The other day I posted about how access to the river Mersey was restricted by the Cressington and Grassendale private estates. ‘As a freeborn Englishman’, I wrote, ‘I can’t understand the idea that a private estate should have the right to deny people access to a great river’. That provoked a fair amount of debate, so I thought I’d look at the question of the right of access and the notion of public space in a bit more detail, exploring how the struggle for common land and the right to wander where you will has reflected sharply-differing interpretations of the legal and moral meaning of private property. From the resistance to the enclosure of common lands to the hard-fought struggle for the right to roam, it’s a stirring story, and one that is far from over; new battle-lines are being drawn over access to the British coastline and its beaches, and the rapid privatisation of public space in our cities.

No man made the land, it is the original inheritance of the whole species. The land of every country belongs to the people of that country.

– John Stuart Mill, 1848

When you step back and take a historical view, what is clear is that access to the land has been a defining issue in British society for a thousand years. Rebecca Solnit, a writer thrilled by the extent of the English network of paths and rights of way compared to her native America, has nevertheless observed that in this country ‘accessing the land has been something of a class war’. For a thousand years, landowners have been sequestering more and more of the island for themselves, and for the past hundred and fifty, landless people have been fighting back.

For some, it’s all down to the Normans; conquering England in 1066, they embarked on a swift land grab, establishing huge deer parks for hunting (the nearest here being Toxteth Park and the hunting forest of Mara and Mondrum, now known as Delamere). Fierce penalties for poaching or in any way encroaching upon these hunting lands were visited upon the poor or landless in the centuries that followed – castration, deportation, execution (after 1723, for example, taking rabbits or fish, let alone deer, was an offence punishable by death).

The deer parks were gouged from the commons: lands which might be (usually were) privately owned, but on which locals retained rights to gather wood and graze animals – and to follow their noses. Over time a principle had been established in common law: that the public had the right to walk no matter whose property they traversed, following rights-of-way-footpaths across the fields and woods that were necessary for work and travel.

There’s a proud tradition of English folk rising up to resist the trashing of these entitlements by the rich and powerful, and it stretches back a long way. Between 1509 and 1640 there were more than three hundred riots in England, many of them sparked off by the enclosure of common land or the denial of customary rights of pasture. Some were large enough to be regarded as risings or rebellions; others were small and insignificant, a handful of villagers levelling someone’s hedges and letting their cattle in.

The Norfolk Rising of 1549 began as a local demonstration against the enclosure of common land, but quickly developed into a revolt against the whole system of enclosures. It is considered, after the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, the most significant of all the peasant risings. In an organized response to the general oppression of the poor, 16,000 rebels attacked and took possession of Norwich, then the second city of the kingdom, and for three weeks administered the district until attacked and defeated by a government army. This is how a chronicler at the time reported the sense of injustice felt by those who rose up:

For, said they, the pride of great men is now intolerable, but their condition miserable. These abound in delights and compassed with the fullness of all things, and consumed with vain pleasure, thirst only after gain, and are inflamed with the burning delights of their desires: but themselves almost killed with labour and watching, do nothing all their life long but sweat, mourn, hunger and thirst . . .

The common pastures left by our predecessors for the relief of us and our children are taken away. The lands which in the memory of our fathers were common, those are ditched and hedged in, and made several. The pastures are enclosed, and we shut out: whatsoever fowls of the air, or fishes of the water, and increase of the earth, all these they devour, consume and swallow up; yea, nature doth not suffice to satisfy their lusts …

Shall they, as they have brought hedges against common pastures, inclose with their intolerable lusts also, all the commodities and pleasure of this life, which Nature the parent of us all, would have common, and bringeth forth every day for us, as well as for them? We can no longer bear so much, so great and so cruel injury, neither can we with quiet minds behold so great covetousness, excess and pride of the nobility; we will rather take arms, and mix heaven and earth together, than endure so great cruelty. Nature hath provided for us, as well as for them; hath given us a body and a soul, and hath not envied us other things. While we have the same form, and the same condition of birth together with them, why should they have a life so unlike to ours, and differ so far from us in calling?

We desire liberty, and an indifferent [equal] use of all things: this we will have, otherwise these tumults and our lives shall end together.

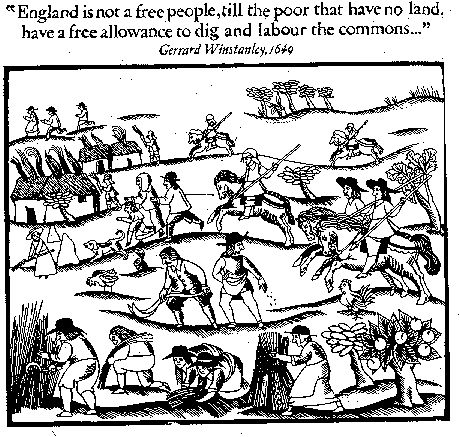

In the Putney debates of 1647, the Leveller Colonel Rainborough argued that, ‘the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live as the richest he’; two years later, on 1 April 1649, Gerrard Winstanley (who hailed from Wigan) and his fellow diggers started cultivating land on St George’s Hill, Surrey, and proclaimed a free Commonwealth.

We come in peace, they said

To dig and sow

We come to work the land in common

And to make the waste land grow

This earth divided

We will make whole

So it can be

A common treasury for all.

The sin of property

We do disdain

No one has any right to buy and sell

The earth for private gain

By theft and murder

They took the land

Now everywhere the walls

Rise up at their command.

– Leon Rosselson, ‘World Turned Upside Down’

In their first manifesto the Diggers asserted:

The earth (which was made to be a Common Treasury of relief for all, both Beasts and Men) was hedged into Inclosures by the teachers and rulers, and the others were made Servants and Slaves. … Take note that England is not a Free people, till the Poor that have no Land, have a free allowance to dig and labour the Commons, and so live as Comfortably as the Landlords that live in their Inclosures.

As well as joining in the collective labour on the occupied land at St Georges Hill, Winstanley wrote pamphlets defending the Diggers’ cause. This was not just a local matter, but a national issue. The traditional village was breaking up under the pressures of an emerging capitalist market. Richer farmers were beginning to produce for the market, employing the labour of villagers who had been evicted from their smallholdings and become dependent on wages. Yet, Winstanley (whose proto-socialist argument was couched in religious terms, as most debates were at the time) pointed out, one third of England was uncultivated wasteland – barren while children starved:

Let all men say what they will, so long as such are Rulers as call the Land theirs, upholding this particular propriety of Mine and Thine; the common-people shall never have their liberty, nor the Land ever [be] freed from troubles, oppressions and complainings. O thou proud selfish governing Adam, in this land called England! Know that the cries of the poor, whom thou layeth heavy oppressions upon, is heard. […]

Therefore you dust of the earth, that are trod under foot, you poor people, that makes both scholars and rich men your oppressors by your labours, take notice of your privilege, the Law of Righteousnesse is now declared. All the men and women in England, are all children of this Land, and the earth is the Lord’s, not particular men’s that claims a proper interest in it above others, which is the devil’s power. This is my Land …

Therefore if the rich will still hold fast this propriety of Mine and Thine, let them labour their own land with their own hands. And let the common-people … labour together, and eat bread together upon the Commons, Mountains, and Hills. For as the enclosures are called such a man’s Land, and such a man’s Land; so the Commons and Heath, are called the common-people’s, and let the world see who labours the earth in righteousnesse, and . . . let them be the people that shall inherit the earth. …Was the earth made for to preserve a few covetous, proud men, to live at ease, and for them to bag and barn up the treasures of the earth from others, that they might beg or starve in a fruitful Land, or was it made to preserve all her children?

The Diggers’ occupation of the land on St Georges Hill lasted only five months before they local landowners went to court to have them evicted. In 1649, St George’s Hill was a stretch of wasteland. Today, ironically, it is an exclusive gated private estate, with multi-million pound mansions, golf course and private tennis courts. In 1995 and 1999 The Land is Ours, the group founded by George Monbiot, organised a mass trespass there in order to dramatise the issues of open access to the countryside of how the land is used.

In Scotland, common land was abolished in 1695, while in England enclosure acts and unauthorized but fiercely enforced seizures of hitherto common land accelerated in the eighteenth century. Between 1760 and 1870, about 7 million acres (about one sixth the area of England) were changed by Acts of Parliament from common land to enclosed land. In Das Kapital, Marx described how, from the 15th century to 19th century, ‘the systematic theft of communal property was of great assistance in swelling large farms and in ‘setting free’ the agricultural population as a proletariat for the needs of industry’.

Many did indeed see the process as a war; in 1803, the President of the Board of Agriculture, writing at the height of the Napoleonic Wars, saw the colonization of the commons around London as a patriotic duty:

Let us not be satisfied with the liberation of Egypt or the subjugation of Malta, but let us subdue Finchley Common, let us conquer Hounslow Heath; let us compel Epping Forest to submit to the yoke of improvement.

North of the border, in the Clearances, thousands of Highlanders were evicted from their holdings and shipped off to Canada, or forced to seek work as wage labourers in the industrial towns as landowners turned their estates over to profitable sheep farming. Some cottagers were literally burnt out of house and home by the agents of the Lairds. Betsy Mackay, who was sixteen when her family was evicted from the Duke of Sutherland’s estates, gave this account of their eviction:

Our family was very reluctant to leave and stayed for some time, but the burning party came round and set fire to our house at both ends, reducing to ashes whatever remained within the walls. The people had to escape for their lives, some of them losing all their clothes except what they had on their back. The people were told they could go where they liked, provided they did not encumber the land that was by rights their own. The people were driven away like dogs.

In England, as E.P. Thompson wrote in The Making of the English Working Class,’the years between 1760 and 1820 are the years of wholesale enclosure in which, in village after village, common rights are lost. … Enclosure (when all the sophistications are allowed for) was a plain enough case of class robbery’. In 1809, when John Clare was 16, an Enclosure Act was passed to enclose lands in the parish of Helpstone in Northamptonshire and in neighbouring parishes. This was the land where he had been raised, and it formed his world, his horizon:

Nor fence of ownership crept in between

To hide the prospect of the following eye

Its only bondage was the circling sky

– John Clare, from The Moors, 1824

The central aim of enclosure was to increase profits, but the price of ‘Improvement’ was the loss of the commons and waste grounds, which according to the Act ‘yield but little Profit’:

Now this sweet vision of my boyish hours

Free as spring clouds and wild as summer flowers

Is faded all – a hope that blossomed free,

And hath been once, no more shall ever be

Inclosure came and trampled on the grave

Of labour’s rights and left the poor a slave

And memory’s pride ere want to wealth did bow

Is both the shadow and the substance now

– John Clare, from The Moors, 1824

Clare was devastated by this violation of his natural and social environment. For Clare, the open-field system fostered a sense of community, the fields spread out in a wheel with the village at its hub. Fences, gates and ‘no trespassing’ signs went up. Trees were felled and streams diverted so that ditches could follow a straight line:

There once was lanes in natures freedom dropt

There once was paths that every valley wound

Inclosure came & every path was stopt

Each tyrant fixt his sign where pads was found

To hint a trespass now who crossd the ground

Justice is made to speak as they command

The high road now must be each stinted bound

–Inclosure thourt a curse upon the land

& tastless was the wretch who thy existence pland

– John Clare, from ‘The Village Minstrel’, 1821

George Monbiot, writing in The Guardian in July 2012, observed how, as Clare moved from his teens to his thirties, acts of enclosure granted the local landowners permission to fence the fields, the heaths and woods, excluding the people who had worked and played in them. For Clare, everything he sees falls apart:

Almost everything Clare loved was torn away. The ancient trees were felled, the scrub and furze were cleared, the rivers were canalised, the marshes drained, the natural curves of the land straightened and squared. Farming became more profitable, but many of the people of Helpston – especially those who depended on the commons for their survival – were deprived of their living. The places in which the people held their ceremonies and celebrated the passing of the seasons were fenced off. The community, like the land, was parcelled up, rationalised, atomised. I have watched the same process breaking up the Maasai of east Africa. […]

What Clare suffered was the fate of indigenous peoples torn from their land and belonging everywhere. His identity crisis, descent into mental agony and alcohol abuse, are familiar blights in reservations and outback shanties the world over. His loss was surely enough to drive almost anyone mad; our loss surely enough to drive us all a little mad.

For while economic rationalisation and growth have helped to deliver us from a remarkable range of ills, they have also torn us from our moorings, atomised and alienated us, sent us out, each in his different way, to seek our own identities. We have gained unimagined freedoms, we have lost unimagined freedoms – a paradox Clare explores in his wonderful poem ‘The Fallen Elm‘. Our environmental crisis could be said to have begun with the enclosures. The current era of greed, privatisation and the seizure of public assets was foreshadowed by them: they prepared the soil for these toxic crops.

In John Clare: A Biography, Jonathan Bate follows E.P. Thompson in describing Clare as a poet of ‘ecological protest’, a political poet angered by the destruction of ‘an ancient birthright based on co-operation and common rights’:

These paths are stopt – the rude philistine’s thrall

Is laid upon them and destroyed them all

Each little tyrant with his little sign

Shows where man claims earth glows no more divine

But paths to freedom and to childhood dear

A board sticks up to notice ‘no road here’

And on the tree with ivy overhung

The hated sign by vulgar taste is hung

As tho’ the very birds should learn to know

When they go there they must no further go

Thus, with the poor, scared freedom bade goodbye

And much they feel it in the smothered sigh

And birds and trees and flowers without a name

All sighed when lawless law’s enclosure came

And dreams of plunder in such rebel schemes

Have found too truly that they were but dreams.

– John Clare, from The Moors, 1824

As I went walking I saw a sign there

And on the sign it said ‘No Trespassing’

But on the other side it didn’t say nothing,

That side was made for you and me.

– Woody Guthrie, ‘This Land Is Your Land’

When Britain was still a rural economy of land workers, the struggle over access to the land was about economics, about survival. But by the middle of the nineteenth century, half the nation’s population lived in cities and towns. It was in this period that the conflict over common land and rights of way changed from being about economic survival and became – as Rebecca Solnit puts it in Wanderlust – about ‘psychic survival, about a reprieve from the city’. As more and more people chose to spend their spare time walking, more and more of the traditional rights of way were closed to them. The issue became the right to roam.

You can date the desire to roam freely in the countryside back to the Romantic poets. Rebecca Solnit tells the story of a confrontation at Lowther Castle in Cumbria, where Wordsworth was being entertained by the Earl of Lonsdale. At dinner, the earl complained that his wall had been broken down and that he would have horsewhipped the man who did it. At the end of the table, Wordsworth heard the words, the fire flashed into his face and rising to his feet, he answered: ‘I broke your wall down, Sir John, it was obstructing an ancient right of way, and I will do it again.’

Solnit is a great admirer of the English tradition of establishing, and fighting to hold onto, rights of way:

Certainly one of the pleasures of walking in England is this sense of cohabitation right-of-way paths create – of crossing stiles into sheep fields and skirting the edges of crops on land that is both utilitarian and aesthetic. American land, without such rights-of-way, is rigidly divided into production and pleasure zones, which may be one of the reasons why there is little appreciation for or awareness of the immense agricultural expanses of the country. British rights of way are not impressive compared to those of other European countries – Denmark, Holland, Sweden, Spain – where citizens retain much wider rights of access to open space. But rights-of-way do preserve an alternate vision of the land in which ownership doesn’t necessarily convey absolute rights and paths are as significant a principle as boundaries.

Nearly 90 percent of Britain is privately owned, but Solnit expresses her admiration for ‘a culture in which tresspassing is a mass movement and the extent of property rights is open to question’. The movement that fought – and continues to fight – for unfettered access to land and shore began in the late 19th century. The Liberal MP James Bryce, who introduced an unsuccessful bill to allow access to privately held moors and mountains in 1884, declared a few years later:

Land is not property for our unlimited and unqualified use. Land is necessary so that we may live upon it and from it, and that people may enjoy it in a variety of ways. and I deny therefore, that there exists or is recognized by our law or in natural justice, such a thing as an unlimited power of exclusion.

Today, campaigns for footpaths and the right to roam may have support from people of all social backgrounds, but at the dawn of the 20th century, the issue was seen in class terms and became a significant strand in the socialist movement. In 1900 the Sheffield Clarion Ramblers -a socialist organisation – was formed, followed in 1907 by the Manchester Rambling Club. In 1928 the nationwide British Workers Sports Federation and in 1930 the Youth Hostels Association began to provide lodging for young hikers and working class walkers with limited means. Historian Raphael Samuels observed that, ‘hiking was a major, if unofficial, component of the socialist lifestyle’. By the 1920s and 1930s, tens of thousands of workers spent their Sundays walking; in 1932, some 15,000 headed for the hills from Manchester alone each weekend. But they found their access blocked by rich landowners.

Kinder Scout, the highest and wildest point in the Peak District, became the focus of the most famous battle for access. It had been public land until 1836, when an enclosure act divided the land up among the adjacent landowners, giving the lion’s share to the Duke of Devonshire, owner of Chatsworth House. The fifteen square miles of Kinder Scout became completely inaccessible to the public. Walkers called it ‘the forbidden mountain’.

In April 1932, over 400 people participated in a mass trespass onto Kinder Scout. The event was organised by the Manchester branch of the British Workers Sports Federation. Walkers encountered gamekeepers with clubs and police with truncheons (above) during the mass trespass, and five men from Manchester, including the leader, Benny Rothman, were subsequently jailed. One of Ewan MacColl’s greatest songs, ‘Manchester Rambler’, was written in celebration of the Kinder trespass:

I’m a rambler, I’m a rambler from Manchester way

I get all me pleasure the hard moorland way

I may be a wage slave on Monday

But I am a free man on Sunday

I’ve been over Snowdon, I’ve slept upon Crowden

I’ve camped by the Waine Stones as well

I’ve sunbathed on Kinder, been burned to a cinder

And many more things I can tell

My rucksack has oft been me pillow

The heather has oft been me bed

And sooner than part from the mountains

I think I would rather be dead

The day was just ending and I was descending

Down Grindsbrook just by Upper Tor

When a voice cried ‘Eh you’ in the way keepers do

He’d the worst face that ever I saw

The things that he said were unpleasant

In the teeth of his fury I said

‘Sooner than part from the mountains

I think I would rather be dead’.

He called me a louse and said ‘Think of the grouse’

Well I thought, but I still couldn’t see

Why all Kinder Scout and the moors roundabout

Couldn’t take both the poor grouse and me

He said ‘All this land is my master’s’

At that I stood shaking my head

No man has the right to own mountains

Any more than the deep ocean bed

So I walk where I will over mountain and hill

And I lie where the bracken is deep

I belong to the mountains, the clear-running fountains

Where the grey rocks rise rugged and steep

I’ve seen the white hare in the gulley

And the curlew fly high over head

And sooner than part from the mountains

I think I would rather be dead

On its 75th anniversary, the trespass was described by Roy Hattersley as, ‘the most successful direct action in British history’ because, just over a decade later, it achieved a result. The Ramblers’ Association had started its own right-to-roam campaign in 1935 and in 1945, within days of taking office, the Attlee Labour government set up a series of official committees which recommended establishing a system of national parks and establishing the right to roam across all open and uncultivated land. Ten national parks were created but the only access improvement achieved was to strengthen the existing system of public footpaths.

In Finland, Norway and Sweden, the right to walk where you wish is enshrined in the principle of allemansrätt, or ‘every man’s right’. In Sweden, allemansrätt, guaranteed in the national constitution, is considered a central tenet of the national approach to tolerance, its origins stretching back in part to medieval provincial laws and customs. In Scotland the Land Reform Act 2003 grants an extensive right to roam almost anywhere, as long as it is exercised responsibly. But England has always lagged behind.

On the fiftieth anniversary of its creation, the Ramblers’ Association began holding ‘Forbidden Britain’ mass trespasses of its own and in the 1997 election the Labour party promised to support ‘right to roam’ legislation that would at last open the countryside to the citizens. More radical new groups such as This Land Is Ours (founded by George Monbiot) began to take direct action to highlight a situation in which just 6,000 landowners, mostly aristocrats, own about 40 million acres – or two thirds of the land in the UK – over which public access was largely prohibited. But, increasingly it’s not just about aristocrats: since the 1980s the trend has been towards land being bought up by multinational corporations and financial institutions.

Marion Shoard, author of A Right to Roam (1999) has written that ‘underlying successive skirmishes between owners and landless has been a simmering war of competing ideologies in which the supposed right of ownership of the environment has come up against a growing sense that the earth belongs in some sense to all’.

In A Right to Roam, Shoard wrote:

Seventy-seven per cent of the UK’s land is countryside, and this still includes much magnificent scenery. Yet the increasing numbers of people setting off in search of it find their simple quest ends all too often in disappointment and frustration. They can visit the ever more crowded country parks, picnic areas, and other enclaves provided by public and voluntary bodies, but if they try to venture beyond such places and roam freely they soon run up against a harsh reality. Most of Britain’s countryside is forbidden to Britain’s people. They may look at it through their car windscreens but they may not enter it without somebody else’s permission – permission which will be withheld more often than not. The rural heritage they may have loved unthinkingly since childhood turns out to be locked away from them behind fences, walls, and barbed wire. Where they have been expecting relaxation and peace they find instead warnings to keep out and threats of prosecution.

Our law of trespass holds us in its grim thrall throughout our country. Most of us are vaguely aware that those omnipresent ‘Trespassers will be Prosecuted’ signs are partly bluff. But all of us also know that trespass is indeed illegal, whether or not our wanderings are likely to put us in the dock. When an owner or his representative confronts us, we do not usually choose to argue the toss with him about our right to walk in our countryside. If we did, we should lose the argument. He has the right to use force to remove us. As a result, more than 90 per cent of woodland in Oxfordshire, for example, is effectively out of bounds to the walker. […]

Of course no one challenges today the idea of private property. But other societies hesitate to regard the land itself as something that can be owned as absolutely as a piece of jewellery. Our own laws of compulsory purchase and development control implicitly challenge this idea. Deep down we all know it is wrong. Throughout human history, the notion of which of the planet’s resources might reasonably be held as property by individuals has changed as different peoples at different times have developed different ideas of what is right.

In 2000 the Labour government of Tony Blair introduced legislation that established a limited right to roam over mountain, moorland, heath and downland. The bill was passed in the teeth of opposition from landowners (and from the Prime Minister himself, who backed landowners’ calls for voluntary arrangements instead of a public right). Members of the House of Lords called the bill ‘an attack on property and the rights of ownership’ and ‘a travesty of justice’, and warned that it would lead to drug parties, devil worship and supermarket trolleys in Britain’s wild places. Implementation of the Act was completed in 2005, but it didn’t grant a Scottish or Scandinavian-style right to walk anywhere you like, limiting access on foot to 936,000 hectares of mapped, open, uncultivated countryside.

All of this raises the question: Who owns Britain? Some answers are provided in figures from a surprising source. In 2o10, Country Life Magazine published ‘Who Owns Britain?’, thought to be the most extensive survey of its type undertaken since 1872. The findings were revealed via another unlikely source: the Daily Mail:

The top private landowner, not just in Britain but Europe, is the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensbury, whose four sumptuous estates cover 240,000 acres in England and Scotland. But while his land is the most vast, it is not the most valuable, as the net worth depends on how much is farmland, as well as the value of the property and sporting and heritage activities on it.

The most valuable land belongs to Number 4 on the list, the Duke of Westminster, whose Grosvenor Estate, worth a whopping £6 billion, takes in the wealthiest areas of London, including Belgravia and Mayfair [and, I might add, a sizeable chunk of central Liverpool – more about that in a ‘mo].

Simon Fairlie writing in Land magazine highlights the undemocratic and increasingly unequal pattern of land ownership:

Over the course of a few hundred years, much of Britain’s land has been privatized — that is to say taken out of some form of collective ownership and management and handed over to individuals. Currently, in our ‘property-owning democracy’, nearly half the country is owned by 40,000 land millionaires, or 0.06 per cent of the population, while most of the rest of us spend half our working lives paying off the debt on a patch of land barely large enough to accommodate a dwelling and a washing line.

Yet the individual millionaires are now dwarfed by the incredible reach of corporate land-ownership, which barely existed 100 years ago. As the biggest 19th-century landowners such as the Church have been sidelined by economic and social changes, their land has been snapped up by the private sector. Pension Funds own 550,000 acres. Catching up swiftly are foreign investors and even supermarkets. Waitrose owns a 4,000-acre estate in Hampshire, which it runs as a farm, while Tesco’s 2,545 stores alone take up 770 acres.

During the 18th and 19th century, before the advent of local government, the enclosures parcelled up so much of the countryside for country landowners that, according to today’s estimates, only 4% of land in England and Wales is registered as ‘commons’.

And it’s not just the countryside: in the last few decades the enclosures have moved into our towns and cities. Large sections of cities such as London, have long been owned by a small group of wealthy landlords. For example, the Duke of Westminster owned the whole of northern Mayfair, Belgravia and Pimlico, the Duke of Bedford owned Covent Garden while the Earl of Southampton owned the Bloomsbury Estate.

But, generally speaking, for much of the 20th century the ownership and management of property in cities has been in the hands of a diverse patchwork of private landlords, institutions, local government and private individuals. In the last few decades, however, city centre regeneration, especially in declining industrial areas has often taken the form of very large new developments owned and managed by a single private landlord. In Liverpool, the city council handed a single private landlord, Grosvenor Estates, 42.5 acres of land extending over 34 streets for redevelopment on a 250-year lease. This is Liverpool One – a highly successful retail development that has contributed to the resurgence of the city – but one of a type that raises concerns about the erosion of public space in our cities.

It began with Canary Wharf and Liverpool One; now many commentators are drawing attention to a creeping privatisation of public space. Streets and open spaces are being defined as private land after redevelopment. There are now privatised public spaces in towns and cities across Britain.

In the past decade, large parts of Britain’s cities have been redeveloped as privately-owned estates, extending corporate control over some of the country’s busiest squares and thoroughfares. These developments are no longer enclosed shopping malls; they retain much of the old street pattern, spaces open to the sky, and appear to be entirely public to casual passers-by. But the land is private, and members of the public enter the area subject to rules and restrictions set by the developers – and enforced by their own security personnel.

The writer who has done most to map this process is Anna Minton, author of Ground Control. In her book, Minton explains that the current wave of land privatisation started in the 1980s, with the development of Canary Wharf. New Labour gave the process a boost in 2004 when it changed the legal basis by which Compulsory Purchase Orders were assessed. Previously they had to show they were in the public interest; now they need only to demonstrate ‘economic interest’.

The opportunity to reconstruct urban space so radically, Anna Minton argues, was created by the de-industrialisation of the city, and the closure of the factories, works, warehouses and docks which used to dominate the urban landscape. What we’re seeing as a result is a rapid reversal of the long trend through the 19th century by which roads and highways were ‘adopted’ by the local authority. Minton calls this ‘the creeping privatisation of the British public realm’.

From Liverpool One to Cabot Circus in Bristol, privately owned and privately controlled places, policed by security guards and featuring round the clock surveillance, came to define our cities. In London, Westfield Stratford City and the Olympic Park represent the latest stage of this process, based on property finance and retail, and underpinned by large amounts of debt.

The subtitle of Anna Minton’s book is ‘Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-First Century City’. She explains how urban space is increasingly owned by private corporations and watched over by CCTV as developers fear disruption, crime, filth, and chaos. The result, she argues, are standardized urban spaces that look and feel alike wherever they arise: spaces that are impersonal, anonymous, hostile and not inclusive. There are rules and security guards to police them: no music, no busking, no picnics, no alcohol, no photography, no street theatre, no ball games, no skateboarding, no roller-blading, no cycling. And, above all, no protests. Surveillance is widespread, usually via CCTV. ‘The streets’, says Minton, ‘have been privatised without anyone noticing’.

In Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit, drew a bead on the political aspect of this enclosure of once open and public urban spaces. Writing about her native San Francisco, and its tradition of parades and protests, she wrote:

This is the highest ideal of democracy – that everyone can participate in making their own life and the life of the community – and the street is democracy’s greatest arena, the place where ordinary people can speak, unsegregated by walls, unmediated by those with more power. It’s not a coincidence that media and mediate have the same root; direct political action in real public space may be the only way to engage in unmediated communication with strangers, as well as a way to reach media audiences by literally making news. ….. Parades, demonstrations, protests, uprisings and urban revolutions are all about members of the public moving through public space for expressive and political rather than merely practical reasons.

Paul Kingsnorth writing in his book Real England, put it another way:

It is the essence of public freedom: a place to rally, to protest, to sit and contemplate, to smoke or talk or watch the stars. No matter what happens in the shops and cafes, the offices and houses, the existence of public space means there is always somewhere to go to express yourself or simply to escape. … From parks to pedestrian streets, squares to market places, public spaces are being bought up and closed down.

The economist Diane Coyle, writing during the Occupy encampment outside St Paul’s, observed how public life is being designed out of our cities:

One of the striking aspects of the Occupy movement is its claiming of some open spaces in major cities, striking because it puts a line in the ground (literally) against the steady erosion of urban public space during the past quarter century. […]

The enclosure of open space in private malls, the design of street furniture to make sitting down (never mind sleeping) a challenge, the bearing down on demonstrations and gatherings and even photography on the grounds of law and order or security, have all contributed to discouraging public gatherings.

It was the Occupy movement that brought into sharp focus the issue of urban land and its ownership. Occupy in London were camped on ground owned partly by St Paul’s Cathedral and partly by the City of London Corporation. The drawn-out, but ultimately successful legal moves to evict the camp symbolized how urban land is increasingly owned or managed by private interests, even when it appears to be public space. This is the new enclosure movement.

The resistance to enclosure in earlier centuries is an old story, narrated by historians; but the same battles are being fought today against the enclosure of common spaces in our city centres. Once it was physical fences and hedges that demarcated the private ownership of the fields of England; now invisible, metaphorical fences mark out the new enclosures. In a broader context, other common resources, such as the production and sale of seeds, have been enclosed by global corporations wielding intellectual property laws as they scour the world, extracting genetic material, and then patenting these finds as their discoveries. In this way, Third World farmers have lost the rights to use the seeds they have harvested and shared for generations.

But what about the question raised in my post about access to the Mersey shore? Should we have right of access to every inch of our country’s coastline and its beaches? For many, this is a dream to aspire to, alongside the right to roam through fields and across mountain and moorland. At present, it is only a dream, glimpsed fitfully in new legislation.

The Danes and the Swedes have complete right of access to beaches, the foreshore, dunes, cliffs and other uncultivated land. In France, Portugal and the Netherlands the foreshores and beaches are in public ownership. Polls suggest that most English people think they have similar rights. But they don’t. There is a legal right of access only to about half of the English coast. And there is virtually none to beaches. At present, we are only allowed to visit the seaside by a system of often confusing ad-hoc arrangements: when we venture onto a beach we are technically trespassing.

The Ramblers’ Association has long campaigned for a right to roam the entire coastline and beaches of the British Isles. Now the Marine Act 2010 has begun a process – which will take ten years to complete – that aims to achieve exactly that. The intention is to establish a ‘coastal margin’ or ‘strip’ which will be a clear access route, with clifftop walks complemented by ‘spreading room’ such as beaches, dunes, headlands and viewpoints, to allow people not just to walk along a linear path but to take diversions to viewpoints or have a picnic. The Act requires Natural England to publish a coastal access scheme, based on stage-by-stage negotiations with landowners. They’ve got a big job on.

The Crown Estate controls about 45 per cent of England’s foreshore; the remaining beaches are in a variety of hands, from the National Trust and Ministry of Defence, to local authorities and private individuals. When it comes to those private individuals the response to the idea of access is often, in the words of one who commented on my earlier blog, that ‘those who have been successful enough to be able to afford a little privacy’ ought to be left to enjoy their just desserts. Kate Bush, for example, spent £2.5m on 17 acres of Devon coastline, complete with a 1920s cliff-top villa, and private beach.

Another high-profile example (though in a different jurisdiction) involved Jeremy Clarkson who bought a lighthouse on the Isle of Man and then blocked a traditional right of way with barbed wire, arguing that having a public path so close to his property breached his human rights. He lost a legal battle when the court ruled in favour of the rights and freedoms of the general public to walk in the area. The ruling said that although everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, the footpath should remain.

In an example of a successful individual taking a different stance, the novelist John Le Carre gave a stretch of coastline beneath his house near Land’s End in Cornwall to the National Trust in 2000 to protect it against future development and safeguard the rights of walkers using the Southwest coastal path.

When all the negotiating is done and Natural England produces its plan there will be no right of appeal, nor any compensation to the owners of private beaches, hotels, nature reserves, wildfowling clubs or golf courses for any loss of income or capital value. Reporting this, the Telegraph was typically incensed and quoted David Fursdon, the president of the Country Land and Business Association, as saying: ‘This proposal is the sort of conclusion that might have been reached by the Bolshevik politburo, with the same lack of recognition of the legitimate rights of rural business people and property owners. The coast means different things to different people and some have invested heavily in residential environmental and business assets that derive their value from seclusion and tranquillity’.

There’s a long way to go before, like citizens of other European countries including Scotland, we achieve complete freedom to roam where we will over hills and moorland and along the coast of this land we call home; until, as the troubadour sang:

But for the sky

There are no fences facing

See also

- A Short History of Enclosure in Britain: Land magazine

- Still Digging: essay by George Monbiot on Gerrard Winstanley

- The Kinder Trespass: National Trust website

- The financial enclosure of the commons: Antonio Tricarico, Red Pepper, 2012

- We are returning to an undemocratic model of land ownership: Anna Minton, The Guardian

- Paradise Lost? Nerve magazine examines the ownership of Liverpool’s streets

- Coastal Access: information from Natural England on the Coastal Access Scheme approved in 2010

- Coastal Access Natural England’s Approved Scheme (pdf)

- A Brief History of Allotments in the UK

- The Global Land Grab: The New Enclosures: interesting essay detailing the global scale of enclosures

- The Enclosure of the Commons: essay by Vandana Shiva, detailing how biodiversity and knowledge is being ‘enclosed’ through intellectual property rights

It’s a joke really. The last time I wandered out over Salisbury Plain to photograph an Iron Age Fort – (yep, that’s part of our common historical heritage) I was buzzed along footpaths there and back by an enormous dark green, twin rotor army helicopter. When I arrived at the isolated, windswept Iron Age site a private security van appeared from nowhere and two uniformed figures stepped out and scrutinised my every movement. They then sullenly studied me as I left, then when I was out of view I heard the van rev up and angrily roar off in a scatter of flying grit and pebbles. What a lovely day out in the English countryside: yeah, it’s a bit of a joke really :-|

Brilliant stuff, Gerry. Thanks. Here’s one answer: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L7CnrqD1L-Q

Fascinating and thrilling video nivekd, better than anything on TV, best reality show I’ve ever seen. Anyone know the outcome of this? With regard to rights of way, its as if we are being funneled and channeled into certain selected areas where the ‘hoi polloi’ must be herded like sheep. Problem is that the majority of people will not be aware of the underbelly of all this and how much it has slipped into place over the years and creeps through unnoticed and unheralded and the consequences of it are completely lost. As long as the shops are open on Sundays, the milkman calls and the x factor winner has big tits, many people won’t care or give a toss. Maybe I’m too cynical, but the older I get I do see this terrible divide between reality and the dreamworld many people live in, a world full of promises and myths that those in power are happy to see subdue the majority; soma for the masses. I don’t say I am immune, I participate more than some, less than others. But whilst doing my lowly job, I simply see and hear that people do not have a clue how fragile our systems of government; finance; legal; environment and food/water supply chains really are (as a matter of fact I doubt if i truly do) and stuff like this is just so remote from them. But now and whilst there is the internet, knowledge is power and if it can help transform countries and overthrow rogue governments, then we have a chance of slowing down the erosion of liberties here and even reforming some. Years ago none of this awareness would have been possible and the rate of change far too slow to alter anything. I just hope we are raising enough children to have the capacity to think for themselves, question everything and as Joseph Campbell said, ‘Don’t do what Daddy wants’. Follow your own path, whatever the cost.

And then there is the North American First Nations view of land ownership:

“What is this you call property? It cannot be the earth, for the land is our mother, nourishing all her children, beasts, birds, fish and all men. The woods, the streams, everything on it belongs to everybody and is for the use of all. How can one man say it belongs only to him?” (Massasoit), or even more succinctly “One does not sell the land people walk on.” (Crazy Horse). I would maybe think these were romanticized visions from the past if I hadn’t lived in several Oji-Cree communities in Northern Ontario quite recently and, in conversation with elders, come across the same incomprehension of “white people’s” belief that land can be someone’s private property. In Poland on the other hand, when I arrived here 15 years ago there was hardly a fence to be seen in the countryside and it was easy to walk wherever one wished especially as the traditional field boundary is a flat topped bank not a hedge, wall or fence and makes a good footpath. Now along with so many other negative imports from “the west” chain link fences and “no entry” signs are beginning to scar the farmland. We still have the forests and if someone tried to stop Polish people from their annual ritual of roaming in search of mushrooms and blueberries there would surely be an outcry ……. Thank you Gerry for another fantastic and inspiring read – it makes me want to go and rip down a few fences.

This just in; https://www.change.org/en-GB/petitions/iain-duncan-smith-iain-duncan-smith-to-live-on-53-a-week#

This site certainly has all the information and facts I wanted concerning this subject and didn’t know who to ask.

Great post Gerry

Have you come across Clandestine Farm by Anthony Wigens? Small-scale ‘direct action’ to reclaim common rights.

I hadn’t until you drew my attention to it. Unfortunately it appears to be out of print. Amazon are offering a Paladin paperback edition for £24!

“…But on the other side: it didn’t say nothing!”