Paul Nash was 25 at the outbreak of the First World War. He would come to see himself as a messenger to those who wanted the war to go on for ever, creating some of the most devastating landscapes of war ever painted, his outrage at the waste of life expressed through his depiction of the violation of nature in landscapes that were both visionary and terrifyingly realistic.

He had been a member of that remarkable pre-war cohort at the Slade School of Art that included Christopher Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, William Roberts, Ben Nicholson and Edward Wadsworth. Nash had already gained a reputation as a painter of nocturnes and visionary landscapes when he reluctantly volunteered in September 1914, first joining the London Regiment (Artists’ Rifles) for home service only. But in February 1917, having completed officer training, he embarked for France, arriving in the Ypres Sector soon after.

Along with Nevinson and Spencer, Paul Nash is the First World War artist whom I most admire, so I was interested in Paul Gough’s account of his war years in A Terrible Beauty: British Artists in the First World War which I finished reading recently.

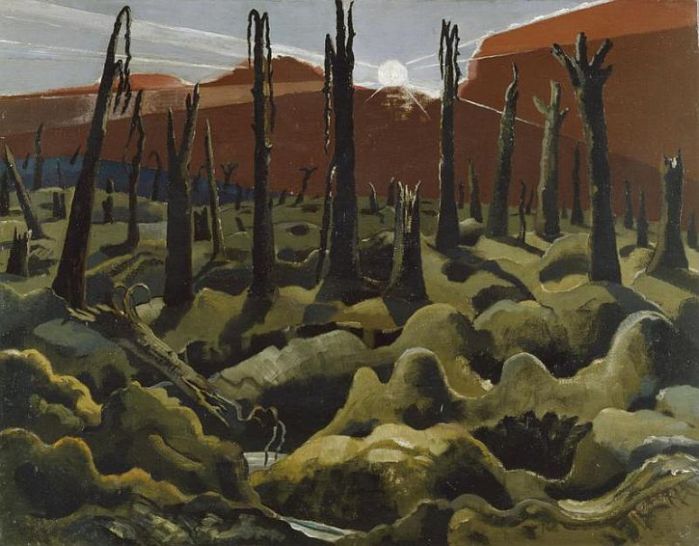

Paul Nash, ‘We Are Making a New World’, 1918

Nash arrived at the Ypres Salient at an unusually quiet time (though nowhere in the trenches could be considered safe or particularly quiet). At twilight, as he patrolled the trenches, Nash had time to absorb the strange beauty of the battlefront landscape. He was impressed by the powerful continuity of nature in the midst of the bombed and battered countryside.In a letter home he wrote:

Twilight quivers above, shrinking into night, and a perfect crescent moon sits uncannily below pale stars. As the dark gathers, the horizon brightens and again vanishes as the Very lights rise and fall, shedding their weird greenish glare over the land. … At intervals we send up Very lights, and the ghastly face of No Man’s Land leaps up in the garish light , then, as the rocket falls, the great shadows flow back, shutting it into darkness again. … Maybe you can feel something of the weird beauty from this little letter.

Paul Nash, ‘Spring in the Trenches, Ridge Wood’, 1917

Nash, like many other artists, writers and poets on the Western Front found himself, as Gough observes, ‘wrestling with the cruel irony that the destruction and depravity all around him was actually feeding his imagination. His early drawings from this period use a bright, even colourful, palette, depicting natural scenes which appeared undisturbed by war. In a letter home he wrote:

Everywhere are old farms, rambling and untidy, some of course ruined and deserted, all have red or yellow or green roofs and on a sunny day they look fine. The willows are orange, the poplars carmine with buds, the streams gleam brightest blue and flights of pigeons go wheeling about the field. Mixed up with all this normal beauty of nature you see the strange beauty of war. Trudging along the road you become gradually aware of a humming in the air, a sound rising and falling in the wind. You look up and after a second’s search you can see a gleaming shaft in the blue like a burnished silver dart, another and then another…

Paul Nash, ‘Existence’, 1917

Nash’s sensitivity to the incongruity of spring unfolding amid the destruction is very similar to words that the poet Edward Thomas put down in his diary that same spring while stationed not far away, outside Arras:

Linnets and chaffinches sing in waste trenched ground with trees and water tanks between us and Arras. Magpies over No Man’s Land in pairs.

On another day Thomas records watching a French farmer ploughing a field just behind the lines, driving his team right up to a crest that was in full view of the German gunners at Beaurains, before turning slowly around. It’s impossible not to be reminded of the exquisite poem Thomas had written just before leaving for the front, ‘As the Team’s Head Brass’:

As the team’s head-brass flashed out on the turn

The lovers disappeared into the wood.

I sat among the boughs of the fallen elm

That strewed the angle of the fallow, and

Watched the plough narrowing a yellow square

Of charlock. Every time the horses turned

Instead of treading me down, the ploughman leaned

Upon the handles to say or ask a word,

About the weather, next about the war.

Scraping the share he faced towards the wood,

And screwed along the furrow till the brass flashed

Once more.

The blizzard felled the elm whose crest

I sat in, by a woodpecker’s round hole,

The ploughman said. ‘When will they take it away? ‘

‘When the war’s over.’ So the talk began –

One minute and an interval of ten,

A minute more and the same interval.

‘Have you been out? ‘ ‘No.’ ‘And don’t want to, perhaps? ‘

‘If I could only come back again, I should.

I could spare an arm, I shouldn’t want to lose

A leg. If I should lose my head, why, so,

I should want nothing more…Have many gone

From here? ‘ ‘Yes.’ ‘Many lost? ‘ ‘Yes, a good few.

Only two teams work on the farm this year.

One of my mates is dead. The second day

In France they killed him. It was back in March,

The very night of the blizzard, too. Now if

He had stayed here we should have moved the tree.’

‘And I should not have sat here. Everything

Would have been different. For it would have been

Another world.’ ‘Ay, and a better, though

If we could see all all might seem good.’ Then

The lovers came out of the wood again:

The horses started and for the last time

I watched the clods crumble and topple over

After the ploughshare and the stumbling team.

Paul Nash, ‘Ruined Country’, 1917

Imagine a wide landscape flat and scantily wooded and what trees remain blasted and torn, naked and scarred and riddled. The ground for miles around furrowed into trenches, pitted with yawning holes in which the water lies still and cold or heaped with mounds of earth, tangles of rusty wire, tin plates, stakes, sandbags and all the refuse of war… In the midst of this strange country… men are living in their narrow ditches.

Nash wrote those words on Good Friday, 6 April 1917. Fifty miles to the south, Edward Thomas noted ‘infantry with yellow patches behind marching soaked up to line’. The Battle of Arras was about to begin, and on Easter Monday, as the British infantry attack began, Thomas was knocked down by the blast from an enemy shell, and killed instantly. ‘Thomas is dead…’ Nash wrote some time later after hearing the news. ‘I brood on it dully.’

Paul Nash, ‘Indians in Belgium’, 1917

After only three months at the front Nash was injured after falling into a trench and invalided back to England. Convalescing at home a week later, Nash learned that his division had been virtually annihilated – with most of his fellow-officers killed – in an attack on the infamous Hill 60 that presaged the Messines Ridge offensive.

While on leave, Nash exhibited some war drawings in London. The work was noticed by the War Artists Advisory Committee and so, when he returned to France later that year, it was as an official war artist. He arrived in the aftermath of the Battle of Passchendaele, ‘the blindest slaughter of a blind war’ in the words of AJP Taylor, and now his eyes were truly opened to the horrors of war. In his notes he wrote:

I realise no one in England knows what the scene of the war is like. They cannot imagine the daily and nightly background of the fighter. If I can, I will show them….

Paul Gough’s account draws heavily upon Nash’s writing, revealing it to be amongst the most vivid to come out of the war. In late 1917, for instance, he wrote to his wife:

I have just returned, last night, from a visit to Brigade Headquarters up the line and I shall not forget it as long as I live. I have seen the most frightful nightmare of a country more conceived by Dante or Poe than by nature, unspeakable, utterly indescribable. In the fifteen drawings I have made I may give you some idea of its horror, but only being in it and of it can ever make you sensible of its dreadful nature and of what our men in France have to face. We all have a vague notion of the terrors of a battle, and can conjure up with the aid of some of the more inspired war correspondents and the pictures in the Daily Mirror some vision of battlefield; but no pen or drawing can convey this country – the normal setting of the battles taking place, day and night, month after month. Evil and the incarnate fiend alone can be master of this war, no glimmer of God’s hand is seen anywhere. Sunset and sunrise are blasphemous, they are mockeries to man, only the black rain out of the bruised and swollen clouds all through the bitter black of night is fit atmosphere in such a land. The rain drives on, the stinking mud becomes more evilly yellow, the shell holes fill up with green-white water, the roads and tracks are covered in inches of slime, the black dying trees ooze and sweat and the shells never cease. They alone plunge overhead, tearing away the rotting tree stumps, breaking the plank roads, striking down horses and mules, annihilating, maiming, maddening, they plunge into the grave that is this land; one huge grave, and cast up on it the poor dead. It is unspeakable, godless, hopeless. I am no longer an artist interested and curious, I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate, will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls.

As the messenger, Paul Nash created some of the most devastating landscapes of war ever painted, his outrage at the waste of life was expressed through his depiction of the violation of nature in landscapes that were both visionary and terrifyingly realistic. In a perceptive opening to his chapter on Nash, Paul Gough observes that ‘of all British artists of the last century, Paul Nash is perhaps the one most readily associated with the sanctity and loveliness of trees’. As a visionary painter, Nash sensed the metaphysical power of trees – how they ‘linked the underworld, the earth’s surface and the skies’. Nash was sensitive, not only to the human carnage he witnessed, but also to the devastation of the verdant plains of Flanders, Artois and Picardy, where trees had offered ‘vantage and protection, raw materials and nourishment’, in thick forests and neat copses.

Once cherished as a place of refuge and shade, copses or small woods now became death traps, infamous killing grounds. Trees were cleared for safety by artillery shelling or felled for military use. Nash saw all this, writes Gough:

He was aghast at the sight of splintered copses and dismembered trees, seeing in their shattered limbs an equivalent for the human carnage that lay all around or even hung in shreds from the eviscerated treetops. In so many of his war pictures, the trees remain inert and gaunt, failing to respond to the shafts of sunlight; their branches dangle lifelessly ‘like melancholy tresses of hair’, mourning the death of the world and its values that Nash held so dear’.

Myfanwy Piper later observed that:

The drawings he made then, of shorn trees in ruined and flooded landscapes, were the works that made Nash’s reputation. They were shown at the Leicester Galleries in 1918 together with his first efforts at oil painting, in which he was self-taught and quickly successful, though his drawings made in the field had more immediate public impact. His poetic imagination, instead of being crushed by the terrible circumstances of war, had expanded to produce terrible images – terrible because of their combination of detached, almost abstract, appreciation and their truth to appearance.

Paul Nash, ‘After the Battle’, 1918

Paul Nash, ‘Rain: Lake Zillebeke’, 1917

Nash’s anger, writes Gough, was converted into a suite of taut drawings, ‘each one scooped out of the muddy places, barren ridge lines, and filthy puddles of the Salient’. In works such as Rain: Lake Zillebeke or After the Battle, Nash ‘created a new calligraphy of war’:

His drawings are scored and scratched with uncompromising diagonals, the incessant rain is engraved in stabbing lines across the surface, the ashen wastes of the battlefield are dense with impenetrable strokes of his pen. […] Nash had created a distinctive vision of war, one that brought new insights into the way that artists could depict the absences, the emptiness, the abraded surfaces, and the defiled hollows that were the essence of the Western Front.

Paul Nash, Poster for The Void of War exhibition, May 1918

In May 1918 The Void of War, an exhibition of pictures by Paul Nash, opened in London. The most acclaimed work in the exhibition was the heavily ironic We Are Making a New World (above), ‘a brazenly symbolic canvas developed from a drawing of a sunrise at Inverness Copse, a derelict woodland deep in the Ypres Salient’. The painting has become one of the most memorable images of the First World War, the title mocking the ambitions of the war, as the sun rises on a scene of the total desolation.

Paul Nash, ‘Sunrise Inverness Copse’, 1918

Paul Nash, ‘Void’, 1918

In these key drawings and paintings, Nash was beginning to work out a means of portraying the battlefield in concrete terms. His use of colour had become more ambitious, and in Void, one of the most powerful paintings exhibited in London, acidic colours depict the total devastation of war in a shocking, hellish scene that, far from commemorating valour, rather reveals the desolation, destruction, and terror of war.

Paul Nash, ‘The Ypres Salient at Night’, 1918

The Ypres Salient at Night shows three soldiers on the fire step of a trench surprised by a brilliant star shell lighting up the view over the battlefield. The painting shows us a fragmented world of chaos, where the demarcation of day and night, order and disorder, no longer exists as bombing continues throughout the night.

Paul Nash, ‘The Mule Track’, 1918

In The Mule Track, Nash presents the viewer with another terrifying scene. Amidst the chaos of a heavy bombardment the small figures of a mule train are trying to cross the battlefield. They are reduced to defenceless puppets at the mercy of terrible forces. The animals rear and panic at nearby explosions, as the water in the flooded trenches wells up like geysers and rubble is thrown high into a sky obscured by large clouds of yellow and grey smoke.

Paul Nash, ‘Men Marching at Night’, 1918

In a very fine drawing from this period, Nash shows a view along a straight road lined with tall trees that loom over a column of British soldiers marching down the road. The rain drives across the composition from the left, and the soldiers huddle beneath cloaks whilst marching. There are echoes in this work of CRW Nevinson’s handling of a similar subject matter in his war work, Column on the March from 1914 (see my earlier post). Nash certainly admired Nevinson, and recorded in a letter in July 1917 that they had just met.

Paul Nash, ‘Wire’, 1918

Wire is a poignant watercolour of a desolate landscape, described by the artist and writer Deanna Petherbridge in these terms:

Great bomb craters filled with sullen waters, possibly concealing rotten corpses; the pitiful paths up and down dunes that speak of some hidden human presence; the pall of smoke partly filling the sky; the imagined stench. We assume that it is winter from the degraded palette, but it could just be the winter of the soul – war allows no other season than that of desolation. What makes this painful watercolour so memorable is the blasted tree, a great ripped phallic symbol enmeshed with barbed wire. There is a long tradition in Western landscape art of decaying tree stumps as symbols of destroyed civilisations. In sixteenth and seventeenth-century landscapes such signs of decay signify renewal, but in this modern work about the horrors of war, rebirth has been suspended.

Paul Nash, ‘The Menin Road’, 1919

A month before the London exhibition opened, Nash had been commissioned by the Ministry of Information to make a large oil painting – originally to have been called A Flanders Battlefield – that was to feature in the planned Hall of Remembrance, alongside paintings by William Orpen and John Singer Sargent. The intention was that both the art and the setting would celebrate national ideals of heroism and sacrifice. However, the Hall of Remembrance was never built and the artists’ work ended up with the Imperial War Museum.

Nash worked on the painting from June 1918 to February 1919, choosing as his subject the main road between Ypres and Menin. He would remember it as a road in name only, torn up by shellfire and deserted in daylight. It was one of the most dangerous parts of the Western Front with notorious sites of battle – Sanctuary Wood, Hooge Crater, Inverness Copse and Hellfire Corner – strung out along the road. (As an inscription for the painting, Nash suggested: ‘The picture shows a tract of country near Gheluvelt village in the sinister district of ‘Tower Hamlets’, perhaps the most dreaded and disastrous locality of any area in any of the theatres of War.’)

Gough discusses the ‘highly sophisticated image’ that resulted from months of work in a temporary studio at Chalfont St Giles shared with his brother in these terms:

By subtly dividing the canvas into three broad bands – a deep foreground of water-filled craters, the lateral axis of the road in the middle band, and the shattered landscape in the distance – [Nash] drew out the different directional properties in each of the three zones without losing either the phantasmagoric properties of the emptied landscape, nor the nullity of a place that had been relentlessly stripped of its former identity.

As so often in Nash’s war work, the foreground is crammed with insurmountable obstacles – pools of water that cannot easily be crossed, pyramidal blocks that bar the way into the interior space of the painting, piles of debris that clutter the ground plane.

The viewer, writes Gough, seeks a way through the obstructions ‘into the distance where the ‘Promised Land’ of the horizon is unreachable, locked in some unimaginable future’.

Nash considered The Menin Road to be the best thing he had ever done. ‘He was right’, argues Gough, concluding that Nash had emerged from the war as by far the most important and original young artist in Britain (he was just 28 at the war’s end). Ahead, wrote Nash in 1919, lay the ‘struggles of a war artist without a war’. He could not have known then that in another 20 years he would, once again, be appointed an official war artist.

See also

- Edward Thomas: Now All Roads Lead to France

- A Terrible Beauty: British artists in the First World War

- Art of the First World War: multilingual website produced on 80th anniversary of the end of the War

- Why paint war? British and Belgian artists in World War One: article by Paul Gough (British Library)

- Brushed aside by the chaos of conflict: A Crisis of Brilliance at the Dulwich Picture Gallery (Independent)

- Paul Nash: Modern Artist, Ancient Landscape: Tate Liverpool, 2003

- The Art of War

Reblogged this on Charles Kenwright, openmindimages and commented:

Continuing on from his first post about WW1 artists, Gerry Cordon now writes about Paul Nash.

Great post. Nash had the ability to tell it like it was though his art. He manages to capture something of the atmosphere; which must have been disturbing afterwards, for those who had actually “been there.”

His pictures tell a true story in a raw and yet poetic style. There is real emotion and violence, with out the patronizing sentiment. I have felt for years he deserved a higher status than he seems to often have. Andy.

My research often leads to your blogs. Another gem. Thank you.

Thanks, Susan, comments like yours make blogging worthwhile!

Wow, this is a great post, Gerry. I’m a big fan of Wilfred Owen war poetry, myself, and I didn’t really know Paul Nash’s work.

I went to the Paul Nash show at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London. Brooding intense work!http://www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/about/exhibitions-archive/modern-british/2010-paul-nash/ But your blog captures some of my favorites. Thankyou.

This is a great article, very informative. Thank you for writing it!

This is an extraordinary piece. You’ve written it beautifully thank you. I’d heard of Nash’s war paintings but never bothered to look them up, what a mistake, they are more striking and moving than I could have imagined.

Thanks for your comment, Megan – and for bringing me back to a three-year old post on the day when, 100 years ago, the hell of the battle of Passchendaele began.http://bit.ly/2hfu0di