There’s a mystery that surrounds Atkinson Grimshaw, the now-celebrated Victorian painter, whose exhibition ‘Painter of Moonlight’ we saw this week in Harrogate. The mystery is this: can an artist spring, fully-formed, into the limelight?

Most biographies of Grimshaw describe him as being a ‘self taught artist’, but, Frank Milner questions this in his essay in the excellent catalogue accompanying the exhibition:

How was it possible for the self-taught Grimshaw to produce such marvellous, fully-resolved pictures as the 1864-5 group of English Lakeland pre-Raphaelite paintings that includes Nab Scar, its companion picture The Bowder Stone, and Blea Tarn? Or, indeed, only two years later to create the group of Wharfedale paintings … that includes the wonderful Ghyll Beck, Yorkshire, Early Spring [below]?

Grimshaw was born in Leeds in 1836. His father was a policeman and both parents were strict Baptists. One online source states that his mother strongly disapproved of his interest in painting, and on one occasion destroyed all his paints. In 1861, at the age of 24 and to the disconcertion of his parents, he abandoned his job as a clerk for the Great Northern Railway to pursue a career in art. His work was first exhibited in Leeds in 1862: still-life arrangements, constructed in the studio, of flowers, foliage and birds’ nests. However, one of his earliest paintings was A Mossy Glen (below), that seems to reflect the Pre-Raphaelite injunction to ‘go to Nature in all singleness of heart, and walk with her laboriously and trustingly… rejecting nothing and scorning nothing’ (Ruskin).

But this where another issue arises: most of Grimshaw’s ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ paintings seem, pretty clearly, to be based on photographs, rather than being sketched or painted out of doors at the locale. Take, for example, Blea Tarn, First Light (below). It’s evident that Grimshaw based this – and others in the Lake District group – on a photograph by Thomas Ogle of Penrith, who produced photographic views sold as souvenirs in Lake District shops. There is an album of views by Ogle and others in the Grimshaw archive. Ogle’s photograph is shown below for comparison.

Reinforcing the conclusion that Grimshaw often painted from photographs is the fact that his archive contains only one sketchbook – and that with empty pages with additional sketches made by his daughter, Emily.

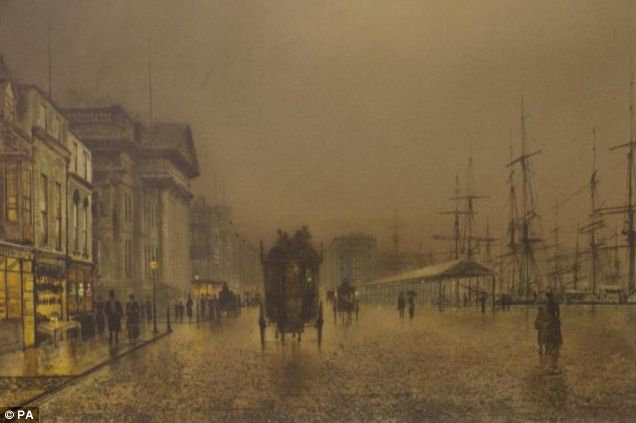

Nevertheless, working in the tradition of the Pre-Raphaelites, Grimshaw’s paintings in this early period demonstrated an attention to detail, and a remarkable skill in painting the effects of light. But he soon began applying these skills to painting city and suburban street scenes and views of the docks in Hull (below), Leeds, Liverpool, and Glasgow.

Unlike the Pre-Raphaelites, Grimshaw painted the modern, urban scene, though his paintings of the Liverpool and Glasgow docks, with their gas lights and brightly-lit shop windows, create a lyrical, romantic mood. His pictures become almost instantly recognisable, with their skilfully-rendered lighting effects, and careful attention to detail. They are paintings of gas-lit streets and misty waterfronts wet with rain and often moonlit. Many are of city street scenes that would have been familiar to Leeds exhibition-goers, such as Leeds Bridge or Boar Lane, Leeds by Lamplight (below).

These were the factors that probably ensured Grimshaw’s success. He had developed a recognisable style and he utilised the same motifs repeatedly. He knew what he could do well, and the public liked it. He became a popular artist in Leeds and in 1865 he was able to move with his wife to a more expensive part of the city. By 1870 Grimshaw was in a position to buy Knostrop Old Hall, a large seventeenth-century manor house, two miles from Leeds. He became particularly successful in the 1870s and was able to afford to rent a second home in Scarborough.

By the 1880s Grimshaw had a studio in Chelsea near James Whistler who was impressed with his moonlit scenes. After a visit to Grimshaw’s studio, Whistler said: ‘I considered myself the inventor of nocturnes until I saw Grimmy’s moonlit pictures’. Grimshaw repaid the compliment by heavily underscoring passages about moonlight, mist and city streets in his copy of Whistler’s book The Gentle Art of Making Enemies which is also on show at the Harrogate exhibition.

At the same time, Grimshaw remained committed to the Leeds art scene: he had campaigned for a Leeds City Art Gallery since it was first suggested by Edmund Bates in 1862, and after a long struggle it was eventually opened in 1888. The Gallery mounted annual spring exhibitions in which Grimshaw was always represented.

I first became aware of Grimshaw after seeing his much-reproduced dockside views of Liverpool, such as Liverpool Docks from Wapping (above). Grimshaw painted this stretch of Liverpool’s Salthouse Dock many times (whether from photographs or from sketches made during visits to the city is unknown). One of his Salthouse Dock views (below) is held by Liverpool Central Library (closed for redevelopment at the moment, but the painting can be viewed on the BBC’s excellent Your Paintings website, currently in development).

Liverpool Docks from Wapping views the dock from the east, while in Liverpool Salthouse Dock (below), originally shown at the Royal Academy of Arts annual summer exhibition in 1885, the dock is viewed from the opposite direction.

Grimshaw was little known outside his native Leeds, but this painting did attract some critical attention. One critic writing in one of the leading art journals of the time praised the way that Grimshaw handled light, capturing the ‘wet, dark streets along which the gas lamps are dimly flickering, and the tall masts of the shipping just visible against the cloud-driven sky: there is a feeling which invests the subject with something akin to poetry’.

Two more paintings of the same stretch of the docks are Liverpool Docks (above) and Liverpool Docks in Moonlight (below).

The Liverpool paintings reflect the regional bias in both Grimshaw’s work and his success. It wasn’t until 1967 that Liverpool Quay by Moonlight (below) became the first Grimshaw to be acquired by the Tate (they now have three). The Tate’s display caption for this work reads:

Grimshaw was famous for his night scenes, in particular for his views of the docks at Liverpool, Glasgow and Hull. Here he concentrates on the golden glow cast from the shop fronts through the fog, and reflected on the wet cobbles. The omnibus receding from the viewer down a perfectly straight street is a characteristic and effective device, which Grimshaw repeated many times in such works. Grimshaw was entirely self-taught, and had begun life as a railway clerk. He was much influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, whose precisely detailed style he initially copied in his landscapes. He gradually moved towards a more ethereal evocation of light and atmosphere somewhat reminiscent of Whistler.

Salthouse Dock, Liverpool (above) was sold for £185,000 in October 2010, having hung in a Northumberland kitchen for five decades after being bought for less than £100. This story reflects collectors’ growing interest in Grimshaw, and the increased popularity of his work with the general public.

Another Liverpool dockside view (above) was painted in 1882. This is similar to two atmospheric London nocturnes, painted around the same time, that are labelled ‘oil on photograph’ in the exhibition, because beneath Grimshaw’s skilfully applied paint are photographs, rather than the more usual artist’s preliminary sketch.

This brings us back to the mystery of Grimshaw’s origins as an artist, and the techniques he employed. Unusually for an artist of this period, Grimshaw left behind no letters or papers and only the one sketchbook, so scholars and critics have little material on which to base an understanding of his life or artistic techniques. Maybe there’s a clue in that railway job he abandoned in order to devote his life to painting. As Frank Milner comments in his catalogue essay:

A rounded view of Grimshaw might one day include a clearer understanding of what he did before he became an artist, while employed by the Great Northern railway.

He wonders whether we might be blinded by a narrow view of what the designation ‘clerk’ might signify: might Grimshaw have been employed in some area of work that was also visual – or photographic?

The exhibition concludes with two small, but exquisite works painted at the very end of his life. Knostrop Cut, Leeds, Sunday Night (1893, below) dates from the last year of Grimshaw’s life, and shows him exploring new colour harmonies. The factory chimneys of Leeds appear as a delicate tracery of lines in the distance.

Snow and Mist: Caprice in Yellow Minor was also painted sometime in the last year of Grimshaw’s life. In her memoir, Grimshaw’s daughter Elaine described how just before he became fatally ill with cancer, her father had continued to experiment with light and colour:

Only the winter before, he had experimented with snow pictures; a farmer trailing homewards across his snowy acres: one could feel the cold, the loneliness with his cattle safe and warm in their byres. We must not trample and mar the crystalline beauty of the snowy paths near the house. He even studied the texture of salt, as we piled it higher in the salt-cellars. Then he turned back to his moonlit wet lanes and streets, painting, painting, painting, all day, pictures to sell now and after he was gone.

Atkinson Grimshaw died on 31st October 1893. There’s another painting from this late period (not in the exhibition) that can be seen as the summation of Grimshaw’s lifetime exploration of the effects of light. Lights on the Mersey (below), executed in 1892, the year before he died, uses a restricted palette and striking economy to depict a vessel against a barely perceptible horizon with sea and sky almost indistinguishable.

This film, made on the occasion of Atkinson Grimshaw: Painter of Moonlight at Mercer Art Gallery in Harrogate, features interviews with Grimshaw’s great-granddaughter April Marsden, biographer Alex Robertson, curator Jane Sellars and contemporary photographer Liza Dracup, who attempt to unpick the story of the man, exploring his tragic family life as well as what inspired him as an artist.

Thank you so much for this – lovely lovely light and colour. I imagine you have a background in the arts in general, judging by your knowledge and how you write.

Those paintings of the Liverpool dockside have brought home to me something I’d not really appreciated before. Despite living in the city for years, the docks have always been ‘hidden’, events taking place out of sight behind the dock wall, or at best ‘somewhere else’. Latterly, containerisation has amplified this ‘invisibility’.

Yet from these paintings, I now see how intimately connected with everyday life the work of the port must once have been. Ships tie up at the quayside; the quays look to be regular thoroughfares; cargo is spilled straight onto the quay from the ship’s hold in sight of the shops from which it probably sold. Must have been a hugely exciting/chaotic experience whenever a laden boat arrived, and intimately embedded in everyday life

“…how intimately connected with everyday life the work of the port must once have been. Ships tie up at the quayside; the quays look to be regular thoroughfares; cargo is spilled straight onto the quay from the ship’s hold in sight of the shops from which it probably sold….”

I’ve wondered about those shop fronts – they look fairly elegant: whether, even though Grimshaw tended to paint from photographs, these scenes are accurate; or whether he enhanced them with glowing shop fronts to intensify the lighting effects. The funny thing is, if you google ‘Liverpool Salthouse dock 19th century images’ you mostly get the Grimshaw views! However, he may be accurate – there are shops visible on some of the dockside images on this page from Colin Wilkinson’s excellent Streets of Liverpool blog: http://streetsofliverpool.co.uk/category/docks/

(BTW: It’s the sadly-lost Custom House that is visible in most of the Grimshaw paintings).

I’ve had an email from Colin Wilkinson who confirms the essential accuracy of Grimshaw’s views:

I know the painting well and although he has ‘livened’ up the scene, it is not too fanciful. The building in the centre (with classical columns) is the Custom House, which at the time was a key government building. The dock road on either side had pubs and other port related buildings (I remember some of them surviving until the early 1970s. In my 1864 Gore’s Directory, there are chandlers, sail-makers, victuallers, refreshment rooms all listed – although none of these would require an elegant frontage. Perhaps the best reference is Herdman’s picture of the Custom House of 1858 – which gives a good perspective of the road with its shops to the left and right. I have attached his picture for your interest.

Regards, Colin

The Herdman picture is here:

http://liverpoolremembrance.weebly.com/uploads/2/9/5/6/2956791/1208137.jpg?502

My goodness, what a magnificent building the Custom House was! And what a colossal loss to the city. Utterly irreplaceable. This website provides a fabulous collection of photographic evidence of both its magnificence and the disaster that befell it.

http://bit.ly/j1xqJB

I’d previously understood that wartime bomb damage had rendered the building beyond salvage. But that appears not to have been the case, at least not unarguably so. It was gutted by firebombs, but the structure remained in good shape. The country was nearly bankrupt in the years immediately following the war. So cash for recovery and restoration would have been scarce; priorities would have needed to be established. Possibly Liverpool was told they’d be cash to restore either the William Brown St buildings or the Custom House, but not cash enough for both. I speculate though because I find it impossible to believe that the authorities of the day would have passed up the chance to preserve it, had the chance been available.

If only…

Would anyone know how one could purchase the new John Atkinson Grimshaw book by Jane Sellars? I live in the U.S. and am finding books on this artist very very difficult to find.I am totally in awe of his work and would love to have a book to reference.He seemed to know something about moonlit skies.thanks.tom

The book is excellent. It is published by the Mercer Art Gallery Harrogate and has disappeared from Amazon.co.uk listings, too. It cost around £20. I can only suggest contacting the gallery to see if they still have copies. Their phone no is: 01423 556188. You can email them by completing the form on this page: http://www.harrogate.gov.uk/pages/harrogate-2415.aspx

Atkinson Grimshaw did alter some of his subjects to get the best composition. For instance, the Custom House in the Salthouse Dock painting was brought forward to line through with the Strand and Wapping, which were themselves shown straight but were angled in plan. Though his painting perfectly captures the noctural scene, it can’t be relied upon for historical accuracy, as say a William Herdman or W.G. Herdman painting can.

Darren

excellent article.I sometimes wonder what it was like ,in all aspects, to have been an artist,struggling or successful in those periods of time. Painting without the comforts that we enjoy today ,at a time when art had just been settling into approachability by the recently minted middle class.thank-you for the research,insights and articulation. tom

Do you know how I can find out if Mr Atkinson Grimshaw ,could be a distant relative, my name was Grimshaw, I lived in Ascot Berkshire. My great grandfather was Henry Grimshaw, born Clitheroe Lancs in 1841, Ellis Grimshaw born 1839,John born 1836, could be brothers? My grandfather was Herbert he lived in Wandsworth ,London when I was a girl. I married an American Airman and now reside in Kansas City, Kansas . My e mail address is audreydapike@gmail.com. I also paint, and my great grandson is showing great promise, thank you for your consideration. Audrey Pike.

In 1973/4 I was a lithographic printer, working in Leeds for a small specialist art reproduction printer called Lautrec Photo Litho, near the Headingly Arena.

Everything was printed by a single colour Mann Fast Three, I had the pleasure of producing a series of six paintings for Scarborough Art Gallery, of Painting By local Artist John Atkinson Grimshaw

From memory these included Silver Moonlight a night scene of Knostrop Hall which the artist had purchased,

Burning Off A seascape of a Fire of a Scarborough sea front building at night, Two views of Liverpool Harbour, one facing East, One facing West, again both night scenes, One of Scarborough Harbour viewed from the base of the lighthouse looking toward the castle. This included having a hazy moon above the Castle, a physical impossibility because the view is due North and one other which was a London dock scene.

These were printed in six colours the usual blue, yellow ,magenta and black plus two subtle grey tints to highlight various points.

I retained a dozen of each prints which became mounted Christmas gifts for my family and friends. I actually

had all the original paintings beside the press during production to ensure I attained the correct results, the smallest was just a little larger than double foolscap in size, Silver Moonlight, and the largest, The Burning off seascape, which was almost the size of an advertising poster some 56 inches by 35 inches.

They were all absolutely beautiful paintings, and I managed to have my prints textured by a company called Dispro, who were print finishers in Leeds. I had some very happy family and friends that Christmas.

I have been happy to see the portraits at various times in The Art Gallery at Scarborough, there is an exhibition of Grimshaws works starting In 2022 for a year at the gallery i would recommend anyone who gets to Scarborough to spend an hour or so to view the exhibition.

HI Steve, I have just picked up a Silver Moonlight Atkinson Grimshaw print in a charity shop in Australia. On the back of the frame it states A product of Lautrec, Leeds. Will this be one of the prints you mentioned you made or did they produce a few? I wondered how it had been made as it looked to be textured. It’s not a small print and it’s in gold frame. I am originally from Bradford and when I saw the picture it reminded me of home.