In the years of optimism we would read books and puzzle over why, in the heart of civilized Europe, people had happily abandoned democracy, believed fantastical lies, and stood by or enthusiastically joined in as those deemed to blame for the nation’s ills were murdered in their millions. In these dark days, and on this Holocaust Memorial Day, understanding is beginning to gnaw at our bones like an ague.

In times like these, the message of certain books I have read recently seems to illuminate a simple truth: that authoritarianism insinuates itself into peoples lives without drama, but with a kind of quotidinian ordinariness that slowly dispenses with facts.

This truth was one pinpointed by Hannah Arendt in 1950 in The Origins of Totalitarianism:

The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the dedicated communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction, true and false, no longer exists. […] Before mass leaders seize the power to fit reality to their lies, their propaganda is marked by its extreme contempt for facts

In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true. … Mass propaganda discovered that its audience was ready at all times to believe the worst, no matter how absurd, and did not particularly object to being deceived because it held every statement to be a lie anyhow.

On the south-west outskirts of Berlin, in the birch-clad woodlands north of Potsdam and Wannsee, there is a lake, and along the shore of that lake, during the 1920s, a wooden summerhouse was built. In the turbulent century that followed, the building would be lived in and lost by five families. In The House by the Lake, Thomas Harding narrates a brilliant history of 20th century Germany through the story of a single house. Reading this book reveals the way in which a community can begin to live with injustice, prejudice and authoritarian rule.

It’s a small, wooden house in a village called Gross Glienicke, built as a summerhouse by Harding’s great-grandfather Alfred Alexander, a successful Jewish doctor living in Berlin, after the First World War. For six summers, the Alexander family would abandon the city’s bustle for the calm of their lakeside retreat, to swim and relax by the water.

Harding begins his story, not with the Alexanders, but in the 1890s with the Wollanks, the family that owned the estate whose land bordered the lake. This allows Harding to trace the changing fortunes of Otto Wollank’s Brandenburg manor, sixteen kilometres outside Berlin, the burgeoning capital of the new German empire. In the years leading up to the First World War, Otto’s efforts transform the estate from a feudal backwater into a model farm making money from products including milk, grapes and bricks that served the needs of the dynamic city on its doorstep.

But the war and Germany’s post-war instability, devastate the finances of the estate, so that in 1927 Otto decides to lease parcels of land along the lake shore to satisfy the growing appetite of better-off Berliners for a second home in the country, but only a short drive away from the city centre.

The Alexanders came to view the parcel of land that sloped down to the lake one spring day in 1927. A deal was struck and they hired a berlin-based builder to construct their summerhouse. Along with a neighbouring house, theirs was the first weekend retreat to be built at Gross Glienicke.

Before entering the house for the first time, the Alexanders gathered by their front door. In one hand, Alfred held a hammer and some nails he had brought from Berlin. In the other was a mezuzah, a metal cylinder which held a tiny scroll containing the ancient Hebrew words: ‘Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one.’ After saying a short prayer, he tacked the mezuzah onto the right-hand side of the main entrance. Then, opening the black-painted wooden door, Alfred invited his children to explore the house. Delighted, Bella, Elsie, Hanns and Paul ran ahead.

Then Hitler took power and the owner of the Gross Glienicke estate joined the Nazi Party and gave permission for the brown-shirted thugs of the Nazi paramilitary SA to set up a training camp near the village. The Alexanders’ place of retreat and solitude had to be abandoned when the family was forced to flee to Britain in 1936, the year of the Berlin Olympics.

For eight months the house by the lake stood empty. Then, in the Nazi party’s rpcess of ‘aryanisation’, the Alexanders property was expropriated as reparations for the economic damage that the Nazis claimed the Jews had inflicted on the German people. The leasehold was transferred to an unscupulous composer and music publisher, Will Meisel.

The cabin was now the Meisel summer home, but the wheel of fortune turns, and as profiteers from the Nazi years, they were forced to flee in their turn. In 1945, the Russians conquered Berlin and the city was divided into occupation zones. The new border left most of the summerhouses by the lake, including the Alexanders’ old place and the village of Gross Glienicke, in the Soviet zone.

With the establishment of the East German Republic, the house was appropriated by the local government and a summer cabin lacking adequte heating or insulation became a year-round home for the first time. A succession of families moved in until in 1962, overnight, the Berlin Wall was thrown up, across the garden and blocking access to the lake. Then, just as suddenly as it went up, the Wall came down in 1989. West Germans whose summerhouses had been nationalised and inaccessible for a generation now turned up in Gross Glienicke, seeking to repossess their long-lost property.

Thomas Harding’s book is the story of all the individuals who lived in the Alexander’s house, but more than that it is a remarkable social history, tracing the tremendous upheavals experienced by Germans in the twentieth century. Based on extensive archival research, by structuring his narrative around deeply personal stories, Harding has produced a gripping and comprehensible account of recent German history.

With the rest of her family, Harding’s grandmother fled Nazi Germany and settled in England. She never saw the summerhouse again until the summer of 1993, when Thomas Harding travelled to Germany with her to revisit the house that had been her ‘soul place’ as a child. They found it abandoned and derelict.

It was government property now, and soon to be demolished. Could it be saved? And should it be saved? Harding began to make tentative enquiries – speaking to neighbours and villagers, visiting archives, and slowly piecing together the lives of the five families who occupied the house, discovering that all of them had, for different reasons, been forced out.

As the story of the house began to take shape, Harding realised that there was a chance to save it as a community resource. But in doing so, he would not only need to convince local people; he would also have to challenge his own family’s feelings towards their former homeland. Harding tells that part of the story in ‘interludes’ interspersed throughout the book (while the progress of the Alexander Haus project continues to be updated on its website).

The House by the Lake is a suberb book, taking the reader on a journey through 2oth century German history, from the nobleman’s estate in the years before the First World War, to the years when the summerhouse was occupied, first by the prosperous Jewish family, before falling into the hands of the music publisher and Nazi sympathiser; then through the postwar years of a divided Germany when the house was lived in throughout the year. Harding’s evocative writing and meticulous research reminded me of another story told about Jews who lost their patrimony during the Nazi period: Edmund de Waal’s The Hare With Amber Eyes, which focused on a group of netsuke – small Japanese figurines – that was all that remained of his family’s once-rich art collection.

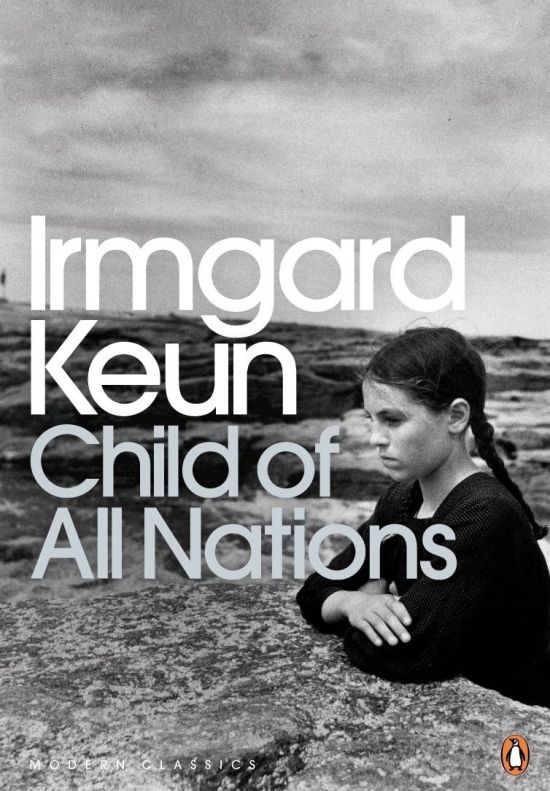

If The House by the Lake conjures a powerful sense of how people in a small community can easily come to terms with their near-neighbours being stigmatised, brutalised, stripped of their rights and their property, then forced into exile or taken away to an uncertain but easily-guessed fate, four more books I’ve read recently took me back to the years when fascist parties rose to power and Europe stumbled towards darkness. In Summer Before the Dark: Stefan Zweig and Joseph Roth, Ostend 1936, Volker Weidermann has produced a fictionalised portrait of exiled artists and intellectuals holed up in the Belgian resort as fascism’s grip on Europe tightens. The middle-aged alchoholic wanderer and brilliant journalist Joseph Roth is there (I’ve been reading two collections of his feuilletons from the 1920s and 30s – What I Saw: Reports from Berlin 1920-33, and The Hotel Years), drinking heavily and sharing a hotel room with Irmgard Keun – ‘young, suntanned and merry’, her novels blacklisted by the Nazis for their ‘immoral’ depictions of modern young women. The novel she writes while in Ostend – Child of All Nations – is the fourth of the books I’ve read which, drenched in a sense of impending disaster, conjure that world of exiles driven from their homelands by authoritarian regimes which once seemed so distant, though less so now.

‘I belong nowhere now, I am a stranger or at the most a guest everywhere,’ wrote Stefan Zweig in a memoir completed in Brazil shortly before his suicide in 1942. In Volker Weidermann’s Summer Before the Dark, Zweig strolls the seafront at Ostend in 1936, waiting for his friend Joseph Roth to arrive. Also in town are other exiles – banned writers and Communists in the main, most of them Jewish but some not – waiting with their wives and mistresses as storm clouds gather over the rest of Europe.

When Joseph Roth arrives he is quickly distracted by another writer, the daring and provocative Irmgard Keun, author of a series of bestselling, radically feminist novels published in Germany during the Weimar years. Both share a sense that life is short, and they move into the Hotel Couronne together where they make love and write, urging each other on. When they aren’t in bed or writing they meet up with other émigrés to gossip, compete and hold forth about art and politics, their discussions always tinged with fear. The impending ‘criminal’ Olympic Games in Berlin fill them with dread as the Nazi propaganda machine goes into overdrive, papering over its crimes, its hate:

The regime has been busy donning a disguise for weeks, divesting itself of the visible signs of anti-Jewish and anti-foreign policies and presenting itself as a civil state comitted to international friendship. All ‘Forbidden to Jews’ signs have been taken down. ‘And have you heard?’ asks Ernst Toller [the exiled German playwright]. ‘Der Stürmer has been censored for weeks. Not to remove any statements, just the anti-Semitic passages.’ ‘Wonderful!’ So now they’re selling blank paper!’ is Roth’s bitterly mocking retort.

This is how Volker Weidermann sets the mood in the opening passage of this unclassifiable blend of novella and literary memoir:

It’s summer up here by the sea; the gaily colored bathing huts glow in the sun. Stefan Zweig is sitting in a loggia on the fourth floor of a white house that faces onto the broad boulevard of Ostend, looking at the water. It’s one of his recurrent dreams, being here, writing, gazing out into the emptiness, into summer itself. Right above him, on the next floor up, is his secretary Lotte Altmann, who is also his lover; she’ll be coming down in a moment, bringing the typewriter, and he’ll dictate his Legend to her, returning repeatedly to the same sticking point, the place from which he cannot find a way forward. That’s how it’s been for some weeks now.

Perhaps Joseph Roth will have some advice. His old friend, whom he’s going to meet later in the bistro, as he does every afternoon this summer. Or one of the others, one of the detractors, one of the fighters, one of the cynics, one of the drinkers, one of the blowhards, one of the silent onlookers. One of the group that sits downstairs on the boulevard of Ostend, waiting for the moment when they can go back to their homeland. Racking their brains over what they can do to change the world’s trajectory so that they can go home to the country they came from, so that in turn they can maybe even come back here on a visit one day. To this holiday beach. As guests. For now, they’re refugees in vacation-land. The apparently ever-cheerful Hermann Kesten, the preacher Egon Erwin Kisch, the bear Willi Muenzenberg, champagne queen Irmgard Keun, the great swimmer Ernst Toller, the strategist Arthur Koestler: friends, foes, storytellers thrown together here overlooking the sand in July by the vagaries of world politics. And the stories they tell will be the fragments shored against their ruin.

Stefan Zweig in the summer of 1936. He looks at the sea through the large window and thinks with a mixture of pity, reticence, and pleasure about the group of displaced men and women he will be joining again shortly. Until a few years ago, his life had been a simple, greatly admired, and greatly envied ascent. Now he’s afraid …

Joseph Roth and Stefan Zweig make an unlikely pair. Zweig, the elegant Viennese Jew, then 53, is ‘self-confident, worldly, with a firm stride, like an elegant shrew in his Sunday best’. Roth, the scruffy, penniless eastern Jew, 13 years younger, is already in the advanced stages of alcoholism, his feet so swollen he can hardly put on a pair of shoes. He barely eats, throws up for hours every day, and is constantly touching Zweig for cash. Zweig pays his bills, buys him new clothes, makes him eat and take exercise, and tries in vain to curb his drinking.

But Roth is a magnet for the others, a marvellous raconteur, ‘better in conversation than in his books’ and Zweig and Roth share a literary sensibility and emotional affinity. Wiedermann slowly reveals the literary debt each man owes to the other, with in one instance Roth suggesting a crucial scene for a short story Zweig is writing. They live for their writing. It confirms their existence while their works are being burned and destroyed at home. Irmgard Keun, Roth’s young lover, says that she and Roth engage every day in ‘the purest literary Olympics,’ working at opposite ends of a cafe and then at the end of the day counting who has written the most pages.

Joseph Roth, a poor eastern Jew, had been born in 1894 in Brody, a predominantly Jewish town in Eastern Galicia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and he always felt the collapse of that multinational entity as a personal loss. His best-known work, the novel The Radetzky March, is imbued with a sense of nostalgia for a lost homeland. From 1920 to 1933, he lived in Berlin, writing the brilliant journalistic pieces of social observation – known as feuilletons – that have recently been gathered together in collections such as What I Saw. In 1933 Roth abandoned Germany for good (his wife Friederike, mentally ill and confined to an asylum, had been euthanised after the Nazis took control, though Roth never knew) and, after roaming around Europe for a while, settled in Paris. It was there that he learned that The Radetzky March was amongst the books burned by the Nazis in March 1933. At that moment, Roth wrote in a letter to his friend, the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig:

Very few observers anywhere in the world seem to have understood what the Third Reich’s burning of books, the expulsion of Jewish writers, and all its other crazy assaults on the intellect actually mean. The technical apotheosis of the barbarians, the terrible march of the mechanized orangutans, armed with hand grenades, poison gas, ammonia, and nitroglycerine….all that means far more than the threatened and terrorized world seems to realize. It must be understood. Let me say it loud and clear. The European mind is capitulating. It is capitulating out of weakness…out of lack of imagination…as the smoke of our burned books rises into the sky. […] You will have realized by now that we are drifting towards great catastrophes. Apart from the private — our literary and financial existence is destroyed — it all leads to a new war. I won’t bet a penny on our lives. They have succeeded in establishing a reign of barbarity. Do not fool yourself. Hell reigns.

Stefan Zweig was quite different: the son of a prosperous textile manufacturer, he was the embodiment of the assimilated Jew – urbane, elegant, tolerant. But when he arrives in Ostend, he is also a man in crisis, having lost his home in Salzburg, and his livliehood (Jews are no longer welcome in print) after the Nazi takeover of Austria. Estranged from his wife, he has fallen in love with his secretary, Lotte Altmann.

As Europe faced its darkest days, Zweig was a passionate voice for tolerance, peace and a world without borders. In essays composed before and during the Second World War, he argued the case for a Europe free of nationalism and pledged to pluralism, culture and brotherhood:

Darkness must fall before we are aware of the majesty of the stars above our heads. It was necessary for this dark hour to fall, perhaps the darkest in history, to make us realize that freedom is as vital to our soul as breathing to our body.

In Summer Before the Dark, Weidermann writes:

The universe, literature, politics – wouldn’t it be wonderful never to have to think about them again? Where would be the farthest place from it all? A beach in Belgium, white house, sun, a broad promenade, little bistros looking out over the water. He wants Ostend. With Lotte. He brings her along.

For me, it was Roth who leapt from the Weidermann’s pages. I had already read The Radetzky March, and his hallucinatory novella of alcoholism, The Legend of the Holy Drinker, but now I set about reading his journalism. In What I Saw, the fine collection edited and translated by Michael Hofmann, there is a piece entitled ‘The Man in the Barbershop’, which is striking to read in present circumstances. In his review for the Guardian in 2004, Nicholas Lezard noticed the scene, described in Roth’s deceptively simple prose:

The bore in the barber shop (‘he is duty and decency, sour-smelling and clean’) may not be a Nazi yet – it’s 1921 – but he will be soon. And the young political scout groups are already, in 1924, ‘on the repellent shrieking edge of hysteria’. There is a lot of this book that has to be read on the edge of your seat.

Paul Scraton, on his excellent Berlin blog has also commented on this piece:

The boorish man who enters the barber shop starts to dominate the conversation, and regardless of where us readers live, in which place or in which time, we can recognise the type immediately. He wants attention. He wants to own the room. And he wants agreement for his thoughts, that are immediately obnoxious:

‘The farther north you go,’ he says, early on in his monologue, ‘the more nationalist people are. In Hamburg they’re really excited about Flag Day. Well, you’ll see. It’s on its way. Can’t be stopped. On, on!’

The man dominates the conversation so much that even the fly that had previously been buzzing around the half-shorn heads and lathered jaws of the patrons is given pause to stop, still on the wall. Roth, meanwhile, makes his own contribution in response to the man’s opening salvo:

‘And if you – I think – were to go south, or west, or east, it would be just the same. Whichever way you went you’d see people getting more nationalistic. Because what you see is blood…’

Paul Scraton continues perceptively:

As a reader you imagine the scene and you can hear the voice. Only the voice we hear now is not talking about Hamburg in the early 1920s but about Dover in 2016, about an alternative for Germany or a democratic renewal in Sweden. We know this voice because he is insisting on what women wear on a French beach or imagining how to make America great again. The man in the barbershop does not belong to history. He belongs to the here and now.

Joseph Roth’s non-fiction bears witness to the slow descent into darkness that followed the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the onset of Nazi barbarism. In 1933 he wrote a letter from exile in Paris to his friend, Stefan Zweig:

You will have realized by now that we are drifting towards great catastrophes. Apart from the private – our literary and financial existence is destroyed – it all leads to a new war. I won’t bet a penny on our lives. They have succeeded in establishing a reign of barbarity. Do not fool yourself. Hell reigns.

In Ostend in 1936, Roth and Irmgard Keun are firing each other up, creatively and physically. Weidermann’s depiction of Keun in Summer Before the Dark led me to the book she was writing, back-to-back with Roth, in that summer in Ostend, Child of All Nations.

Irmgard Keun may have been the only person brave enough to attempt to sue the Nazis for banning her best-selling books and causing her to lose royalties.This is how Weidermann introduces her in Summer Before the Dark:

She’s a self-confident, beuatiful young woman, a fur around her neck, a wide mouth, big eyes. And she thought, if anyone was going to start banning books around there, she was going to see about it. […]

She herself had naturally never expected things to come to trial. But she simply couldn’t put up with it. How could a new government come in and proceed to confiscate her books just like that? Irmgard Keun has a childlike propensity to question absolutely everything.

Blacklisted, Keun went into exile, wandering across Europe and settling briefly in places such as Ostend. As Michael Hofman, translator once again, writes in his introduction to Child of All Nations, ‘one could, if one had a mind to, follow her movements in those years via Child of All Nations.’

For the novel, narrated brilliantly by Keun in the voice of a nine-year-old girl, is the story of such wanderings. Headstrong, defiant and intelligent, Kully might not attend school, but she knows all about visas and passports and has an ever-expanding repertoire of languages. She is, in Hofmann’s words, ‘the oldest and wisest character in the book – her mother’s keeper, her father’s agent.’

When I was in Germany, before, I did go to school, and that’s where I learned to read and write. Then my father didn’t want to be in Germany any more, because the government had locked up friends of his, and because he couldn’t write or say the things he wanted to write and say. I wonder what the point is of children in Germany still having to learn to read and write?

Her father, the alcoholic and unreliable writer Peter, is widely regarded as a portrait of Keun’s Ostend lover, Joseph Roth – badgering advances from publishers, pawning items from their meagre belongings, and begging from the rich. Kully and her sad, harassed mother Annie camp out in hotel rooms, running up bills and avoiding staff who might be waving bills.

Keun’s genius is to paint for us a vivid picture of these dislocated, wandering souls in a Europe on the edge of war and to do it in the words of a preternatural nine year old. Through Kully’s eyes, we glimpse the chaotic life of her alcoholic father, constantly on the edge of financial disaster, and the constant anxiety of the displaced person who has no permanent residence and can never return home.

My mother read to me from the Bible. It says there that God created the world, but it doesn’t say anything about borders….I always wanted to see a border properly for myself, but I’ve come to the conclusion that you can’t. My mother can’t explain it to me either. She says: ‘A border is what separates one country from another.’ At first I thought borders were like fences, as high as the sky. […] But …a border has nowhere for you to set your foot. It’s a drama that happens in the middle of a train, with the help of actors who are called border guards.

Child of All Nations is full of terrific passages like this one in which Kully’s father (sounding extraordinarily like Roth) argues with a group of Dutch people about religion:

As for fear of God? Why? Why not trust in God? I’d rather my little girl worshipped matchboxes or liqueur glasses than that she be afraid of God. Everything that’s wrong in the world begins with fear. All that mess in Germany could only result because the people there have lived in fear for ever. No sooner is a child born than fear of its mother and father is instilled into it. And then it has to honour its father and mother as well. Why? Either you love your parents, in which case you honour them as a matter of course, or you don’t love them, in which case your honouring them isn’t going to do them a blind bit of good. First a father demands that his child be afraid of him. Then there’s school and fear of the teacher, fear of God at church, fear of military or other superiors, fear of the police, fear of life, fear of death. Finally, the people are so crippled and warped by fear that they elect a government that they can serve in fear. Not content with that, when they see other people who are not set on living in fear, the get angry, and try in their turn to make them afraid. First of all they make God into a kind of dictator, and now they don’t need Him any more, because they’ve come up with a better dictator themselves.

Everything seen through Kully’s eyes, the book has many funny moments. But always there is a sense of impending doom. Kully’s mother is frightened when she hears someone singing the Horst Wessel song in the street outside their hotel.

People tremble when they buy newspapers and magazines: what’s going wrong with the world? I’d so much like to have another child to play with.

One day in Ostend Kully’s mother is distraught to read in a Swiss newspaper something about Uncle Pius, Kully’s favourite uncle whom they visited in Vienna a year ago.

Uncle Pius laughed a lot and he was very good to us. Now we can’t go back to see Uncle Pius or Vienna, because the German government has occupied it all.

We know lots of people who ran away from Vienna, including even some children. The silly thing is that when you run away from those countries, you have to go as you are, you can’t take your house or your money with you. … Uncle Pius has a big hospital in Vienna – how is he going to take that with him?

My father says the German government locked people up who didn’t even steal anything. Who would want to live in a country like that?

‘Uncle Pius is dead,’ says my mother. ‘Just a minute, I’ll be right back.’ She’s crying, and runs off with the newspaper under her arm.

Joseph Roth, still wandering, died in Paris in May 1939, collapsing at the Café Tournon, a year before the German occupation. Always the melancholic alchoholic, he wrote that he was ‘all washed up … I take more time dying than I ever had living’, and that year he had published The Legend of the Holy Drinker, a fable about an alcoholic with a heart of gold, on which subject he was an expert.

In May 1938, following Roth’s death, Keun crossed the Atlantic, but after eight weeks she crossed back. In 1940, after the fall of the Netherlands, she ‘did the ofddest thing’ (Hofmann’s words): she returned to Germany and lived there semi-legally under an assumed name, surviving unscathed because word got around that she’d committed suicide. She died in 1982, aged 77, her later years marred by episodes of hospital treatment for alcohol-related illnesses.

As for Stefan Zweig and his wife, in 1940 they settled for a while in Connecticut, before moving again to Petrópolis, a German-colonized mountain town north of Rio de Janeiro. Depressed by the spread of intolerance and the growing power of Nazi Germany, and feeling hopeless for the future for humanity, with his wife Zweig committed suicide, leaving this note about his feelings of desperation: ‘I think it better to conclude in good time and in erect bearing a life in which intellectual labour meant the purest joy and personal freedom the highest good on Earth.’

Paul Scraton, in a post on his blog Under a Grey Sky, sums up the effect of reading these books as generating a ‘sense of impending doom’:

To read all these books now is to imagine the wave slowly building, about to crash over them, and to realise that all three writers knew what was coming but were powerless, in their imagination or otherwise, to stop it.

I’m not entirely sure about that. Stefan Zweig, in one of his essays and speeches now collected in Messages from a Lost World: Europe on the Brink, imagined a different future:

If men lived [in earlier eras] as if in the folds of a mountain, their sight limited by the peaks on either side, we today see as if from a summit all worldly happenings in the same moment, in their exact dimensions and proportions. And because we have this commanding view across the surface of the earth, we must now usher in new standards. It’s no longer a case of which country must be placed ahead of another at their expense, but how to accomplish universal movement, progress, civilization. The history of tomorrow must be a history of all humanity and the conflicts between individual countries must be seen as redundant alongside the common good of the community.

Read more

- Holocaust Memorial Day 2017

- Saving the house we lost to the Nazis (Thomas Harding, Guardian, 2015)

- Saving a Relic of Jewish Life in Germany (New York Times)

- Alexander Haus: website of the community preservation organisation

- A walk in Berlin’s Green Forest (this blog)

- Stumbling over the past in Berlin (this blog)

- The Radetzky March: elegy for an empire (this blog)

- Democracy without populism: readiong Joseph Roth: Paul Scraton’s blog post

- I learned to see Joseph Roth as his own solar system: article by his translator Michael Hofmann(Guardian)

- Emperor of Nostalgia: review of Roth’s collected stories by J.M. Coetzee(New York Review of Books)

- Blacklisted, exiled, mistreated, forgotten… the unsinkable Irmgard Keun

Reblogged this on Passing Time and commented:

For Holocaust Memorial Day, reblogged from That’s How the Light Gets In

Even the amoeba and paramecium “got it.” Cooperation and individual sacrifice are the pillars of evolution. Question is: “Given that humans can see it, can the powerful .001% in their bunkers be stopped?”

Astute as always – but the woman in the portrait is not Irmgard Keun, but Jewish poet Mascha Kaléko!

Thanks for the correction, Katie. A google image search sent me to a page that presented that image as Keun. I’ve replaced it with one from her German publisher’s website – so I assume I’ve got the right one this time!

Thanks for this beautiful and important article! The woman walking next to Joseph Roth, however, is NOT Irmgard Keun, but Roths wife Friederike (Friedl) Roth-Reichler. The picture was taken in Berlin, presumably 1928.

Another misattribution! Thanks for the correction, Femke. I have corrected the caption.

Reblogged this on folio.