‘You never see the sun in my work … because I can’t paint shadows. I kept trying for years’.

So said LS Lowry. But, in Salford on Tuesday to see A Lowry Summer, the exhibition mounted by The Lowry to mark the artist’s 125th birthday year, I thought maybe the real reason was that the sun never bloody shines in this city. I know that’s a base calumny on Manchester, but the rain was coming down like stair rods (northern colloquial, archaic: look up on Google), and had been for nearly 48 hours without pause. This wasn’t a Lowry summer: it was a deluge.

Actually, with almost the whole of the Lowry Collection on display, alongside paintings on loan which have never previously been displayed at The Lowry, this exhibition is something of a Lowry deluge. It is a truly comprehensive survey of the artist’s output – warts and all.

In the early seventies, when my generation were establishing ourselves after university, a common sight inthose first flats was an Athena poster of a typical Lowry northern industrial landscape. Popular recognition had come late for Lowry (he was in his 80s by then), but for a while his star was definitely in the ascendant (in 1967, Status Quo’s first hit single had popularized his ‘Pictures of Matchstick Men’ and in 1976 he received an honorary DLitt from my old uni, Liverpool).

Of course, we now know – largely thanks to the exhibitions mounted by The Lowry since its inception in 2000 – that Lowry painted a lot more besides industrial landscapes populated by tiny stick people. He painted continuously throughout his adult life, keeping the activity secret for over forty years while working as a rent collector in Salford. This exhibition showcases all aspects of his work – the industrial townscapes alongside early drawings, portraits, through to later rural landscapes and seascapes.

More than anything, though, the exhibition causes the viewer to question some common assumptions about Lowry – the man and the artist. To what extent do those scenes of working class northerners at work and play represent a benign view of the people portrayed? How significant an artist is Lowry – and which of his works represent his greatest achievements? Walking around this extensive – and exemplary – exhibition, the inescapable conclusion was that the works on show ranged from the great to the truly awful. Indeed, one wonders whether Lowry would ever have wanted some of his late caricatures to be put on public display.

I am tired of people saying I am self-taught. I am sick of it. I did the life drawing for twelve solid years, and that I think is the foundation of painting

– LS Lowry, 1968

The show features many early pencil drawings and portraits which reveal his artistic skill. Among some excellent early portraits in pencil and oil on show here are ‘Portrait of a man looking right’ (1914), ‘Male Model’ (1908), ‘Model with headdress’ (1918), ‘Boy’ (completed in 1913 and depicting a family friend killed in First World War), ‘Artist’s Mother’ (c1920) and ‘Seated Male Nude’ (1914).

These are fine works, rightly valued by Lowry just as much as his more well-known paintings. They show that Lowry was adept at handling line and tone. Lowry was always irritated by people who thought he was an amateur painter, self-taught and untutored: ‘Started when I was fifteen. Don’t know why. Aunt said I was no good for anything else, so they might as well send me to Art School…’. In a profile of his career on The Lowry website, his early training and influences are summarized:

In 1905 he began evening classes in antique and freehand drawing. He was to study both in the Manchester Academy of Fine Art and at Salford Royal Technical College in Peel Park. Academic records show him still attending classes in the 1920s. Lowry knew from his teachers – people like the Frenchman Adolphe Valette – how French Impressionism had changed the painting of landscapes and the modern city. He knew from exhibitions in Manchester what the current trends in modern art were, and deeply admired Pre-Raphaelites like Ford Madox Brown and Rossetti. Far from being a naïve Sunday painter, Lowry was an artist looking for his own distinctive way of painting and drawing – and for a subject matter he could make his own, preferring eventually the view from the Technical College window to that of the posed model.

A View from the Window of the Royal Technical College, Salford (above), a pencil drawing made in 1924, shows the view from the art school balcony (now Salford University Peel Building) and has been described as ‘the pinnacle of the artist’s achievement with the pencil …The composition is stunningly daring and the whole work a synthesis of every shade of technical mastery from tightly controlled to brilliantly free loose drawing’.

Lowry continued to draw compulsively until the last years of his life, producing a huge range of works including highly finished drawings of a life model, careful portrait studies, rapid sketches made on location and charming sketches of children and dogs. Lowry did not merely see drawing as a means to an end in producing his paintings, but as a significant and worthwhile medium in its own right.

But, as this exhibition reveals, these pencil portraits in later years turned into caricatures and grotesques. By the 1960s he was producing caricatures in drawings and paint of people with enlarged moon faces, such as ‘Man in a Trilby’, 1960.

There are many of these on display, most of them execrable (‘Man in a Trilby’ is actually one of the more acceptable ones). One critic of these late drawings complained that Lowry was producing ‘ . . . derogatory caricatures . . . which may well be intended to disclose a tenderly humorous attitude to his fellow creatures [but] seem to me to be distressing documents of a breakdown in communication, not really intended for exhibition.’

In 2000, on the ocassion of The Lowry’s opening, Jonathan Jones, wrote a searing critique of the late portraits – and Lowry’s work in general – in The Guardian:

Lowry’s late portraits are very bad. They lack any sense of idiosyncrasy or attention to the person painted; they have big, mad, staring eyes, are grotesque, sentimental

As Lowry became older his fascination with the people he saw on the streets, or from a bus, focussed increasingly on the oddest or most bizarre characters.

There’s a grotesque streak in me and I can’t help it . . . They are very real people, sad people . . . I’m attracted to sadness, and there are some very sad things.

Lowry was by this time a well known and successful artist and many people, including collectors and dealers, found these works too challenging a departure from the industrial scenes they were familiar with. In drawings made towards the end of his life – and probably never intended for exhibition – figures transform into surreal animals or ghost-like shapes. ‘Isn’t it awful that l have to create them?’ he asked, ‘Why do l do it?’ I feel more strongly about these people than I ever did about the industrial scene … There but for the grace of God go I.’

It’s an attitude seen in his earlier ‘The Cripples’, painted in 1949.

Lowry said of this painting, ‘The thing about painting is that there should be no sentiment. No sentiment’. But his friend Hugh Maitland surprised him by declaring that there was no compassion in these late paintings.

Perhaps Lowry’s best-known work outside of the urban landscapes is ‘Head of a Man’, completed in 1938. It’s an arresting work, described by one critic as ‘like a reflection one might catch of oneself after a sleepless night, all healthy vigour drained, leaving only strain, tension, physical discomfort and utter despair’, and it is indeed a portrait of inner disturbance and unhappiness.

I started a big self-portrait and then I thought, ‘What’s the use of it. I don’t want it and nobody will’. I turned it into a grotesque head, I’m glad I did, I like it better than a self-portrait.

The painting was one of several completed in the 1930s which reflect a period of trauma and unhappiness in Lowry’s life. Lowry was an only child and lived with his mother and father. His mother always insisted that she had wanted daughters and that her son disappointed her. As for his father, their relationship had always been cold and strained. In 1932, his father died of pneumonia and his elderly mother took to her bed, making constant demands on Lowry who cared for her withjout any additional help until she died in 1938.

Not only was Lowry required to be at his mother’s beck and call, he also discovered that his father had run up sizeable debts which it took Lowry a year to settle. With the strain of work and looking after his mother, Lowry’s health deteriorated. He later said of the period:

I think I reflected myself in those pictures. That was the most difficult period of my life. It was alright when he [his father] was alive, but after that it was very difficult because she was very exacting. I was tied to my mother. She was bedfast. In 1932 to 1939 I was just letting off steam.

Completed in 1950, ‘A Father and Two Sons’ (seen at the top of this post) has something of the same psychological aura.

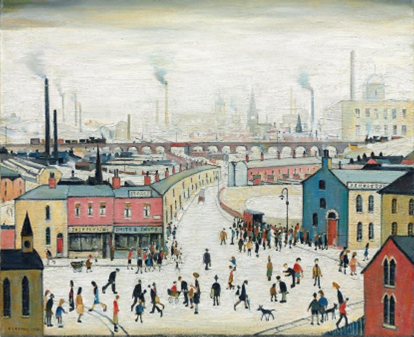

‘Britain at Play’, painted in 1943, is a painting I hadn’t seen before (it’s on loan from the Usher Gallery in Lincoln). It’s a vibrant canvas, a classic example of Lowry depicting city crowds on holiday. It teems with tiny figures, is part imaginary, part based on real locations. Like his other urban landscapes, it is, I think, a celebration of the northern industrial working class experience. However, others see differently. For example, Howard Jacobson has stated that when we see these paintings this way we are guilty of a major misunderstanding. ‘We have taken Lowry’s matchstick men and matchstick cats and dogs’, he says, ‘to be warmly appreciative, nostalgic evocations of the teeming street life of Manchester and Salford’. This is wrong. In the 2007 Lowry Lecture he stated:

Dwarfed by the mills, the chimneys and the chapels, they are foreground without function, the very peremptoriness with which they’re drawn – for why would one reduce the various and abundant fleshiness of humanity to a matchstick silhouette? – the proof that their individuality is not what matters to Lowry. They are a crowd, a cluster, a congregation, viewed by someone who is not of them – not contemptuously or satirically, but from somewhere they are not – figures of loneliness themselves, congregating and yet separate, a mystery to the painter. And that’s the subject – not their street-corner, ragamuffin heritage vitality, and not their servitude to capitalism – but their mystery.

Lowry’s work is, according to Jacobson, a brutal consideration of the modern world and the lack of communication between people, he argues, and is reminiscent of the work of the playwrights Harold Pinter and Samuel Beckett.

There is a painting held here in the Lowry Centre entitled ‘The Lake’. Had Lowry called it The Waste Land or Golgotha or A Vision of Hell, he might have found appreciation for it, and for works on a comparable scale, much sooner. […]

Visionary is the only word for a painting like ‘The Lake’. Apocalyptic, even. Indeed I am not sure that a more visionary or apocalyptic painting has been painted by an English painter in the last 100 years. In the background the city belches its smoke – the whole city, not a glimpse of Agecroft or Pendlebury, but Manchester viewed panoramically as a Canaletto might have designed it – its public buildings, the town hall, the cathedral, of equal standing with the factories, and at first sight belching smoke themselves – but seen allegorically, too, as Blake might have conceived it, Manchester the black and golden city, almost a parody of Jerusalem, coughing out its chaotic promises into a sky that is neither day’s nor night’s. In the centre of the painting a rotting lake – not a lake made by nature, but seemingly a lake of effluence and seepage into which the land is steadily sinking and which appears to be encroaching upon the black and golden city itself. Boats are half submerged in this lake, posts and dead trees and other debris protrude from it. In the foreground, telegraph posts and palings echo the chimneys further back, but they also resemble crosses – hence my alternative title, Golgotha. And among the crosses are what appear to be tumbled down gravestones – the dead granted no more beauty or dignity than the living. The dead disregarded, disrespected, on the very edge of this toxic lake – poisoning it and poisoned by it.

Had ‘The Lake’ been painted in east Germany by an expressionist we would have known where we stood with it. “Sterility, anguish, impotence, redemption promised in the deceiving luminosity of the polluted sky, the unnavigable waters of ruination, the Styxian lake of abandonment and despair…” I have the essay half finished as we speak.

But that’s not how we talk about Lowry. It probably isn’t how we should talk about anybody, but you take my point … In fact, the usual reading of Lowry’s more familiar industrial landscapes has hindered our understanding not only of the more desolate, evacuated paintings, but of the better-known Lowrys too. They are all essentially, in my view, paintings without people in them, even when there are people in them; all – whether they contain gravestones or symbolic crucifixes or not – landscapes of isolation.

‘Coming from the Mill’ (1930) is typical of Lowry’s urban landscapes, a vivid record of life in industrial northern England. Lowry thought it his most characteristic Northern industrial landscape. Based on a pastel drawing made in 1917, it is one of his first ‘composite’ industrial scenes. By this point, his use of spindly figures, had become the characteristic feature of his work. In the early paintings, each ‘matchstick’ figure was carefully and individually depicted. But as the years went by the figures in the big townscapes became less distinctive, more anonymous members of the crowd. That fact, perhaps contributes to the interpretation of these canvases conveying a sense of bleakness, rather than affection. As noted in this exhibition, Lowry used a limited palette of drab colours to portray urban buildings, overcast skies, and smoking factory chimneys – further reinforcing the atmosphere of desolation.

In his critique of Lowry’s work in 2000, Jonathan Jones wrote:

The Lowry paintings worth looking at are the ones everyone knows. There’s no point trying to turn him into a well-rounded artist because he wasn’t one. He was a melancholy compulsive who painted the industrial north of England through deeply disturbed eyes, and caught aspects of it no one else was prepared to look at. It is easy today to sneer at matchstick men but no one can ignore the real authority of a painting like ‘Coming From the Mill’ (1930). It’s a terrifying vision. The lowering buildings are so much more real than the people. Windows repeat themselves in a thudding, monotonous rhythm that is continued by the people trudging along. This is not an angry painting; it is numb. Lowry has internalised what he feels is the city’s spiritual death.

Lowry painted the social world of Salford and Pendlebury systematically, illustrating how the factories produced people deprived of identity. His most disturbing images of the working-class crowd depict moments of supposed freedom and leisure: a drawing from 1925 of the bandstand in Peel Park shows people gathering like maggots around a piece of food, while above them the chimneys tower. Again and again he paints the crowd’s attempts at leisure as feeble reproductions of the discipline of the factory. ‘Going to the Match’ (1953) makes supporting the local football team seem a desperate ritual. One of his scathing images of a crowd trying to forget the factory is called ‘Britain at Play’ (1943).

‘Going To The Match’ won a Football Association competition in 1953. Depicting people going to watch Bolton Wanderers at Burnden Park, the painting sold at auction in 1999 for the then record price for a Lowry of two million pounds.

Lowry was always interested in the places where people came together – a football match, a bandstand in the park, playgrounds, fairs, the seaside – anywhere where crowds gathered. Many such paintings are on view here. ‘Piccadilly Circus’, painted in 1960 and from a private collection, is a rare London view, while ‘Coming Out of School’ (1927) is not a depiction of a particular place, but is based on recollections of a school seen in Lancashire.

Most of my land and townscape is composite. Made up; part real and part imaginary […] bits and pieces of my home locality. I don’t even know I’m putting them in. They just crop up on their own, like things do in dreams.

In 1939, John Rothenstein, then Director of the Tate Gallery, visited Lowry’s first solo exhibition in London and later wrote: ‘I stood in the gallery marvelling at the accuracy of the mirror that this to me unknown painter had held up to the bleakness, the obsolete shabbiness, the grimy fogboundness, the grimness of northern industrial England.’

‘Lancashire Fair, Good Friday, Daisy Nook’ (1946) depicts visitors at the annual Easter Fair at Daisy Nook, a rural beauty spot on the River Medlock near Oldham. Echoing Howard Jacobson’s words, Lowry’s figures intermingle with each other, yet remain strangely isolated. Lowry once said: ‘All my people are lonely. Crowds are the most lonely thing of all’

LS Lowry: Lancashire Fair, Good Friday, Daisy Nook, 1946

‘Going To Work’ is a 1959 watercolour. Lowry painted only a small number of watercolours. This picture returns to one of his favorite themes: a swarm of workers funnelling towards the factory gates to start their working day, against a landscape of terraced houses, looming structures and smoky chimneys

I wanted to paint myself into what absorbed me […] Natural figures would have broken the spell of it, so I made my figures half unreal. Some critics have said that I turned my figures into puppets, as if my aim were to hint at the hard economic nescessities that drove them. To say the truth, I was not thinking very much about the people. I did not care for them in the way a social reformer does. They are part of a private beauty that haunted me. I loved them and the houses in the same way: as part of a vision.

Something I didn’t know was that from 1942 to 1945 Lowry was an Official War Artist. Though he produced very few works, there is one striking painting in this exhibition – ‘Blitzed Site’ from 1942, in which a lone figure stands amidst the ruins of what is probably his home, staring stunned at the shattered remains.

Another interesting work is ‘The Lodging House’, painted in 1921, and perhaps revealing something of the influence of Adolphe Valette, his tutor when he attended evening classes at Manchester Municipal College of Art in the years before the First World War. A note informs that this was the first work Lowry sold – to a friend of his father for £5.

The exhibition offers a rare chance to see several works from private collections – including ‘Election Time’ (1929), ‘The Orator’ (1950), and ‘Punch and Judy (1943).

‘After the Fire’ (1933) is another painting from a private collection. It depicts the aftermath of the destruction of a mill by fire, and stands alongside other ‘incident’ paintings such as ‘The Removal’ (an eviction) or ‘An Accident’ (actually a suicide) and ‘A Fight’ (1935).

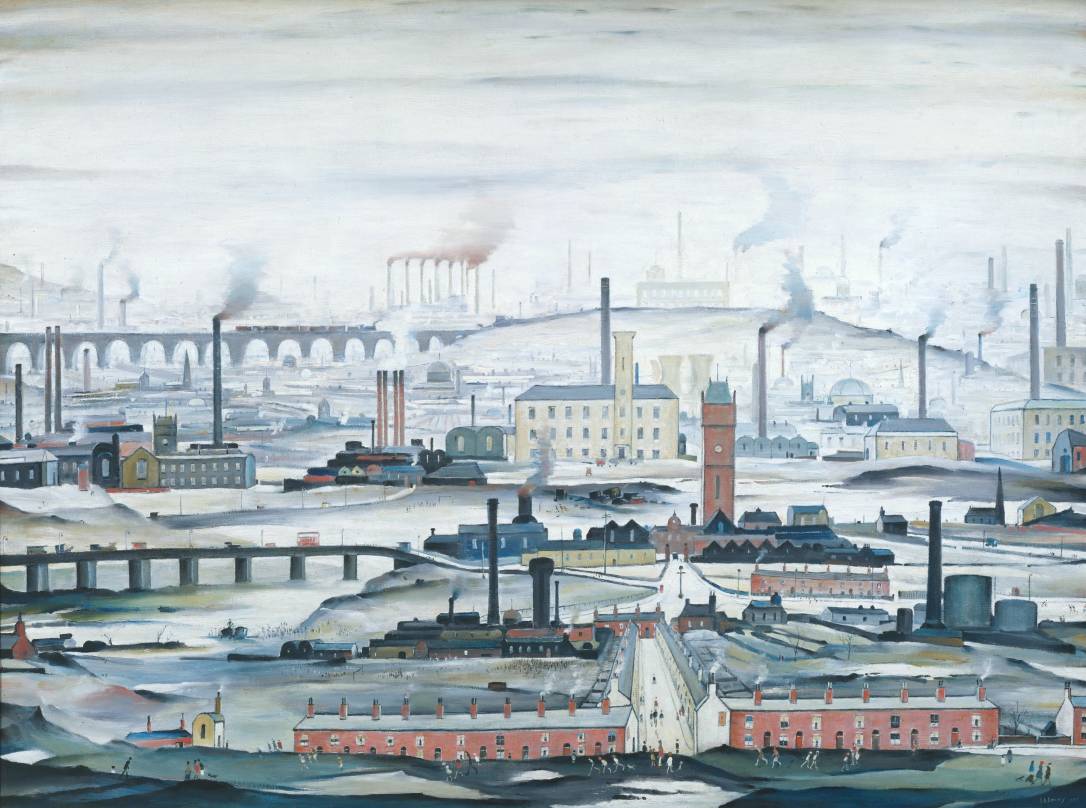

‘The Pond’ (1950) is one of Lowry’s largest works, one which he considered to be his finest industrial landscape. It contains many features typical of Lowry’s work – smoking chimneys, terraced houses and his ‘matchstick’ people who mill about in the city streets and open spaces.

In a letter to the Tate in 1956, Lowry wrote:

The idea originated in the Rochdale area, but it is not meant to represent a particular spot. This is a composite picture built up from a blank canvas. I hadn’t the slightest idea of what I was going to put in the canvas when I started the picture but it eventually came out as you see it. This is the way I like working best.

On the right, in the middle distance, is Stockport Viaduct:

It’s with me all the time – somewhere, just waiting to appear. It haunts me.

The viaduct appears again in ‘The Viaduct’ (1954), typical of many of his later urban landscapes from which people have largely been removed, leaving only stark, empty panoramas, with perhaps an isolated building – in this case, a Greenall’s pub, the White Star Hotel. This painting was once owned by Alec Guinness. In his Diaries, he recalled a journey through deserted city streets where ‘a few thin clerks … hunched themselves against bitter wind, walking stifflyand alone … like the figures in a Lowry industrial landscape’. Other works of this kind include ‘Derelict House’ (1952) and ‘The Waste Ground’ (1949).

There are rural landscapes, and seascapes, too – mainly, though not exclusively painted in the post-war years. Not many of those are included in this exhibition, but notable works of this kind on display include ‘A Landmark’ from 1936, ‘Seascape’ from 1943 and ‘The Sea’ painted in1963.

‘Seascape’ originated following a trip to Anglesey in the early 1940s. Lowry later spoke about the painting’s origins and its psychological significance:

I couldn’t work … a month after I got home I started to paint the sea. But a sea with no shore and nobody sailing on it … Look at my seascpes, they don’t really exist you know, they’re just an expression of my own loneliness.

After the death of his mother in 1939, Lowry lived alone for almost 40 years.

In later paintings such as these there is a sense of infinite empty space. All signs of human activity are removed. Only solitary buildings or monuments suggest the presence of people. But, Lowry is no Turner – his landscapes and seascapes do not record the effects of light or weather. The light is usually cold and even. Hills and fields are reduced to simple repeated patterns.

The sea especially was a source of inspiration. In the 1960s Lowry was a regular visitor to the northeast, staying at the Seaburn Hotel in Sunderland in a room from which he could see the North Sea.

It’s all there. It’s all in the sea. The battle of life is there. And fate. And the inevitability of it all. And the purpose.

At the very end of the exhibition was a painting I had never seen before – ‘Flowers in a Window’, completed in 1956. It seemed very different to everything that went before.

See also

- LS Lowry on Your Paintings (BBC)

- Adolphe Valette: Pioneer of Impressionism in Manchester

- Lowry in Stockport

- The proud provincial loneliness of LS Lowry: transcript of the annual LS Lowry lecture delivered by Manchester-born novelist Howard Jacobson in 2007 (part 1)

- The loneliness of LS Lowry: Howard Jacobson’s lecture, part two

- 2008 LS Lowry Lecture by Stuart Maconie (audio)