear their stately fronts in the improved streets of London. If he would light upon any of these old places, he must direct his steps to the obscurer quarters of the town, and there in some secluded nooks he will find several, still standing with a kind of gloomy sturdiness, amidst the modern innovations which surround them.

– The Pickwick Papers, chapter 10

This is a contemporary view of Warren’s shoeblacking factory and warehouse at Hungerford Stairs where Dickens worked and which became the inspiration for Murdstone and Grinby’s in David Copperfield. The factory is described in the novel as ‘a crazy old house with a wharf of its own, abutting on the water when the tide was in, and on the mud when the tide was out, and literally overrun with rats’. This is how Dickens described it to his biographer, John Forster:

The blacking-warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river. There was a recess in it, in which I was to sit and work. My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking; first with a piece of oil-paper, and then with a piece of blue paper; to tie them round with a string; and then to clip the paper close and neat, all round, until it looked as smart as a pot of ointment from an apothecary’s shop. When a certain number of grosses of pots had attained this pitch of perfection, I was to paste on each a printed label, and then go on again with more pots. Two or three other boys were kept at similar duty down-stairs on similar wages. One of them came up, in a ragged apron and a paper cap, on the first Monday morning, to show me the trick of using the string and tying the knot. His name was Bob Fagin; and I took the liberty of using his name, long afterwards, in Oliver Twist.

– John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens

A view of Covent Garden Market in 1864, painted by Phoebus Levin, illustrates another location familiar to Dickens. He describes Covent Garden Market in ‘The Streets – Morning’, one of the short stories in the collection Sketches By Boz:

Covent-garden market, and the avenues leading to it, are thronged with carts of all sorts, sizes, and descriptions, from the heavy lumbering waggon, with its four stout horses, to the jingling costermonger’s cart, with its consumptive donkey. The pavement is already strewed with decayed cabbage-leaves, broken hay-bands, and all the indescribable litter of a vegetable market; men are shouting, carts backing, horses neighing, boys fighting, basket-women talking, piemen expatiating on the excellence of their pastry, and donkeys braying.

There’s a wonderful display of watercolour by George Scharf, an artist whose work was previously unknown to me. Scharf walked the London streets observing the amazing variety of street life in thousands of small drawings, just as Dickens described it in words:

Then, came straggling groups of labourers going to their work; then, men and women with fish-baskets on their heads; donkey-carts laden with vegetables; chaise-carts filled with live-stock or whole carcasses of meat; milk-women with pails; an unbroken concourse of people, trudging out with various supplies to the eastern suburbs of the town.’

– Oliver Twist

Another watercolour by George Scharf shows the view looking towards St Martin’s-in-the-Fields, in 1828. To the south of St Martin’s-in-the-Fields there was a warren of small alleys and lanes. The area was shortly to be cleared away as part of John Nash’s Strand improvements. The artist lived nearby in St Martin’s Lane, not far from Church Lane shown here. As a boy, Dickens frequented ‘pudding shops’ in the vicinity when he was working at the nearby blacking factory. He described one coffee-room in St Martin’s Lane where, ‘in a dismal reverie’, he would read the inscription on a glass panel backwards as ‘MOOR-EEFFOC’.

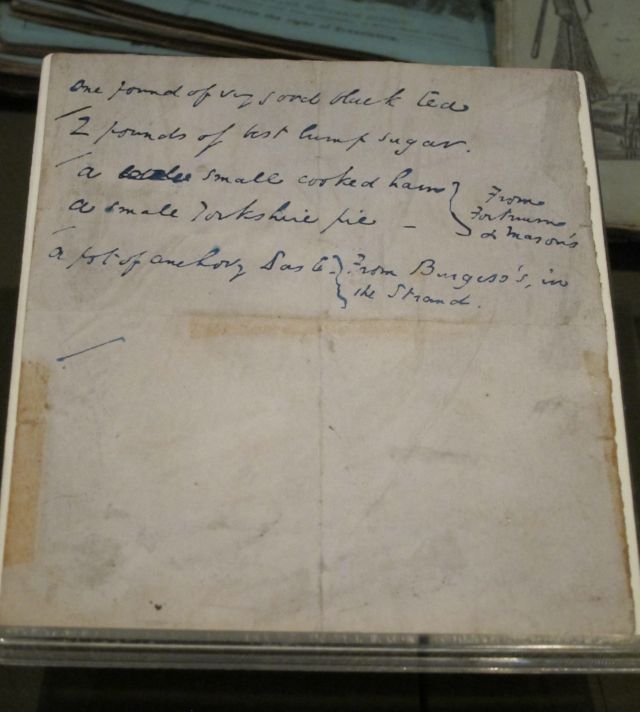

Another exhibit stands for the transformation in Dickens’ fortunes: a handwritten shopping list from around 1860 which Dickens wrote for his manservant, John Thompson. It includes a request for a cooked ham and Yorkshire pie from Fortnum and Mason in Piccadilly. The items were probably for Dickens’s private apartment on the third floor of 26 Wellington Street, above the offices of his periodical All the Year Round. Dickens’s favourite end to a meal was said to be

toasted cheese.

Dickens, you feel, would have loved the Internet. He felt that he was living in a special age of progress and improvement and called it ‘this summer-dawn of time’. He embraced new technology, crossing the Atlantic for his first reading tour of the United States on one of the first steamships, and travelling frequently by train, in contrast to his younger days when, as a young reporter, he journeyed slowly and in some discomfort around Britain by stagecoach. He was also an early adopter of the Penny Post, introduced in 1840, taking to writing and posting letters to friends, family and business contacts as a modern counterpart might text or email.

One of the ways in which this is illustrated in the exhibition is by means of a large and fascinating map showing the Telegraphic Lines of Europe in 1856. The map shows that the electric telegraph had reached the Crimea – as had Dickens’s work. In 1855, a battered copy of The Pickwick Papers in Russian was found at Sebastopol. In 1854 Dickens wrote to the Hon. Mrs Watson:

Few things that I saw, when I was away, took my fancy so much as the Electric Telegraph, piercing, like a sunbeam, right through the cruel old heart of the Coliseum at Rome. And on the summit of the Alps, among the eternal ice and snow, there it was still, with its posts sustained against the sweeping mountain Winds by clusters °£ great beams – to say nothing of it being at the bottom of the sea as we crossed the Channel.

Familiar as I was with Whistler’s Nocturnes, his moody evocations of the Thames at night, I had never before encountered his Thames Set until seeing them here in this exhibition. Between 1859 and 1860 Whistler produced a series of 16 etchings of the River Thames above and below London Bridge. Known as The Thames Set, the etchings capture the life of the working river and have an affinity with Dickens’ descriptions in novels such as Great Expectations and Our Mutual Friend:

Rogue Riderhood dwelt deep and dark in Limehouse Hole, among the riggers, and the mast, oar and block makers, and the boat-builders, and the sail-lofts, as in a kind of ship’s hold stored full of waterside characters, some no better than himself, some very much better, and none much worse.

Thames Police, 1859, is a view on the riverfront outside the Thames Police building at Wapping Wharf. Dickens had a number of Wapping and Limehouse connections – he used to visit his godfather Christopher Huffam at 5 Church Row.

This Whistler etching is entitled ‘Longshoremen’ and shows the interior of a tavern in Ratcliff. Dickens kept a small notebook where he jotted down ideas for novels and stories. One of his jottings was ‘A “long shore” man – woman – child – or family’. He linked this to another idea: ‘Found drowned. The descriptive bill upon the wall, by the waterside.‘ He further adds that this theme has already appeared in his work: ‘Done in Our Mutual [Friend]’. Both Dickens and Whistler were portraying the river’s working life at around the same time.

Also on display is this James Lawson Stewart watercolour, ‘Six Jolly Fellowship Porters public house’, dating to around 1885. This pub in Limehouse probably inspired the one in Our Mutual Friend, chapter 6

…a tavern of a dropsical appearance, had long settled down into a state of hale infirmity…but it had out-lasted, and clearly would yet outlast, many a better-trimmed building, many a sprucer public-house. Externally it was a narrow lopsided wooden jumble of corpulent windows heaped one upon another as you might heap as many toppling oranges, with a crazy wooden verandah impending over the water; but seemed to have got into the condition of a faint-hearted diver who has paused so long on the brink that he will never go in at all…The back of the establishment, though the cheif entrance was there, so contracted, that it merely represented in its connection with the front, the handle of a flat-iron set upright on its broadest end. This handle stood at the bottom of a wilderness of court and alley; which wilderness pressed so hard and close upon the Six Jolly Fellowship-Porters as to leave the hostelry not an inch of ground beyond its door.’

The offices of Dickens’s weekly magazines, Household Words and All the Year Round, were located off the Strand in Wellington Street. From the 1850s Dickens often stayed overnight in rooms above the offices and the area features in several of his novels. This painting, The Strand, Looking Eastwards from Exeter Change, is dated 1824 and is by Caleb Robert Stanley. The Strand is where Martin Chuzzlewit and the Nicklebys find lodgings. The painting looks east towards St Mary le Strand with St Clement Danes beyond.

Dickens never shied away from expressing his political opinions or bringing his own earlier experience of poverty into his work. His traumatic experience of working in a blacking factory after his father was confined to a debtors’ prison comes through strongly in the characters of Oliver Twist, Pip in Great Expectations, and, of course, his portrayal of the Dorrits in the Marshalsea debtors’ prison.

1869 saw the first appearance of The Graphic, an illustrated weekly edited by William Luson Thomas, a successful artist and social reformer. The Graphic had a very similar approach to Picture Post in the 20th century in that Thomas hoped that the images in the Graphic would result in social reform. One of the first artists taken on by Thomas was Samuel Luke Fildes who shared Thomas’ belief in the power of visual images to change public opinion on subjects such as poverty and injustice.

In the first edition of the Graphic newspaper that appeared in December 1869, Luke Fildes was asked to provide an illustration to accompany an article on the Houseless Poor Act, a new measure that allowed a certain quota of homeless people to be given shelter for the night in the casual ward of a workhouse. The picture produced by Fildes showed a line of homeless people applying for tickets to stay overnight in the workhouse. The engraving, entitled Houseless and Hungry, was seen by John Everett Millais who brought it to the attention of Dickens, who described the figures as ‘sphinxes against that dead wall’. He was so impressed that he immediately commissioned Fildes to illustrate The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

The queue for the casual ward continued to occupy Fildes mind, and he developed the composition for an oil painting which he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1874, and on display in this exhibition. The workhouse and the struggle for work and shelter, had been a preoccupation of Dickens throughout his writing career. In Dombey and Son, chapter 33, Harriet Carker’s thoughts are expressed in these words:

She often looked with compassion, at such a time, upon the stragglers who came wandering into London, by the great highway hard by, and who, footsore and weary, and gazing fearfully at the huge town before them, as if foreboding that their misery there would be but as a drop of water in the sea, or as a grain of sea-sand on the shore, went shrinking on, cowering before the angry weather, and looking as if the very elements rejected them. Day after day, such travellers crept past, but always, as she thought, In one direction—always towards the town. Swallowed up in one phase or other of its immensity, towards which they seemed impelled by a desperate fascination, they never returned. Food for the hospitals, the churchyards, the prisons, the river, fever, madness, vice, and death,—they passed on to the monster, roaring in the distance, and were lost.

In The Uncommercial Traveller in 1861, Dickens described a visit to Wapping Workhouse:

This was the only preparation for our entering ‘the Foul wards’. They were in an old building squeezed away in a corner of a paved yard, quite detached from the more modern and spacious main body of the workhouse. They were in a building most monstrously behind the time – a mere series of garrets or lofts, with every inconvenient and objectionable circumstance in their construction, and only accessible by steep and narrow staircases, infamously ill-adapted for the passage up-stairs of the sick or down-stairs of the dead.

A-bed in these miserable rooms, here on bedsteads, there (for a change, as I understood it) on the floor, were women in every stage of distress and disease. None but those who have attentively observed such scenes, can conceive the extraordinary variety of expression still latent under the general monotony and uniformity of colour, attitude, and condition. The form a little coiled up and turned away, as though it had turned its back on this world for ever; the uninterested face at once lead-coloured and yellow, looking passively upward from the pillow; the haggard mouth a little dropped, the hand outside the coverlet, so dull and indifferent, so light, and yet so heavy; these were on every pallet; but when I stopped beside a bed, and said ever so slight a word to the figure lying there, the ghost of the old character came into the face, and made the Foul ward as various as the fair world. No one appeared to care to live, but no one complained; all who could speak, said that as much was done for them as could be done there, that the attendance was kind and patient, that their suffering was very heavy, but they had nothing to ask for. The wretched rooms were as clean and sweet as it is possible for such rooms to be; they would become a pest-house in a single week, if they were ill-kept.

Now, I reasoned with myself, as I made my journey home again, concerning those Foul wards. They ought not to exist; no person of common decency and humanity can see them and doubt it. But what is this Union to do? The necessary alteration would cost several thousands of pounds; it has already to support three workhouses; its inhabitants work hard for their bare lives, and are already rated for the relief of the Poor to the utmost extent of reasonable endurance. One poor parish in this very Union is rated to the amount of five and sixpence in the pound, at the very same time when the rich parish of Saint George’s, Hanover Square, is rated at about sevennpence in the pound, Paddington at about fourpence, Saint James’s, Westminster, at about tenpence! It is only through the equalisation of Poor Rates that what is left undone in this wise, can be done. Much more is left undone, or is ill-done, than I have space to suggest in these notes of a single uncommercial journey; but, the wise men of the East, before they can reasonably hold forth about it, must look to the North and South and West; let them also, any morning before taking the seat of Solomon, look into the shops and dwellings all around the Temple, and first ask themselves ‘how much more can these poor people – many of whom keep themselves with difficulty enough out of the workhouse – bear?’

Someone else who was deeply moved by the images appearing in The Graphic was VincentVan Gogh. In January 1882, he wrote to his brother Theo:

I got a great bargain on some splendid woodcuts from The Graphic, some of them prints … Just what I’ve been wanting for years. .. I bought them from Blok, the Jewish bookseller, and chose the best from an enormous pile of Graphics and London News for five guilders. Some of them are superb, including the Houseless and homeless by Fildes (poor people waiting outside a night shelter) …and two large Herkomers and many small ones…

In short, it’s exactly the stuff I need…because, old chap, even though I’m still a long way from making them so beautifully myself, still, I have a couple of studies of old peasants and so on hanging on the wall that prove that my enthusiasm for those draughtsmen is not mere vanity, but that I’m struggling and striving to make something myself that is realistic and yet done with sentiment. I have around 12 figures of diggers and people working in the potato field,and I’m wondering if I couldn’t make something of them…

The Herkomer that Van Gogh refers to in the letter was Hubert von Herkomer who started his career as an illustrator for The Graphic, producing wood engravings of scenes of everyday life. He is regarded as a British artist, although he was born in Germany. There’s a painting of his in the collection of the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. Eventide: A Scene in the Westminster Union depicts inmates of the St.James’s Workhouse in Soho, London. Herkomer was drawn to the subject because of his sympathy for what he called ‘the sorrowful side of humanity’.

The final act of this exhibition reaches across 150 years to reveal the similarities of today’s London by night and the London by night described by Dickens, and the same ‘sorrowful side of humanity’ depicted in his novels and in the images of Fildes and Herkomer.

It’s a film commissioned specially for the exhibition called The Houseless Shadow. Film maker William Raban spent five months following Dickens’ footsteps through night-time London, filming places and people. The film, which lasts 20 minutes, uses Dickens essay Night Walks (read on the soundtrack) to explore parallels between London’s nocturnal life as it is today, compared with how it was when observed by Dickens 150 years ago.

Drip, drip, drip, from ledge and coping, splash from pipes and water-spouts, and by-and-by the houseless shadow would fall upon the stones that pave the way to Waterloo Bridge.

To the accompaniment of Dickens’ haunting essay Night Walks, we see shots of modern London at night with drunks and homeless people sheltering from the rain, filmed by Raban in a meditativeun obtrusive manner which matches the tone of Dickens’ text, where sympathy is pushed to the point of empathy with London’s poor and homeless.

Some years ago, a temporary inability to sleep, referable to a distressing impression, caused me to walk about the streets all night, for a series of several nights. The disorder might have taken a long time to conquer, if it had been faintly experimented on in bed; but, it was soon defeated by the brisk treatment of getting up directly after lying down, and going out, and coming home tired at sunrise.

In the course of those nights, I finished my education in a fair amateur experience of houselessness. My principal object being to get through the night, the pursuit of it brought me into sympathetic relations with people who have no other object every night in the year.

The month was March, and the weather damp, cloudy, and cold. The sun not rising before half-past five, the night perspective looked sufficiently long at half-past twelve: which was about my time for confronting it.

The restlessness of a great city, and the way in which it tumbles and tosses before it can get to sleep, formed one of the first entertainments offered to the contemplation of us houseless people. It lasted about two hours. We lost a great deal of companionship when the late public-houses turned their lamps out, and when the potmen thrust the last brawling drunkards into the street; but stray vehicles and stray people were left us, after that. If we were very lucky, a policeman’s rattle sprang and a fray turned up; but, in general, surprisingly little of this diversion was provided. Except in the Haymarket, which is the worst kept part of London, and about Kent-street in the Borough, and along a portion of the line of the Old Kent-road, the peace was seldom violently broken. But, it was always the case that London, as if in imitation of individual citizens belonging to it, had expiring fits and starts of restlessness. After all seemed quiet, if one cab rattled by, half-a-dozen would surely follow; and Houselessness even observed that intoxicated people appeared to be magnetically attracted towards each other; so that we knew when we saw one drunken object staggering against the shutters of a shop, that another drunken object would stagger up before five minutes were out, to fraternise or fight with it. When we made a divergence from the regular species of drunkard, the thin-armed, puff-faced, leaden-lipped gin-drinker, and encountered a rarer specimen of a more decent appearance, fifty to one but that specimen was dressed in soiled mourning. As the street experience in the night, so the street experience in the day; the common folk who come unexpectedly into a little property, come unexpectedly into a deal of liquor.

At length these flickering sparks would die away, worn out–the last veritable sparks of waking life trailed from some late pieman or hot-potato man–and London would sink to rest. And then the yearning of the houseless mind would be for any sign of company, any lighted place, any movement, anything suggestive of any one being up–nay, even so much as awake, for the houseless eye looked out for lights in windows.

Iconic landmarks evoke speculative thoughts in Dickens about the penal system, the borderline distinctions between sanity and madness, and the vastness of the numbers of London’s dead, lying in their burial grounds. Until I saw the section of this film that evokes Dickens’ circumnavigation of the Bethlehem Hospital, I hadn’t realised that ‘Bedlam’ still stands – now occupied by the Imperial War Museum:

From the dead wall associated on those houseless nights with this too common story, I chose next to wander by Bethlehem Hospital; partly, because it lay on my road round to Westminster; partly, because I had a night fancy in my head which could be best pursued within sight of its walls and dome. And the fancy was this: Are not the sane and the insane equal at night as the sane lie a dreaming? Are not all of us outside this hospital, who dream, more or less in the condition of those inside it, every night of our lives? Are we not nightly persuaded, as they daily are, that we associate preposterously with kings and queens, emperors and empresses, and notabilities of all sorts? Do we not nightly jumble events and personages and times and places, as these do daily? Are we not sometimes troubled by our own sleeping inconsistencies, and do we not vexedly try to account for them or excuse them, just as these do sometimes in respect of their waking delusions? Said an afflicted man to me, when I was last in a hospital like this, ‘Sir, I can frequently fly.’ I was half ashamed to reflect that so could I–by night. Said a woman to me on the same occasion, ‘Queen Victoria frequently comes to dine with me, and her Majesty and I dine off peaches and maccaroni in our night-gowns, and his Royal Highness the Prince Consort does us the honour to make a third on horseback in a Field-Marshal’s uniform.’ Could I refrain from reddening with consciousness when I remembered the amazing royal parties I myself had given (at night), the unaccountable viands I had put on table, and my extraordinary manner of conducting myself on those distinguished occasions? I wonder that the great master who knew everything, when he called Sleep the death of each day’s life, did not call Dreams the insanity of each day’s sanity.

Although there are striking differences from Dickens’s account of mid-Victorian London, some things remain the same, as when ‘the potmen thrust the last brawling drunkards onto the street’. What would Dickens, with his concern for social distress, make of the growing numbers of homeless on the streets of this prosperous city today? The resounding achievement of this exhibition is to relate Dickens’s London to the London of today. Two hundred years after his birth, London is once again a city of extremes and the social ills he writes about are as troubling as they were in his day.

Dickens was an insomniac and needed little sleep. He thought nothing of walking the streets of London all night. Through such regular excursions, he developed an encyclopaedic knowledge of London’s geography. Dickens had an extraordinary visual memory. He described his mind as a ‘sort ofcapitally prepared and highly sensitive [photographic] plate’. The variety and complexity of the city fed his creativity. As he walked, he mapped out the intricate storylines of his novels. Just as his fictional characters made their way from one place to another, so he followed in their footsteps across the real city. Dickens called the city his ‘magic lantern’ – a plethora of images and experiences that projected into his extraordinary imagination and helped him become, in the words of journalist Walter Bagehot, London’s ‘special correspondent for posterity’.

See also

Click the map to go to David Perdue’s interactive guide to Dickens’ London