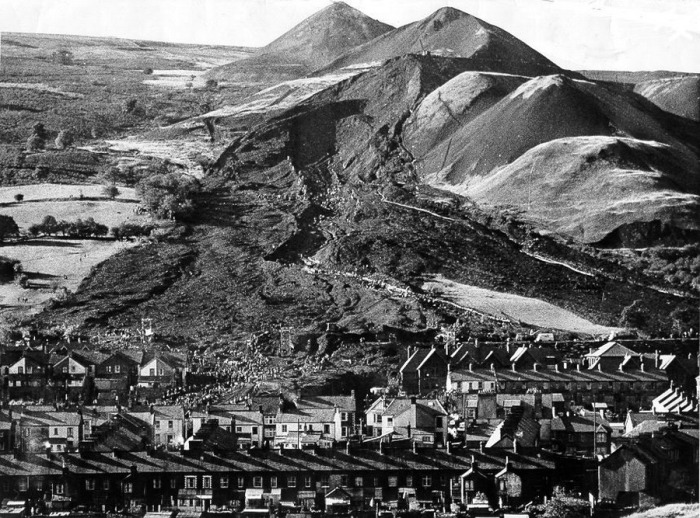

Fifty years ago today, on 21 October 1966, at 9.15 in the morning, the children of Pantglas Junior School had just returned from morning assembly to sit at their desks in their classrooms when spoil tip no. 7 tore down the mountainside, taking just five minutes to smash through houses and the school, burying everything in its path in a sea of thick, black mud. By that evening, as miners from the nearby pits toiled under arc lights, scrabbling with their bare hands at the slurry, the village of Aberfan knew that 187 souls were lost, 116 of them children. A generation had been wiped out.

I kept a diary in 1966, and looking at it now I see what a powerful impact the Aberfan disaster had on me. 18 years old at the time, I shared the grief, and then the growing anger of the whole nation at what, it soon became apparent, was not a tragic accident but the disastrous consequence of managerial insouciance – and of class attitudes which had always allowed those comfortably off and far from mines or factories to ignore the injustice and hardship imposed on those whose labour creates the nation’s wealth.

Many, like me, saw this as yet another example of the price of coal: the most compelling part of the O-level History syllabus I studied a year or so earlier was the story of 19th century working-class resistance to exploitation by the factory- and mine-owners (such as labour by children as young as five in the pits), and the inspirational movements for reform, from the Chartists to the new trade unionism of the late 19th century and the formation of the Labour party. The central part played by miners, their trade union, and leaders like Keir Hardie in the working class movement, demanding action to lessen the dangers of mine work and the reversal of injustices such as the 1900 Taff Vale judgement, were fresh in my mind.

Gaynor Minett, an eight-year-old who managed to escape, later recalled the moment when the mountain of slag hit Pantglas Junior School:

It was a tremendous rumbling sound and all the school went dead. You could hear a pin drop. Everyone just froze in their seats. I just managed to get up and I reached the end of my desk when the sound got louder and nearer, until I could see the black out of the window. I can’t remember any more but I woke up to find that a horrible nightmare had just begun in front of my eyes.

After the landslide there was total silence. George Williams, who was trapped in the wreckage, remembered:

In that silence you couldn’t hear a bird or a child.

Recently, on From Our Home Correspondent on BBC Radio 4, Felicity Evans drew parallels between the Aberfan disaster and the deaths at Hillsborough in 1989. What happened to Aberfan was ‘a human tragedy of the most brutal, sudden and shocking kind’ – the small mining village lost a school full of children in the few minutes it took coal waste tip number 7 to slide 500 feet down the hillside – but, like Hillsborough, it was also a scandal.

At the coroner’s hearing, one father on hearing his child’s cause of death given as asphyxia jumped up and shouted, ‘No sir, buried alive by the Coal Board.’ In response the coroner suggested that grief meant the man didn’t know what he was saying, but, as Felicity Evans remarked, ‘he was a grieving father but he knew exactly what he was saying – and he was right’. In the uproar at the inquiry a mother cried out, ‘He’s right. They killed our children.’

Tip no. 7 had been built on natural springs which made it inherently unstable – the National Coal Board at first denied knowledge of this, but as villagers themselves demonstrated at the public inquiry, the springs were shown on Ordnance Survey maps. We believed that with nationalisation we had got rid of the uncaring, exploitative attitudes of the private mine owners. But, not only did the NCB act like a private corporation, despite the enormity of the disaster the chairman of the NCB Lord Robens chose to go ahead with his investiture as Chancellor of the University of Surrey rather than travel to Aberfan, and he did not turn up there until the evening of the following day.

Worse followed. People from all over world contributed £1.75 million to the disaster fund – an extraordinary amount of money in the 1960s. Unbelievably, the Charity Commission opposed the plan for a flat rate of compensation to the bereaved families, instead suggesting that for payment to be made, parents should have to prove that they had been ‘close’ to their dead children, and were thus ‘likely to be suffering mentally’.

Meanwhile, Aberfan villagers lived in fear that tip no.4 and tip no.5 situated above tip no.7 might start to slide as well. The NCB refused to pay to remove them, and the Labour government wouldn’t make it pay. Instead the money was taken from the disaster fund – an act later described as unquestionably unlawful by charity law experts.

‘Like the Hillsborough victims,’ said Felicity Evans on Radio 4, ‘the people of Aberfan were let down by the very institutions that owed them a duty of care, and just like at Hillsborough those institutions sought to obstruct the search for truth and the solace it might provide.’

And, as with Hillsborough, justice was a long time coming. More than three decades later the Charity Commission apologised, and a Labour Government paid back to the Disaster Fund the money taken from it in 1966 by the NCB.

The conclusions of the tribunal set up to investigate the disaster were damning. The Coal Board was condemned for its failure to act on the concerns raised about the safety of the tips and the government was criticised. But the inquiry concluded that the disaster had been caused, not by ‘wickedness but ignorance, ineptitude and a failure of communication.’ No one was prosecuted, fined or dismissed and no one accepted responsibility for the tragedy.

Tucked into my 1966 diary is an article that I must have clipped from the Guardian that week. It is by Lena Jeger, the left-wing Labour MP who had worked as a columnist at the Guardian a few years before:

Distance is all. The distance of the tormented valleys of South Wales, where the womb of the earth is stuffed with rich curse-blessing coal, from the pastures of the Sussex downs where the houses are pretty and the worst threat of ugliness is the chain of skeletal pylons; the distance of mutilated Aberfan from the tidy suburbs of every prosperous town where gardens are kempt and people write to the council about the eyesore of an abandoned car in a sleek, fat street.

The distance, sometimes of a few yards, from the big warm habitations of the old coal-owners to the little terraces under the tumps where miners live. The shareholders were usually farther removed. The distance of a collier with a butty in his tommy bag from the expense account meals of urban restaurants. And, yesterday, the distance of Aberfan itself, the hillside of its cemetery wounded with the rawness of new trenches, from the funerals of the the other children men had killed on the other side of the world.

The morning news on the radio yesterday described how the funeral flowers were coming to Aberfan, a new hillock of fragile, fleeting beauty on the mountain of misery.

The next itm was an expression of regret that American soldiers had mistakenly killed a number of civilians in Vietnam, including women and children, because of wrong information that they were Vietcong. When is a child ‘Vietcong’? Perhaps, like the children of Aberfan, when old enough to be killed by grown-ups. I do not know, but the chances are that those children, north of Saigon, were also buried yesterday. In the hot lands you cannot wait and watch around a little coffin in the parlour. If these distant bereaved families were Buddhists there will have been gay paper chains and noisy bands and mourners in white to push the little boats across the Lethe.

The rites are a world apart. But the barbed wire pain in the eyes from paralysed tears, the corrosive acid of grief flowing over the soft stone of minds bereaved, these are the same; only distance divides. Send a toy? Send a flower?

How can mankind absorb the massiveness of guilt? In Aberfan we shall try to find out whose fault it was, find a focus for the pointing fingers, a target for the angry arrows of grief. Whatever the official inquiry finds, it is all our faults. The leading articles that were not written until now; the unasked questions in the House; undrafted motions at the lodges and the party meetings; the acceptance of assurance while uneasiness stuck like a needle in the mind. But, above all, the uncaring of distant people. The citizens of Bath or Bournemouth would not accept quietly a mountain of slurry in their own backyards.

[…]

It is, of course, not new to kill children, neither in Vietnam nor in Wales. It was not until 1842 that Shaftsbury was able to get a bill through Parliament prohibiting little maggots of children under 10 from working below ground. If they were ten and a half nobody minded.

‘Their memorial,’ as it says in Psalm IX, ‘is cherished with them’. But this new memorial must not perish, though the flowers will fade on the mountain and the toys for the lonely little brothers will spill their stuffing and break their springs. Where else are we tolerant of danger, blind by usage to the threat of industry’s hideous detritus? Where is there an abandoned quarry, a disused factory not emptied of machines, a lonely broken crane? Everybody must look and shout. And there must be no sentiment. Men, women and children must all feel upon their skin the great dark eyes of final disaster.

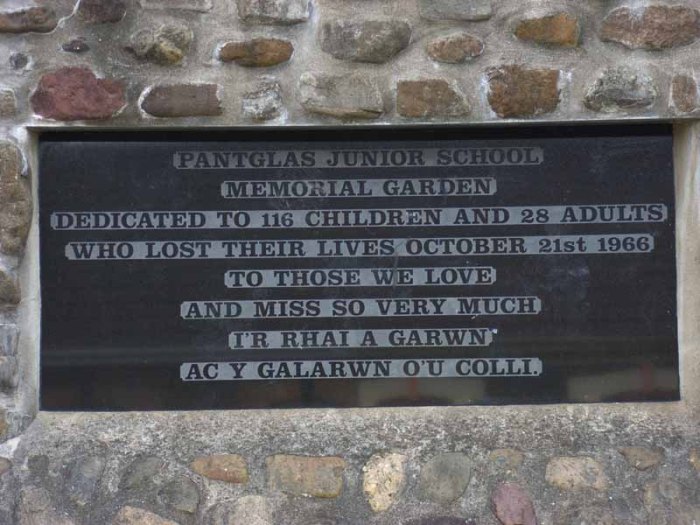

What remained of Pantglas school was demolished and a memorial garden now stands on the site. The mountain behind bears little trace of the old mine workings. Today the tips have gone and the mine has closed. About half the victims of the disaster were buried in the town’s cemetery.

Last week ITV screened a sensitive documentary about the Aberfan Young Wives’ Club that was adorned with a spare, elegiac score composed by the Manic Street Preachers frontman James Dean Bradfield who grew up 11 miles away. The film told how, a few months after the disaster, the women of the community – every one of them coming to terms with the grief of losing either one of more children of their own, or the bereavement of neighbours or relatives – began to meet and have never stopped, their weekly get-togethers continuing to this day. The group steadily grew in size and organised events, talks and trips, as well as supporting each other in their bereavement.

It was an exceptional film that ventured upon the sensitive terrain of a community which lost almost an entire generation in one terrible morning with great dignity and circumspection.

Sitting beside her surviving daughter Denise, Joyce Hughes, whose 9-year old daughter Annette died at the school, said simply:

She was one of these girls you’ve got to push to get ready for school, and I said to her, ‘Come on, you’re going to miss the bus.’ I said, ‘Go on now, quick now.’ so she was running down the street. She got to the top of the street and she waved.

And that was the last I saw of her.

The women spoke of the day that the slurry took their children with dignity. One who had fallen into a suicidal depression after the disaster spoke of how the weekly gatherings had given her the strength to carry on. No-one spoke about the disaster because, she said, there was no need. The grief has never gone away but the women learned how to got on with their lives and to regain an enjoyment of life through their own togetherness, and in some cases through having another child.

In The Fight for Justice on BBC 1 this week Huw Edwards presented an excoriating account of the NCB’s refusal to accept any responsibility for the disaster through reconstructions of cross-examinations at the Aberfan Inquiry. It’s available for another 3 weeks on BBC iPlayer.

This Sunday, BBC 4 will broadcast The Green Hollow, a ‘film poem’ by Owen Sheers commissioned to commemorate the disaster. In an introductory piece published in the Observer, Owen Sheers wrote about his visits to the village during the film’s preparation, and how many residents spoke of the kind of place Aberfan had been in 1966:

Many of the survivors I’d interviewed had spoken about the village’s vibrancy at that time. With full employment in the mine and local factories, its streets were thick with shops and tradesmen, boasting two butchers, two fishmongers and even two cinemas. The village’s cultural life was similarly active, with well-supported drama societies, bands and choirs and the swinging dance halls of Merthyr just down the road.

But, he continued, Aberfan is a very different place today:

Walking down Aberfan’s high street today I’d often found it difficult to imagine this version of the village. Over the past 50 years, as well as the disaster, Aberfan has also had to take all the other body blows inflicted upon the south Wales valleys by the late 20th century – the miners’ strike and closure of the pits, Thatcherism, unemployment, poverty, alienation, then Osborne’s austerity. The busy high street of traders is gone, and employment is largely elsewhere now, at the EE call centre in Merthyr, or further afield in Cardiff.

Owen Sheers’ poem will be only the latest in a long line of responses to the tragedy. Probably the first poetic response was ‘Aberfan : Under the Arc Lights’ by Keidrych Rhys, published in The Spectator a week after the disaster, on 28 October 1966:

Ask what was normal in green nature and its pain:

Will rain undermine our homes and us again?

Ask those scrabbling garden-breakers, the mountain sheep

Where are the classroom’s children? – and then weep.

O martyred town shorn of its crown of glory!

That dumpy matriarch scanning in our fury

For faces of first-borns in the two handed-bier;

All the elements of tragedy are here.

Waters of history still in midnight’s deep

Drip in Ceridwen’s cauldrons; rage eisteddfod, seep

Into the jagged stalactites of hearts’ hours.

Crushed out of life like paper-petalled flowers.

Ask courting couples whose coats took dust off the tips;

And hand back to the heavens stars on the future lips;

Children conceived in mist whose playground it had made.

Blame breeds guilt with blind anger in its road.

The whole bare drama played out as it looms

To a world-shared audience in their evening room;

One human chain of rescue under arc-light glare.

All the elements of tragedy are here.

In folk clubs in the late sixties, I would hear songs that expressed the anger that followed the sorrow and pity for Aberfan. Alex Glasgow, a pitman’s son from Gateshead and a passionate socialist, originally wrote ‘Close the Coalhouse Door’ for a BBC radio programme. It later became the title song for the 1968 stage musical written with Alan Plater. He added the ‘bairns’ verse after the Aberfan disaster:

Close the coalhouse door, lad. There’s blood inside,

Blood from broken hands and feet,

Blood that’s dried on blackened meat,

Blood from hearts that know no beat.

Close the coalhouse door, lad. There’s blood inside.

Close the coalhouse door, lad. There’s bones inside,

Mangled, broken piles of bones,

Buried ‘neath a mile of stones,

And there’s no-one there to hear the moans.

Close the coalhouse door, lad. There’s bones inside.

Close the coalhouse door, lad. There’s bairns inside,

Bairns that had no time to hide,

Bairns who saw the blackness slide,

Oh, there’s bairns beneath the mountainside.

Close the coalhouse door, lad. There’s bairns inside.

Close the coalhouse door, lad, and stay outside.

For Geordie’s standin’ on the dole

While Mrs Jackson, like a fool,

Complains about the price of coal.

Close the coalhouse door, lad, and stay outside.

The Unthanks sang Close the Coalhouse Door in 2011 on their album Last:

Leon Rosselson wrote his song ‘Palaces of Gold’ in response to news of the disaster at Aberfan. It appeared on his 1968 album A Laugh, a Song, and a Hand-Grenade:

If the sons of company directors,

And judges’ private daughters,

Had to got to school in a slum school,

Dumped by some joker in a damp back alley,

Had to herd into classrooms cramped with worry,

With a view onto slagheaps and stagnant pools,

Had to file through corridors grey with age,

And play in a crackpot concrete cage.

Buttons would be pressed,

Rules would be broken.

Strings would be pulled

And magic words spoken.

Invisible fingers would mould

Palaces of gold.

If prime ministers and advertising executives,

Royal personages and bank managers’ wives

Had to live out their lives in dank rooms,

Blinded by smoke and the foul air of sewers.

Rot on the walls and rats in the cellars,

In rows of dumb houses like mouldering tombs.

Had to bring up their children and watch them grow

In a wasteland of dead streets where nothing will grow.

I’m not suggesting any kind of a plot,

Everyone knows there’s not,

But you unborn millions might like to be warned

That if you don’t want to be buried alive by slagheaps,

Pit-falls and damp walls and rat-traps and dead streets,

Arrange to be democratically born

The son of a company director

Or a judge’s fine and private daughter.

On YouTube I found this excellent short video documentary, produced by Rachel Evans in 2006 as a college project:

The photograph at the head of this post is by the Magnum documentary photographer David Hurn who grew up in Wales. It came to be regarded as one of the iconic photographs of the Aberfan disaster. As Jo Mazelis puts it in an interview with Hurn for the Welsh Arts Review: ‘Two boys stand in the foreground with the destroyed school before them. It creates a narrative that suggests these boys are survivors, reminding the viewer of the youth of those lost.’

Read more

- Aberfan 50 years on: how best to remember the tragedy? Guardian feature by Owen Sheers on his memorial poem The Green Hollow

- Extracts from The Green Hollow

- The Aberfan disaster: web pages set up as part of a project to catalogue and conserve an archive of material relating to the disaster held at Merthyr Tydfil and Dowlais libraries

- The Aberfan disaster: John Humphrys, Huw Edwards and a survivor recall the 1966 tragedy (Radio Times)

- Aberfan: how a ‘gullible and deferential’ press failed the victims

- This Is Tragedy: British Pathé newsreel from 1966

- Aberfan 1966: short clip from BBC Timewatch documentary in 2011

Reblogged this on Passing Time and commented:

‘In that silence…’ A powerful and moving commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Aberfan disaster, from That’s How the Light Gets In.

Thanks, Cath, for another reblog. I always appreciate it.

Those ‘know where you were’ moments. The Kennedy assassination. Then Aberfan. I was a young undergraduate by this time, absorbed by the novelty of university life, not yet fully radicalised. Yet the shock was huge; the ‘how could it happen’,enduring. And of course – no surprise – the cover-up. No one to blame. Nothing to see. Move along now. Pfft.

Just look at that mountain of spill turned to slurry, administered by a National Coal Board. Public ownership? Accountability? Not then. Not now

Just watch the admirable Huw Edwards documentary to see how public bodies failed the villagers – a lethal cocktail of self-seeking, arrogance, stupidity, personal animosities, and contempt for ordinary people. The heroes were those who clawed at the rubble – and the lawyers who fought the NCB evry inch of their contemptible way at the inquiry. For Liverpudlians it’s shockingly familiar.

Fine piece, Gerry. My dad was from Mountain Ash, the nearest town to Aberfan, in the next valley. Still have relatives there but I’ve never heard them mention the tragedy; perhaps too painful. Beyond impressed by your teenage diary by the way.

Well I never knew you had Welsh origins.My diary was strange (revealing perhaps): hardly anything personal in it, but rather a record of the political developments of the time.I was determined to be a journalist. But I was grateful for it – and especially the Lena Jeger cutting – when it came to writing this post.Wish I’d continued to keep a diary through all the intervening years. The last entry was the day I left for uni.

Lovely piece, Gerry. I’ve shared on social media. I’m from the Eastern Valley just over from Aberfan (near Blackwood where the Manics come from). I was a baby when it happened; but I have vivid memories over 10 years later of the slag heaps of South Wales. In fact I thought there were two kinds of mountains, some green and some black, never realising what lay under the black ones. Despite the Aberfan disaster it was a very long time before anything constructive was done. I remember speaking in university to a friend from Surrey about slag heaps, and she didn’t have a clue what I was talking about. We could have been from a different planet….

Thanks, Margaret, I appreciate your comment and you sharing the post. I had conversations like that at uni in the sixties when those of us from working-class homes were very much in a minority. ‘Distance is all’, as Lena Jeger wrote in her article.

Hi Gerry – I live abroad now but was visiting the UK, South Wales in particular, during this year’s (2016) anniversary. I was driving through the area and happened to listen to a phone in on the BBC, with contributions from witnesses: residents, rescuers, bereaved family members… It was incredibly moving and I sat in a car park, unable to switch off. The tragedy resonates deeply with me (I’m English but my great-grandfather was a miner in the valleys in the early 1900’s). The attitudes of the “powers that be” at the time are on the one hand shocking and almost unbelievable, but yet somehow so sickeningly familiar and current.

Thank you for your writing, on everything. I sorely miss the intimacy of connections between geography, society, history and politics that infiltrate life in the UK and that you illuminate so well.

Andrew