We approached Forest, Field & Sky: Art out of Nature, last night’s documentary on BBC Four presented by Dr James Fox, with great anticipation since its subject was a form of art that has inspired us both – and provided the subject of many blog posts here. Fox didn’t disappoint, focussing on just a few brilliant examples of what is often labelled Land Art – art that is made directly in the landscape, from natural materials found in situ, such as rocks, tree branches or ice. Travelling across Britain, he discussed artists whose work explores our relationship to the natural world such as David Nash, Andy Goldsworthy, Richard Long, and James Turrell, in some cases watching the artist in the process of creating a new work. Continue reading “Forest, Field & Sky: Art out of Nature”

Tag: Charles Jencks

The Garden of Cosmic Speculation

We’re driving north to the Scottish borders to visit the Garden of Cosmic Speculation, designed by Charles Jencks and open on just one day each year. The road takes us past Lockerbie, which lies some miles south of Jenck’s garden. There are unavoidable thoughts. In the book he wrote about the making of the garden, Jencks recalled the December evening in 1988 that imprinted the name of an unassuming town in global consciousness:

Maggie [his wife] went out to speak with Alistair’s wife, Frances. As they were walking in the kitchen garden Maggie saw the sky light up behind Frances’ head, in a great yellow and red ball of fire. More extraordinary than this explosion was the way it reached a peak and then suddenly imploded as if sucked into a vacuum cleaner and then the eerie silence of many seconds – Lockerbie is twelve miles away – followed by the roar of the earth. […]

Lockerbie has still not got over the tragedy of that evening, one that has turned it into a global name for the sudden, arbitrary nature of the catastrophe. Although the wreckage has been expunged and the visual scars healed, the citizens of the town are still marked by this fateful event. Everyone carries the memories of it – and subsequent actions and media coverage – in the back of their mind like a constant bad dream.

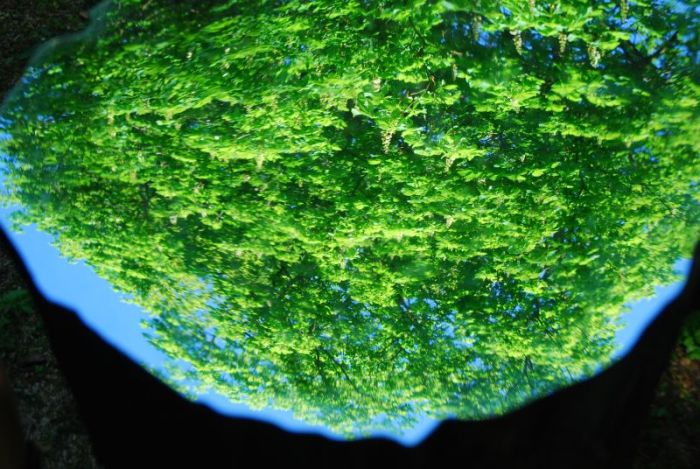

During a glorious two days in the Borders, beneath cloudless skies as an extended spell of high pressure continues, my thoughts would sometimes be drawn back to that event: the clear blue skies revealed the constant presence of con trails (above, over the River Nith below Portrack House) as planes regularly traversed the international flight path overhead. By strange coincidence, we returned home to news of the NATO bombing of Gaddafi’s compound that left his youngest son and three of his grandchildren dead, and of the American special forces action resulting in the death of Osama Bin Laden. This is how we have lived in the 21st century: distant turbulence intruding upon private pleasures.

The garden that Charles Jencks, an American-born landscape architect and historian, has developed at Portrack House has been inspired by questions of modern science and the laws of nature. The themes explored include the science of complexity and chaos, fractals, black holes and DNA, and concepts of space and time. These themes are represented by the extensive manipulation of the landscape and siting of individual sculptures and forms. The entire 30 acre site is itself a deliberate, considered sculpture:

The Garden of Cosmic Speculation is a landscape of waves, twists and folds, a landscape pattern designed to relate us to nature through new metaphors presented to the senses.

– Charles Jencks

The garden is situated at Portrack House, just outside the village of Holywood in Dumfries and Galloway, and was established by Charles Jencks and his late wife Maggie Keswick, whose family had owned the property for generations. After Maggie was diagnosed with inoperable cancer in 1993, the couple founded the network of Maggie’s Cancer Caring Centres that has continued to grow and develop since her death in 1995. The annual opening of the garden helps raise money for the Maggie’s Centres.

This is not a plantsman’s garden, but rather harks back to an earlier time when gardens were built to represent themes and ideas, rather than what is now generally considered to be their purpose – as a horticultural display. The garden is a landscape that celebrates the new sciences of complexity and chaos theory and consists of a series of metaphors exploring the origins, the destiny and the substance of the Universe: a celebration of the universe and nature, both intellectually and through the senses. The greenhouse roof is decorated with 12 equations that throw light on the laws of the universe. And the garden’s most prominent feature is the Universe Cascade (top), symbolically tracing the story of life over 15 billion years.

The garden began to take shape when the couple dug out a lake for their children to swim in, sculpting the resulting mound of earth in a double helix – the basic form of DNA – and calling it the Snail Mound. Visitors in 2011 entered the garden at the point of Jenck’s newest creation – the Rail Garden, created alongside the resonant red of the new railway bridge over the river Nith.

The rail garden features an engine pulling metal plates which celebrate the leaders of the Scottish Enlightenment, such as Andrew Carnegie, Robert Burns and the scientist Mary Somerville.

Below is the Willowtwist, a structure made from one single long sheet of aluminum, cut and split twice to form a series of intertwined loops, reminiscent of David Nash’s living Ash Dome.

The centrepiece of the garden is undoubtedly the complex of sinuous waveforms created by the Snail Mound, the Snake Mound and their related lakes. Jencks writes:

Curved and counter-curved shapes are structural and often found in nature, for instance in the meander of a river. Waveforms underlie so many natural activities: sea waves, of course, and sand forms left by the incessant waves on the ocean beach; the vortices caused by pulling a solid object through stationary liquid; the swirls of air currents where warm and cold air meet; and the rock curls evident in mountains, a result of a long, slow geological process of movement.

The DNA Garden is dominated by the silver aluminum curves of the double helix, while embedded in the paths are various codes and symbols. The garden celebrates the five senses, as well as the sixth sense of scientific intuition, called by Einstein fingerspitzengefuhl, that feeling at the tips of one’s fingers.

The Universe Cascade emerges from a terrace at the back of the house, looking, with its brilliant white architecture, like something that might have originated in New Mexico or the canyons of Los Angeles. Actually, it should be read from bottom to top, a cascade of steps each representing a ‘jump’ in the development of the universe, beginning at the beginning of time 12-13 billion years ago in a ‘hidden mystery conveyed by steps descending into a reflective, murky surface of water the depth of which is beyond seeing’.

With the creation of man, the principle of beginning came into the world – which, of course, is only another way of saying that with the creation of man, the principle of freedom appeared on earth….It is the nature of beginning that something new is started which cannot be expected.

– Hannah Arendt

Beyond the house is a sweep of meadow that leads to Crow Wood and the Nonsense. Here, on the Black Hole Terrace, a 20th century sort of ha-ha has been created, incorporating forms that act as a metaphor for bending of space and time in the vortex around a black hole.

Speaking of the ideas that underpin the garden, Charles Jencks has said:

Over several years I have worked on a Scottish landscape called, immodestly, the Garden of Cosmic Speculation, speculating with scientists and others on the fundamental laws and forces behind nature and what they might mean to us. Using growing nature to conjecture on what is basic to the Universe is an old practice common to gardeners, but it raises some unlikely questions.

Most people understand a big distinction between living nature and the laws of nature, that is, organic growth and electromagnetism, and they do not reflect that in a garden as elsewhere the latter may underpin the former. Furthermore, gardens of the last hundred years are for pleasure and relaxation, games and flowers, and not a place for public art.

My late wife Maggie and I started work on this garden around her family home in 1988 and slowly, area by area, it has grown into a landscape with about twenty areas dedicated to the fundamental units of the Universe: a Black Hole Terrace for dining on in the summer months; a DNA Garden of the Six Senses; the Quark Walk; the Universe Cascade and so on. Each insight into deep nature, many of which are recent, becomes translated into nature and sculpture. Landform is my generic name for this genre that cuts across art, landscape, architecture and the customary categories, and there must be something like twenty-five of them throughout the garden. Some landforms refer to theories of folding and fractals, others (when they fail) to catastrophe theory. As every gardener knows, the dialogue with nature is always two-way, and it pays to exploit the unintended consequences of nature’s acts.

Why dedicate a garden to the laws of nature? Partly because everybody relates, consciously or not, to the larger picture; we identify with nature and its various moods and states. … In the Garden of Cosmic Speculation I try out questioning metaphors, and this means that all design is really double design: that is, solving formal and functional problems, and coming up with new, appropriate metaphors (both visual and verbal). For instance, the Black Hole Terrace shows the space-time warps of super-gravity, the event horizons and rips in spacetime.

Public art must of course be understandable and moving, but I believe it also should engage with the basic insights on the cosmos.

Placing the Garden of Cosmic Speculation in the context of symbolic garden design in the past, Roman Krznaric has written:

Look around most of our own gardens today and you’re unlikely to find much symbolism. In fact, since around 1700 gardens in Europe have been largely devoid of allegory and metaphor. Instead gardens are more for pleasure and beauty. We aim to create harmonious combinations of flower colours and foliage textures. We want plants of different heights and shapes. We desire visual splendour in the garden throughout the year. The emphasis is on the senses, especially visual impressions. But this is not the only way to think about garden design…

The idea of symbolic garden design has its origins in ancient civilisations. Thousands of years ago the Persians invented the ‘Paradise Garden’. To enter the garden you would have to cross water channels, which represented the four rivers of heaven. Once inside you would find a profusion of fruit trees, symbolic of the fruits of the earth created by God. The most important contemporary example is Charles Jencks’s ‘Garden of Cosmic Speculation’ in Dumfriesshire, Scotland, which has a DNA garden that is taking symbolic garden design into the future. It contains a series of six cells and in each there is a different kind of idea, which is symbolised by the planting. ‘The planting is subordinate to the design,’ he says, ‘but completes it and fills it out.’