There was another fascinating exhibition on at the British Library when I went there last week to see West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song. The Alice in Wonderland exhibition, on until April 2016, marks the 150th anniversary of the publication of Lewis Carroll’s story. I recently finished reading The Annotated Alice, a deeply engrossing labour of love edited by Martin Gardner, so I was irresistibly drawn to a captivating exhibition that explores the enduring attraction of Carroll’s book.

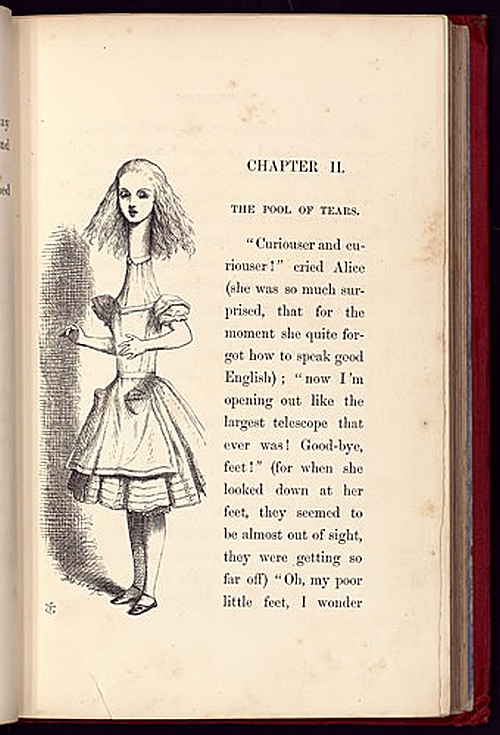

The show begins with its star attraction and one of the British Library’s most loved treasures – Charles Dodgson’s original handwritten manuscript of the story – then entitled Alice’s Adventures Under Ground – which also turns out to be illustrated with his own pen and ink drawings.

`I know something interesting is sure to happen,’ she said to herself, `whenever I eat or drink anything; so I’ll just see what this bottle does. I do hope it’ll make me grow large again, for really I’m quite tired of being such a tiny little thing!’

It did so indeed, and much sooner than she had expected: before she had drunk half the bottle, she found her head pressing against the ceiling, and had to stoop to save her neck from being broken. She hastily put down the bottle, saying to herself `That’s quite enough – I hope I shan’t grow any more – As it is, I can’t get out at the door – I do wish I hadn’t drunk quite so much!’

Alas! it was too late to wish that! She went on growing, and growing, and very soon had to kneel down on the floor: in another minute there was not even room for this, and she tried the effect of lying down with one elbow against the door, and the other arm curled round her head. Still she went on growing, and, as a last resource, she put one arm out of the window, and one foot up the chimney, and said to herself `Now I can do no more, whatever happens. What will become of me?’

Dodgson’s manuscript is the gem at the heart of this exhibition, and with the crowd that it drew it was quite difficult to get a good look at it. There is much more, however, much more to hold one’s attention as the exhibition goes on to explore the different ways in which generations of illustrators, artists, musicians, film makers and designers have interpreted the story and characters of the two Alice books over the past 150 years.

It’s clear – obvious really – how each new illustrated edition of the story often mirrors the period in which it was created, from Charles Robinson’s art nouveau version and Arthur Rackham’s splendid interpretations (both from 1907, the year that the original copyright ran out) or Mabel Lucie Attwell’s cute rosy-cheeked Alice of 1910 – to Salvador Dalí’s surreal and psychedelic lithographs (one hundred per cent Dali, zero percent Carroll) and Peter Blake’s watercolours for Through the Looking Glass, both produced in 1969.

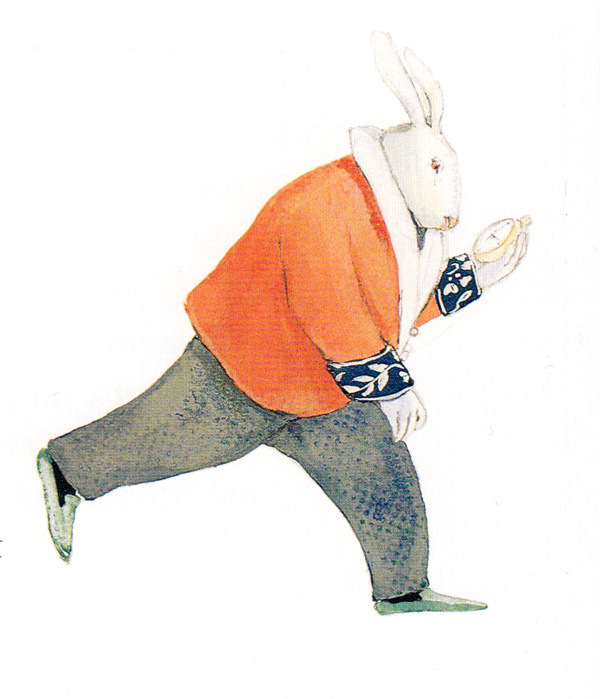

Peter Blake had been originally commissioned to illustrate the Alice books in 1969, but the cost of producing the books was considered too high; the eight watercolours were eventually issued as limited edition screen prints in 1970.

Perhaps the best example of an artist mirroring his own society in his Alice illustrations is Ralph Steadman’s illustrated Alice in Wonderland, published in 1972 to high acclaim.

In Steadman’s vision the White Rabbit is a bowler-hatted commuter, late for his train, while the playing cards are proletarian, flat-capped workers holding union cards. The illustrations are simply but exquisitely rendered in black pen and ink with Steadman’s characteristic use of line and his eye for detail.

The British Library recently acquired an archive of Mervyn Peake’s work, including the illustrations he made for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass in 1946. They are on show, along with Leonard Weisgard’s superb illustrations for his 1949 edition.

It may be that Mervyn Peake’s recent experience sketching the horrors he had witnessed in the liberation of Belsen were reflected in his interpretation of some of the more sinister aspects of Carroll’s Alice stories. First published by in Sweden in 1946, and then in the UK publication in 1954, they include a definitely fearsome Cheshire Cat.

Rebecca Sinkler once remarked in the New York Times:

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a sacred text. But sacred texts invite – require, even – reinterpretation.

That was in 1999, when Sinkler was reviewing a new illustrated edition by the Austrian artist and acclaimed children’s book illustrator, Lisbeth Zwerger, another highlight of the British Library exhibition. In her review of Zwerger’s book, Rebecca Sinkler observed:

Zwerger never sugar coats Alice’s experiences. Her heroine is thoroughly contemporary in dress and demeanour, with the kind of unblinking, somewhat veiled expression one sees on the faces of certain post-modern little girls. One of Zwerger’s most effective tools is her skewed, fractured point of view.

Many images appear oddly cropped or seen from an offbeat angle or perspective – all brilliantly appropriate to Alice’s newly fractured universe, her unpredictable spurts of growth and shrinkage.

In the image which also serves as the cover of the book, Zwerger portrays the Mad Hatter’s tea party as a collection of individuals, isolated from one another, who appear to be present and yet not there at the same time. Alice, at the head of a table covered by a pristine white linen cloth on which various objects stand in similar isolation, stares at the pocket watch that the March Hare is about to lower into his cup of tea. The Hare gazes out towards the reader while the Mad Hatter to his right, wearing a hat box rather than a hat, stares intently at a black cap. Between them the Dormouse sleeps. Across the table, an empty red mug is placed in front of an empty green chair. Zwerger has brilliantly managed to present a familiar scene in a way that is both recognisable, yet strangely disturbing.

Rebecca Sinkler makes this observation about Zwerger’s portrayal of the moment when Alice falls down the rabbit hole, noting that its not a literal transcription of the fall, but one that takes us under the skin of childhood anxiety:

Zwerger who takes it under her skin. Her diagram of the downward passage hints at the disgusting and surreal – a rat’s hindquarters, a roach, an odd (and contemporary-looking) bottle cap and an animal skull. She perfectly conveys Alice’s suppressed terrors. Any curious child will spend some time inspecting these repellent images.

I also liked Zwerger’s take on a design that began in Charles Dodgson’s original hand-written manuscript: ‘the long and sad tale of the Mouse’. It reminded me of just one example of the fascinating notes that form the bulk of The Annotated Alice, edited by Martin Gardner, that I read recently.

In his original design, Dodgson lettered an entirely different verse to form the mouse’s tail to that which appeared in Tenniel’s illustration for the published book. Gardner reckons that the original poem is far more appropriate, since it fulfils the mouse’s promise to explain why he hates both dogs and cats. He also observes that this technique – dubbed ‘art chirography’ – in which words are formed so as to convey a visual impression of their ideas has since become common in the lettering of advertisements, book jackets, titles of magazine stories, cinema and TV titles, and so on.

It’s more than 50 years since Martin Gardner published the first edition of The Annotated Alice. More Annotated Alice followed three decades later. I read his third dissection of trivia, mathematical riddles and wordplay, now published by Penguin as The Definitive Edition. Martin Gardner died in 2010, just four years shy of his hundredth birthday, and by then established as one of the world’s leading authorities on Lewis Carroll. It was Gardner who first decoded many of the mathematical riddles and wordplay that lie ingeniously embedded in Carroll’s two classic stories, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass.

The Annotated Alice contains both books, with the notes printed in smaller text in columns to the right and left of each double-page spread. This means that it’s easy to glance at the annotations without being too distracted from the original text. For me, this was the first time since childhood that I had read Carroll’s books, and Gardner’s labour of love made me realise just how incredibly clever Carroll’s nonsense tale is – and how much there is for an adult reader to relish.

This is the place to come if you want to know how the Cheshire Cat got its grin, or what made the Mock Turtle cry, or learn about the Anglo-Saxon provenance of the ‘Jabberwocky’ poem. In the first edition Gardner invited readers to submit answers to the Mad Hatter’s riddle ‘Why is a raven like a writing-desk?’, and he has selected some of the best for our enjoyment.

Among the many pleasures there is Gardner’s discovery of the long-forgotten Victorian poetry that Carroll parodied brilliantly in the books – and, for me at least, the revelation that the whole of Through the Looking Glass is an elaborate chess game which Gardner carefully elucidates (along with many more of Carroll’s mathematical riddles).

And then there’s the whole business of mirrors. Gardner recounts a memory of another Alice, Carroll’s distant cousin Alice Raikes, of the part she played in suggesting the mirror motif. This is how she told the story in the London Times, January 22, 1932:

As children, we lived in Onslow Square and used to play in the garden behind the houses. Charles Dodgson used to stay with an old uncle there, and walk up and down, his hands behind him, on the strip of lawn. One day, hearing my name, he called me to him saying, “So you are another Alice. I’m very fond of Alices. Would you like to come and see something which is rather puzzling?” We followed him into his house which opened, as ours did, upon the garden, into a room full of furniture with a tall mirror standing across one corner.

“Now,” he said, giving me an orange, “first tell me which hand you have got that in.” “The right,” I said. “Now,” he said, “go and stand before that glass, and tell me which hand the little girl you see there has got it in.” After some perplexed contemplation, I said, “The left hand.” “Exactly,” he said, “and how do you explain that?” I couldn’t explain it, but seeing that some solution was expected, I ventured, “If I was on the other side of the glass, wouldn’t the orange still be in my right hand?” I can remember his laugh. “Well done, little Alice,” he said. “The best answer I’ve had yet.”

I heard no more then, but in after years was told that he said that had given him his first idea for Through the Looking Glass, a copy of which, together with each of his other books, he regularly sent me.

There’s a wonderful passage in which Gardner enumerates just a few examples of the left-right reversals that pepper the book: Tweedledee and Tweedledum are mirror-image twins; the White Knight sings of squeezing a right foot into a left shoe; to approach the Red Queen, Alice walks backward; in the railway carriage the Guard tells her she is travelling the wrong way; the King has two messengers, ‘one to come, and one to go.’ He continues:

The White Queen explains the advantages of living backward in time; the looking-glass cake is handed around first, then sliced. Odd and even numbers, the combinatorial equivalent of left and right, are worked into the story at several points (e.g., the White Queen requests jam every other day). In a sense, nonsense itself is a sanity-insanity inversion. The ordinary world is turned upside down and backward; it becomes a world in which things go every way except the way they are supposed to. Inversion themes occur, of course, throughout all of Carroll’s nonsense writing. In the first Alice book Alice wonders if cats eat bats or bats eat cats, and she is told that to say what she means is not the same as meaning what

she says. When she eats the left side of the mushroom, she grows large; the right side has the reverse effect.

The book is a joy – as was the British Library exhibition. Although I’ve emphasised the illustrations on display, visitors can also see the first film adaptation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, a silent film from 1903 by Cecil Hepworth and Percy Stow. There are examples of early Alice memorabilia including wooden figurines, tea tins and a postage stamp case.

The exhibition reveals how, ever since the first editions illustrated by Tenniel, the story of Alice has been re-imagined and re-illustrated – yet all these different versions, despite reflecting their adaptation to changing times, have remained remarkably true to Carroll’s original story.

One pill makes you larger, and one pill makes you small

And the ones that mother gives you, don’t do anything at all

Go ask Alice, when she’s ten feet tall

And if you go chasing rabbits, and you know you’re going to fall

Tell ’em a hookah-smoking caterpillar has given you the call

And call Alice, when she was just small

When the men on the chessboard get up and tell you where to go

And you’ve just had some kind of mushroom, and your mind is moving low

Go ask Alice, I think she’ll know

When logic and proportion have fallen sloppy dead

And the white knight is talking backwards

And the red queen’s off with her head

Remember what the dormouse said

Feed your head, feed your head

Children’s literature of the mid-19th century was very much written with an instructive vein running through it – very moralistic, teaching children good behaviour and the social norms of the period. What’s interesting about Carroll’s book is that it is written with the children in mind and Alice is a believable child character. She meets a very strange group of characters but she remains quite unfazed. But children spend quite a lot of their lives meeting strange people in strange situations.

What makes the books eternally appealing is the way in which Alice makes the logic of the everyday, adult world seem nonsensical and absurd. As a teacher of logic, Lewis Carroll knew a lot about the struggle between the rational and the irrational: between the need to grow up and the desire to remain a child.

I think Frank Cottrell-Boyce was onto something, writing in the Guardian:

So why is Wonderland so much more than the sum of its marvellous parts? […]

Part of the answer is Alice – probably still the most feisty and inspiring of heroines. Surrounded by arbitrary authority, she insists on talking sense (“There’s plenty of room!” she says to the Mad Hatter). She refuses to be frightened or to keep her curiosity in check. We might be enchanted, but she never is. At the end of Wonderland, she rejects the very fiction that contains her (“You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”).

The logic of Wonderland is the logic of a bright child’s boredom – picking away at language, manners and stuffed specimens – while the adults drone on in the background. It’s an urgent reminder, in an age of instant digital distraction, of what a precious part of the creative process boredom really is.

We all come to Alice in different ways at different ages, in changed times. Concluding his review of the new edition of The Annotated Alice in The New Yorker in October 2015, Adam Gopnik wrote:

With all of its horizontal expansions, the new “Annotated Alice” fails to include what is perhaps the most widely disseminated, if hidden-in-plain-sight, of all Alice resonances. I mean the reproduction of the White Queen’s rising cry of “Better, better, better!” as the climax of the most successful of all Beatles singles, “Hey, Jude.” Lennon and McCartney’s obsession with the Alice books is familiar to all Beatlemaniacs. “I was passionate about ‘Alice in Wonderland’ and drew all the characters. I did poems in the style of the Jabberwocky. I used to live Alice,” John said once; Paul’s enthusiasm was equally intense: “Both of us loved Lewis Carroll and the Alice books.” … The Beatles singing Alice provides us, if not with a note, then at least with one more grin without a cat, a resonance without a reference. It may be odd not to find it in this compendious store of resonances . . . But then, who can be finished with Alice? We see her, sense her, hear her, everywhere.

In his prefatory verses for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll recalls that ‘golden afternoon’ in 1862 when he and his friend the Reverend Robinson Duckworth took the three Liddell sisters on a rowing expedition up the Thames:

In fancy they pursue

The dream-child moving through a land

Of wonders wild and new,

In friendly chat with bird or beast —

And half believe it true.

And ever, as the story drained

The wells of fancy dry,

And faintly strove that weary one

To put the subject by,

“The rest next time—” “It is next time!”

The happy voices cry.

Thus grew the tale of Wonderland:

Thus slowly, one by one,

Its quaint events were hammered out—

And now the tale is done,

And home we steer, a merry crew,

Beneath the setting sun.

Alice! A childish story take,

And with a gentle hand,

Lay it where Childhood’s dreams are twined

In Memory’s mystic band,

Like pilgrim’s withered wreath of flowers

Plucked in far-off land

It may be, as Martin Gardner suggests in The Annotated Alice, that in that last verse Carroll is suggesting to Alice that she should store these tales in her childhood memory, ‘the memory that when she becomes an adult, is like a withered bunch of flowers plucked in the far-off land of childhood.’ A few years before writing this poem, Carroll had photographed Alice with a wreath of flowers on her head.

See also

- ‘Alice’s Adventures Under Ground’, the original manuscript version of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: turn the pages of the British Library copy

- The influences on Alice in Wonderland: British Library article

- 150 years of Alice in Wonderland: article by Helen Melody, exhibition curator

- Who Can be Finished With Alice?: review of The Annotated Alice by Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker, October 2015

- The Annotated Alice: dyspeptic review by Will Self, New Statesman, December 2000

- Lewis Carroll’s Shifting Reputation: balanced assessment by Jenny Woolf in Smithsonian Magazine (‘His image as a man of suspect sexuality says more about our society and its hang-ups than it does about Dodgson himself. We see him through the prism of contemporary culture – one that sexualizes youth, especially female youth, even as it is repulsed by paedophilia.)

Hi Gerry FYI

I was really looking forward to reading your Alice Blog but unfortunately I couldn’t get it to download when I clicked the read more. As my other links seem to be working well I wonder whether the problem may be at your end. Blessings x

Date: Mon, 4 Jan 2016 19:15:06 +0000 To: debralittleboy@outlook.com

Hi Debra. It’s working fine on my PC and phone. It’s got a lot of images so it might be slow loading. Maybe reboot and try again? Good luck!

Gerry, excellent posting on “Alice” I didn’t know the exhibition was on. I think I got into Alice in my teens rather than childhood. Probably Grace Slick did it for me. The annotated Alice and Snark books fascinated me when first published by Penguin, again I think in the 60s. I have collected a few DVDs of assorted Alices,the Jonathon Miller version is a particular favourite, probably sums it up best for me. That DVD contains a copy of the first Alice film from 1900s. I also like a TV version Chanel 4 I think, with a young Kate Beckinsale of all people, which I videoed when bedridden twenty years ago. I must get hold of the latest ”annotated”. Radio 4 produced a Snark last week, over Christmas. Happy new year Bill Date: Mon, 4 Jan 2016 19:15:09 +0000 To: billmajor@hotmail.co.uk