Lucinda Williams: Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone

Today’s post celebrates a career masterpiece from Lucinda Williams, purveyor of country-soul, rock’n’roll blues – call it what you will – who for the past thirty years has been writing passionate and fiercely confessional songs rich in flawed and broken characters and rooted in the landscape of the American South. I’ll also trace connections between the album and two photographers whose images also portray in intimate detail the landscapes and people of the South.

Lucinda Williams first came to my attention in 1988 when Rough Trade released her eponymous second album of original songs (actually, her third collection, but the first to get any attention over here). Mixing country, blues, and folk and with a voice all heartache, Lucinda Williams defiantly proclaimed – in the words of one of its stand-out songs – ‘Am I too blue for you?’ Another album highlight was ‘Passionate Kisses’ in which Williams sang that she ‘shouted out to the night’:

Give me what I deserve, ’cause it’s my right!

Shouldn’t I have this,

Shouldn’t I have all of this, and

Passionate kisses?

Through seven succeeding studio albums Williams continued to record songs of broken relationships and tragic loss, many apparently drawn from episodes in her own life: songs of grief and joy in which she fearlessly exposed herself in moments of rage, excess and self-disgust. Triumphant albums such as Sweet Old World, Car Wheels on a Gravel Road, Essence and World Without Tears were filled with stark responses to flawed men and failed love affairs. Who could forget the startling image, from ‘Ventura’ from World Without Tears of the singer as she ‘lean[s] over the toilet bowl’ and ‘throws up [her] confession’?

Those early albums were chock-full with brutally honest songs of sorrow and grief in the face of personal tragedy, the death or the suicide of a close friend. Sweet Old World opened with two such songs. One of them, ‘Pineola’, was stark and got straight to the point:

When Daddy told me what happened

I couldn’t believe what he just said

Sonny shot himself with a 44

And they found him lyin’ on his bed

I could not speak a single word

No tears streamed down my face

I just sat there on the living room couch

Starin’ off into space

Mama and Daddy went over to the house

To see what had to be done

They took the sheets off of the bed

And they went to call someone

Both songs were about Frank Sanford, a poet Williams knew in Austin who committed suicide in the early 1990s. Lucinda Williams’ albums have never been uniformly dark, though neither have they constituted light listening. But the payback for spending time with them has always been her defiant search for meaning and her assertion that it is possible to transcend the sorrow in our lives.

Lucinda Williams

Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone is a double album of 20 songs, nearly all of them classics, delivered by a 61-year old woman recharged and at the height of her creative powers. This is Williams’ most expansive collection, not just in terms of length and number of songs, but in two other senses as well. In many of these songs the personal becomes angrily political, while nearly all are allowed to develop over five or six minutes, allowing the excellent roster of assembled players the space to create a a rich musical backdrop for the singer’s spare lyrics. As Paul Rice observed in his review for Slant magazine:

There’s poetry in music, but it’s never found in words alone. Perhaps no living artist exemplifies this better than Lucinda Williams: She isn’t a poet, and her lyrics are often sparse almost to the point of cliché, but she enlivens them with the specificity of her vocal delivery. Her range is limited, but she uses her voice’s eccentricities to maximum emotional effect.

Lucinda Williams isn’t a poet – but her father is, and for the first time she has adapted one of his poems as the album’s opener. Miller Williams is a poet, translator and editor of some renown in the States with over thirty books to his name. He recently retired from teaching at the University of Arkansas, and is perhaps best known for reading his poem ‘Of History and Hope’ at Bill Clinton’s second inauguration.

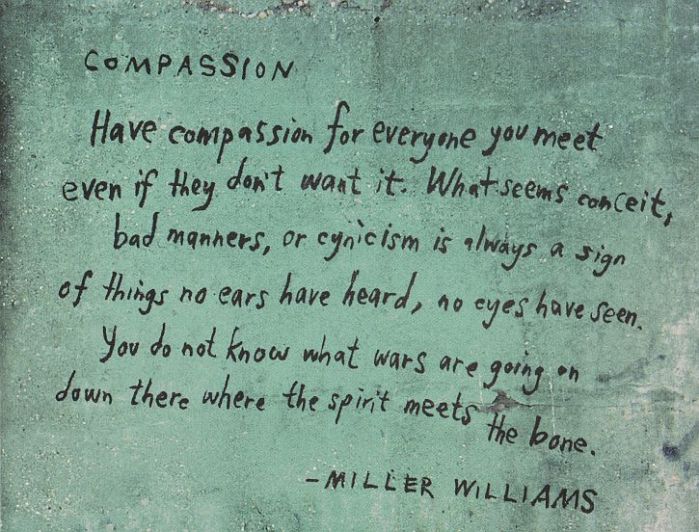

‘Compassion’ by Miller Williams

For the opening track, Lucinda has chosen to perform her father’s poem ‘Compassion’, playing it solo – just vocal and her acoustic guitar. ‘You do not know what wars are going on/Down there where the spirit meets the bone,’ she sings, her voice as rough as sandpaper. It makes an interesting case study of the difference between poetry and song: Lucinda repeats key line’s from her father’s poem – ‘Always a sign’ and ‘Down where the spirit meets the bone’ – to build the rhythm that a song needs. This is her father’s poem on the page:

Have compassion for everyone you meet,

even if they don’t want it. What seems conceit,

bad manners, or cynicism is always a sign

of things no ears have heard, no eyes have seen.

You do not know what wars are going on

down there where the spirit meets the bone.

The rest of the album doesn’t sound like this track at all, but its moral imperative – the importance of empathy – surfaces again and again in subsequent lyrics.

After this, the band kicks into a Tom Petty-style rocker, ‘Protection’, with Williams’ short-to-the-point lyric propelled forward by the driving guitars of Greg Leisz and the Wallflowers’ Stuart Mathis. ‘Living in a world full of endless troubles, where darkness doubles’, Williams sings, she needs protection – from the enemies of love, goodness, kindness, rock’n’roll. And then the punchline:

But my burden is lifted when I stand up

And use the gift I was given for not giving up

The backing musicians on this album are superb – they include Pete Thomas and Davey Faragher of Elvis Costello’s Imposters, Southern soul legend Tony Joe White, jazz guitarist Bill Frisell, Faces keyboardist Ian McLagan, and and Jakob Dylan all making appearances, alongside regulars Greg Leisz, Jonathan Wilson, Pete Thomas and Davey Faragaher.

Another song of simple, yet powerful, repetitions is ‘Foolishness’ on which Williams rails against ‘All of this foolishness in my life’. Against relentlessly pulsing piano, bass and electric guitar that eventually builds to a crescendo, the singer rejects all the fear-monger and liars ‘talking trash and offering pie in the sky’ she is beset by. She vows to stand her own ground: ‘What I do in my own time/Is none of your business and all of mine’. She could be talking about intrusions into her personal life, but this has the universal feel of, say, Neil Young’s ‘Rockin’ in the Free World’; I sense that she is raging against intolerance, bigotry and the politics of hate.

The joys and sorrows of personal relationships have always been central to Williams’ concerns, and there are certainly songs that pursue that theme on this double set, but she has a lot more to say about the world around her this time. Another fine song which illustrates this is ‘East Side of Town’ in which she identifies with the marginalized, inhabiting the persona of someone living in poverty on the wrong side of the tracks, spitting venom at a politician venturing from the bubble inhabited by politicians these days into an area he can never understand. Although ‘East Side of Town’ was written and recorded before the civil unrest in Ferguson, Missouri the fatal shooting of Michael Brown on August 9, it could be a soundtrack for the violence that reflects a country still divided by prejudice and inequality. And you don’t have to be American to feel the power of the track:

I hear you talk about your millions

And your politics

You wanna crosss the poverty line

And then you wanna come have a look around …

You don’t know what you’re talking about

When you find yourself in my neighbourhood

You can’t wait to get the hell out

You wanna see what it means to suffer

You wanna see what it means to be down …

You got your ideas and your visions

And you say you sympathise

You look but you don’t listen

There’s no empathy in your eyes

You make deals and promises …

On ‘West Memphis’ Williams recounts a real-life story of injustice, singing from the perspective of a falsely accused convict, indicting America’s broken criminal justice system with a simple line: ‘That’s just the way we do things here in West Memphis’.

Recently, in an interview with the American website poets.org, Lucinda’s father said: ‘My poetry and her songs – you could say they both have dirt under the fingernails. In my writing, I try to get down to the nuts and bolts of living, and there’s no question that Lucinda does that, too. Her music is not abstract. There’s real sweat in every song.’

Birney Imes, ‘The Social Inn, Gunnisson’,1989

The dirt and the sweat – so much a feature of earlier albums – can still be found here as Williams extracts some sort of wisdom from the wreckage of failed relationships. On what is perhaps the album’s catchiest number, ‘Burning Bridges’, Lucinda watches as a friend careers toward self-destruction. But this is also an album filled with the strength of hope, the determination to overcome hurt and pain, and the joy of living. She sings of the hard work that’s needed to hold a relationship together on ‘Stand Right By Each Other’, while ‘Stowaway in Your Heart’ is one of her most affecting love songs. ‘Walk On’ addresses a young woman, urging her to recognise that though ‘life is full of heartbreak’, yet ‘it’s never more than you can take’:

You’ll win with a little struggle

‘Cause you’re really not that fragile

So walk on

At the end of the first CD is ‘It’s Gonna Rain’, the loveliest and most fragile song of this collection, full of defeat and resignation. But three songs into the second CD we encounter ‘When I Look at the World’, where Williams sings:

I’ve been locked up, I’ve been shut out

I’ve had some bad dreams,

I’ve been filled with regret

I’ve made a mess of things, I’ve been a total wreck

I’ve been disrespected,been taken for a ride

I’ve been rejected and had my patience tried

‘But then,’ she continues, ‘I look at the world and all its glory – and it’s a different story’.

On ‘Temporary Nature (Of Any Precious Thing)’ Williams notes all of the things that ‘love might cost’, before asserting that love ‘can never live without the pain of loss’. Life’s never fair and it can be rough, she sings, but ‘the temporary nature of any precious thing’ just makes it more precious, ‘but not easier to lose’. The album’s central message of personal responsibility for others is emphasised in ‘Everything But the Truth’ where Williams sings that ‘You got the power to make/this mean old world a better place’

Before you can have a friend

You gotta be one

The album opened with Lucinda’s version of her father’s poem ‘Compassion’; it closes with another cover – a gorgeous ten-minute account of JJ Cale’s ‘Magnolia’. This is exceptional, a slowly-evolving, mesmerising performance in which Williams slows the pace of Cale’s original, her languorous vocal drawing out the depth of longing in Cale’s lyric:

Whippoorwill’s singing

Soft summer breeze

Makes me think of my baby

I left down in New Orleans

Lucinda’s soulful vocal is embroidered with the delicate interplay between the guitars of Greg Leisz and Bill Frisell, drifting and serene.

‘Magnolia’ makes a fine conclusion to an outstanding album – a document in which Lucinda Williams bares her soul to the world, as she has always done. It’s a masterpiece.

Birney Imes, ‘Turks Place, Laflore County’, 1989

The photos on the album cover caught my attention, and reading the small print I learned that they are by Birney Imes, a photographer from Mississippi. The images are from his collection Juke Joint, an iconic masterpiece originally published in 1990 in which Imes documented the vanishing black juke joints of the Mississippi Delta in haunting and evocative photographs. Juke Joint is the same book that provided the cover for Lucinda’s Car Wheels On A Gravel Road (above), a photo that inspired the song ‘2 Kool 2 Be Forgotten’ on that album:

You can’t depend on anything really

There’s no promises there’s no point

There’s no good there’s no bad

In this dirty little joint

No dope smoking no beer sold after 12 o’clock

Rosedale Mississippi Magic City Juke Joint

Mr. Johnson sings over in a corner by the bar

Sold his soul to the devil so he can play guitar

Too cool to be forgotten

Hey hey too cool to be for gotten

Man running thru the grass outside

Says he wants to take up serpents

Says he will drink the deadly thing

And it will not hurt him

House rule no exceptions

No bad language no gambling no fighting

Sorry no credit don’t ask

Bathroom wall reads is God the answer yes:

Too cool to be forgotten

Birney Imes, ‘The Social Inn, Gunnisson’,1989

For Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone, Lucinda returned once again to Imes’ photographs, selecting two for the album cover. She told one interviewer that she ‘really loved the way colours popped’ and thought the idea of juke joints as places where the spirit meets the bone was a perfect fit for the album’s title.

Birney Imes, ‘The Black Gold Club, Durant’, 1989

For more than 20 years Birney Imes roamed the countryside of his native Mississippi photographing the people and places he encountered along the way. Working in both black and white and colour, Imes’ photographs documented juke joints and dilapidated restaurants scattered across the Mississippi landscape.

Birney Imes, ‘Royal Crown Cafe, Boyle, Mississippi’, 1983

One reviewer observed that he introduces the viewer to ‘the characters and locales that linger in the margins of Southern memory and culture.’

Birney Imes, ‘King Club, Glendora, Mississippi’, 1984

‘Sometimes the hair on the back of my neck literally stands up when I enter these places’, Imes once remarked. ‘There are some really rough people in them. But I’ve always believed you should photograph what you’re scared of.’

Birney Imes, ‘Juke Joint’

Imes’ photographs have been collected in three books: Juke Joint, Whispering Pines and Partial to Home, and have been exhibited in solo shows in the United States and Europe. Imes owns the local newspaper in Columbus, Mississippi.

Birney Imes, ‘Emma Byrd’s Place, Marcella’, 1989

In the Afterword to Juke Joint Birney Imes writes:

Growing up white in the segregated South of the 1950s, I was only vaguely aware of another culture, another world that existed in the midst of my own. As a child I saw things out of the corner of my eye, but the question of race was one I never had to face straight on. When my high school was integrated in the late sixties, the veil began to part, and I started to see the richness and diversity of a culture that till then had been hidden from me. When I began photographing six or seven years later, it was in part my wish and my need to overcome this ignorance that helped make my choice of subject an obvious one.

Birney Imes, ‘Blume with T.P., Summer, 1986’

One of the delights of Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone is hearing the guitar of Bill Frisell – and therein lies another connection with a photographer of the South. Some five years ago Frisell released an album with the strange-sounding title, Disfarmer. It had been inspired by the story of Mike Disfarmer a small town eccentric from Heber Springs, Arkansas. (When Lucinda Williams was a child, her father, after teaching at various universities across the South finally settled in Fayetteville, Arkansas, having being appointed to teach at the University of Arkansas.)

Disfarmer is an unusual name – because Mike made it up, changing his name to indicate a rift with both his kin and his agrarian surroundings. He was born Michael Meyer in 1884 and legally changed his name to Disfarmer to disassociate himself from the farming community in which he plied his trade and from his own kinfolk – claiming that a tornado had accidentally blown him onto the Meyer family farm as a baby.

Disfarmer set up a portrait studio in Heber Springs and photographed members of the local community, producing portraits that endowed his subjects with a sense of dignity. His photographs capture the essence of a particular community at a particular time with solemnity and a touching simplicity. After his death in the 1950s the negatives and glass plates recording his portraits were rescued and eventually became widely known: the full story is here.

Disfarmer’s photos were described by Howard Smith in Village Voice as, ‘portraits that are spectacularly profound…visual genius…’ Here is a small selection of his astonishing portraits:

The tunes on Bill Frisell’s album had been commissioned by the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio to accompany a retrospective of the work.

There’s a documentary film about Disfarmer (which I haven’t seen); this is a trailer for it:

There’s also a documentary about Bill Frisell’s Disfarmer project; this is a trailer:

And this is a YouTube clip of examples of Disfarmer’s photographs set to Bill Frisell’s tunes:

See also

- Miller & Lucinda Williams: All in the Family: interesting piece about father and daughter

- Compassion Play: Lucinda Williams Is on the Double (Huffington Post interview)

Excellent post, I met Lucinda a few times when she was hanging around LA in the early 2000’s. She did a couple of impromptu short sets at ‘The King King’, Mike Stinson jammed with her and even borrowed my guitar as I happened to have one with me one of those nights. I just remember her being so down to earth which was refreshing in that LA environment, and her being a Grammy winning recording artist etc. She even developed a small crush on my bandmate at the time and once called my house (my bandmate was also my roommate) and she just happened to be on a tour bus with Neil Young! My pal was out at the time and my mind was blown, but we chatted briefly and she was just the sweetest person. I’m always glad to see her keepin’ on and creating top notch art. Cheers for this one!

Excellent memories, alphastare! I’m pleased that you can confirm the impression – gained only from a quarter-century listening to Lucinda’s albums and seeing her once in concert (around the time of ‘Essence’) – that she is indeed, down to earth. Thanks for reading and taking time to write.

A very refreshing memory and a nice break from the usual LA ego’s that were floating around then.

Cheers!

Great post…thanks for making all these interesting connections. Will look for Juke Joint. Say — do you know if the poem by Miller Williams is in his hand? Really love it and am contemplating a tattoo of same. Would be cool if it were.

Thanks for reading, kit. There’s no info on the album sleeve as to whose handwriting it is. My guess for what it’s worth is that it is either that of a design artist, or it’s Lucinda’s.

Reblogged this on Plastic Alto with Mark Weiss and commented:

i like the way this blogger uses Bill Frisell as a segue from Lucinda Williams review to Mike Disfarmer, with Birney Imes as a step. We got to this buy viewing a 90-minute video of William Least heat Moon, “Blue highways” the same bloger also wrote of