What a dispiriting programme this was, the second in the British Masters series presented by James Fox. It offered a survey of British art in the inter-war years, an interesting period in British art when artists were facing up to challenging continental currents in artistic expression, and responding to the aftermath of the War, growing social distress and intensified class conflict.

But, as in last week’s episode, Fox dealt in elision and hyperbole, determined to shoehorn glimpses of artists and their work into his argument that British artists collectively came to define what it meant to be British – to such a degree, he implied, that they helped Britain win the Second World War:

It was their paintings together that gave us a vision of the England that we were fighting for. In an age of anxiety, artists helped Britain find itself again. In their paintings they remembered a country to which we could escape; they invented a country that all of us could love. And in the shadow of a new war, they forged a country for which all of us could fight.

While it is true that an argument can be made that artists such as John Nash, Graham Sutherland, Eric Ravilious and others helped define an image of England in the public mind, this largely came about as a result of a phenomenon not mentioned by Fox – the outstanding and iconic images produced for Shell and London Transport posters by these artists and others during the 1930s. Here is a selection:

Graham Sutherland

A Staurt-Hill

Paul Nash

Vanessa Bell

Edward McKnight Kauffer

Eric Ravilious produced a series of acclaimed woodcuts for London Transport, and although Train Landscape (above) was not used as a poster, it might have been.

The image chosen to open and close the episode – The Cornfield by John Nash (top) was painted as a response to war, though not, as Fox implied, the Second World War. John Nash and his brother Paul had served at the Western Front in the Great War. On their return to England, they rented a studio in Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire, where John painted The Cornfield, a poignant contrast to the brothers’ paintings of devastation and death at the front they were working on as commissions at the same time. John later said that they used to paint for their own pleasure only after six o’clock, when their work as war artists was over for the day. This explains the long shadows cast by the evening sun across the golden field of corn that is the focus of the painting. John Burnside’s wrote a beautiful meditation on The Cornfield for the Tate blog:

Nothing is as it was

in childhood, when we had to learn the names

of objects and colours,

and yet the eye can navigate a field,

loving the way a random stook of corn

is orphaned

– not by shadows; not by light –

but softly, like the tinder in a children’s

story-book, the stalled world raised to life

around a spark: that tenderness in presence,

pale as the flame a sniper waits to catch

across the yards of razor-wire and ditching;

thin as the light that falls from chapel doors,

so everything, it seems,

is resurrected;

not for a moment, not in the sway of the now,

but always,

as the evening we can see

is all the others, all of history:

the man climbing up from the tomb

in a mantle of sulphur,

the struck match whiting his hands

in a blister of light.

In the last four stanzas it’s as if Burnside has moved on to contemplate another painting discussed by Fox in the programme – Stanley Spencer’s Resurrection, Cookham (below).

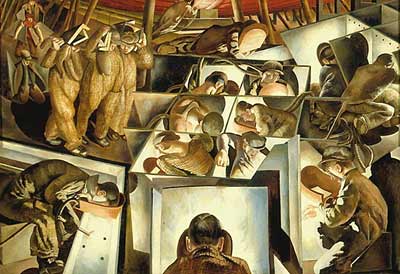

After the usual tour of Cookham and the details of Resurrection, Fox quickly moved on to consider Spencer’s sex life, spending some time poring over Double Nude Portrait- The Artist with His Second Wife and what it tells us about his two marriages. Fascinating, perhaps, but more pertinent to Fox’s thesis about artists contributing to a sense of national unity during wartime would have been the eight panels he painted while working as a war artist at Lithgows Shipyard in Port Glasgow, on the Clyde in 1940.

These works seem much more relevant to the question of how British people saw themselves in relation to the war effort. Spencer depicts an egalitarian working environment, one operating through co-operation and co-ordination. There are no foremen. It’s a vision of a new social order and a challenge to the existing order, and articulates a mood that emerged during the war and was expressed ultimately in the Labour landslide in the 1945 election.

Perhaps Spencer’s complicated sex life was the sort of thing that Fox was referring to in his blog on the BBC website when he wrote in advance of the series, ‘I promise you that there will be some jaw-dropping stories’. Or perhaps it was the story of the obnoxious president of the Royal Academy and painter of endless horse portraits, Sir Alfred Munnings, getting pissed before making a speech in the presence of Winston Churchill in which he savaged modernists. But Dr Fox loves Munnings – he, too, helped define true Englishness.

The final work that Fox considered was John Piper’s Interior, Coventry Cathedral (below), painted in the immediate aftermath of the German bombing raid on the city on 14 November 1940. For the 12 hours German bombers laid waste to the city below, destroying thousands of buildings and killing hundreds of civilians. Early the following morning, Piper, an official war artist, painted the aftermath of the attack.

James Fox said of the painting:

It shows the city’s great medieval cathedral in ruins. The roof has collapsed, the windows are smashed, and the rubble is still smouldering. It was a metaphor for the entire British nation as it teetered on the brink of annihilation. In the darkest hour of World War 2, the public actually saw it as an image of defiance. Because in the face of all that terrible destruction, those old English walls are standing firm. And if a building won’t give up, neither will the people.

The story is a good one, and the contextualisation was appropriate. But surely, in a series about art, there should be more of a focus on the art itself? What makes this a great piece of art – apart from the circumstances of its creation? How does it relate to Piper’s other work and his artistic strategies? This is not a new complaint about art documentaries on TV, and the response is usually along the lines of: to attract and hold an audience it’s necessary to focus on drama and personalities, rather than abstractions. And there isn’t time to go into all the twists and turns of art movements.

But how long would it take to outline the role that artists like Paul Nash or John Piper played at this time in creating something new – a blend of abstraction and an older tradition of landscape painting to produce an approach that was distinctively British? Surely that is an interesting story – not the fanciful idea that they helped win the Second World War?

It’s a story that Alexandra Harris tells in her prize-winning book Romantic Moderns. She writes that ‘Piper is so well-known today for his romantic vision of churches and country houses that it can be difficult to imagine him as a leader of the abstract movement’. In Breakwaters at Seaford (1937, below), jetties and waves are inked ‘with calligraphic sketchiness’ and paper is torn and ripped, leaving raw edges exposed, to evoke a sense of winter wind and waves.

A painting like this that is part-collage reveals the influence on Piper of the Cubist practice (Braque, for instance) of pasting pieces of paper, newsprint and so on into a painting. This can be seen clearly in Beach with Starfish (below).

But, says Harris, ‘whereas Braque and Picasso made their collages indoors, arranging wallpapers and veneers with infinite deliberation to signify tables, bottles, and guitars, Piper sat outside with a board on his knees, opening his work to nature and to chance’.

Piper crystallised his ideas in an essay, ‘Abstraction on the Beach’, in which he argued that ‘abstraction is a luxury’ – and as old as the hills. He wrote that,

The early Christian sculptors, wall-painters and glass-painters had a sensible attitude towards abstraction. However hard one tries … one cannot catch them out indulging in pure abstraction. Their abstraction, such as it is, is always subservient to an end – the Christian end, as it happened. Abstraction is a luxury that has been left to the present day to exploit It is a luxury just as any single ideal is, and like a single ideal it should be approached all the time, but not pre-supposed all the time. To pre-suppose it always, if you are a painter is to paint the same picture always: or else to give up painting altogether because there is nothing left to paint….

Piper was determined to renew the connection between art and life, that would look for the sacred in ordinary, local things.On the beach, for example:

At the edge of the sea, sand. Then, unwashed by the waves at low tide, grey-blue shingle against the warm brown sand: an intense contradiction in colour, in the same tone, on the same plane. Fringing this, dark seaweed, an irregular litter of it, with a jagged edge towards the sea broken here and there by washed-up objects; boxes, tins, waterlogged sand shoes, banana skins, starfish, cuttlefish, dead seagulls, sides of boxes with THIS SIDE UP on them, fragments of sea-chewed linoleum with a washed-out pattern. This line of magnificent wreckage vanishes out of sight in the distance, but it is a continous line that girdles England, and can be seen reappearing on the skyline in the other direction along this flat beach. Behind this rich and constricting belt against the sand dunes there is drier sand, sparser shingle, unwashed even at high tides, with dirty banana skins now and sides of boxes with the THIS SIDE UP almost unreadable. That, in whatever direction you look, is a subject worthy of contemporary painting. Pure abstraction is undernourished. It should at least be allowed to feed bare on a beach with tins and broken bottles.

This tension between nationalism and internationalism, between abstraction and the English landscape tradition, in British art of the period makes for an interesting story, and challenging questions. Has British art been at its best when drawing on influences from abroad? Or when it draws strength from native customs and traditions?

Paul Nash was a pioneer of modernism in Britain, promoting the avant-garde European styles of abstraction and Surrealism in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1933 he co-founded the influential modern art movement Unit One with fellow artists Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth (no mention of them by Fox), and the critic Herbert Read. It was a short-lived but important move towards the revitalisation of English art in the inter-war period. But then, in Axis, England’s most adventurous art magazine at the time, Paul Nash expressed his desire to be a modernist while still working in a native tradition:

Whether it is possible to ‘go modern’ and still ‘be British’ is a question vexing quite a few people today […] The battle lines have been drawn up: internationalism versus an indigenous culture; renovation versus conservatism; the industrial versus the pastoral; the functional versus the futile.

He explained why he was ‘For, but Not With’ the abstract painters, able to appreciate abstraction, but ultimately more satisfied by nature: by stones and leaves, trees and waves. Nash wanted to create a national identity for modern art, and began by exploring the coastline of Dorset, its cliffs studded with fossils, and the chalk downland marked by paths like mysterious engravings on the land.

Nash was a member of the English Surrealist movement, and his greatest paintings were symbolic representations of specific landscapes – the Dorset coast (above), the ancient stone circle at Avebury in Wiltshire, and of other ancient sites in England including Wittemham Clumps (below). The Clumps – the two dome-shaped hills topped by a thick clump of trees – had been familiar to Nash since spending family holidays nearby from 1909. He painted the Clumps in a series of dream-like works, three of which present the vernal (or spring) equinox, with the sun and moon depicted simultaneously in the sky.

Like Piper, Nash wanted to reconcile modernity with Britishness. Having tried abstraction, he returned to painting of natural forms – stones, leaves and trees. Although he greatly admired (and in many cases rubbed shoulders with) Picasso, Max Ernst, Magritte and other modernists, he continued to find inspiration in nature and the British landscape. He saw himself in the tradition of English mystical painters such as William Blake and Samuel Palmer.

The 1935 painting Equivalents for the Megaliths (above) shows Nash working in both traditions – juxtaposing avant-garde with the mystical spirit of a place in the English landscape. Near the horizon a hill-fort or barrow is visible, while dominating the foreground are his equivalents for the megaliths, the Avebury standing stones. Assembled in a cornfield are the powerful geometric forms of a gridded screen, standing and lying cylinders, and a steel-grey girder. Alexandra Harris explains that equivalents was a word that Roger Fry ‘often used to explain the goal of non-representational art, arguing that instead of mimicking the world the picture must be allowed to make its own, equivalent, reality’.

Nash was not the only artist ‘worried that they might be heading for … abstract oblivion’. Another was Ivon Hitchens. For Hitchens, the landscape was important as ‘a peg on which to hang a painting’. In other words,he wanted to paint something more than the landscape in front of him. After his house was bombed in 1940, Hitchens moved to a patch of woodland near Petworth in Sussex, living at first in a caravan. Here, using just patches of colour and brush strokes, he created landscapes (below) with a sense of movement, depth and space.

Eric Ravilious followed a similar path, working to create a traditional, non-chauvinistic sort of Englishness, and became one of the best-known artists of the 1930s. Inspired by the landscape of the South Downs, his paintings featured, in his words, ‘lighthouses, rowing-boats, beds, beaches, greenhouses’. Some dismissed Ravilious’s art as cosy or parochial, but he was a masterful watercolourist whose paintings are never merely pretty. They reveal the same complicated relationship with modernism as the work of Nash or Sutherland. ‘I like definite shapes’, he wrote, and his landscapes approach the abstract with their flat planes and hard lines and patterns.

A far less well-known painter in the inter-war years was David Bomberg. He had studied at the Slade alongside Stanley Spencer and C.R.W. Nevinson and in his early work had been greatly influenced by cubism. But in the post-war years his work, too, became increasingly dominated by landscapes drawn from nature that combined abstract, expressionist forms with naturalism. During and shortly after the Second World War he spent time in Cornwall, where he painted Tregor and Tregoff (below).

In 1944 he painted Evening in the City of London, which, like Piper’s painting of the bombed-out Coventry Cathedral, seemed to express optimism through its strong blocks of warm colour. It has been described as the ‘most moving of all paintings of wartime Britain’. Bomberg once said: ‘I want to translate the life of a great city … into art that shall not be photographic, but expressive’. Andrew Graham Dixon writes:

Like many another wartime Londoner, Bomberg was struck by the seemingly miraculous way in which Christopher Wren’s great cathedral of St Paul’s had survived the incessant bombing attacks of the Nazis. He took care to show the cathedral from a distance, framed by the desolation around it. According to the artist’s wife, Lilian Bomberg, “He got permission to climb to the top of a church, in Cheapside, I think, and painted St Paul’s from its east side.” The church in question was probably St Bride’s. Access to public buildings deemed to be prime targets for enemy attack was severely restricted.

The tension between realism and abstraction can also be seen in the work of Henry Moore. In his sculpture he had moved steadily from classicism to abstraction and his work became a target for the popular press. When his abstract Mother and Child in stone was put on display in a front garden in Hampstead, the work proved controversial with local residents and the local press ran a campaign against the piece for two years.

Yet the Shelter Drawings, created by Moore after he was commissioned as an official war artist, transformed his reputation. Along with the coalmining drawings also produced during the war, they transformed miners and London’s working class sheltering in the Underground into heroic figures, stoic and quietly determined.

James Fox touched on the two traditions of painting and photography that mingled from the 1930s onwards. There was often collaboration between photographers and documentary film-makers – such as Humphrey Spender, Bill Brandt and John Grierson – and painters, including Stanley Spencer, and the example Fox chose, William Coldstream.

I didn’t find the Coldstream images especially interesting (Fox observed that his early work was ‘rather pedestrian’, but I love the photos that Spender took in 1937-38, when he went to Bolton on behalf of Mass Observation, the ‘fact-finding body’ set up by Humphrey Jennings and Tom Harrison to document the lives of ordinary British people. As Spender saw it, his role as photographer was to provide visual “information” to complement the written accounts. This is his famous ‘Washing Line’ shot:

James Fox mentioned how Bill Brandt was photographing the Sitwells at Renishaw Hall at the same time as John Piper was painting the great house. Brandt photographed people in all kinds of circumstances in the 1930s:

Finally, what about some art produced by people at the other end of the social scale to the likes of Piper, Spencer or Nash? The Ashington group consisted of Northumberland miners who first came together in 1934 through the Workers Education Association to study ‘something different’ – art appreciation. In an effort to understand what it was all about, their tutor Robert Lyon encouraged them to learn by doing it themselves.

The images that the group produced were fascinating and captured every aspect of life in and around their mining community – above and below ground, from scenes around the kitchen table and on their allotments, to the dangerous and dirty world of the coal face. Was this the England for which James Fox was searching?

Leslie Brownrigg – The Miner, c.1935

Harry Wilson – Committee Meeting, c.1937

George Blessed – Whippets

Fred Laidler – Fish and Chips

I am way out of my depth here since my knowledge of things art stopped the day World War One broke out in 1914. But I was very interested in the two 2011 exhibitions – 1] British Impressionism and 2] The Restless Times, Art in Britain 1914-4.

You have tackled a very tough time in world, European and British history, but you found some great paintings that stood the test of time, even after the really horrible years ended. Nash and Spencer are well known already, but I think Ravilious is getting there and Piper deserves to be better known.

Thanks for the link

Hels

http://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com/2012/01/two-exhibitions-of-british-landscapes.html