Last week was Refugee Week, though you wouldn’t have known it in a country now obsessed with borders and controls and frighteningly comfortable with demonising outsiders. I only learnt about it from the estimable Passing Time blog. The day after the appalling referendum result we sat down to watch Fire at Sea, Gianfranco Rosi’s strange but compelling documentary which observes the impact of the refugee crisis on the island of Lampedusa with a calm and unembroidered stare. Continue reading “Fire at Sea: life goes on while a human catastrophe unfolds at sea”

Tag: Italy

Watching migrants drown: ‘there are lines which, if crossed, make us immoral’

Martin Rowson in today’s Guardian

A few days ago I posted a piece about the photo of desperate migrants perched on top of the border fence that surrounds the Spanish enclave of Melilla on the north African coast. Now we learn that the British government has supported, and the EU justice and home affairs council has adopted a policy of leaving migrants to drown.

For the past year the Italian navy, with EU financial and logistical support, has operated a search-and-rescue operation called Mare Nostrum for migrants in danger of drowning in the Mediterranean which has saved the lives of an estimated 150,000 refugees. It is to be replaced with a much more limited EU ‘border protection’ operation codenamed Triton which will not conduct search-and-rescue missions. The justification given by both the UK government and the EU for this inhumane decision is that Mare Nostrum exercised a ‘pulling factor’, encouraging economic migrants to set sail for Europe.

Amnesty International’s UK director, Kate Allen, said today that history would judge the decision as unforgivable:

This is a very dark day for the moral standing of the UK. When the hour came, the UK turned its back on despairing people and left them to drown. The vague prospect of rescue has never been the incentive. War, poverty and persecution are what make desperate people take terrible risks.

Migrants are impelled by a potent combination of desperation and aspiration, global inequalities in work and freedom, and the insecurity created by war and persecution across north Africa and the Middle East. The poor and oppressed will always move in search of work and freedom in a world so unequal.

Refugee boat off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa

This morning’s Guardian editorial pulls no punches:

The British government’s refusal to support search and rescue missions to save refugees in the Mediterranean is an outrageous and immoral act. It suggests a government so alarmed by Ukip that it has lost all sense of proportion. The Italian-funded Mare Nostrum exercise, mobilised after 300 refugees drowned off Lampedusa a year ago, has saved thousands of lives. […] What a grotesque betrayal of the founding principles of the EU, an organisation built on the promise of peace, prosperity and asylum for the desperate. What an indictment of timid politicians.

On the letters page, the artist Anish Kapoor asks, ‘Have we lost our sense of common humanity? Are we to isolate ourselves to such an extent that we are unable or unwilling to reach out to our fellow human beings? These people find themselves in such dire difficulties that they see no choice but to take to the high seas and risk their lives in vessels that are woefully inadequate. Let us not forget that our government acts in our name and that each of us is implicated in this act of barbaric selfishness.’

Yesterday Nicholas Winton, the British man who saved 669 Jewish children from the Nazi concentration camps by arranging trains to take the children out of occupied Czechoslovakia to be fostered in Britain, was awarded the Czech Republic’s highest state honour. How does the morality of the decision to end support for Mare Nostrum differ from that of European countries that turned their backs on the Jews in 1939? That was the year when WH Auden wrote ‘Refugee Blues’, from which I’ve taken these extracts:

Some are living in mansions, some are living in holes:

Yet there’s no place for us, my dear, yet there’s no place for us.

Once we had a country and we thought it fair,

Look in the atlas and you’ll find it there:

We cannot go there now, my dear, we cannot go there now.

[…]

The counsul banged the table and said,

‘If you’ve got no passport you’re officially dead’:

But we are still alive, my dear, but we are still alive.

[…]

Walked through a wood, saw the birds in the trees;

They had no politicians and sang at their ease:

They weren’t the human race, my dear, they weren’t the human race.

Dreamed I saw a building with a thousand floors,

A thousand windows and a thousand doors;

Not one of them was ours, my dear, not one of them was ours.

As Alex Andreou observes in ‘Random acts of kindness can make the world a better place‘ this is all about ‘lack of kindness and meanness of spirit’. He continues:

There are lines which, if crossed, make us immoral as a country. This is one of them, especially considering our involvement in the conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa which fuel the surge in refugees. It leaves our allies with a choice to either make up the shortfall or let people drown in their waters. People – men, women and children – not migrants or refugees; not numbers. Families like mine and yours, fleeing in precisely the same way we would if we lived in a war zone.

We bewail the loss of our values, whether we call them civilised, British, western or Christian. We turn to a minority of migrants and blame them for ostensibly diluting them. But it is simply not true. The reason we are losing our values is that we are failing to nourish them, cherish them and hold on to them. It is a collective meanness of spirit.

The reason we are becoming less and less like the Britain we recognise is not the presence of Polish plumbers; it is the putting up of spikes to shoo away the homeless instead of offering them a cup of tea. The reason this is no longer a civilised country is not the presence of a smattering of mosques; it is the decision to let people drown in the sea to save a measly amount which will not make even the smallest dent in our budget. The reason we are turning uncivilised, un-British, unchristian, un-western – however you define it – is the lack of tangible kindness. We are simply turning into the worst version of ourselves.

Rocella near Riace abandoned sailing ship Kurds ashore 1999

In December last year I wrote about Riace, a poor village in Calabria that has welcomed migrants with open arms. For more than a decade, since two hundred Kurds scrambled ashore from their sinking boat on the nearby coas,t the villagers have opened their doors to migrants in a dramatic reversal of usual attitudes towards immigrants. The left-wing mayor encouraged the Kurds to settle in his village replacing the people who had left and reversing his village’s decline. Since then, more ‘people who come from the sea’, as locals put it, have been encouraged to settle in the village.

Yesterday on the Today programme an Eritrean migrant,Daniel Habtey, who is now a British citizen, described his ‘horrendous’ journey to Italy on a tiny boat. He fled Eritrea with his wife and family ten years ago because the regime persecuted Christians and now lives and works as a Pastor in Huddersfield.

The dead from the Lampedusa tragedy

It’s barely a year since more than 300 African migrants drowned when their boat caught fire and sank off the Italian island of Lampedusa. Delalorm Sesi Semabia responded to the disaster by writing this poem:

We have laughed before

On the morning when we were born.

I was not there but they told me I laughed.

With careless glee, taking all the world in my gums.

And these ones

I heard them laugh

That early morning when the midwife brought them here

Telling tales of shot mamas and arrested papas

Certainly never to return.

I did not see them but I heard them laugh

Laugh at the world, laugh at all our world

Which would not laugh back.

Why do you ask us to laugh now

Here, at the brink of this water

Coming and going, calling us?

Why do you ask us to laugh

With a burnt village behind us

And drowned brothers before us,

On our way to Lampedusa?

What is humorous about paddling over the place

Where your brother’s carcass lies

Grinning up above at you

On your way to freedom,

And Lampedusa, death.

Wherein is the humour of overtaking your brother?

We sail away, our heads full of dreams

Dreams that come to us only by daylight

For where we stand,

We cannot sleep at night

And try as we do,

We have forgotten how to laugh.

A tale of two villages: it could be a wonderful life

The path to utopia

Politicians and media whipping up anti-immigrant hysteria. Savage welfare cuts while the super-rich live high on the hog. Deepening inequality and zero-hours contracts. Rapacious banks and untamed corporations. Corporate greed gouging the common weal. In these austere times, like George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life, one can easily become discouraged. The joyous cacophony of community life in Bedford Falls can seem like a distant dream of the silver screen.

But wait: here’s a tale of two villages. Real places, inhabited by real people who have taken a stand against profit and materialism, racism and fear. Two villages.

One….

Spain has been one of the countries hit hardest by the banking crash. At around 26%, Spain’s unemployment rate is the highest in the EU (and youth unemployment is nearly double that figure). In the wake of Spain’s property crash, hundreds of thousands of homes have been repossessed and half a million families have been evicted since 2008.

But, in Marinaleda, in impoverished Andalusia, the story is different. Unemployment is zero, with most of the villagers working for collectively-owned enterprises (growing food, building houses, working in shops, and running sporting, leisure and other basic services). Everyone works a 35-hour work week and earns a monthly salary of €1,128, at a time when the minimum wage in Spain is €641 per month. Many villagers rent a house of 90 square metres with a terrace for only €15 per month – a house that they have helped construct. Much of the land on which food crops are grown and houses are built is collectivised – once an estate owned by the aristocratic Alba family and awarded to the village by the regional government after a decade of occupations, strikes and appeals.

Sanchez Gordillo, Mayor of Marinaleda

For three decades Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo has been Marinaleda’s mayor, after winning the mayoral election in April 1979 as a representative of the United Workers’ Collective, a communist farm workers’ organization that promotes government through popular assemblies and believes that Andalusia should be independent from Spain. ‘I have never belonged to the communist party of the hammer and sickle, but I am a communist or communitarian’, Sánchez Gordillo has said, adding that his political beliefs were drawn from those of Jesus Christ, Gandhi, Marx, Lenin and Che. In 2013, he drew international media attention when he and a group of the villagers entered a supermarket and seized food, which they distributed to the area’s food banks – an action justified by Sánchez Gordillo with these words:

We’re doing something new here: we’re insisting that natural resources should be at the service of people, that they have a natural right to the land, and that land is not something to be marketed. Food should not be speculated with either. It is a basic human right.

Workers at the farming cooperative in Marinaleda

Marinaleda is a village which has known terrible hardship in the past. But today the villagers grow beans, artichokes, peppers and produce high-quality olive oil. The workers themselves control each phase of the production while the land belongs to the community as a whole. There is a collectively-owned cannery, olive mill, facilities for livestock and a farm store. Gordillo says:

We have learned that it is not enough to define utopia, nor is it enough to fight against the reactionary forces. One must build it here and now, brick by brick, patiently but steadily, until we can make the old dreams a reality: that there will be bread for all, freedom among citizens, and culture; and to be able to read with respect the word ‘peace ‘. We sincerely believe that there is no future that is not built in the present.

The village coat of arms: ‘utopia to peace’

Marinaleda, with some financial support from the Andalusian regional government, has been able to offer three things that much of Spain is desperately wanting: employment, affordable housing, and a more participatory democracy. ‘The most important thing we’ve done here is to struggle and obtain land through peaceful means, and to ensure that housing is a right, not a business, says Sánchez Gordillo. ‘And as a village we work together, discuss and collaborate together: that’s fundamental for any society, too.’

Utopia lies at the horizon.

When I draw nearer by two steps,

it retreats two steps.

If I proceed ten steps forward, it

swiftly slips ten steps ahead.

No matter how far I go, I can never reach it.

What, then, is the purpose of utopia?

It is to cause us to advance.

― Eduardo Galeano

The abandoned ship from which two hundred Kurds scrambled ashore in 1999 near Riace

Two…..

In another desperately poor part of Europe there is a village that has welcomed migrants with open arms. Riace lies on a hill five miles inland from the coast of Calabria in the far south of Italy. Little more than two months ago, more than 300 African migrants drowned when their boat caught fire and sank off the Italian island of Lampedusa. The tragedy resulted in many expressions of horror – from Italian politicians, the European Commission and the UN secretary general. Pope Francis was appalled: ‘The word disgrace comes to mind. It is a disgrace. Let’s unite our efforts so that tragedies like this don’t happen again. Only a decisive collaboration of everyone can help and prevent them’.

Riace

In Riace, for more than a decade, the villagers have collaborated in opening their doors to migrants in a dramatic reversal of usual attitudes towards immigrants. Calabria is a poor part of Italy, where villages are dying as young people leave in search of work in the cities of the north. So, after two hundred Kurds scrambled ashore in 1999 from their sinking boat on the coast near Riace, Domenico Lucano – another left-wing mayor – encouraged the Kurds to settle in his village replacing the people who had left and reversing his village’s decline. Since then, more ‘people who come from the sea’, as locals put it, have been encouraged to settle in the village.

Riace’s eco-traditional refuse collection

Instead of watching the sea-borne migrants get packed off to one of Italy’s grim immigrant holding centres, Lucano offered them houses in the village that had been abandoned as the local population dwindled. After all, he said, ‘My parents always taught me to welcome strangers’.

In the last few years, following the Riace model, five small villages, have joined to offer immigrants arriving from across the sea a warm welcome along with homes in empty buildings. In Riace this October, the Guardian reporter found two men leading two donkeys pulling carts through the narrow streets: Riace’s eco-traditional refuse collection. One of the men was Italian, a man whose ancestors built the village a thousand years ago; the other an immigrant from Ghana who, with his wife and two sons made the dangerous crossing to Lampedusa.

Before immigrants like this arrived in Riace, buildings were empty and falling into disrepair; Riace was turning into a ghost town. But the migrants from Africa rebuilt them fro their families. Their presence meant that the village school, threatened with closure, stayed open as well.

Riace’s school was able to stay open because of the immigrants’ children

The immigrants – from Africa, the Middle East and Afghanistan – do jobs that Italians no longer want to do: they look after old people, or work in the olive groves for the olive oil cooperative. A Somali has opened a restaurant, while others work as translators or in shops and workshops. One settler makes traditional Riace pottery decorated with fine coloured stripes – suggesting that immigration, rather than diluting local culture, can help the rural way of life and craft traditions to survive.

Riace neighbours

The financial aid that asylum-seekers receive also feeds the local economy because this money is mostly spent in local shops. Since these benefits often arrive late, Riace prints its own banknotes with pictures of Martin Luther King, Che Guevara and Gandhi on them. You can buy groceries and clothes with this currency. Every so often the retailers cash in their Gandhis for real euros. When Mayor Lucano ran for election he had a slogan: ‘The poorest people in the world will save Riace and we will save them.’

Perhaps one day the world, our world, won’t be upside down, and then any newborn human being will be welcome. Saying, ‘Welcome. Come. Come in. Enter. The entire earth will be your kingdom. Your legs will be your passport, valid forever.

– Eduardo Galeano

The sign at the entrance to Riace reads ‘village of welcome’

The Mayor of Riace eats with a refugee family

These days – to return to the seasonal analogy of It’s a Wonderful Life – we all live in Pottersville. But the example of these two villages suggests we can live a different way, adhering to less selfish, less materialistic values, less beholden to private profit. Some may regard extolling the example set by the villagers of Marinaleda and Riace as misguided utopianism. But I know where I would rather live.

Il Volo (Flight)

This YouTube video is a clip from a Il Volo, documentary dedicated to Riace in 2009 by the German film director Wim Wenders (no subtitles, unfortunately). This explanation is from the Mubi website:

Wim Wenders’ film Il Volo (Flight) documents an admirable example of a welcome that began over 10 years ago in Calabria, when a group of Kurds settled down in Riace, on the Calabrian coast. The German director’s initial project, a seven-minute short from an original story by Eugenio Melloni, turned into a 32-minute hybrid of documentary and fiction after Wenders met a young Afghani refugee. Il Volo became a firsthand account, with Wenders’ off-camera narration, of immigration as a resource. ‘What was happening to these people was much more important than the fiction I was making,’ said Wenders, in Rome to present the film. Commissioned by the Calabria Region and co-produced with the local Film Commission and with support from the High Commissioner of the United Nations, the film was shot in 3D.

AFP news agency report on Riace

Follow link to open in YouTube

See also

Marinaleda

- Spain’s communist model village (Guardian)

- Spanish ‘Robin Hood’ mayor vows to continue food raids (Telegraph)

- Workers’ cooperative defies crisis (Press Europe)

- A Job and No Mortgage for All in a Spanish Town (New York Times)

- 27% of Spaniards are out of work. Yet in one town everyone has a job (Independent)

- The Village Against the World: new book about Marinaleda by Dan Hancox (Amazon)

Riace

- Italian mayor saves his village by welcoming refugees (BBC)

- The tiny Italian village that opened its doors to migrants who braved the sea (Guardian)

- Migrants bring new life to a village in southern Italy Guardian

It’s a Wonderful Life: previous posts

Walking Capri: ‘a tiny morsel of an island but exquisite’

I caught an early morning hydrofoil from Naples to Capri, one of the few passengers not hailing from Japan. Back home in Liverpool, the temperature had barely edged into the teens; here, the sun shone in an azure sky and the mercury was headed for the twenties. In the day ahead, on three blissful walks on the island, I would feel that I was in paradise – and have a fateful encounter with kids (of both sorts).

As the boat pulled away across the Bay of Naples, there were stunning views of Vesuvius and the Sorrento coastline. The hydrofoil makes short work of the crossing, and 40 minutes after leaving Naples we were negotiating the approach to the Marina Grande as the dramatic form of this small and mountainous island, dominated by the peak of Monte Solaro, rose from the sea.

The island of Capri reminded me of a cloud. It was a silver stain above the expanse of limitless blue sea and sky. A south wind blew over the waters of the Mediterranean, drawing the moisture that gathered in thick fog on its flanks and on its heights …. An air of unreality hung over the place.

– Norman Douglas, South Wind

My plan was to do two walks out to the eastern end of the island – a loop first along the spectacular Pizzolungo coastal path to take in two of the island’s iconic sights – the Natural Arch and the Faraglioni rocks; and then a walk out to Villa Jovis, the largest and best conserved of the 12 villas which the Emperor Tiberius had built on the island.

From the harbour it’s a steep climb up a thousand steps to the main town, where the main square and surrounding streets of prestigious shops are bustling and crowded. It’s here that the image of Capri as a rich person’s paradise and a tourist nightmare might be confirmed.

But you only have to walk out for five minutes or so along the lanes of the town, edged with town houses, villas and allotments where vines were underplanted with potatoes and artichokes, to be almost alone, apart from the occasional resident walking back from town with their morning shopping.

Land is at a premium on this rocky island, and this practice of utilising every square foot of cultivable soil is deeply rooted: as I walked out along the Via Pastena, a ceramic wall plaque informed me that the ‘pastinato’ was an agricultural contract introduced to Capri by the Benedictines which involved the clearing of waste land using a ‘pastino’, a two-pronged iron implement suitable for breaking up the hard soil. Another lane, Via Tragara, displayed a plaque telling that the name originated in the Greek ‘tragarion’, meaning a goat pen. Goats – they were have a particular significance for me on this day.

Although walking on Capri involves a fair amount of up-and-down, virtually all the paths are paved or stepped, being effectively extensions of the lanes and alleyways of Capri town. As I walked out along these lanes, the air was filled with the intoxicating fragrance of wisteria which appeared to be the signature spring blossom of Capri.

Gallery: the wisterias of Capri

Leaving the walls of the town lanes behind, a pleasant walk along the paved path through pine trees with glimpses of the sea beyond brought me to a magical place.

Hanging high above the turquoise sea, is a gigantic arch of natural rock, the result of the collapse of a cave (probably, in pre-historic times when Capri was still part of the mainland) and of the action of wind and rain that, in the course of time, have moulded the arch into its present shape.

There’s a small viewing platform with a bench where I sat for some time, alone and undisturbed, before setting off on the return leg of the walk.

The footpath, which hugs the precipitous coastline, offers at every turn a succession of quite amazing views of the sea, the Sorrentine peninsula and another of the island’s iconic natural wonders – the Faraglioni. I met only the occasional walker as I made my way along the spectacular path, taking in views of the sea and cliffs, and absorbing the scents of pine and wild flowers and birdsong in near solitude.

Hidden from view along this stretch are many luxurious villas. The most famous of them is, though, fully visible on a promontory far below. Built in 1937 for the writer Curzio Malaparte (whose politics veered all over the place, and who was repeatedly imprisoned by Mussolini), it’s a bold piece of modern architecture designed by the Italian modernist architect, Adalberto Libera, and completely dominates the rocky spur of Punta Masullo.

The villa sits on a dangerous cliff 32 metres above the sea and access can only be gained either by foot from Capri Town or by boat via a staircase cut into the cliff. Casa Malaparte’s interior and exterior (particularly the rooftop patio) were prominently featured in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film, Contempt (Le Mépris). The villa was abandoned and neglected after the death of Malaparte in 1957. It suffered both from vandalism and natural elements for many years and was seriously damaged before renovation started in the early 1990s. Much of the original furniture, too large to remove, remains, along with the marble sunken tub in the bedroom of his mistress and Malaparte’s book-lined study.

Gallery: spring flowers of Capri

Further on, I arrived at the Tragara viewpoint that overlooks the Faraglioni – the collective name for three craggy pinnacles of rock that rise from the sea just off the coast.

I headed back towards the town along Via Tragara, walking past elegant residences and luxurious hotels, all set in beautiful Mediterranean gardens. Interestingly, one of these hotels – formerly known as the Villa Vismara – was designed by Le Corbusier. It was built in the 1920s as the residence of an eminent Italian engineer Vismara and his family. A plaque records that during the Second World War the villa served as the headquarters of General Eisenhower, where he and Winston Churchill met to discuss strategy. They certainly knew how to pick a venue!

Further along Via Tragara I passed villas where Rainer Maria Rilke (in 1907-8) and Pablo Neruda (in the 1950s) once stayed. At first, Rilke wasn’t impressed with the island. He wrote to his wife: ‘I am always rather depressed in such displays of landscapes before this clear, prized, unassailable beauty. Here both people and landscape are united in a boring measure of cheap rapture’. But he grew to like the place and during his stay on Capri he wrote a small collection of lyrical prose entitled ‘Notes from Naples and Capri’, as well as several poems, including ‘Song of the Sea’:

Timeless sea breezes,

sea-wind of the night:

you come for no one;

if someone should wake,

he must be prepared

how to survive you.

Timeless sea breezes,

that for aeons have

blown ancient rocks,

you are purest space

coming from afar…

Oh, how a fruit-bearing

fig tree feels your coming

high up in the moonlight.

Better, no doubt, in the original German.

Neruda arrived on the island in 1953, a political exile from his native Chile, staying as the guest of Italian historian Edwin Cerio at the splendid Casa di Arturo on the Via Tragara. During his time on the island he published The Captain’s Verses, a collection of passionate love poems addressed to his secret lover, Matilde Urrutia, the one ‘with the fire/of an unchained meteor’. ‘We came to the marvellous island on a winter night’, he wrote in his Memoirs. ‘The coast loomed through the shadows, whitish and tall, unfamiliar and silent. What would happen? A little horse carriage was waiting. Up and up the deserted night time streets the carriage climbed. White, mute house, narrow vertical lanes’.

For Neruda, the time on Capri was a romantic idyll. He and Cerio, then in his late eighties, went for long walks. ‘Among the rocks, wherever the sun beat down most, in the arid earth, diminutive plants and flowers burst out, grown in precise and exquisite patterns’. They learned where to find the best wine and olives. In the mornings Neruda worked on his poems and in the afternoon Matilde typed them. It was the first time that she and Neruda had lived together in the same house: ‘In that place whose beauty was intoxicating, our love grew steadily. We could never again live apart’ (quotations from Reflections on Blue Water: Journeys in the Gulf of Naples and in the Aeolian Islands by Alan Ross).

Here’s one of the poems from The Captain’s Verses, ‘Wind on the Island’:

The wind is a horse:

hear how he runs

through the sea, through the sky.

He wants to take me: listen

how he roves the world

to take me far away.

Hide me in your arms

just for this night,

while the rain breaks

against sea and earth

its innumerable mouth.

Listen how the wind

calls to me galloping

to take me far away.

With your brow on my brow,

with your mouth on my mouth,

our bodies tied

to the love that consumes us,

let the wind pass

and not take me away.

Let the wind rush

crowned with foam,

let it call to me

and seek me galloping in the shadow,

while I, sunk

beneath your big eyes,

just for this night

shall rest, my love.

Near to Cerio’s villa stands a plaque, upon which are lines in Spanish by Neruda. A rough translation might be:

Capri, queen of rock,

in your dress

the colour of amaranth and lily

where lived,

experiencing

happiness and pain, the vine brimming

with radiant clusters

that conquered the earth

Back on the town lanes, I set off on a second walk out to the eastern end of the island. This time the objective was the ruins of the Villa Jovis, built for the Emperor Tiberius. As I walked out of town, I caught glimpses, through wrought iron gates, of the beautiful homes and immaculate gardens, many of which were entered beneath trellises smothered in wisteria (see the gallery, above).

I paused at this little store where I bought a lemon granita, the delicious and thirst-quenching drink served from a gelato machine as a slush of coarse ice crystals with no added sweetening. Sitting on wall spooning this heavenly concoction as the sun shone and enveloped in a bouquet of wisteria perfume, this was the moment when I felt I was in paradise. A little electric truck of the kind you encounter frequently on these narrow lanes, delivering parcels and packages, went by; standing erect on the loading platform was a local man, hitching a ride back from the supermarket.

The path out to the Villa Jovis is bordered by limestone walls and shaded by pines. Lizards are frequently disturbed from their slumbers, slithering off into hidden recesses.

Just before the entrance to the Villa I had my first encounter with a small flock of goats. I was to meet them again on my way back, and distracted by their antics, suffer a minor calamity.

Villa Jovis was completed in AD 27. Tiberius mainly ruled from there until his death in AD 37, some sources suggesting that he preferred Capri to Rome where he feared assassination. Villa Jovis is the just the largest of twelve villas built for Tiberius on Capri that are mentioned by Tacitus.

It’s a spectacular site, extending over some 7,000 square metres (including 3,000 square metres of gardens). The place has been described as a vast pleasure complex designed to pander to the emperor’s lavish and (according to many Roman sources) debauched desires.

The site includes imperial quarters and extensive bathing areas set in dense gardens and woodland. Spectacular the site may have been, but on an island with no natural water supply the villa’s location posed major headaches for Tiberius’ architects. In order to collect and store enough rainwater to supply the villa’s baths and 3000-sq-metre gardens, a complex canal system was constructed to transport rainwater to four giant cisterns or storage tanks, the remains of which are still clearly visible today.

The site lay abandoned from the first century AD until the first archaeological exploration took place in 1827. The structure, built to an unusual height, consisted of a number of different floors terraced along the natural slope of the land. The various living and administration area were laid out around a central area that held the large cisterns for gathering rain water, the sole source of drinking water and also a reserve used to supply the baths to the south, which were divided into the traditional frigidarium, tepidarium and calidarium areas.

The imperial quarters were on the eastern side, in the highest, best protected part of the complex, completely isolated from the rest of the structure, connected only by ramps and stairways to the balcony on the northern side. The balcony, designed for walking and viewing the stunning panorama of the entire Gulf of Naples, from the Island of Ischia to the Sorrento peninsula, was where I sat and ate my lunch.

While Tiberius was on Capri, rumours abounded of lurid tales of sexual perversity, including graphic depictions of child molestation, and cruelty, and of his paranoia. A stairway leads from the villa to the 330 metre-high Salto di Tiberio (Tiberius’ Leap), a sheer cliff from where, according to contemporary Roman sources such as Suetonus, Tiberius ordered children and young men who had been forced to participate in orgies to be hurled into the sea. Some modern historians contest this as exaggeration, but Suetonius’ portrayal of Tiberius in his Lives of the Caesars probably reflects the Roman view of the emperor at the time:

After retiring to Capri, where he had a private pleasure palace built, many young men and women trained in sexual practices were brought there for his pleasure, and would have sex in groups in front of him. Some rooms were furnished with pornography and sex manuals from Egypt – which let the people there know what was expected of them. Tiberius also created lechery nooks in the woods and had girls and boys dressed as nymphs and Pans prostitute themselves in the open.

The view today from the villa complex towards the easternmost tip of the island gives a sense of how houses and cultivated gardens cover every square inch of usable land.

I began to retrace my steps back to Capri Town. Where I had seen the goats earlier, a party of schoolchildren with their teachers were seated along a low stone wall having a picnic lunch. The goats were engaged in making repeated forays, seizing bags of crisps and pieces of baguette off the kids. Distracted by the sight, I missed a step and went sharply over on my ankle, hearing what sounded like a crack.

It felt bad and I sat for five minutes on the wall to recover. But when I stood, it seemed OK and I found I could walk unimpeded. I walked (probably stupidly) for another three hours – out past the second town of the island, Anacapri, and along Via Migliera, a pine-shaded lane which makes its way through vineyards, patches of ancient woodland and citrus groves. There are glimpses of the sea and the island of Ischia before you finally reach the Punta Carena lighthouse at Faro.

By now I was hobbling, so I caught the tiny bus back to Capri Town, staggered down the thousand steps to the port and caught the hydrofoil back to Naples. The footnote (sorry!) to this story? When I got back to Liverpool, I took myself to A&E where an x-ray revealed a broken ankle. I was lucky, though: it’s only a small crack in the outer surface of the ankle bone, so I was soon out of plaster and off crutches. Instead, for a month or so, I must wear a formidable padded boot, a magnificent work of engineering that gives me limited mobility, though prevents me driving the car.

It’s a shame that such a wonderful day on this beautiful island should now have this memory associated with it. But, like Maxim Gorky, who lived on Capri for more than seven years until 1913, I will always recall the island in this way:

Capri is a tiny morsel of an island but exquisite. Here you see right away, in a day, so much beauty that you remain inebriated and cannot accomplish anything. The Gulf of Naples is more beautiful and deeper than love and women. In love you discover everything right away. Here I am not sure if is it possible to discover everything. In my brain, a happy devil is dancing the tarantella. In Capri I feel drunk without having touched wine…

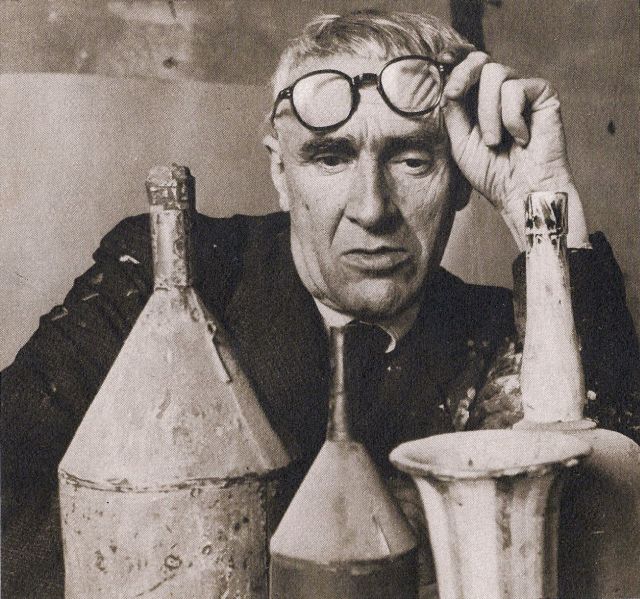

Giorgio Morandi: Lines of Poetry

It was snowing heavily as we made our way from Highbury Corner to the Estorick Collection Gallery. London looked different, with colours drained to monochrome whites, blacks and greys. We were about to see an exhibition of work by the Italian artist Giorgio Morandi, whose paintings and drawings are characterised by a similarly reduced palette and an economy of line.

Drawing on a number of private collections, Lines of Poetry is an exhibition of almost 80 etchings and watercolours by the master of poetic understatement, Giorgio Morandi. Shy and retiring, and a man who lived a simple life, almost as spartan as his pictures, Morandi was entirely self-taught as a printmaker, but quickly mastered the technique and went on to be professor in the discipline for more than 20 years in Bologna. The subject matter of Morandi’s work may be restricted, but his still lifes and landscapes reveal his technical brilliance and, as de Chirico observed, the poetry in things that seem so familiar that we ‘often look upon them with the eye of one who sees but does not understand’.

This was the first time that I had visited the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, a small gallery housed in a Georgian house on Canonbury Square which celebrates its 15th anniversary in 2013. The gallery was founded by Eric and Salome Estorick, American art collectors who amassed a significant collection of modern Italian art, all of which was donated to the Foundation which now bears their name. The house in Canonbury Square was purchased in 1994 and refurbished to house the collection, along with an art library. Giorgio Morandi has proved to be one of the Estorick Collection’s most popular artists.

Giorgio Morandi was born in 1890 in Bologna, where he lived in the same house for the rest of his life, with his mother and three sisters. He worked and slept in a single room, surrounded by the dust-laden objects he portrayed in his paintings. Every summer, the family went to Grizzana, in the Apennines about 30 kilometres southwest of Bologna. Morandi himself said, ‘I have been fortunate enough to lead…an uneventful life’.

Morandi once spoke of spending his life in Bologna, ‘this town of the old university, the ancient towers, the arcades, the orderly, quiet, provincial atmosphere’. The house he lived in became his world. Yet he also lived through two world wars and through a period of social and political upheaval in Italy. He served in the army in the First World War and lived under German occupation in the Second World War.

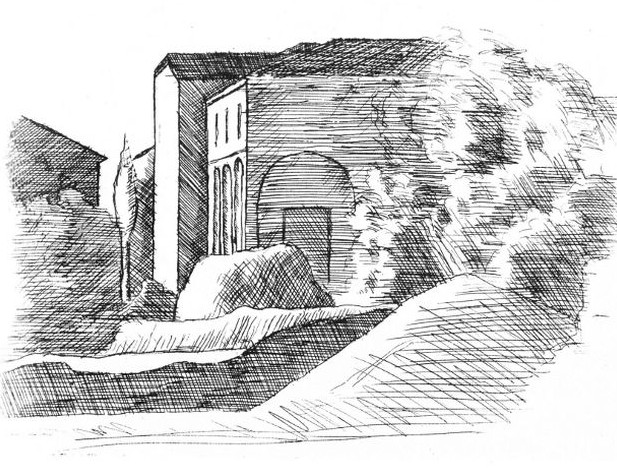

Even though he lived his whole life in Bologna, Morandi was open to influences from other artists, including Derain, Picasso, and especially Cézanne. After a trip to Florence in 1910, he absorbed influences from past artists such as Giotto, Piero Della Francesca, and Paolo Uccello. He taught drawing in elementary schools from 1916-29, a period when he was briefly associated with the metaphysical painting movement, best known through the enigmatic still lifes of Giorgio de Chirico. After Mussolini came to power, Morandi’s closest ties were with the rustic Strapaese movement which advocated a return to local cultural traditions. In 1930 Morandi became Professor of Etching at the Accademia di Belle Arti, and his works began to be shown abroad.

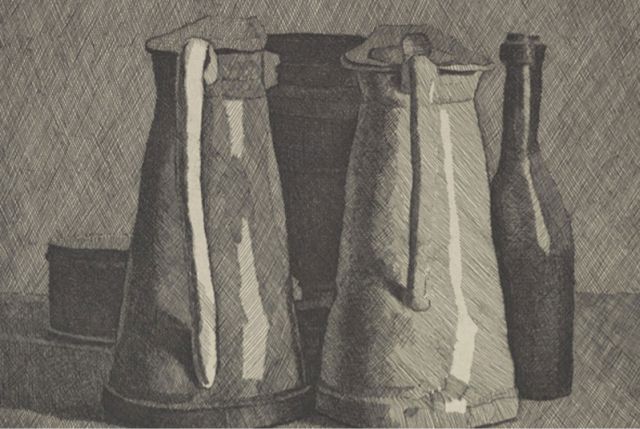

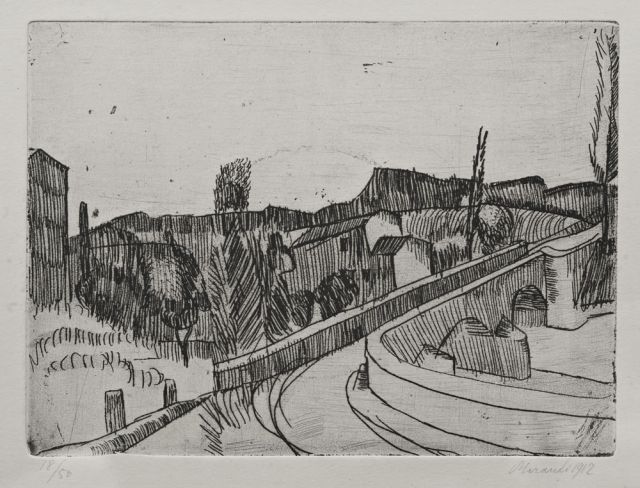

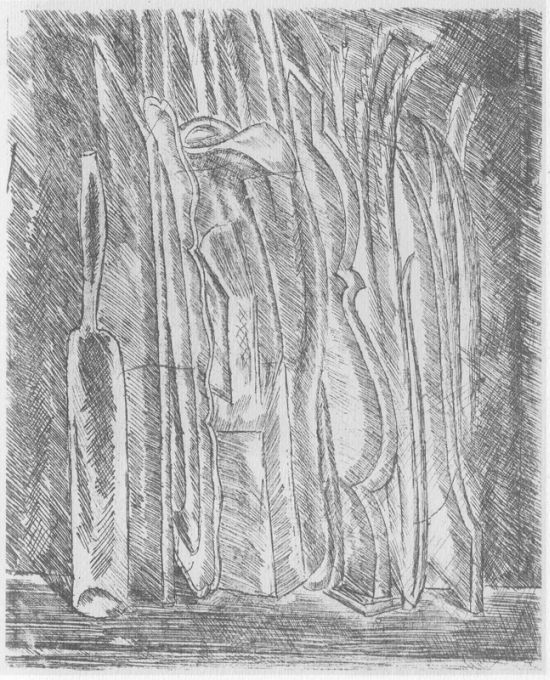

Lines of Poetry presents a chronological account of the artist’s development, beginning with his debt to Cézanne, as seen in an early etching such as ‘The Bridge on the Savena in Bologna’, a study of form in the landscape in which Cézanne can be seen as the model. A cubist phase follows in ‘Still Life with Bottles and Pitcher’ from 1915, but by the 1920s Morandi’s distinctive approach to composition emerges in a landscapes such as ‘Tennis Court at the Giardini Margherita’ and Landscape with Large Poplars (1927), in which Morandi seems to treat the lines of tall poplars as an element in an arrangement of forms in much the same way as his still lifes of of this period with their elongated forms .

There are two fine landscape etchings from this period, both views of his native Bologna in which areas of pure white are contrasted with thickly etched lines: ‘Landscape (The Chimneys of the Arsenal on the Outskirts of Bologna)’ (1927) is an industrial vista whose horizon is broken up by factory chimneys rising over suburban roofs, while ‘Three Houses in Campiaro, Bologna’ (1929) is a study of the rectangular shapes of the buildings contrasted with the softer, natural forms of trees and shrubs.

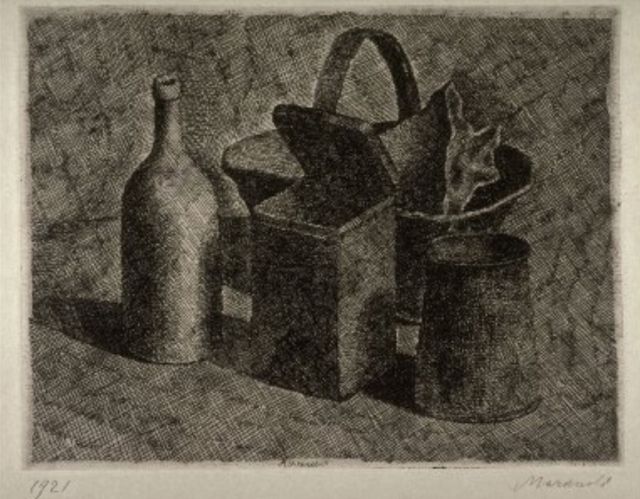

Here, too are three still lifes from 1921: ‘Still Life with Basket of Bread’ – with bottle, squat vase, open tin and basket depicted in deep shades of cross-hatching with the texture of cloth – and the exquisite ‘Still Life with Sugar Bowl, Lemon and Bread’ and ‘Still Life with Bread and Lemon’. They are simple, mysterious, and atmospheric. It around this time that Giorgio de Chirico wrote of Morandi:

We are not a people suited to growing complacent in bourgeois existence. The richest and most content of our bourgeoisie always have, at the bottom of their nature, something more unquiet and restless than the poorest peasant of more northerly and happier lands that are less warm and less bright. That this fatal melancholy sharpens our vision of the world is an undeniable fact. Italian art, in its more skeletally beautiful aspects is a hard, clean and solid thing. From such denuded forms, cleansed of unrestrained enthusiasm and improper joy, is born that chaste, austere and lofty spirit which represents the highest merit of our great painting from the primitives to Raphael. Today, the confusion which oppresses the arts is enormous; and the poor quality of the painting that floods the continents with torrents of greasy, oily colour is difficult to define. There is an abundance of foolishness, much lack of understanding, a great deal of banality and cheap sensuality – and as for spirit, one would search for it in vain.

Therefore, it is with sympathy and a great sense of comfort that we have followed the emergence, development and maturing of artists such as Giorgio Morandi through their slow but sure labours.

He seeks to discover and to create everything alone: patiently grinding his colours, preparing his canvases and looking at the objects that surround him, from loaves of ‘sacred bread’ – dark, and riven with cracks like the surface of an ancient rock – to the clean forms of glasses and bottles. He looks at a collection of objects set on a tabletop with the emotion that shook the heart of the traveller in ancient Greece when he gazed upon woods, valleys and mountains believed to be the realm of beautiful and surprising deities.

He looks with the eye of one who believes, and the innermost skeleton of these things – dead for us, since immobile appears to him in its most consolatory aspect: in its eternal aspect. In such a way he engages with the great lyricism created by the most profound European art: the metaphysics of the most commonplace objects. Of those objects that habit has rendered so familiar to us that we often look at them with the eye of one who sees but does not understand. … In his ancient Bologna, Giorgio Morandi sings in this way – in an Italian way – the song of the great European craftsmen. He is poor, since the generosity of art lovers has thus far eluded him. And in order to be able to continue with his work with purity in the evenings, in the bleak rooms of a state school he teaches youngsters the eternal laws of geometric design – the foundation of every great beauty and of every profound melancholy.

I love that line: ‘He looks at a collection of objects set on a tabletop with the emotion that shook the heart of the traveller in ancient Greece when he gazed upon woods, valleys and mountains believed to be the realm of beautiful and surprising deities’.

Morandi’s friend Raffaello Franchi later recalled visiting the house in Bologna:

I recall his house as it appeared to me the first time I saw it, divided into two parts – two worlds. In the first – neat and tidy, with a mirror sheen – lived his mother and sisters. In the second lived the artist with his work – and one could not call it dirty only because the thick dust that covered everything was the result of a religious respect for sacred things: the piece of dried bread on a stool, the mother-of-pearl shell he might have gathered … and the jug stolen from his mother’s kitchen …

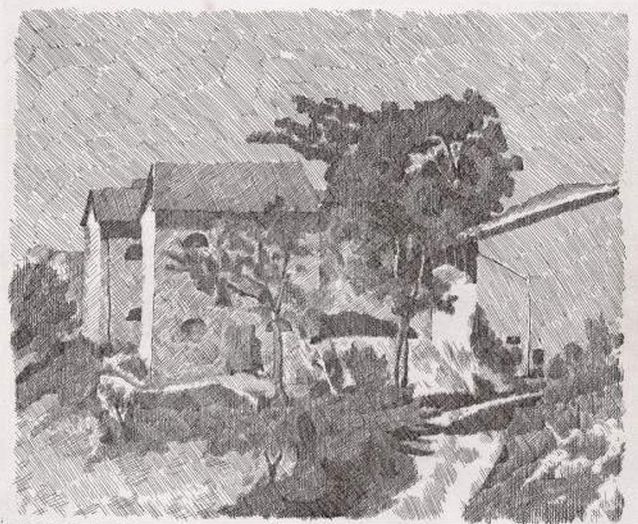

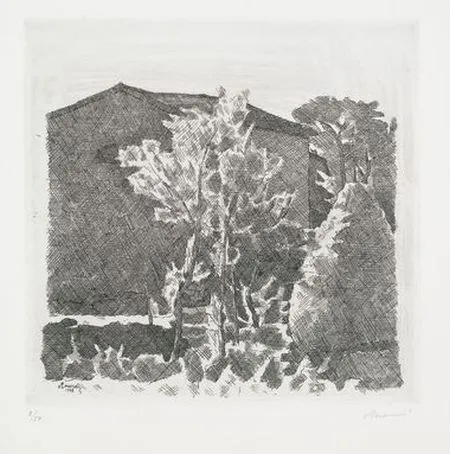

From the late 1920s come several lovely etchings that evoke the landscapes around the holiday home in Grizzana: ‘Hillside in the Morning’ and ‘Hillside in the Evening’ (both 1928), and ‘Grizzana Landscape’ (1932). The art critic Luigi Magnani described Morandi as seeing Grizzana ‘wrapped in a halo of poetry’ where ‘large spaces were offered to his gaze: hills, meadows, forests … to Morandi it was blessed’.

Morandi gained international acclaim after the Second World War, rapidly becoming one of the most respected Italian painters. In 1956 he travelled outside Italy for the first time. Morandi’s high profile in Italy was shown when Federico Fellini’s featured his paintings as the epitome of cultural sophistication in La Dolce Vita in 1960. By this time, however, Morandi had withdrawn to work in his studio at Grizzana. He died in Bologna on 18 June 1964.

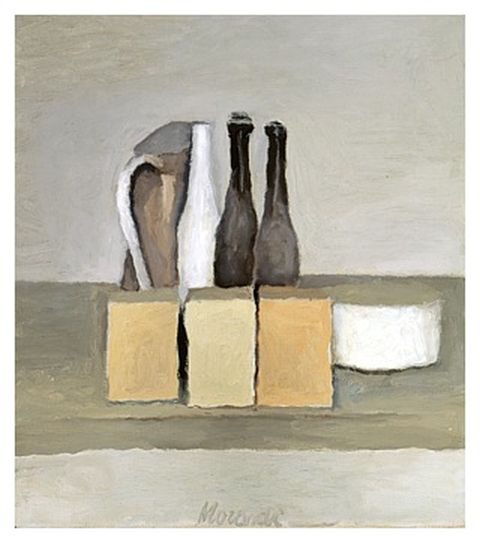

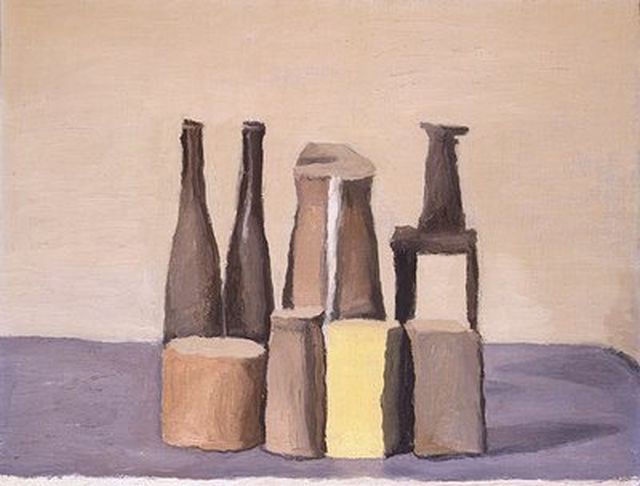

Morandi controlled every aspect of making a painting, from stretching his own canvases and making his paints (which meant he could maintain precise control over his palette), to placing his objects, lighting them and positioning himself before them. The objects he chose to paint – bottles, jars, jugs and cans – were placed on sheets of paper on specially made tables and shelves and their position marked out in pencil. He endlessly arranged and rearranged the same objects—bottles, tins, and boxes collected from the shops near his home—in search of new combinations and formal possibilities.

‘Nothing is more abstract than reality,’ Morandi declared. The restrictions of his subject matter and of monochrome etching forced him to focus on the relationships between objects, and between objects and light. He studied the beauty in small things.

It takes me weeks to make up my mind which group of bottles will go well with a particular coloured tablecloth. Then weeks thinking about the bottles themselves, and yet often, I still go wrong with the spaces. Perhaps I work too fast.

Josef Herman, a friend of Morandi, recalled visiting his studio:

The floor was by far the most cluttered part of the room; … littered with bottles, all different sizes, shapes and colours. I had no difficulty in recognising some of the bottles I had seen in Morandi’s paintings; only in the paintings they possessed a dignity and a life of their own … The live bottles had nothing of the kind. The nobility of the colours and the textures was obviously an invention of Morandi’s.

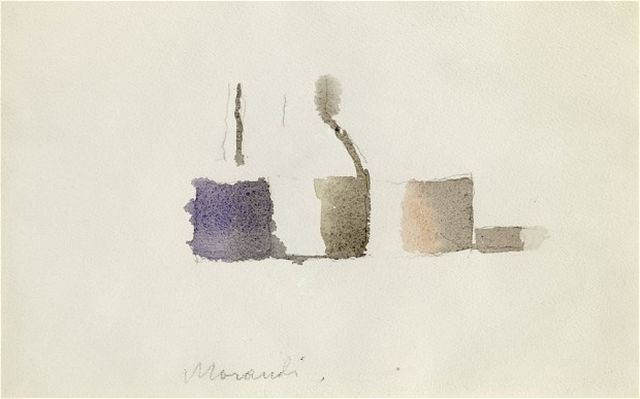

In Morandi’s still lifes of the 1950s and 60s, objects are reduced to near-abstraction: cylinder, cone, sphere. Like Cezanne, Morandi favoured the pared-down yet spontaneous medium of watercolour. A highlight of this exhibition is a group of rarely displayed watercolours in which less is more: a few barely discernible pencil lines and three quick smears of muted colour in ‘Still Life’ (1960), and fragile outlines bathed in shadow and light, just discernible as landscape in ‘Landscape (Levico)’ and ‘Landscape (House in Ruins)’ from 1957-58.

Giorgio Morandi may have lived a simple life, but he did not make simple art. He altered the colours of bottles, bowls and vases before arranging his still lifes. He played with shadows, scale and light. In a 1955 radio interview he explained: ‘I want to communicate those images and feelings that the natural world awakens in us.’ Three still lifes from 1955-56 (not in the exhibition) seem to bear this out:

Here are two trailers for the documentary Giorgio Morandi’s Dust, which is screened at the Estorick exhibition. It presents the life of Morandi through his still lifes and landscapes and the eyes of friends and critics.

Giorgio Morandi’s Dust – International Trailer w/English subs from Imago Orbis on Vimeo.

This YouTube video offers a slideshow of Morandi’s work.

We left the gallery to walk in Highbury Fields, with the snow still falling. We noted how everyone seemed to be smiling. Children on sledges, throwing snowballs and building snowmen. In fact, the snow seemed to have brought the artistic streak out in adults, too.

See also

- Morandi: Lines of Poetry: Guardian review

- Giorgio Morandi: Lines of Poetry: Telegraph review by Alastair Sooke

- Giorgio Morandi: The Essence of the Landscape

- Giorgio Morandi Highlights: extensive series of short video podcasts on works from each stage of Morandi’s career

Lovely Vernazza is swept away

Yesterday I received an email that shocked and saddened me. It was sent to me because I had once booked accommodation in Vernazza tha is one of the Cinque Terre or ‘The Five Lands’, the little villages that cling to the rugged Ligurian coastline between Genoa and La Spezia.

The email told that on 25 October 2011 Vernazza was the victim of massive flooding and mudslides that killed 3 residents, and left the town buried in over 13 feet of mud and debris. We spent an idyllic 4 days there at Easter in 2007, enjoying the character and tranquillity of a village which is accessible only by rail, ferry or on foot. NowVernazza has been horribly damaged. The residents have been evacuated leaving just volunteers and emergency crews to begin the cleanup. The road to rebuilding is expected to be long, complicated and costly.

These YouTube clips show the terrifying force of the flood that swept down the steep surrounding hillsides and into the village, sweeping cars out to sea and burying the ground floor of shops and houses in mud and rubble.

When I got the email, it occurred to me that I must have missed reports of this disaster on the TV news and in the newspapers. But a quick search on Google revealed that there was no coverage anywhere in the UK media, apart from one report in The Telegraph.

The Cinque Terre is composed of five villages: Monterosso (which also cought the full force of the flood), Vernazza, Corniglia, Manarola, and Riomaggiore. The coastline, the five villages, and the surrounding hillsides are all part of the Cinque Terre National Park and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. For us, the great attraction of the area was the fact that you can walk from one village to the next by well-marked trails, and return to you starting point by train or ferry.

Vernazza is perhaps the prettiest of the villages (though it’s a difficult call), with its pastel-coloured buildings, situated in the shelter of a rocky cove whose dark rocks make a dramatic contrast to the brightly coloured houses. Like all the Cinque Terre communities, it’s a working fishing village and in the harbour fishermen tend their boats, some – invariably occupied by a tribe of sleeping cats – drawn up on the little piazza that overlooks the port. The cobbled main street is lined with cafes and small shops, and was once the bed of a stream that is now culverted beneath the cobbles. At the top of the street is the railway station, and beyond that the parking place which forms the nearest point that can be reached by car. Little alleyways ascend steeply from either side of the main street, and it was several hundred feet up one of these side passages where our accommodation was located.

Vernazza was founded about 1000 A.D. and was ruled by the Republic of Genoa from 1276. Above the village are the ruins of medieval fortifications, built in the 16th century to protect the village from pirates, and the church of Santa Margherita d’Antiochia, built in 1318. A 45 minute walk – quite steep in places, but with fantastic views – along the coastal trail brings you to Monterosso, another wonderful village with its main square right on the waterfront and a very small sandy beach.

I’ve put together a slideshow of some of the photos I took of Vernazza during our trip. They record a day in the life of this laid-back village – the first stirrings on the main street and port piazza, with locals and tourists waiting for the first ferry along the coast, the streets and alleyways, to the golden glow of the setting sun illuminating the colourful houses, before finally the suns sets behing the headland.

Click the first image to launch the slideshow.

Here is an evocative video shot by the American travel writer Rick Steves walking down the main street just after 10:00 at night.

Meanwhile crews are hard at work in Vernazza, excavating enormous amounts of earth to uncover streets and the ground floors of buildings. The next priority will be to rebuild the town’s infrastructure. Electricity, gas, water and sewer services will be slow to return to Vernazza. In many cases, engineers will need to evaluate the safety of structures before they can be used again. Only then can homes and business begin to clean out, remodel and reopen.

In the meantime, Vernazza’s residents have been evacuated. Entry to the town is restricted to the military and people working with relief crews. The road leading to Vernazza has been wiped out by slides, boat service has been curtailed, and there is no public train service. Vernazza is expected to remain closed at least until the spring, but there is a determination to recover and to draw in the tourists again. We certainly hope to back, soon.

Links

- A Violent Rain Buries an Italian Friend (Rick Steves)

- Alluvione Vernazza: auto e furgoni risucchiati: incredible video

- Italians open investigation into flooding of Cinque Terre: the only British coverage I could find (The Telegraph, 28.10.2011)

- Photos of the disaster from Vernazza resident (Facebook)

- Vernazza & Monterosso digging out: Rick Steve’s update 11.11.2011

- Save Vernazza ONLUS: dedicated to the restoration and preservation of Vernazza

- An Incredible Story of Courage in the Face Of Death: A Personal Account of Tragedy Caused by the Vernazza Flood

Garrone’s Gomorrah

Why do I do this? Only 24 hours after watching the bleak Winter’s Bone, I decided to dig out Gomorrah, recorded a few weeks ago when broadcast on BBC4. Matteo Garrone’s film, which won the grand prize at Cannes 2008, weaves together the disparate stories of some of those caught in the web of the Camorra, the crime syndicate that is the Naples equivalent of the Mafia. It is a long way from the romanticism of The Godfather or the comfortable domesticity of The Sopranos. It is irredeemably bleak: from the opening scene of a mob killing to its closing scene in which two central characters are killed and their bodies disposed of like the waste whose disposal the Camorra controls, there is no hope.

Gomorrah is based on a best-selling expose of the Camorra by Roberto Saviano, who went undercover, used informants, and even worked as a waiter at their weddings. His book named names and explained exactly how the Camorra operates. He now he lives under 24-hour armed guard.

Gomorrah follows five disconnected stories; there’s the innocent-looking boy, Toto, who wants to be a gang foot-soldier; Don Ciro, a bagman who scuttles along the walkways of the nightmarish housing projects doling out cash to families of faithful Camorra members; Pasquale, an expert tailor on a couture-house shopfloor, who dares to moonlight giving lessons the workers of a rival Chinese gang master; and two doomed young delinquents who fancy themselves as gun-toting outlaws.

Most significantly, the fifth story shows the Camorra’s respectable face, represented by Franco, whose business is the disposal of toxic waste as landfill. The Camorra is larger than the Mafia: its annual revenues are said to be as much as $250 billion, and the closing titles suggest that the organisation has invested in the rebuilding of the World Trade Centre.

Roberto Saviano’s book revealed the sheer scale of the Camorra’s activities, not just areas like drugs, people trafficking and gun running, but also in businesses that superficially seem legitimate: fashion, construction, waste disposal. In the film, there are many scenes in which large amounts of money are counted and change hands. In his book, Roberto Saviano wrote:

The Casalesi have distributed their good throughout the region. Just the real estate assets seized by the Naples DDA in the last few years amount to 750 million euros. The lists are frightening. In the Spartacus trial alone, 199 buildings, 52 pieces of property, 14 companies, 12 automobiles, and 3 boats were confiscated. Over the years, according to a 1996 trial, Schiavone and his trusted men have seen the seizure of assets worth 230 million euros: companies, villas, lands, buildings, and powerful automobiles, including the Jaguar in which Sandokan was found at the time of his first arrest. Confiscations that would have destroyed any company, losses that would have ruined any businessman, economic blows that would have capsized any firm. Anyone but the Casalesi cartel. Every time I read about the seizure of property, every time I see the lists of assets the DDA has confiscated from the bosses, I feel depressed and exhausted; everywhere I turn, everything seems to be theirs. Everything. Land, buffalos, farms, quarries, garages, dairies, hotels, and restaurants. A sort of Camorra omnipotence. I can’t see anything that doesn’t belong to them.

The most striking element of the film for me was the combination of cinematography with eye-boggling locations. Matteo Garrone, the director, filmed in a prison-like housing project near Naples and several other bleak, ruined, urban and semi-rural locations. The housing project is a fearful place, with many apartments blasted or burned out, where residents barricade themselves inside their apartments behind bolts and bars. The camera creeps nervously along the project walkways amidst constant, echoing noise as drugs are dealt to shouting crowds and the place resonates with cries from lookouts. For me, Garrone’s vision of these landscapes is redolent of the spiritual and physical desolation Antonioni captured in one of my favourite Italian films, Red Desert (1964):

Garrone’s film follows Saviano’s book in presenting the Camorra gangsters as essentially capitalists, and its focus lies on business processes rather than set-piece gangland battles or executions. This cool, dispassionate approach has led some reviewers to compare it with films by Francesco Rosi like Lucky Luciano and Illustrious Corpses.

The scenes set in the massive disused quarry where toxic waste is being buried are shot from a high angle, emphasising the monumentality of the landscape, in which trucks and men labour like ants. I knew this reminded me of something, and then it came to me – John Martin’s 19th century apocalyptic visions of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah:

In Christianity and in Islam, Sodom and Gomorrah became synonymous with impenitent sin, and their destruction with the manifestation of God’s wrath. Whether Garrone anticipates the sins of the Camorra bringing forth their own destruction, I don’t know. From his film and other evidence, it appears there is no wrath powerful enough to dislodge them.

Though there are a couple of characters in Gomorrah who make principled decisions to extricate themselves from the depravity that has literally poisoned the country, we arrive at that closing scene in which the two characters who fancied themselves as gunmen are killed and their bodies disposed of in a front-loader, toxic waste.

Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere

One warm day in 1946 I sat down on a bollard on the Molo Audace, close to the Piazza Unita, to write a maudlin essay.

– Jan Morris, Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere

On a day of downpour and flood there was nothing else to do but grab a book and hole up as the rain hammered down. I alighted on one that’s been lying around for some time: Jan Morris’s Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere, published in 2001 and stated by Morris herself to be her last book. It’s a work infused with sweet melancholy about a city where, she writes, ‘more than anywhere I remember lost times, lost chances, lost friends, with the sweet tristesse that is onomatopoeic to the place’:

Melancholy is Trieste’s chief rapture. In almost everything I read about this city, by writers down the centuries, melancholy is evoked. It is not a stabbing sort of disconsolation, the sort that makes you pine for death (Although Trieste’s suicide rate, as a matter of fact, is notoriously high.) In my own experience it is more like our Welsh hiraeth, expressing itself in bitter-sweetness and a yearning for we know not what.

Trieste, and in particular that bollard on the Audace jetty, was the symbolic focus, too, of the last book I read by Jan Morris, Fifty Years of Europe: An Album, which came out in 1997. It was a celebration of Europe in all its diversity, and of the New Europe that seemed to be emerging following the end of the Cold War. Snapshots of Europe across time and place were illuminated by Jan’s musings as, metaphorically perched on that jetty bollard, she circled back to the young officer James Morris seated on the same bollard in a smashed and divided Europe at the end of the second world war, preparing to write an essay on nostalgia. Morris concluded that the nostalgia she felt then – for the Hapsburg Mitteleuropa of shared values, a cohesive mixture of peoples and languages – was, ‘nostalgia not for a lost Europe, but for a Europe that never was, and has yet to be’.

In Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere, Morris returns to Trieste to explore the city as a world in itself, the capital of nowhere:

There are people everywhere who form a Fourth World, a diaspora of their own. They come in all colours. They can be Christians or Hindus or Muslims or Jews or pagans or atheists. They can be young or old, men or women, soldiers or pacifists, rich or poor. They may be patriots, but they are never chauvinistic. They share with each other, across all the nations, common values of humour and understanding. When you are among them you know you will not be mocked or resented, because they will not care about your race, your faith, your sex or your nationality, and they suffer fools if not gladly, at least sympathetically. They laugh easily. They are easily grateful. They are not inhibited by fashion, public opinion or political correctness. They are exiles in their own communities, because they are always in a minority, but they form a mighty nation, if only they knew it. It is the nation of nowhere, and I have come to think that its natural capital is Trieste.

What she’s getting at here (and she admits she may be romanticising somewhat) is that Trieste is a city which has found itself part of successive empires – Illyrian, Roman, Venetian, Hapsburg – and states, resulting in a cultural mix of languages, peoples and traditions. Austro-Hungarydeveloped the docks and brought the railway from Vienna, so that the city became, for a short time, a trading port with global connections. The Italians claimed it, European Jews enriched it – until the Nazis arrived and stayed long enough to deport those Jews who had not already left for Palestine.

Jan Morris is unequivocal in her detestation of nationalism:

The Europe of my dreams had never existed, above all because of nationality. If race is a fraud, as I often think in Trieste, then nationality is a cruel pretence. There is nothing organic to it. As the tangled history of this place shows, it is disposable. You can change your nationality by the stroke of a notary’s pen…or findd your nationality altered for you, overnight, by statesmen far away.

Morris extols Trieste’s relaxed and cosmopolitan flavour. Part-Austrian, part-Italian and part-Slovenian, Trieste has benefitted from the mercantile know-how of Greeks and Jews and all these ingredients of the city’s make-up are explored as she wanders the streets, squares and quays.

She also writes evocatively about the limestone plateau above the city, the Karst – its name adopted by geologists to describe all such similar limestone topographies – an ‘elemental slab’ of rock and stone above the city, whose people have been hardened by history, climate and geology. It’s a Slavic world of partisans, the Glagolitic alphabet and Hum, the self-proclaimed ‘smallest town in the world’.

Towards the end of the book, Morris remarks that she has looked at Trieste as she would look into a mirror, and to emphasise the solipsistic nature of most travel and travel writing she quotes Wallace Stevens:

I was the world in which I walked, and what I saw

Or heard or felt came not but from myself

She continues:

For years I felt myself an exile from normality, and now I feel myself one of those exiles from time. The past is a foreign country, but so is old age, and as you enter it you feel you are treading unknown territory, leaving your own land behind. You’ve never been here before. The clothes people wear, the idioms they use, their pronunciation, their assumptions, tastes, humours, loyalties all become the more alien the older you get. The countryside changes. The policeman are children. Even hypochondria, the Trieste disease, is not what it was, for that interesting pain in the ear-lobe may not now be imaginary at all, but some obscure senile reality.

Morris declares that this is her last book:

The books I have written are no more than smudged graffiti on a wall, and I shall write no more of them. Money? Enough to live on. Critics? To hell with ’em. Kindness is what matters, all along.

If it is her last, it completes an extraordinary life of travel. The book’s publication in 2001 coincided with her seventy-fifth birthday. God knows how many books she has written since that first visit to Trieste. Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere is a passionate and beautifully-written conclusion to that literary career.

As for me, when the clock moves on for the last time…now and then you may find me in a boat below the walls of Miramar, watching the nightingales swarm.