The lighthouse on Pladda, with Ailsa Craig beyond, photographed from the front door on Kildonan shore

She had known happiness, exquisite happiness, intense happiness, and it silvered the rough waves a little more brightly, as daylight faded, and the blue went out of the sea and it rolled in waves of pure lemon which curved and swelled and broke upon the beach and the ecstasy burst in her eyes and waves of pure delight raced over the floor of her mind and she felt, It is enough! It is enough!

― Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

The last two summer holidays have been spent on Arran, in a cottage on the shore at Kildonan. We would sit on the bench by the door, gazing out to sea. Before us lay the low outline of the tiny island of Pladda with its lighthouse, while out further the hump of Ailsa Craig rose sheer from the sea, some 25 miles out yet appearing to be much closer.

So when my good friend Joe offered to lend me the memoir of a hippy art student, deep into poetry, Kerouac and Beefheart who spent the summer of 1973 working as a lighthouse keeper on Pladda and Ailsa Craig, I accepted eagerly. In Stargazing, Peter Hill recalls the glorious summer when, nineteen and fresh from art college, he spent six months working on various lighthouses off the Scottish mainland. Apart from his nostalgic reminiscences of early seventies music and politics, I learned a lot about the operation of lighthouses – that now all the lighthouses in the world are automated, an entire occupation eliminated in the decades following Hill’s apprentice summer; but when when manned (as they were back then), there would be three or four keepers working shifts.

Hill describes how a chance conversation in a pub that spring led to him pursuing one of those classic childhood ideas about what you’d like to do when you grow up. Like me, he imagined the life of a lone lighthouse keeper, daydreaming and stargazing the days away, reading poetry and listening to the latest offering from the Doors or Van Morrison. He had just read Desolation Angels, Kerouac’s semi-autobiographical account of months spent as a fire lookout on Desolation Peak in the mountains of Washington state (a book that had a mighty impact on me as well in my teenage years). So Hill, a long-haired 19-year-old art student turns up at 84 George Street in Edinburgh to be interviewed for the job of relief keeper – but let Hill take up the story, as he does in the book’s introduction:

In 1973 I worked as a lighthouse keeper on three islands off the west coast of Scotland. Before taking the job I didn’t really think through what a lighthouse keeper actually did. I was attracted by the romantic notion of sitting on a rock, writing haikus and dashing off the occasional watercolour. The light itself didn’t seem important: it might have been some weird coastal decoration, like candles on a Christmas tree, intended to bring cheer to those living in the more remote parts of the country.

I was 19 when I was interviewed for the job of relief keeper by the Commissioners of the Northern Lights in the New Town of Edinburgh. My hair hung well below my shoulders. I had a great set of Captain Beefheart records and I walked about with a permanent grin on my face as I had recently, finally, lost my virginity. I rolled my own cigarettes, was a member of Amnesty International and had just read Kerouac’s Desolation Angels. In short, I was eminently suitable for the job.

He gets the job, and for his first tour of duty is assigned to Pladda lighthouse. The night before he leaves, he gets down his father’s atlas and finds the island marked by a dot the size of a biscuit crumb. ‘Closer inspection showed it was in fact a biscuit crumb. I scratched it off and found an even smaller dot underneath this. This was Pladda.’

The lighthouse on Pladda, photographed from the front door on Kildonan shore

Arriving on Arran and following instructions from 84 George Street, he waits to be picked up by a local farmer for the next stage of his journey, who greets him with ‘Don’t tell me they’ve sent another fucking hippie!’ The farmer will take him by tractor from a remote field and deliver him to a rowing-boat which will take him to the lighthouse. The farmer’s greeting may have had something to do with the fact that Hill was standing on a wall a Scottish burn reading a Langston Hughes poem about a mighty river.

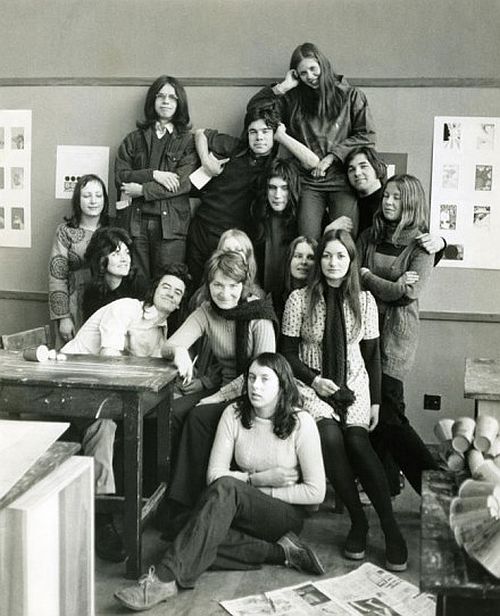

Peter Hill (top left) and the class of 71 Dundee Art College (photo: thisiscentralstation.com)

When Hill arrives on the tiny island of Pladda he learns that not only would he be sharing his new living quarters with three other men, but that he would also be participating in a bracing cooking rota. A pint of vegetable soup, followed by lamb casserole and apple crumble form his first lunch, served by Finlay Watchorn, who bears an uncanny resemblance to Captain Haddock. The keepers smoke like chimneys and drink endless tea poured from a kettle kept constantly at the boil. There’s a TV, on most of the time, and into this remote outpost are beamed daily the latest revelations from the Watergate hearings in Washington.

The least satisfactory aspect of the book for me were the constant references to Watergate and the popular shows on TV at the time: I just had a sense of Peter Hill having googled these things in order to provide some contemporary context. He also has an irritating (and, I think, inaccurate) tendency to portray every young person at the time as feeling they had no chance of escaping the fate of being conscripted to serve in Vietnam. Being roughly the same age at the time, I don’t remember it like that – yes, we were angry and marched against the war, but, in Britain at least, there was not that fear.

But those are small niggles; overall, I found Hill’s account of his glorious summer an entertaining read in which he brings to life some great characters – the men, a generation or two older than he, who had served in the war, worked as merchant seamen and who had experience of many lighthouses in all kinds of conditions. I learned that there are three types of lighthouse. Rock lighthouses come straight out of the sea and, as a keeper, you spend all your time in the tower. Coastal stations skirt the British Isles and are on the mainland, allowing keepers to live with their families. Island lights are situated on uninhabited islands. That summer Hill worked on all three of them.

I suppose if you had asked me, I would have suggested that all a keeper had to do was make sure the light was switched on at night. But from Hill’s account I learned that each light had three keepers, and each keeper took two four-hour watches every 24 hours. The watches rotated daily. Breakfast was always at eight, and always attended by all three keepers. When not attending to the light, the other two keepers would perform duties that, on an island lighthouse, ranged from shearing sheep to building jetties to painting the tower white. Each week a keeper would be assigned the important task of preparing a lavish three-course lunch.

Ailsa Craig, photographed from the the front door on Kildonan shore

Peter Hill served on three lighthouses that summer – two of them on islands that we would stare out at from our cottage at Kildonan – Pladda and Ailsa Craig. I discovered that Ailsa Craig, which looks from Arran like a rock rising sheer-sided from the sea, actually has a an area of flat land around its base. It is home to 20% of the world’s gannets – and a terrifying population of rats.

The lighthouse was built between 1883 and 1886 by Thomas Stevenson, member of an amazing family of lighthouse engineers, and father of Robert Louis Stevenson. Thomas Stevenson designed more than 30 lighthouses as engineer to the Board of Northern Lighthouses, while his father designed another 23, and invented the ‘intermittent’ light for lighthouses. Prevented by tuberculosis from pursuing a civil engineering career, Robert Louis Stevenson often travelled in search of warm climates better suited to his fragile health, writing the adventure novels for which he is famous – as well poems, including a couple inspired by his family’s profession:

The brilliant kernel of the night,

The flaming lightroom circles me:

I sit within a blaze of light

That’s an extract from ‘The Light-Keeper’. Stevenson also wrote a second poem on the same theme, ‘The Light-Keeper II’, from which come these verses:

As the steady lenses circle

With frosty gleam of glass;

And the clear bell chimes,

And the oil brims over the lip of the burner,

Quiet and still at his desk,

The Lonely Light-Keeper

Holds his vigil.

Lured from far,

The bewildered seagull beats

Dully against the lantern;

Yet he stirs not, lefts not his head

From the desk where he reads,

Lifts not his eyes to see

The chill blind circle of night

Watching him through the panes.

This is his country’s guardian,

The outmost sentry of peace,

This is the man

Who gives up what is lovely in living

For the means to live.

Among many other interesting insights in Peter Hill’s book are his comments about foghorns. ‘Nothing,’ he writes, ‘had quite prepared me for the painfully loud noise,’ or for the number of hours ‘turning into days’ that the foghorn might have to blow. Hill’s account of a conversation conducted in fifteen second bursts between deafening blasts of sound is hilarious, but will certainly give pause for thought for anyone who might have the idea of buying a lighthouse cottage. Not always per Virginia Woolf:

The sigh of all the seas breaking in measure round the isles soothed them; the night wrapped them; nothing broke their sleep, until, the birds beginning and the dawn weaving their thin voices in to its whiteness.

― Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

The last lighthouse that Hill worked on was on the island – no more than a rock – of Hyskeir in the Outer Hebrides. I laughed at his description of the island’s three goats which insisted that humans and goats walk in sequence across the island; if they failed to do so they would be butted into place. The correct order, Hill recalls, was goat, human, goat, human, goat. Hill also gives a vivid account of his last night on Hyskeir, an experience that brings to mind Hitchcock’s The Birds.

The men were already fraught – the helicopter which was due to collect them was fog-bound and they had to stay an extra night on the island with their tobacco ration exhausted. That night land birds migrating south from Scandinavia arrived in their tens of thousands, flying along the beam of light before endlessly circling the light. Though sea birds know to avoid lighthouses, land birds navigate southwards from beacon to beacon, many of them flying straight into the glass.

My watch started at 2 am. From the moment I woke up I was aware that there were birds everywhere. Dozens of them tapped against every window at ground level and the same manic mantra followed me up the 223 steps to the light room. Then things got worse. Because the light operated on paraffin there was a huge hole at the top of the tower to let the vapour escape and this, of course, let in the migrating birds. Some were fit and healthy, others had broken legs or damaged wings. There were at least fifty walking, flying and flapping wounded percolating around the light chamber.

Fearfully, I settled into a routine for the night. Every half an hour I would run up the stairs, wind up the light, pump up the paraffin, then disappear down to the kitchen while all around me a death rattle was tapped out on the inch-thick glass. At certain hours of the night every keeper on duty has to open the hatch in the light room and venture onto the balcony, often hundreds of feet above the sheer cliff face with only a low rail for protection. On the worst nights I had to pull myself round on my stomach because the winds were so strong. The point was to check that all the neighbouring lights were still burning. On the other lights, you soon realised, they would be doing exactly the same thing. The greatest sin was to let the light go out. The second greatest was to let the light stand so that it was burning but not turning. The night the birds came they were waiting for me on the balcony, sitting tightly shoulder to shoulder staring beyond me to the light. Behind them, tens of thousands of their flock circled in the beams of the light. Every few seconds another one would fly straight into the glass, break its neck and fall out of the sky. Not a night for a smoker to be without his poison.

The next day the flat roof of the outhouse was carpeted with dead birds – redbacks, wrens, tiny finches, thrushes. The keepers got ladders and for several hours threw the bodies into the sea.

Stargazing is heart-warming, nostalgic, and an elegy to a vanished profession. But it’s also an elegy to youth – to being nineteen and at an age when music and poetry, life and dreams for the future are felt with more intensity than they ever will be again.

But it may be fine -I expect it will be fine,’ said Mrs. Ramsay, making some little twist of the reddish-brown stocking she was knitting, impatiently. If she finished it tonight, if they did go to the Lighthouse after all, it was to be given to the Lighthouse keeper for his little boy, who was threatened with a tuberculous hip; together with a pile of old magazines, and some tobacco, indeed whatever she could find lying about, not really wanted, but only littering the room, to give those poor fellows who must be bored to death sitting all day with nothing to do but polish the lamp and trim the wick and rake about on their scrap of garden, something to amuse them. For how would you like to be shut up for a whole month at a time, and possibly more in stormy weather, upon a rock the size of a tennis lawn? she would ask; and to have no letters or newspapers, and to see nobody; if you were married, not to see your wife, not to know how your children were, if they were ill, if they had fallen down and broken their legs or arms; to see the same dreary waves breaking week after week, and then a dreadful storm coming, and the windows covered with spray, and birds dashed against the lamp, and the whole place rocking, and not be able to put your nose out of doors for fear of being swept into the sea? How would you like that? she asked, addressing herself particularly to her daughters. So she added, rather differently, one must take them whatever comforts one can.