The Chagall The Matisse Museum isn’t the only space dedicated to a great artist on the leafy hill of Cimiez overlooking the city of Nice. In 1973 the Chagall Museum was inaugurated, funded by the French state and designed partly by the artist himself. It now hosts the biggest collection of Chagall’s work anywhere in the world. We made our second visit to the gallery during our recent trip to Nice.

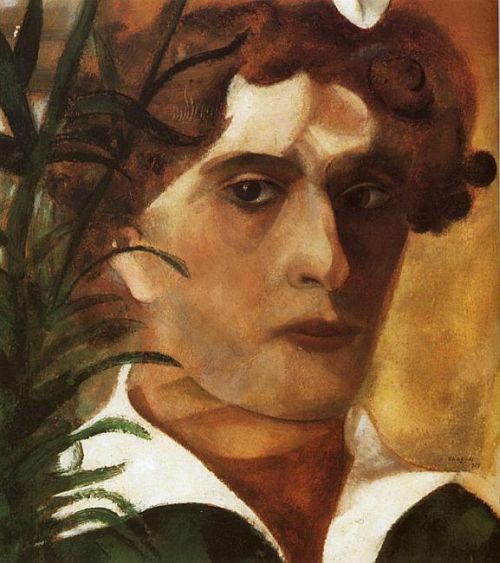

We arrived as the museum celebrates its 40th Anniversary with a special exhibition of Chagall’s self-portraits called Chagall in Front of the Mirror with over 100 paintings and drawings assembled to explore how his self portraits reflected Chagall’s personal life and struggles, and the times he lived through.

Chagall was a Russian-born Jew, who moved to Paris where he emerged as an early pioneer of Modernism, constantly refining his artistic style whilst exploring his personal and cultural identity in his work. Synthesizing elements of Cubism, Symbolism and Fauvism, his poetic, lyrical style culminated in the post-war years in a prolific output of paintings, stained glass windows and large-scale murals that are unique. On show permanently at the Chagall Museum are many stunning large-scale works from these later years.

Before revisiting these works, we looked at the temporary exhibition that focusses on Chagall’s self-portraiture. It begins with his examples of self portraits painted in a classic ‘artist at the easel’ style – painted in Paris around 1914. Even in these early, more formally composed portraits, Chagall’s depiction of himself is more stylized than realistic.

Realistic self-portraits became rarer from the 1930s – ‘as if the individualistic image of the self was gradually losing its reason for being’. In later years his self portraits gradually took on a more or less symbolic form, culminating in works crowded with animals, spirits and fantastical creatures in which Chagall would play either a leading or supporting role.

The only constant in Chagall’s self portraits, the exhibition’s narration suggests, was that he rarely depicted himself in a state of rest or meditative contemplation.

A section of the exhibition is devoted to Chagall’s double portraits – portraits of couples – that are a recurrent theme in his work. Many of theme date from the period 1915-20 which first saw him separated from his beloved Bella, then reunited with her and eventually married after his return to Russia.

Collectively, these paintings represent – in the words of the curators – ‘a celebration of the couple sanctified by marriage, the symbol of human love, reflection of divine love, echoing the story of Adam and Eve.’ Chagall would riff endless variations on this theme right through to the end of his life.

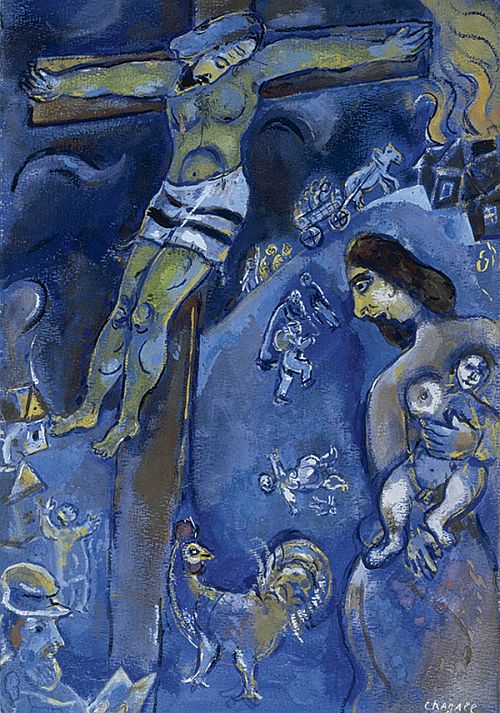

A striking section of the exhibition presents examples from an extraordinary series of paintings – beginning in the late 1930s and continuing into the early 1950s – in which Chagall depicts himself either with, or as, Jesus Christ. The recent Tate Liverpool exhibition Chagall Modern Master revealed how Chagall’s commitment to portraying Jewish history, fables and identities deepened after his return to his home town of Vitebsk during the First World War, responding in paint to the traumas of war and religious persecution in Russia. That exhibition told how, for Chagall, being an artist was both a secular and a spiritual calling through his embrace of his Jewish identity.

So, for me, the ‘crucifixion portraits’ in Nice represented a kind of bridge between the strong elements of Judaism in the Liverpool exhibition and the works on permanent display in the Chagall Museum, with their focus on subjects from the Bible. These works reflect a theme which came to dominate his art in the post-war period – an attempt to reconcile Judaism and Christianity within his art. In Self-Portrait with Wall Clock, the crucified Christ is comforted by a woman clothed in white bridal garments, while Chagall depicts himself as a painter with two heads branching out of the same body, one human and the other that of an animal.

In The Soul of the City, painted in 1945, Chagall portrays himself as the artist facing in two directions at the same time: looking back to the river of light that flows from his home town in Russia and from the teachings of the Torah; and facing the canvas on which he has painted Christ’s crucifixion.

For me, Christ has always symbolized the true type of the Jewish martyr. That is how I understood him in 1908 when I used this figure for the first time… It was under the influence of the pogroms. Then I painted and drew him in pictures about ghettos, surrounded by Jewish troubles, by Jewish mothers, running terrified with little children in their arms.

Chagall also described the act of painting Jesus as ‘an expression of the human, Jewish sadness and pain which Jesus personifies. …Perhaps I could have painted another Jewish prophet, but after two thousand years mankind has become attached to the figure of Jesus.’ In Persecution, 1941, a work in pastel, gouache and watercolour on paper, Christ is crucified amidst scenes of destruction, exile and death whilst a mother tries to save her child.

This exhibition text sums up the development of Chagall’s approach to self-portraiture in these words:

Chagall worked on the self-portrait more than any other subject in his very long career. In the traditional manner, it reflects his experiments with style and questions about his identity and role as an artist, to which he brought some new answers. It started as an assertion of his status as a painter, but, from 1915-17, quickly became a way of conveying a message that transcended him. His numerous canvases from 1907 to 1985 touched on all aspects of the self-portrait: frequently a portrayal of himself standing at his easel, holding a palette, or in his studio, and thus as an artist; less often, meditative portraits of a man gazing at himself; and an astonishing series of pictures of himself as Christ in the 1940s and 1950s.

But there are also many double portraits, in which he paints himself with his wife, a muse closely entwined with the artist, and disguised self-portraits, in which he takes a different form, often that of an animal. He also pops up in his other paintings, as if bearing witness to his own accomplishment. These very different portraits of himself enable the artist to embrace the world and all its kingdoms – the Hasidic Judaism of his childhood is not foreign to this vision of Creation – and to act as its spokesman.

His treatment of the self-portrait evolves over time: at first realistic, descriptive or staged in the manner of the old masters (influenced by Spanish painting or Rembrandt’s self-portraits), they gradually become more stylised, and the artist is recognisable not so much by his features as by his curly brown hair. Chagall shows himself as a painter, sitting in front of a canvas, the subject of which can usually be seen, thereby emphasising the subject of the painting as much as the painter as a subject.

The exhibition … shows how the self-portrait enabled Chagall to assert his place apart as a religious artist and invites us to think about the self-portrait as special way to gain access to the artist’s true self and the meaning of his work.

On 2 September 1944, Bella Chagall died at Cranberry Lake, New York state. Only a few weeks earlier, Chagall had completed the last of the ‘double portraits’ of himself and Bella: On the Road to Cranberry Lake. This is the most recent acquisition of the Chagall Museum and formed a moving conclusion to the special exhibition of portraits.

The painting features the motifs of flowers, a crescent moon, a street bordered by houses, and a couple that would haunt Chagall’s work from the 1910s onwards. It represents the spirit of Vitebsk with its lop-sided wooden houses, and of Bella, beloved wife, muse, and protector; angelic and divine, highly cultivated and a gifted actress. It represents the couple’s nostalgia in exile.

Having taken French citizenship in 1937, they had fled to the United States following the Nazi occupation. They settled in In New York, where Chagall’s paintings in the years of exile became full of new interpretations of older paintings, In the summer, they lived in the north of New York State in the Adirondacks, a region of forests and lakes that recalled the landscapes of their youth. Chagall felt ‘like a person in love following the moon’, as he wrote in 1943 to a friend. The next year they spent the summer at Cranberry Lake where the couple joyfully welcomed the news of Paris’s liberation, and began planning to return to France soon. But Bella fell ill a few days later, and died on 2 September. Chagall was devastated: he had lost ‘his kindred spirit, his seraphic angel, the very personification of beauty and love’. This portrait of the couple is a moving testimonial of their last summer together.

Shortly before she died, Bella had drafted this introduction to Burning Lights: 36 Drawings by Marc Chagall, eventually published in 1946. Her words seem to echo the nostalgia of the painting:

Far as my childhood years have receded from me, I now suddenly find them coming back to me, closer and closer to me, so near, they could be breathing into my mouth. I see myself so clearly a plump little thing, a tiny girl running all over the place, pushing my way from one door through another, hiding like a curled-up little worm with my feet up on our broad window sills.

My father, my mother, the two grandmothers, my handsome grandfather, my own and outside families, the comfortable and the needy, weddings and funerals, our streets and gardens all this streams before my eyes like the deep waters of our Dvina.

My old home is not there any more. Everything is gone, even dead. … The children are scattered In this world and the other, some here, some there. But each of them, in place of his vanished inheritance, has taken with him, like a piece of his father’s shroud, the breath of the parental home.

I am unfolding my piece of heritage, and at once there rise to my nose the odours of my old home. My ears begin to sound with the clamour of the shop and the melodies that the rabbi sang on holidays. From every corner a shadow thrusts out, and no sooner do I touch it than it pulls me Into a dancing circle with other shadows. They jostle one another, prod me in the back, grasp me by the hands, the feet, until all of them together fall upon me like a host of humming flies on a hot day. I do not know where to take refuge from them.

And so, just once, I want very much to wrest from the darkness a day, an hour, a moment belonging to my vanished home. But how does one bring back to life such a moment? Dear God, it is so hard to draw out a fragment of bygone life from fleshless memories! And what if they should flicker out, my lean memories, and die away together with me? I want to rescue them.

In 1948, Chagall returned from America, and in 1950 bought a house in Vence, just north of Nice. Here, he began to branch out technically, creating a large ceramic murals and his first stained-glass windows. Over the next 20 years, the artist fulfilled many important public and private commissions: stained-glass windows (for example in Jerusalem, the UN HQ in New York), paintings (the ceiling of the Opéra National de Paris, murals in the New York Metropolitan Opera), mosaics (The Four Seasons, 1974, Chicago) and tapestries (Gobelins tapestries designed for the Knesset).

There’s a Gobelin tapestry on display here: Mediterranean Landscape, woven in 1971 and reflecting his joy in the landscape of the Cote d’Azur, the place where in Chagall’s own words, he was ‘born for the second time’. The sky is inhabited by characters dreamed by the poet sitting under the tree on the far right – birds, a fish, flowers, an embracing couple carried aloft on the back of a flying horse. There are two suns in this sky – each above the towers of a town – the one on the left suggests St. Paul de Vence where Chagall settled in 1966 and stayed for the rest of his life. On the right the palm trees along a sea front suggest Nice, the Promenade and the hills covered with buildings.

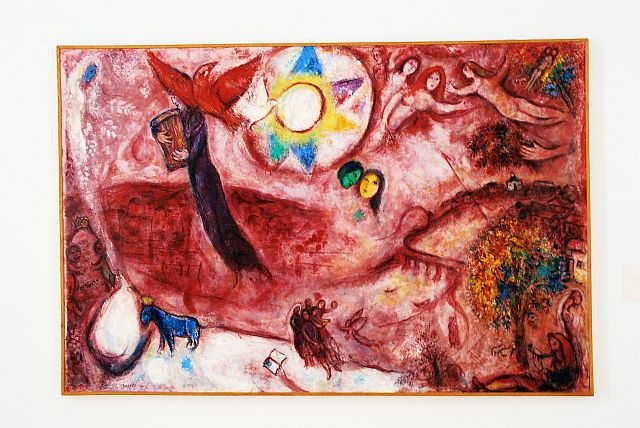

In 1964 Chagall summed up his entire life in a single painting that concludes this special exhibition. La Vie is an enormous canvas painted for the opening of the Maeght Gallery in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. All of the main aspects of his life and art can be seen in this composition: his Jewish roots, his love for the people in his life, dreams, nature, creativity and music. His love of creativity is evident in the fact that many of the images are of performers.

A key theme theme in La Vie is music, represented by the violin which Chagall learned in Russia at a young age. Violins would also be played in his home town to mark major turning points in life such as birth, death and marriage. Many works have included acrobats, and this piece features acrobats and musicians as if performing in a circus.

In our life there is a single colour, as on an artist’s palette, which provides the meaning of life and art. It is the colour of love.

– Marc Chagall

From here, we moved on to the permanent display which is dominated by a cycle of seventeen vast paintings cycle which goes under the title, The Biblical Message. The paintings are arranged in two groups: the first twelve depict episodes from Genesis and Exodus, while the other five paintings illustrate the Song of Songs as variations on the theme of love.

Chagall donated the paintings that comprise The Biblical Message to the French State in 1966. Deeply shaken by the massacre of the Jews and destruction of Yiddish culture in the Holocaust, in the postwar period Chagall gave his art a much stronger religious focus, taking the subjects for his paintings directly from the Bible. After the cycle had been exhibited in the Louvre, the Minister of Culture, Andre Malraux, moved quickly to organise a place where the paintings could be displayed permanently.

The Chagall Museum in Nice was inaugurated in 1973 in Chagall’s presence; the painter made a speech in which he explained the thinking that underlay the cycle, and his hopes for the Museum which included these words:

To my thinking, these pictures do not represent the dream of a single people but of all humanity. Are not painting and colour inspired by Love? ls not painting only the reflection of our inner self, and so is not mastery of the brush surpassed? … If all life moves inevitably towards its end, then we must, during our own, colour it with our colours of love and hope. In this love lies the social logic of life and the essential part of each religion. […]

Perhaps the young and the less young will come to this House to seek an ideal of fraternity and love such as it has been dreamed by my colours and my lines. Perhaps, too, they will speak the words of the love that I feel for all. Perhaps there will be no more enemies and, as a mother brings a child into the world with love and pain, so the young and the less young will build the world of love with a new colour. And all, whatever their religion, will be able to come here and talk about this dream, far from wickedness and agitation. I would like works of art and documents embodying the elevated spirituality of all peoples to be exhibited here, for their music and poetry that come from the heart to be heard here.

ls this dream possible? In Art as in life, everything is possible if, deep down, there is Love.

What Chagall seems to be saying is that you don’t need to be the follower of a particular religion – or indeed any religion – to experience something deeply spiritual and uplifting in this place. The impact of the paintings is enhanced by the beautiful simplicity of the building’s harmonious design. The rooms are light, white, and cool, with large, shaded windows that admit a delicate light.

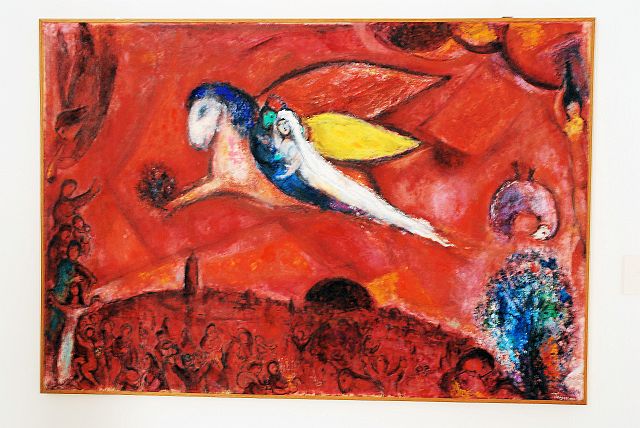

The hexagonal room that houses the Song of Songs cycle is undoubtedly the highlight of any visit to this remarkable building. Chagall himself chose the placement of works in this room, with each of the five canvases that form the cycle displayed in succession on five of the walls, leading the gaze from one painting to the next.

Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth:

for thy love is better than wine. (1.2)

Chagall does not illustrate the text in precise detail, but vividly conveys the three dimensions of the Song of Songs: the musical, the sacred and the sensual.

A bundle of myrrh is my well-beloved unto me;

he shall lie all night betwixt my breasts. (1.13)

Shades of red and pink suffuse the paintings and the room, evoking the softness of the flesh and sensuality, but also blood and the violence of the Biblical narrative in which David, in order to make Bathsheba his own, sends her husband to war so that he will be killed.

Until the day break, and the shadows flee away,

I will get me to the mountain of myrrh,

and to the hill of frankincense. (4.6)

The third canvas could almost be the story of Chagall’s own life. Replacing the image of Jerusalem in the second panel are two towns that mirror each other: Vence, recognised by the tower of its cathedral, and below Vitebsk, the painter’s birthplace identifiable from the synagogue with its green dome.

I sleep, but my heart waketh:

it is the voice of my beloved that knocketh, saying,

Open to me, my sister, my love, my dove, my undefiled:

for my head is filled with dew,

and my locks with the drops of the night. (5.2)

The fourth panel is the one most often reproduced for posters and postcards. Here the couple are shown on the back of a winged horse riding over Jerusalem. In Chagall’s multi-layered meanings, the horse represents desire and physical love, but also Pegasus, the winged horse of Greek myth that symbolises poetry, and may in addition embody the power of human love. The bride’s gown tapers away like a comet, heightening the sense of movement. David’s face is ‘green with happiness’ – apparently a Yiddish expression. In the crowd below people carry the Torah and menorahs. The painting seems to celebrate the love of men and women and, simultaneously, the love of the believer for their god.

How beautiful are thy feet with shoes, O prince’s daughter!

the joints of thy thighs are like jewels,

the work of the hands of a cunning workman. (7.2)

Alongside each painting is a short excerpt from the Song of Songs in French – I have included these in translation here. At the entrance to the room is this short dedication from Marc Chagall to his wife: my gladness and joy.

On the other side of the Song of Songs room is the Mosaic room where your eyes are drawn to a picture window with, beyond, a pool and fountain, and on the far side a large mosaic that depicts the prophet Elijah in his chariot of fire.

It’s important not to miss the music room which Chagall insisted the building should contain. It features remarkable stained glass windows, designed by Chagall, that depict the creation of the world. In the first window is Chagall’s interpretation of the first four days when God created the universe: light separating from darkness, the elements and the planets coming into being. The next window shows the creation of plants, animals and Adam and Eve. The last and most narrow window depicts the seventh day, with angels singing their praises of God.

Chagall continued to work right up until his death on 28 March 1985 in St. Paul de Vence, where he is buried.

Thank you Gerry. That’s so good and lovely of you to post many thanks Its beautiful and interesting. Great

Sarah

WONDERFUL

WONDER IF THERE IS A BOOK ON THE MUSEUM

Thanks, Maurice. There’s a catalogue, available on Amazon: http://amzn.to/2wgSViz

lovely post