While I was in Manchester today for a book-signing at Waterstones I made some time to visit The Sensory War 1914-2014, a major exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery marking the centenary of the First World War. Taking as its starting point the gallery’s nationally important collection of art of the First World War, the exhibition explores how artists have portrayed the impact of war on the body, mind, environment and human senses during the century that has elapsed since 1914.

At the beginning of the show are two stark paintings by CRW Nevinson. A Howitzer Gun in Elevation (1917) shows a dull-grey artillery barrel thrusting high into an empty sky, while in Explosion (1916) a fountain of earth is blasted skywards on a distant, muddy ridge. Neither painting features human beings: instead Nevinson focusses on the new technology and its capacity for mass destruction.

CWR Nevinson, Howitzer Gun in Elevation, 1917

CRW Nevinson ‘Explosion’ 1916

But war is a human activity and the exhibition’s aim is to show how artists from 1914 onwards depicted the devastating impact of new military technologies on human flesh and minds. It brings together work from a dazzling array of leading artists including, alongside several more paintings by the excellent Nevinson, others by Henry Lamb,Paul Nash, Otto Dix,David Bomberg, and Laura Knight, plus more recent paintings and photography by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, Sophie Ristelhueber, and Nina Berman. A gruelling experience in parts, I was interested to discover artists whose work had been unknown to me beforehand.

The argument of the curators is that the invention of devastating military technologies that were deployed during the First World War involved a profound re-configuration of sensory experience and perception. Human lives were destroyed and the environment altered beyond recognition. The war’s legacy has continued and evolved through even more radical forms of destruction over the last hundred years. Throughout the century, artists have struggled to understand the effects of modern technological warfare. Military and press photography have brought a new capacity to coldly document the deadliness of modern warfare, while artists found a different way of seeing.

The exhibition is arranged by theme through several rooms. Here is a selection of works that particularly made an impression on me, with additional information drawn from the exhibition’s explanatory panels.

Militarising Bodies, Manufacturing War

The First World War saw an unprecedented mobilisation of combatants around the world. Some 65 million volunteers and conscripts went from all walks of civilian life to become soldiers. The war was truly global and four million colonial troops and military labourers were drafted into the European and American armed forces. It was fought not only in Europe but in the Middle East and in Africa: wherever there were European colonies.

To turn a factory worker, a farm labourer, a clerk or a student into a fighting machine meant militarising them through training. As the title of Eric Kennington’s series of prints puts it, ‘Making Soldiers’.

Eric Kennington, Making Soldiers: Bringing In Prisoners c 1917

Eric Kennington was born in Liverpool. His biographer, Julian Freeman, writes:

A vital, independent talent in early and mid-twentieth-century British art, Kennington became a formidable draughtsman-painter, printmaker, and sculptor (his working practice evolved roughly in that order), and a great portraitist: his figures were often somewhat idealized, but always boldly executed, and frequently in pastel crayon, a self-taught medium in which he came to excel.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Kennington enlisted with the 13th London Regiment. He fought on the Western Front but was badly wounded and and sent home in June 1915. During his convalescence he produced The Kensingtons at Laventie, a portrait of a group of infantrymen. When exhibited in the spring of 1916 its portrayal of exhausted soldiers created a sensation. Campbell Dodgson wrote that Kennington was ‘a born painter of the nameless heroes of the rank and file’.

The series of lithographs, ‘Making Soldiers’ was commissioned by Charles Masterman who was in charge of visual art commissions at the Department of Information. ‘Making Soldiers’ was part of a morale-boosting propaganda project called ‘Britain’s Efforts and Ideals’. The series was exhibited in London in July 1917.

CRW Nevinson, Motor Lorries 1916

The full inventive and productive power of the modern industrialised world was turned to the war effort. New weapons could create mass casualties in a way not seen before. Flame throwers, grenades, barbed wire, mobile machine guns, tanks, Zeppelins, aeroplanes and large-scale artillery, such as the Howitzer, could annihilate the environment and pulverise bodies. The development of this military technology and the mass production of shells and bombs ushered in a new era of modern war, which was an assault on bodies, minds, and landscapes, filtered through the human sensory realm. The noise of war began on the home front, in the deafening and dangerous armaments factories. Significantly, it was artists who communicated the din of the factories, the sonic pounding of high-powered artillery, the storm of marching ground-troops, and the clashing of bayonets and boots. Artists visually linked the ferocious technology of the war to the process of militarisation.

CWR Nevinson employed his Futurist depiction of the human body to great effect to show how the soldier was turned into a cog in the machine of war. He paints the soldiers in Motor Lorries with the same harsh geometry as the cold hard girders they are carrying in. In all Nevinson’s paintings of this period he used a palette of mud browns and the blues of leaden-skies and cold steel to create a harsh and inhuman world.

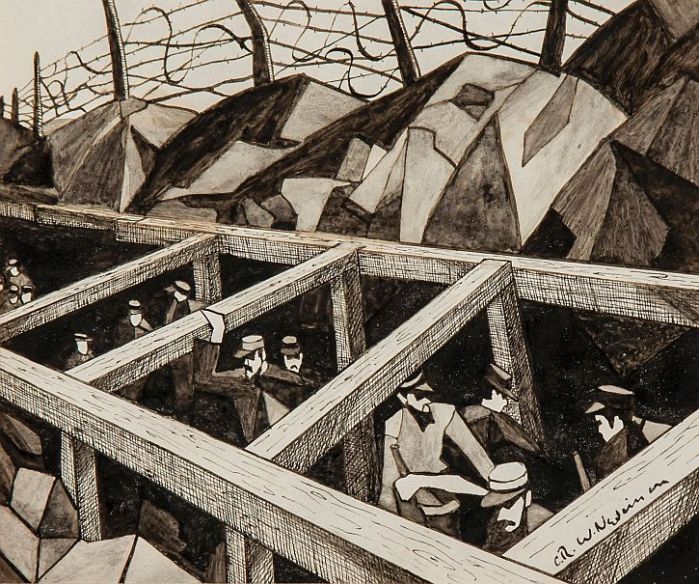

CRW Nevinson, La Guerre des Trous (The Underground War), 1915

The French soldiers in this giant fortified trench wait for the call to go over the top (possibly in Woesten, near Ypres, where Nevinson was stationed). The barbed wire – a major new technology used extensively in the First World War – forms a twisted, menacing skyline. The famed writer, Guillaume Apollinaire recognised that Nevinson had outgrown the bravado of Futurism’s machismo, and was instead ‘making palpable the soldiers’ suffering and communicating to others the feelings of pity and horror’

CRW Nevinson, Returning to the Trenches, engraving, 1916

David Bomberg, Study for ‘Sappers at Work: A Canadian Tunnelling Company’, 1918

David Bomberg was a pioneer of the English movement Vorticism, founded by Wyndham Lewis, which attempted to create a local version of Futurism. Bomberg served with the Royal Engineers and the 18th King’s Royal Rifles before being asked to commemorate the service of Canadian soldiers. This work, done in black and red chalk on paper, is an abstracted study for a more figurative official commission for the Canadian War Memorials Fund, now in the National Gallery of Canada.

Amongst the new sensory experiences created by the First World War was the experience of waging war by working underground. Canadian and Yorkshire miners (sappers) excavated a tunnel at St Eloi to plant a huge mine under Hill 60 at Messines Ridge, near Ypres. The tunnel took eight months to complete. It was detonated in March 1916 obliterating the landscape and leading to devastating loss of life on the German front line – two whole companies of men were killed. The event was portrayed in the Sebastian Faulks novel, Birdsong.

CRW Nevinson, Making Aircraft: Making the Engine 1917

In Nevinson’s Making the Engine, the machines and men have merged in a picture resonating with the hammering din of the wartime factory. The image seems to vibrate simulating the whirring, deafening noise of industrial spaces reverberating with the production of war machines.

George Clausen, Making Guns: The Furnace, 1917

Several works in the exhibition derive from projects to document the wartime effort of workers in the armaments industries, including two by George Clausen. The lithograph Making Guns: The Furnace implies the future violence of a large gun forged in a blaze of fire and molten steel.

George Clausen, Study for ‘The Gun Factory at Woolwich Arsenal’, c.1919

Clausen’s, Study for ‘The Gun Factory at Woolwich Arsenal’ in pencil, watercolour and pen and brown ink was made in preparation for a large painting commission to document 74,000 munitions workers occupied at this vast factory site. Shades of light permeate the study streaming in and around the centrepiece of the colossal machinery used to mould gun-barrels. The press resembles a gigantic beast against the barely visible workers below.

Female Factories

The mass mobilisation of society meant that women’s bodies were just as critical as men’s in the conduct of Total War. In Britain alone, over seven million women were mobilised into wartime industries and public services, with over one million working in the munitions industry. Around 60,000 served in the armed services, and thousands volunteered for the medical corps. Though munitions work was dangerous and exhausting, and resisted by Trade Unions as ‘only for the duration’, it offered women paid employment, a degree of independence and a feeling of direct involvement in the war effort. The Society for Women Welders, for instance, was formed in 1915 and by 1918 had 630 members.

Laura Knight, Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring, 1942

In the Second World war, female munitions workers became symbols of modernity by challenging perceptions of women’s capabilities. Wearing men’s dungarees, engaged in both skilled and physical labour, they adapted their bodies and minds to the taxing work of heavy engineering or the risk of making explosives. Artists reflected this temporary change in women’s roles depicting the militarisation and modernity of the female body.

Laura Knight’s heroic depiction of a woman factory worker in the Second World War has become an iconic image. The eponymous Ruby was a skilled machinist in the Royal Ordinance Factory in Newport, Monmouthshire. The breech ring she is lathing was for a Bofors breech gun; a notoriously difficult engineering task to complete to the required precision without making the gun a suicidal hazard to use. The painting was widely discussed on the radio and produced in poster form as a propaganda tool for distribution to other factories. In America the more fictional Rosie the Riveter became equally famous through the distribution of posters.

CRW Nevinson, Making Aircraft: Acetylene Welding, 1917

The two women featured in this lithograph wear protective eye-goggles, aprons and scarves. Nevinson’s skilled use of the graphic technique conveys the sensory elements of flying sparks that almost singe the exposed arms, hands and clothes of the women, and draw in the viewer. Absorbed in their skilled task, the women become anonymous bodies in the war machine, a familiar device in art of the period only usually applied to soldiers’ bodies.

Archibald Standish Hartrick, Women’s Work: On Munitions, Dangerous Work (Packing TNT), 1917

Hartick completed lithographs for the series, ‘Britain’s Efforts and Ideals’ on the theme of women on the Home Front. For the first time women were recruited to the war effort, working in the munitions factories making the very instruments of death which wrought terror in the trenches. The work of the munitionettes or Canary Girls as they were called due to the yellow discolouration of their skin from TNT, was indeed highly dangerous. Many were killed in munitions factory explosions such as the one at the National Shell Filling Factory at Chilwell, Nottingham in 1918 which killed 137.

Archibald Standish Hartrick , Women’s Work: On the Railways, Engine and Carriage Cleaners, 1917

Archibald Standish Hartrick , Women’s Work: On Munitions – Heavy Work (Drilling and Casting), 1917

Pain and Succour

In the First World War over two million soldiers from Britain and the colonies of its Empire were wounded. The medical corps was charged with evacuating the wounded from the battlefield, treating them in field hospitals and at home, so that they could eventually be returned once again to the front-line: an absurdity not lost on those hoping for a ‘blighty wound’ (a light wound but needing treatment at home).

Artists depicted the chaotic flow of patients in the front-line casualty station, the wounded soldier’s experience of pain and helplessness the moments of tenderness as doctors and nurses attempted to alleviate the agony of their wounds, or the shock of witnessing the death of comrades. Succour was often felt as a temporary bond between patient, stretcher-bearer and nurse. Women’s role in front-line surgery and hospital medical care was both professional, publicly contentious and, at times, also intimate. Doctors also shared the personal cost of the war, with thousands killed and wounded.

Artists understood the inhumanity of modern war as a collective experience of horror and indiscriminate maiming that reached across the classes and genders. They depicted the ashen-faced stretcher-bearers carrying their burden under a gangrenous sky, the lone nurse in the darkened space of the casualty theatre, and the arduous journey of evacuation from the frontline to the hospital back home.

Henry Tonks, An Advanced Dressing Station in France, 1918

Here, Henry Tonks dramatises his intimate knowledge of shrapnel wounds to the head and body, and the procedures of frontline evacuation medicine under the chaos of military attack. The sensory qualities of this painting are revealed in the lurid glow of burning buildings and the choking haze of smoke-filled air; in patients’ grimaces; in their endurance of gripping pains, and in the relief that a drink of water brought to the desperately wounded.

Like Henry Lamb, Tonks was a doctor-turned artist. Before the war he was the Director of Drawing at the Slade School of Art where he taught Paul Nash, Stanley Spencer and CRW Nevinson, amongst others. He served as a surgeon in the Royal Army Medical Corps.

Henry Lamb, Advanced Dressing Station on the Struma in 1916, 1921

This painting is a scene of medical aid being given to the wounded man on a stretcher, but is also symbolic of the pain and succour of the entire war with its almost religious composition. Lamb was commissioned in the Royal Army Medical Corps and sent first to Salonika (Thessaloniki) in Greece with the British Salonika Army in 1916 in late 1917 to Palestine. On his return Lamb, who had won a Military Cross for gallantry, began to turn his experiences into his most important works. A small number of drawings and watercolours were exhibited at Manchester City Art Gallery in 1920. One of these, Succouring the Wounded in a Wood on the Doiran Front prompted the Gallery Director, Lawrence Haward, to commission Lamb to turn it into a major painting as the beginning of a war art collection for Manchester.

The River Struma was the site of a little-known campaign to repulse the Bulgarian invasion of eastern Greece and to achieve the ultimate liberation of Serbia from Bulgaria and the Central Powers.

Paul Nash, Wounded, Passchendaele, 1918

The majority of Nash’s works from the front depict soldiers at a distance engulfed by the blasted landscape. Here Nash’s pathos at the plight of the soldier is more direct as the stretcher-bearers carry the wounded through a poisoned landscape filled with the colours of gangrene and mustard gas.

Harold Sandys Williamson, A German Attack on a Wet Morning, April 1918

Harold Williamson joined the King’s Rifles as a rifleman and was promoted to Lance Corporal in the 8th Battalion. In this painting the artist depicts his own wounding by a grenade during a battle near Villers-Bretonneaux. He hobbles away from the scene, gripping his bleeding hand. A comrade Iies dead in the foreground while the misty haze over the morning assault captures the confusion of battle. Williamson wrote:

In the gloom and rain the storm troops then came over and smashed through our two first lines…Two men are firing a Lewis gun. The wounded man has a poor chance of getting away; he must cross much open country swept by enemy fire, and go through a heavy barrage.

Williamson’s wound was serious enough for him to be repatriated to England. Experiencing and witnessing the extent of suffering in modern war underpinned the intense sensory feel of the work of war artists like

Williamson.

Claude A Shepperson, Tending the Wounded: Advanced Dressing station, France, 1917

Claude A Shepperson, Detraining in England, 1917

Claude Shepperson was an illustrator for various magazines. He created this sensitive series of lithographs depicting the passage of the wounded from the front line to recovery in England as part of the ‘Britain’s Efforts and Ideals’ series of propaganda prints.

Embodied Ruins: Natural and Material Environments

The extensive destruction of rural France and Flanders in the First World War was felt as an atrocity, deeply scarring the collective psyche. The ruined Iandscape came to stand for the dead themselves. Artists like Paul Nash and William Orpen expressed their feelings for the loss of men through depicting the aftermath of the battlefields in images of putrid mud, charred and torn trees, and waterlogged shell-holes. The churned earth appeared as gangrenous wounds, ruined buildings like injured faces, and destroyed military hardware as ruptured corpses. At times, these desolate environments have a terrible beauty. Nature was violated but it was also resilient.

In contemporary works this use of landscape as metaphor is seen in Sophie Ristelhueber’s photographs of the disfigured territory of the West Bank and in Simon Norfolk’s carcass-like military hardware strewn across the deserts of Afghanistan.

Paul Nash, The Field of Passchendaele, 1917

Nash enlisted in 1914, but only arrived at the front in February 1917. In May he fell into a trench and was injured badly enough to be sent home again. When he returned in late October he witnessed the final stages of the battle of Passchendaele, which was fought over the summer months into November. His regiment, the Hampshires, had been almost completely wiped out in the battle for Hill 60 in August. The drawings he made, such as this one, were all begun on site. The landscape of battle debris, churned mud and rancid water-filled craters in the undraining Flanders clay after the heavy summer rains touched Nash deeply. He was able to make these landscapes of the aftermath of war into metaphors for the human body destroyed by conflict.

William Orpen, The Great Mine, La Boiselle, 1917

William Orpen first visited the Somme in April 1917 as an Official War Artist under the auspices of the Department of Information after the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line. His principal task was to draw and paint the officers but he had time to wander the battlefields. Returning to the Somme again after the summer he was amazed to find, ‘The dreary, dismal mud was baked white and pure – dazzling white. White daisies, red poppies and a blue flower, great masses of them, stretched for miles and miles’. La Boiselle is the site of one of the giant craters created by huge mines laid under the German trenches.

William Orpen, Village: Evening, 1917

Artists were not only struck by these vast wastelands, they also felt the terrifying impact of war on the domestic front. They depicted the ruin of the material and built environment in Flanders – roads, villages and churches where shattered homes and putrefying corpses are equated with ruined bodies.

Sophie Ristelhueber, WB #8, 2005

The apocalyptic imagination is refracted through Sophie Ristelhueber’s approach to the landscapes of recent conflicts in former Yugoslavia, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and the West Bank. The WB series depicts roadblocks with deeply ambivalent sensations. In WB #8, the viewer stands before the gritty impasse; slowly the eye travels beyond, only to be confronted with an impenetrable set of barriers, and further still, a settlement on the horizon appears impossibly faraway. The artificial topography of man-made violence in zones of conflict and disputed territory is strangely sensual and fleshy. The barricades appear as brutal, jagged scars on an ancient geological body.

Shocking the Senses

Modern war produced terrifying sights, putrid smells, and nerve-shattering sounds that shocked the human senses. In the confined spaces of tanks trenches and submarines, bodies felt compressed and minds became stressed. ‘Thousand-yard stares’ panicked expressions, nervous ticks, and hysterical gaits were physical responses to emotional and sensory trauma.

In 1915 British neurologist C.S. Myers invented the term ‘shell shock’. The term aptly conveyed the sensory assault of artillery bombardments and the repercussions on the individual of industrialised modern warfare. Military medicine lost control of the term as it entered the public vernacular and its psychological and emotional complexities were distilled into the myth that shellfire was the sole cause of shell shock. Unlike the stigma attached to psychiatric disorder, shell shock enabled families to preserve the dignity and heroic sacrifice of loved ones.

Artists and writers, many of whom were afflicted with shell shock, were crucial figures in translating its symptoms to audiences and rendering visible this disturbing yet invisible wound. Siegfried Sassoon described the unceasing ‘thud’ of bombardments: ‘I want to go out and screech at them to stop…I’m going stark, staring mad because of the guns.’

Repatriated home, CRW Nevinson recalled his ‘delayed shock’ as ‘uncontrollable tremblings’ and vomiting, a sense of foreboding and rage. Terrified faces and distressed bodies became the subject of artistic empathy during the First World War.

Over the century, artists have been combatants, captive prisoners and anti-war activists, engaging with other people’s suffering and visualising the repetitive nightmare of trauma. Some have confronted torture, executions, and genocide as the abyss reached when human lives are seen as barely human. Artists have also been compelled to show that trauma is not the preserve of soldiers. The shocking sights of agonised women and children, of rape, disease and starvation, and the powerlessness of grief, have entered the darkest artistic imaginings.

Otto Dix, Der Krieg 28: Seen on the Escarpment at Clery-sur- Somme, 1924

The hellish,visceral and hallucinatory quality of Der Krieg is undeniable and the artist created perhaps the most powerful, and sensory, anti-war works of art of the twentieth century. Dix consciously took inspiration from Francesco Goya’s series of prints, The Disasters of War which recorded the horrors of the Napoleonic invasion of Spain and the Spanish War of independence from 1808-1814.

Pietro Morando, One of the brave struck down, San Marco, 1917

In Britain, we know little about the Italian Front in the First World War, fought in the mountainous borderlands between Austro-Hungary and Italy. In freezing conditions, this front was soon bogged down in trench stalemate. In 1916-17 Pietro Morando fought as a volunteer in the Arditi (Italian elite troops) on the front-line in the limestone Karst country bordering Italy and Slovenia. He made drawings on any pieces of paper he could find. His works have an immediacy of perception and a sense of the artist’s urgent need to note down the painful and deadly events at the front and in the prison camps of Austro-Hungary.

Pietro Morando, At the prison camp of Komarom, Hungary, 1918

Morando was captured during the retreat from the Piave River in 1918. His charcoal sketches (from an album dated 1915-1918) describe the torture, executions, cholera and starvation he witnessed while imprisoned in the Hungarian camp of Nagymegyer and in the city of Komarom. In addition to the privations of military prisoners, during the conflict thousands of Italian civilians were interned and died of malnutrition.

Richard Serra, Abu Ghraib, 2004

Serra transformed the horrific, mass-circulated image of torture into a lithograph of the faceless, nameless Iraqi prisoner in Abu Ghraib. Another, larger, version of this print is more directly a protest work and bears the words ‘Stop Bush’.

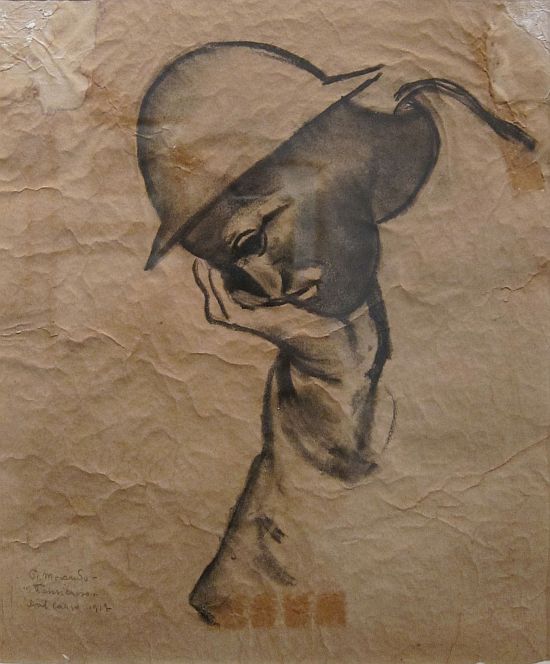

Eric Kennington, Bewitched, Bemused and Bewildered 1917

This depiction of an exhausted, sleep-deprived and disoriented soldier was also titled Via Crucis (The Way of the Cross). The censors tried to prevent it from being exhibited in Kennington’s exhibition of war art at the Leicester Galleries in July 1918. The title Bewitched, Bemused and Bewildered comes from lines to a popular song of the day. Kennington wrote: ‘Must the soldiers endure the most hideous agony and the civilian not be permitted to think of it second-hand?’

Pietro Morando, Thoughtful, On the Carso, 1917

Otto Dix, Der Krieg 35: The Madwoman of St.-Marie-a-Py, 1924

The shocking impact of bombardments on civilians is powerfully conveyed in The Mad Woman of St-Marie-a-Py. Her baby lies dead among her ruined home while she beats her bare breast in the agony and powerlessness of grief. This is a rare but stark moment of Dix’s sorrow for the innocent casualties of men’s wars as we are forced to share in her state of absolute distress.

Conrad Felixmoller, Soldier in the Madhouse, 1918

Gripping the asylum cell window, and perhaps even chained to the bed, Conrad Felixmoller’s Soldier in the Madhouse has jagged furrows in his forehead; the work portrays the desperate isolation of the shell-shocked patient.

Rupture and Rehabilitation: Disability and the Wounds of War

Away from the battlefield artists depicted the impact of wounding on the body. Modern medicine saved soldiers lives, though they often survived with terrible, disfiguring wounds. The artists who served as medical illustrators in the First World War were closely involved with the new field of plastic surgery as it attempted facial and bodily reconstructions. In delicate pastels and watercolours intended as medical studies they also saw the fragile humanity of those with such horrific wounds. They found amputees and blinded men recovering in hospital, undergoing physical and vocational rehabilitation. In many of these works we see a compassionate rapport between the wounded sitter and the artist, sensitive to the intimate depths of suffering as pained eyes meet our gaze. The courage, pride and silent dignity of the wounded are deeply moving.

In the 1920s wounded soldiers were fitted with artificial prosthetic limbs. Artists were sceptical of this revolution in prosthetics which held out a fantasy of the cyborg – half man and half machine. It promised that the body destroyed by modern technology could be reconstructed into a hyper-masculine, superhuman being. However artists like the German Heinrich Hoerle saw the reality of living with disability and approached the notion of the superhuman man-machine with bitter irony. More recently, as women have entered the war zone as combatants, artists have highlighted both the frailty and resilience of disabled veterans of both genders.

Henry Tonks, Saline Infusion: An incident in the British Red Cross hospital, Arc-en-Barrois, 1915

Tonks’ medical training, his understanding of wounds and their treatment and his sensitive use of pastel come together ‘in this study made in northern France. Tonks turns the secular scene into a work with religious overtones, arranging the composition as a Descent from the Cross. Tonks is most well known for his medical studies of facial wounds in pastel – a subject which has featured in the novels of Pat Barker such as Toby’s Room.

Heinrich Hoerle, Help the Cripple, 1920

The Cripple Portfolio was published in 1920 by Cologne Dada artist, Heinrich Hoerle, in the context of the 2.7 million disabled German veterans who had returned home from the Front. 67,000 of these veterans were also amputees. The Weimar Republic instituted a system of rehabilitation and employment, which caused resentment amongst the able-bodied as the Great Depression of the 1930s took hold. Some 90 per cent of disabled soldiers were employed. The subject of Hoerle’s portfolio of prints is the intimate suffering of the lives of the disabled in the aftermath of war. It is divided into six scenes of the everyday life of the wounded veteran and six of his dreams and nightmares.

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, Michael Jernigan, Marine Corporal, 2006

Michael Jernigan lost his sight in an attack with an IED (Improvised Explosive Device) while serving in Iraq. Like so many marriages, Jernigan’s failed when he returned home so badly injured. In Greenfield-Sanders’ photograph, attention is drawn directly to the diamonds from his wife’s wedding ring which Jernigan had set into one of his eight prosthetic eyes.

Nina Berman, Marine wedding, 2006

Nina Berman is a documentary photographer, author and educator. Much of her photographic work focuses upon the American political and social landscape, including the militarization of American life and the dialogue around war, patriotism and sacrifice.

Her 2006 photo Marine Wedding, probably one of her most recognizable works, is a haunting picture. The bride, in a red-trimmed wedding gown with beading on the bodice and skirt, holds a crimson bouquet, and the groom wears his navy-colored military dress uniform. But neither smiles – they look past the camera in opposite directions. And the groom, an Iraq War veteran, has no ears, nose, or chin. His face looks like it is covered with a plastic mask. Severely burned in 2004 after a suicide bomber attacked his truck, his skin melted when he was trapped inside. Marine Wedding won a 2006 World Press Award.

Rosine Cahen, Hospital Villemin (2 January 1918), 1918

I had never encountered the work of Rosine Cahen before, but I found her delicate portrayals, in charcoal, pastel and white chalk, of wounded and disabled soldiers among the most memorable of the exhibition.

Born in Alsace and trained at the Academy Julian in Paris, Rosine Cahen (who was mostly known as a print-maker) turned to delicate pastel, chalk and charcoal to draw the wounded and disabled soldiers she visited in French hospitals during the war. In her sketches, the observer is so discrete we are never allowed to gawk at the men’s wounds, but rather it is their faces in a state of almost serene despair that she portrays. These works exude great calmness both in the men’s expression and in the way the artist alludes to the intimate relationship of these captured moments.

Cahen gives these wounded men their dignity – they are never just medical objects. She was 59 years old in 191 6 when she began visiting the war hospitals of Paris and Monte Carlo. She continued her visits on numerous occasions over the following three years. The age difference enabled her to build a personal rapport with the soldiers while they ‘sat’ for her, quietly recovering.

In Hospital Villemin, 2 January 1918, the facially wounded patient is disguised under bandages, contrasting with his luminous purple shirt. A solitary eye peers out, as he tries to eat some thing from his tray.

Rosine Cahen, Hospital Rollin (October 1918), 1918

This is a portrait of an amputee from the 17th InfantryRegiment, wounded on 21 August 1918, near Soissons in Picardy. Preoccupied with reading his gazette, a little blue slipper juts out of his trouser leg. The space next to it is empty and crutches reveal his early stage of recovery.

Rosine Cahen, Hospital Villemin (8 April 1919), 1919

A blind soldier practices Braille while sitting in bed recovering from his injuries. Wounded soldiers were

expected to begin the rehabilitation before they were fully recovered. In the background are little sketches of the same patient, perhaps completed on other occasions.

Rosine Cahen, The Amputees’ Workshop, 1918

This study reveals the temporary wooden leg of an amputee which juts out awkwardly, uncomfortably, under the table. His left hand is also amputated. Cahen captures him absorbed in his writing task.

See also

- Otto Dix’s War: unflinching and disturbing, but dedicated to truth

- Kathe Kollwitz’s ‘Grieving Parents’ at Vladslo: ‘Seed Corn Must Not Be Ground’

- The Art of War

- A Terrible Beauty: British artists in the First World War

- Stanley Spencer’s Sandham murals: ‘a heaven in a hell of war’

- Paul Nash and World War One: ‘I am no longer an artist, I am a messenger to those who want the war to go on for ever… and may it burn their lousy souls’

- The Great War in Portraits: patriotism is not enough

- History and war in the 20th century: a storm blowing from Paradise

- Leeds art: pain, war, atonement and dance