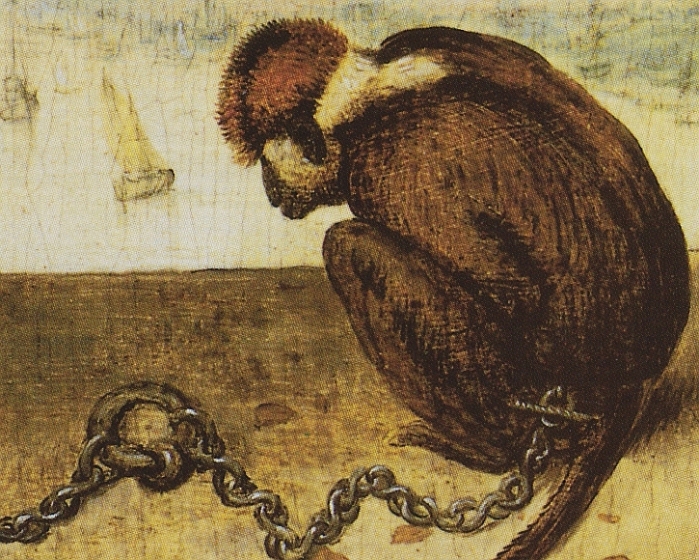

It’s only a small painting – barely seven inches by nine – yet (though I know such comparisons are invidious) if I were asked to list my ten favourite artworks this would be one of them. Pieter Bruegel’s Two Monkeys is haunting, mysterious and profound.

Two Monkeys is one of two Bruegel paintings that we found in Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie – another way-station in our pursuit of Bruegel through the museums of Europe. The other couldn’t be more different: Netherlandish Proverbs is large (4 feet by 5), populated by a vast crowd of people engaged in all kinds of activities and social interactions. One is deeply meditative, even pessimistic, while the other’s vast canvas celebrates the complexity and richness of urban life.

Two hunched and dejected monkeys are chained in the window of a fortress that overlooks the river Scheldt. In the distance, the skyline of Antwerp can just be made out in the haze, sailing ships anchored in the harbour. Birds wheel in free flight over the river.

Immediately you are confronted by two questions: how did the monkeys come to be in Antwerp, and why are they shackled? Possible explanations lead to the realisation that this is a painting which confronts the viewer with profound questions about the economic system that was establishing itself across Europe in Bruegel’s day, and about man’s relationship with the natural world.

Bruegel had spent much of the decade before he painted Two Monkeys in Antwerp, at a time when the city was ruled by the Spanish Habsburg dynasty, and had developed into a major centre of world trade and the most important money market of Europe dominated by German merchants like the Fuggers of Augsburg. Luxury imports arriving at Antwerp harbour would have included rare specimens from Africa, such as these monkeys, which Bruegel has painted with great realism and obvious care for detail.

Fernand Braudel, the great historian of the rise of capitalism in Europe, wrote that the city had never been so prosperous. It was constantly expanding: the population had been no more than 49,000 in 1500, but by 1568 it was probably 100,000. The city was covered with building sites, as new squares were designed and new streets cut.

A new economic infrastructure was constructed: luxury, capital, industry and culture all bloomed together, with a growing gap between the rich who became richer and the poor – a growing proletariat of unskilled labourers like porters, dock-workers, and errand-boys – became poorer.

This was the moment – and the place – where the global economy of the 21st century began to take shape. The rapid development of 16th century capitalism provided civilization, comfort and wealth for the few – but at what cost? That is the question Bruegul poses in Two Monkeys.

The wealth of Antwerp’s merchant class provided Bruegel with a comfortable position. It was in Antwerp that Bruegel achieved artistic and commercial success – not least, due to the fact that Nicolaes Jongelinck, prominent merchant, was an avid Bruegel collector. At one point he owned 16 Bruegel paintings, including The Tower of Babel and The Procession to Calvary. Some time around 1565 (before Bruegel’s death), the city of Antwerp assumed ownership of Jongelinck’s Bruegels after he had posted them as security for a loan on which a friend defaulted. The paintings later became the property of the governor of the Netherlands, and then Rudolf II, the Hapsburg ruler (which is why so many of them can now be found in Vienna).

But Bruegel’s were not the conventional paintings – society portraits or religious narratives – produced at the time for rich patrons. Bruegel chose secular subjects (or religious subjects transposed into the world of Flemish peasant folk or urban workers), realism rather than allegory. However, both the Berlin paintings are examples of how he used popular Flemish proverbs which he depicted literally in peasant or urban settings.

On the right hand side of the sill in Two Monkeys bits of cracked hazelnut shell are strewn around, alluding to the Netherlandish proverb ‘went to court for the sake of a hazelnut’ – in other words, ‘traded freedom for small reward’: a suggestion that the monkeys have lost their freedom for the sake of something as small as the kernel of a hazelnut.

It’s quite possible that Bruegel had seen monkeys like these in Antwerp, imported from the New World and displayed in shackles as trophies of the owner’s wealth. Maybe he was moved by their plight. But, I think that Bruegel’s point is that it is not only the monkeys that are enslaved: their owners are, too. With the city of Antwerp visible in the distance, Bruegel suggests that the prosperity of the city that has afforded him success rests on a system in which men sell their souls for material riches: one founded upon exploitation and inhumanity, and the enslavement of human beings by their fellow-men. By this interpretation, the chains on the monkeys represent the suffering brought about by contempt for the dignity of fellow human beings.

But there is more going on here. Bruegel frames the scene within the arch of the fortress window: we are inside the prison cell with the monkeys. As Robert Bonn writes in Painting Life: The Art of Pieter Bruegel the Elder:

Whatever the message, the intrigue of the whole scene is enhanced once we place ourselves as viewers trapped in a dungeon looking at Antwerp from the perspective of two monkeys!

There is always more than one interpretation that can be placed on a painting like this. Given that Bruegel quite often imported into his pictures a critique of the abuse of power (most notably in The Massacre of the Innocents, painted two years later), Two Monkeys could also symbolize the oppression of the Flemish provinces under Spanish rule.

We will never know what prompted Bruegel to paint this picture, but the dejection of the imprisoned creatures that form its subject, contrasted with the unattainable urban panorama and the freedom of the birds on the wing visible from their place of incarceration continue to reach out to those who view the picture centuries later.

Auden was famously moved to write Musée des Beaux Arts after seeing Bruegel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus while staying with Christopher Isherwood in Brussels in December 1938. But he’s not the only poet to have been inspired by a Bruegel painting. In her younger days, the Nobel prize-winning Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska wrote averse entitled Bruegel’s Two Monkeys. The poem appeared in the Polish literary weekly Zycie Literackie (Literary Life) in June 1957; a year earlier in Poznan riots by workers protesting at shortages of food and consumer goods, bad housing, and wage cuts had been followed by demonstrations throughout Poland that lasted into the autumn. As Soviet troops gathered along the border only an October compromise allowed Poland to avoid the fate of Hungary that year.

Like many intellectuals following the establishment of communist rule in Poland at the end of the Second World War, Szymborska at first supported the party line, but gradually she grew estranged from official ideology and renounced her earlier political work. Although she did not officially leave the party until 1966, she began to establish contacts with dissidents.

In the New York Times Book Review, Stanislaw Baranczak wrote:

The typical lyrical situation on which a Szymborska poem is founded is the confrontation between the directly stated or implied opinion on an issue and the question that raises doubt about its validity.

In Szymborska’s poem the speaker is confronted by a test, an oral examination. It’s her graduation exam, and she feels as if she is failing. She stammers and falls silent when asked about the history of humanity. The point being that answering a question, or writing a poem about recent history in Poland in 1957 was not easy. But, a monkey rattles its chain, and, perhaps, something shifts in her thinking.

This is what I see in my dreams about final exams:

two monkeys, chained to the floor, sit on the windowsill,

the sky behind them flutters,

the sea is taking its bath.

The exam is the history of Mankind.

I stammer and hedge.

One monkey stares and listens with mocking disdain,

the other seems to be dreaming away –

but when it’s clear I don’t know what to say

he prompts me with a gentle

clinking of his chain.

Proverbs were an important means of expression in Bruegel’s day, a popular way in which moral values, religious principles, social prescriptions or prejudices could be succinctly stated. Bruegel wasn’t the only artist to illustrate proverbs, but no other artist came close to his ordered portrayal of at least 112 proverbs in the integrated scene we are presented with in the vast canvas of Netherlandish Proverbs.

Brueguel had already completed a series of Twelve Proverbs on individual panels; now he tackles a hundred more. (We saw Twelve Proverbs at the Museum Mayer in Antwerp a couple of years ago). Bruegel’s aim in both cases was to entertain at the same time as instructing. Absurdity, wickedness and the foolishness of humans are regular themes in his work, and The Netherlandish Proverbs is no exception. The painting’s original title, The Blue Cloak or The Folly of the World, indicates that Bruegel’s intention was not simply to illustrate a bunch of proverbs, but to focus on what they said about the absurdity of much of human behaviour.

The painting displays folly in all its incarnations. What’s interesting is that Bruegel’s intent was likely more serious than simply provoking belly laughs at the parade of foolishness on show here. The fool emerged as a thought-provoking figure in the literature of the early Renaissance, as well as serving as a mouthpiece for humanist philosophers such as Erasmus. These writers used the fool to highlight ambiguities and contradictions in religious teaching at a time when the world that was flat was becoming round, and the truth of theology was being challenged by science.

Bruegel may well have read two works by Erasmus of Rotterdam. In Praise of Folly, published in 1511 is an essay in which Folly praises self-deception and madness before moving on to satirise superstition and corrupt practices in the Catholic Church. Just as pertinent is his Adagia, first published in 1500, a collection of over 3,000 proverbs – suggesting that Erasmus was magnetically drawn to proverbs as Bruegel was. Both men were drawn to the ambiguous nature of proverbs – how open they are to varied interpretation.

But Bruegel’s brilliance was to place the proverbs so firmly in the context of the way of life of the people he lived among. In Painting Life: The Art of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Robert Bonn makes a pretty good case for the majesty of this painting:

In The Netherlandish Proverbs [Bruegel] took a complex culture and enabled us to see its soul, its very essence. […] The genius of it is that when you look at the painting, you experience in one glance the entire essence of Flemish culture in the 16th century.

We are looking at an idealized town square: there’s an inn, stables, workshops and what looks like a castle ruin. A river runs down to the sea in the distance, where a ship sails and a gibbet stands on a sandy spit. In amongst the buildings and the landscape Bruegel has hidden his proverbs in highly imaginative ways.

Take the detail above (from the lower left corner of the painting): it looks like an ordinary street scene at first, with recognisable Flemish characters going about their business. But look closer and we see a woman tying the devil to a pillow (obstinacy overcomes everything) and a man banging his head against a brick wall (trying to achieve the impossible). The latter is just one of many examples that we share with the Dutch, and which are still in common use today.

Sometimes – as in the case of the man banging his head against a brick wall – more than one proverb may be illustrated in the same vignette: in this case, he has one foot shod, the other bare (balance is paramount). On the far left a man is revealed to be a pillar-biter (in other words, a religious hypocrite), while next to him a woman carries fire in one hand and water in the other (she is two-faced and likely to stir up trouble). Meanwhile, behind them both, the sow pulls the bung (negligence is rewarded with disaster).

Remember Brenda Lee singing ‘Let’s Jump the Broomstick’ in 1959? I puzzled over that as an eleven year-old, until I was told it meant, ‘let’s live together without getting married’. In the detail above (from the top left of the painting), the couple kissing in the window are doing just that – marrying under the broomstick. The roof above them is ’tiled with tarts’ (a sign of ostentatious wealth). The chap immediately below them is ‘looking through his fingers’ (turning a blind eye), while below him, the chap with a bare bum seated on the window ledge and reaching for playing cards symbolizes two proverbs: ‘fools get the best cards’ (luck can beat intelligence) and ‘to shit on the world’ (to despise everything).

The man on the tower holding his coat in the breeze symbolizes the proverb to ‘to hang one’s cloak according to the wind’ (he’s adapting his viewpoint to current opinion, or bending with the wind as we would say). The other man to his left is ‘tossing feathers in the wind’ (engaged in a fruitless exercise, or pissing in the wind as we’d say these days). The man below them is ‘gazing at the stork’ (simply wasting his time – a saying that obviously pre-dates bird-watching being accepted as a serious pursuit).

The centre of the picture features various scenes in and around an inn, mostly depicting various ways of wasting time. The man pissing against the inn sign is ‘pissing against the moon’ (pissing in the wind again – wasting time on a futile endeavour). The bandage around his head represents ‘to have a toothache behind the ears’, meaning to be a malingerer. Below him a rather gormless-looking man ‘carries the day out in baskets’ (he’s wasting his time).

Inns are also places that encourage loose talk. The man kneeling before the devil under the blue awning is ‘confessing to the devil (revealing secrets to his enemy), while in the window above a fool is being ‘shaved without lather’ (being tricked) and two fools ‘share one hood’ (because stupidity loves company).

At the top right corner of the detail a man ‘falls from the ox onto the ass’ (he falls on hard times) while behind him another man ‘wipes his backside on the door’ (he’s treating something lightly). He’s also ‘going around shouldering a burden’ (he imagines things are worse than they are).

In this detail, reading from left to right, two men ‘both crap through the same hole’ (they are inseperable comrades); one of them points through a hole in the privy, a reference to ‘anyone can see through an oak plank if there is a hole in it’ (there’s no point in stating the obvious). The elegant man in the fur-lined red cape is ‘throwing his money in the water (he’s wasting it), while the monk behind him ‘throws his cowl over the fence’ (getting rid of something that may come in handy later). To the right a man struggles ‘to hold an eel by the tail’ (he’s performing a difficult task)

In this detail, on the left one man ‘shears sheep while the other shears pigs’ (one has all the advantages, the other has none). The woman in the significantly scarlet dress ‘puts a blue cloak on her husband’ (she deceives him in adultery), while to their left a man ‘casts roses (we would say pearls) before swine’ (wastes his effort on those who aren’t worthy). Meanwhile, in front of them another man is busy ‘filling the well after the calf has drowned’ (closing the stable door after the horse has bolted).

In this last selection (from the lower right of the picture), the man in the white shirt is ‘barely able to stretch from one loaf to another’ (he can’t make ends meet). Another man has ‘spilt his porridge and can’t scrape it up again’ (what’s done can’t be undone: no use crying over spilt milk). The two men behind are ‘pulling to get the longest end’ (trying to gain the advantage). The smart young fellow wearing a cape and with a feather in his cap has ‘the world spinning on his thumb’ (he has every advantage) but someone has put a spoke in his wheel (thwarted his plans).

I’ll conclude with another paragraph from Robert Bonn’s homage to Bruegel, Painting Life in which he argues that the meanings conveyed in this masterpiece transcend both its time and the place where it was painted:

The Netherlandish Proverbs is no simple, quaint genre piece that informs us of life in the lowlands of Europe in the 16th century. Rather, its complexity and its rich detail allow us to see the successes and failures, the struggles and follies of everyday life as people experience it. Indeed, the more you examine the painting, the more you realise the extent to which this marvellous work of art shows an extraordinary grasp of the soul of a culture, the essence of our social life.

See also

- See all the posts about paintings by Bruegel that we have seen in Madrid, London, Brussels, Antwerp, Berlin and Vienna here

There are some brilliant explanations of The Netherlandish Proverbs on the web, using to the full the interactive capabilities of the medium:

- Bruegel, The Dutch Proverbs: Khan Academy video and commentary

- The Netherlandish Proverbs: zoom into details with annotations

- Interactive version of The Netherlandish Proverbs: brilliant rendition of the painting’s details with annotations made by Analog

Reblogged this on Jane Crathern's OCA Practice of Painting Log.

Brilliant post. Will never look at a Bruegel painting in quite the same way again.

Really enjoyed this post with all its insights.

Thanks, Jane, Jean and Peter – comments like yours are really appreciated and make this endeavour worthwhile.

I appreciate your detailed and insightful post.

Votre travail est extraordinaire et très apprécié. Merci.

Merci, Guy.

This is the first time I see this painting. My immediate thought is that the apes could represent us humans.

The chain is central in the picture, so that must mean something. There are two ways out from the place. But the chain disallows both of them. One monkey, the one that is hunching, has realised the truth and has given up. While the other one still hasn’t come to the conclusion.

So, to me the painting says “Whatever way you choose, you are still trapped to where you started. There’s no getting away.”