There is no frigate like a book

To take us lands away,

Nor any coursers like a page

Of prancing poetry.

This traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of toll;

How frugal is the chariot

That bears a human soul!

– Emily Dickinson

As we blog do we sense over our shoulders, the line of writers who have preceded us, stretching 3000 years into the past? Because that’s how long we humans have been at it, a continuous arc of expression surveyed in Melvyn Bragg’s week-long In Our Time special, The Written World. The series investigated how writing and the technologies for recording it have shaped intellectual history.

This is the sort of thing that Melvyn Bragg does wonderfully well – the programmes were absorbing and entertaining, informing without simplifying. Bragg’s thesis was that writing was the greatest human invention, and the focus was on artefacts (all from museums in Britain), the technology for recording words: tablets, manuscripts and books, each of which in some way represented a turning point in the history of ideas.

In the first programme, Bragg focussed on how the technology of writing evolved from making signs on clay or wood to writing on parchment – and how these advances enabled the development of human culture. In the British Library he examined examples of cuneiform tablets from southern Mesopotamia dating back to 3400 BC, first produced when writing emerged as a form of accountancy.

In the second instalment, Bragg traced the evolution of writing technology from the time of classical antiquity to the invention of printing. In the British Library he meets the Lead Curator of Medieval and Earlier Manuscripts, Claire Breay, who opens a small wooden box. It contains an object so precious that it’s kept in a strongroom, and only one person – Claire – is allowed to handle it. As Bragg watches, she slides off the lid to reveal a small linen-wrapped package. This is the St Cuthbert Gospel, the oldest surviving European book, produced in Northumbria in the 7th century; it owes its immaculate condition to the fact that it spent the first four hundred years of its existence in the saint’s coffin.

These early books were bound copies of handwritten manuscripts, each copy the result of laborious and painstaking work by scribes (usually monks) who each worked on one section of the text. In Europe it wasn’t until the mid-16th century that Johann Gutenberg invented a mechanical way of making books. Melvyn Bragg looked at copies of the Gutenberg Bible – the version printed on paper in the British Library, and a copy printed on vellum held by the British Museum.

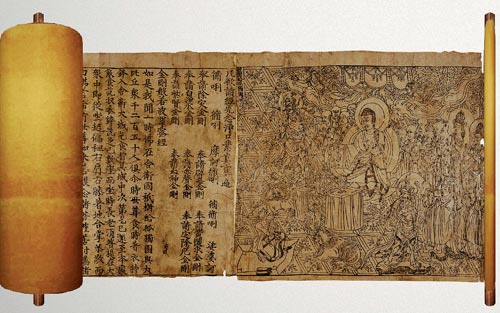

But this isn’t the world’s oldest printed book: that is not European but Chinese, and it was produced in 868. A copy of the Diamond Sūtra, a key text in Buddhist teaching, is, in the words of the British Library, ‘the earliest complete survival of a dated printed book’.

Melvyn Bragg focussed on how the invention of writing influenced the spread of religion in the third programme of the series, looking at how the evolution of writing materials and techniques allowed religions to develop, and examining some of the earliest surviving sacred texts, including the 4th-century Codex Sinaiticus and a Koran produced in Iraq in the 8th century. In the library of Durham Cathedral, he was shown a medieval Gospel that is the oldest illuminated manuscript in the Western world.

In the next episode, Melvyn Bragg investigated how the written word, a technology originally employed for keeping accounts, gave rise to literature in all its forms. He charted the emergence of poetry and history writing in the ancient world, and discovered how Greek literary traditions reached this country in the Middle Ages. A highlight was his encounter with the only known manuscript of Beowulf, dating from around 1000, which is now housed at the British Library. Beowulf is the longest epic poem in Old English, the language spoken in England before the Norman Conquest.

Bragg concluded his survey of the written word by considering how the invention of writing made the scientific revolution of the Enlightenment possible. He examined influential documents, including the notebooks of Sir Isaac Newton held at the University of Cambridge and meticulous astronomical and meteorological observations recorded on large sheets of paper by Captain James Cook during his third exploratory voyage in the Pacific in 1779 – also held in Cambridge University Library.

All told, the five 30-minute programmes provided an engrossing survey of the evolution and significance of the written word and the technology for disseminating it. But with the future of the book (and of libraries) being hotly debated at present, I felt the need for at least one more episode that explored the issues surrounding the development of electronic media – both for writing (web pages, email, blogging, tweets, etc) and for reading (iPad and Kindle).

Washington blogger Mike Licht has made a humourous comment on the present juncture with this manipulated image – ‘Mrs Duffee Seated on a Striped Sofa, Reading Her Kindle, After Mary Cassatt’. To see the original go here.

This reminded me that many artists – from Rembrandt to Picasso have painted people reading (and also, to a lesser extent, writing), usually in order to capture the thoughtful expression on the subject’s face of someone deeply absorbed by a book or letter.

Vermeer’s ‘Woman In Blue Reading a Letter’ is mirrored by his ‘ Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid’.

Another superb Renaissance portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger chooses as its subject the theologian and early proponent of religious toleration, Erasmus of Rotterdam in the act of writing.

Matthias Stom was a painter of the Dutch golden age. His ‘Young Man Reading By Candlelight’, painted sometime in the first half of the 17th century, gives a powerful sense of what the experience of reading after dark would have felt like at the time.

In the sixteenth century artists generally pictured people reading holy scriptures, but their focus gradually shifted to more secular concerns – Vermeer’s women reading private letters, for example. The advent of the novel and their popularity drew artists from the 19th century onwards towards representing the inwardness and absorption particularly associated with the private act of novel reading. John Singer Sargent’s ‘Man Reading’ and Edgar Degas’ ‘Portrait of Edmond Duranty’ are both examples of this tendency, with Degas’ man portrayed as a reader and a thinker, and probably about to put pen to paper.

And let’s not forget photographers, either. They, too, have been fascinated by people reading. The image at the head of this post is of a scene in Burma by the American photographer Steve McCurry, one of many images of readers from around the world that he has made. Just the other day, the death was announced of the great photojournalist Eve Arnold. Arnold spent most of her career as a member of Magnum, and travelled to places such as Mongolia, China and Dubai, capturing stunning images of ordinary life. She produced many photo essays on diverse subjects, such as factory workers and harem women, and one in the early 1960s about Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam. In 1955, she joined other Magnum photographers at the filming of The Misfits, where she captured this iconic image of Marilyn Monroe reading James Joyce.

I haven’t been able to find out much about Gustav Adolph Hennig, other than he was a German artist of the 19th century, but his portrait of a girl reading is certainly striking.

Moving into the 20th century, the French painter Yves Trevedy, produced this characterful portrait of an old man concentrating deeply on the words on the page, while Edward Hopper caught the act of reading on public transport.

Another photographer, Andre Kertesz, had a lifelong photographic project: to capture people reading, in all situations, but usually outdoors on the street – eventually gathered in book form as On Reading. Blake Morrison once wrote of Kertesz that:

[He] didn’t live to see the age of the internet or to hear the funeral rites for the age of print. But his photos of readers aren’t just a historical document or an exercise in nostalgia. The essential image he works with is timeless: human interaction with the written word. The physical forms in which we receive the word may be changing. But even when ebooks and Blackberries have taken over, that central image will remain: a text held in the hand and a head bowed over it.

Download link no longer works for Written Word – this one should: http://www.badongo.com/file/26164695

Great images of readers here – I do like the Steve McCurry images so thanks for the link to that.

Cheers, Diana. Funny that this post from a year ago should echo your most recent one! (http://dianajhale.wordpress.com/2013/01/13/words-found-in-the-landscape/)

I think that must be why I suddenly spotted it!

A wonderful post. Odd, but I’d just posted that shot of Marilyn on Facebook minutes before seeing this post.

Thanks for that, Bill. Coincidences, eh?

I guess I was meant to read your post.