For days after Christmas I didn’t leave the sofa, enthralled by The Beatles Tune In, the first of three volumes in which Mark Lewisohn intends to tell the definitive story of the Beatles. It’s a grand book in every sense of the word: this volume clocks in at close on a thousand pages, ending as the group travel to London to record their first single ‘Love Me Do’; it’s also meticulously-researched and written with passion, authority and elegance. This is not your average pop hagiography, but is also an informed and insightful social history of Liverpool and the emergent youth culture of the 1950s. After this, all future accounts of the lives of the Beatles will be redundant. Continue reading “The Beatles Tune In: Mark Lewisohn’s definitive account of the Liverpool years”

Tag: Brian Epstein

Cilla and sixties Liverpool: recreation of a mythical city

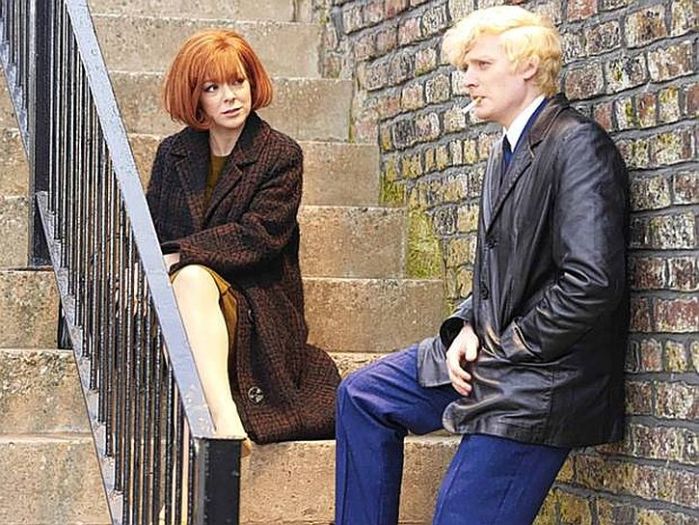

Sheridan Smith in ‘Cilla’

Along with seven million other viewers, watching ITV’s Cilla I was lost. Not expecting much after previous lacklustre depictions of Liverpool during the Merseybeat boom, I was transported by Sheriden Smith’s scintillating performance in the lead role of the teenage Cilla Black, by the convincing script and uniformly sound acting. The drama recreated sixties Liverpool with realistic locations and accents, but also captured the essence of a mythical city from which exploded all the promise and excitement of the Mersey sound, heralding a bright new future of youthful liberation. Transfixed by it all from a distance in 1963, from that time on I was drawn inexorably to a city that seemed aglow with opportunities, and in which I settled four years later.

In three episodes, Cilla written by Jeff Pope and directed by Paul Whittington, lovingly recreated Liverpool in the early sixties, confining itself to the three years that saw the 17 year-old typist Priscilla White, denizen of beat clubs like the Iron Door and The Cavern, transformed into the 20 year-old Cilla Black after being taken on by Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein, recording a series of chart-topping hits beginning with ‘Anyone Who Had a Heart’ to become Britain’s biggest female pop star of the decade.

I was gripped from the first episode which evoked all the excitement of 1960s Liverpool, recreating an exuberant music scene that thrived in countless clubs like The Cavern in which over three hundred groups such as The Big Three, Rory Storm and the Hurricanes and Kingsize Taylor and The Dominoes (and The Beatles, of course) belted out versions of American pop, soul rhythm and blues and soul numbers learned from singles brought over from New York by the ‘Cunard Yanks’, scouse stewards who worked on Cunard transatlantic liners sailing from the port. This was music the rest of Britain, reliant on the BBC Light Programme’s bland playlist, never got to hear.

This was a city in which young lads bought guitars, formed groups, and learned to play the music they heard on the singles brought across the Atlantic by the Cunard crews – raunchy numbers by names that would not become familiar to the rest of the country until years later – rock’n’rollers like Little Richard and Chuck Berry, blues men like Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters, and early Motown artists such as The Miracles, The Marvelettes and Barrett Strong. Rocking along in the audiences were teenage girls like Beryl Marsden and Cilla White – girls who knew the songs inside out and soon were on stage with the lads, belting out numbers with abandon. Everyone – performers and audience alike – found in these lunchtime or evening sessions a release from the drudgery of their daytime work in factory or office.

The Clayton Squares at The Cavern, early sixties (note the seated audience)

Growing up in a mildly repressive and fairly joyless household in rural Cheshire, the explosion of the Mersey sound and the arrival of the Beatles bearing aloft the banners of youth and freedom, and thumbing their nose at everything staid or square meant Liverpool became for me a golden city, a beacon of liberation.

The city I found when I arrived in 1967 was, of course, very different from this mythical image. Black, soot-encrusted buildings, endless streets of run-down, red-brick terraces; a port city where already the docks were dying and waterside warehouses crumbled. The Pier Head was a far cry from the image that Gerry Marsden’s anthem had conjured in my mind: a wind-whipped wasteland where crowds huddled on the land-stage, waiting for the Birkenhead ferry.

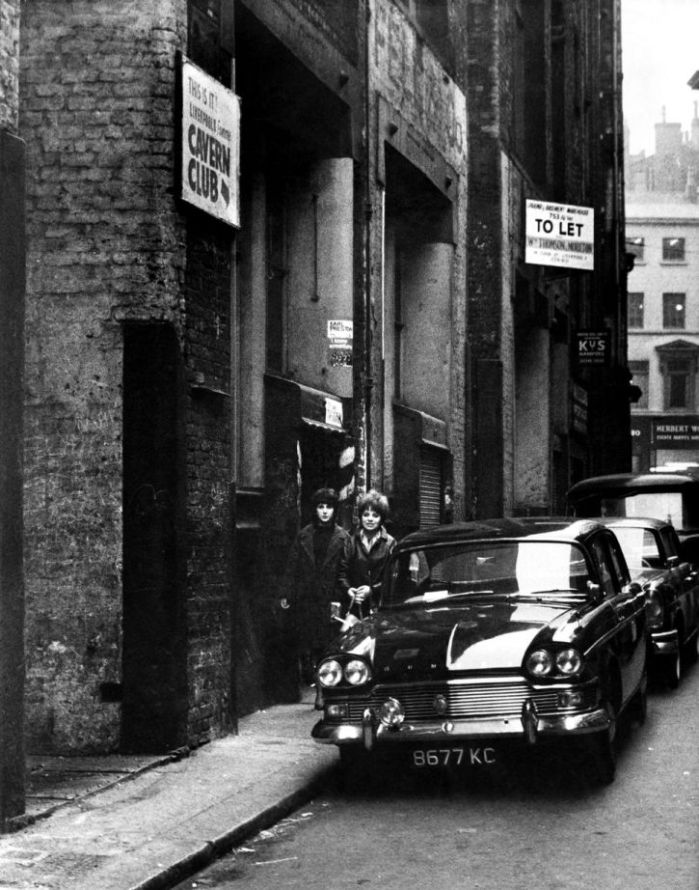

The Cavern Club in Mathew Street, December 1963

Yet – it was a vibrant place, even if the beat groups had mostly gone and The Cavern and the rest of the club scene was past its heyday. I found the Liverpool Scene and their weekly gatherings at O’Connor’s Tavern, poetry and drama at the Everyman. I lived in Liverpool 8, the elegant frontages of its Georgian streets disguising the landlord neglect and disrepair that you found inside. I relished the many colours of Granby Street, the jostling crowds at Paddy’s Market, and found amidst the poverty and dereliction a place of great good humour, a teeming mix of identities, laughter and conversation on the buses and in the shops, jokes and singing in the pubs, a pride in the city’s sense of difference – and the football. Two teams, two cathedrals (one unfinished, one an angular modernist masterpiece): in pub singalongs, when it came to ‘In My Liverpool Home’ (as it always did), some would sing ‘If you want a cathedral we’ve got one to spare’, while others, fewer in number back then, marked their rejection of the city’s religious divide by singing ‘we’ve got two to spare’.

Cilla Black, Billy J Kramer & Dakotas, The Beatles, and The Searchers in an all-Merseyside special edition of ‘Thank Your Lucky Stars’, 1963

In the first episode, Cilla works by day in a typing pool but at night checks coats at The Cavern and haunts other clubs, angling for a spot on stage. The Beatles have already been spotted by Brian Epstein, and Ringo (who has already replaced Pete Best as the band’s drummer at Epstein’s behest) puts Cilla in touch with him. The Beatles angle is not overplayed – we only see glimpses of them on stage, or as part of Cilla’s social circle. Cilla dreams of being taken on by Epstein, but it seems that Beryl Marsden has beaten her to it. However, local lad Bobby Willis (played by Aneurin Barnard) is drawn to Cilla, and offers to be her manager. His first attempt at negotiating terms leads to Cilla taking a pay cut for her appearances.

Sheridan Smith filming ‘Cilla’ in Liverpool (photo: ITV Granada)

There’s a lot of convincing location shooting (aided by some effective CGI). Cilla’s family lived above a barber’s on Scotland Road with no separate entrance of their own (her mother always hated that, and would insist that visitors came round the back way). The working class streets around Scottie Road are long gone, demolished in the massive slum clearances of the late sixties that saw people rehoused in the Everton tower blocks or out in Kirkby – so most of the filming was done in the south end. Cilla’s home was recreated on Duke Street, while for Ringo’s home there were several shots of the lovely terrace that runs the length of Yates Street, off Mill Street, with its raised landing. (Incidentally, the street – one of three built to house workers at the large flour mill that still operates opposite the houses – was saved from destruction by the residents themselves, who formed themselves into the Corn and Yates Street Housing Co-op).

Cilla Black’s home above the barber’s on Scotland Road

The growing romantic relationship between Cilla and Bobby Willis (who did, finally become her manager after Epstein’s death – and her husband, until his death in 1999) is presented with just the slightest touch of schmaltz, and a great deal of humour. Example: after Cilla’s made her first record and her docker dad Mr White has reluctantly agreed her name-change to Black, his workmates tell him he’s ‘a failed minstrel . . . doesn’t know if he’s Black or White’. (Remember the Black and White Minstrel Show? Different times, for sure.)

And here was something I’d nearly forgotten – the religious divisions in the city that meant a Catholic girl like Cilla wasn’t meant to be knocking around with a Protestant like Bobby.

The origins of Liverpool’s religious divide lay in its sizeable population of Irish origin, the result of large-scale immigration in the 19th century, which made it a city divided, like Glasgow, with Catholics and Protestants sticking rigidly to their communities and frowning on intermarriage. There were Liverpool Protestant Party councillors until 1973, and Irish Nationalist councillors had represented the Scottie Road area until after the Second World War (while the MP for Scotland Road was, until 1929, an Irish Nationalist). I remember when I arrived in the city in 1967, being taken aback by the annual Orange Lodge marches and the ‘No Popery’ and ‘LOL’ slogans painted on walls along Netherfield Road.

Cilla came from Catholic Scotland Road, where her mother ran a market stall, while her boyfriend Bobby Willis was a Proddy. This delicate issue was treated with typical scouse humour in the drama: in one scene Cilla’s dad takes Bobby to one side for a serious talk:

Cilla’s Dad: ‘I had a word with her mother and I broke it to her that you’re not a Catholic.’

Bobby: ‘Look, Mr White, I’ve had it up to ‘ere with religion. Proddy? Catholic? What does it matter? I care a lot about your daughter: I’m gonna look after her, and I’m gonna respect her, and that’s the best I can do.’

Cilla’s Dad stares at him: ‘I was just gonna say, she’s accepted the situation. But I’d be grateful if you didn’t mention your persuasion to any of her aunties. And there’s just one more thing. Tell the wife you support Everton and not Liverpool.’

Sheriden Smith and Aneurin Barnard as Bobby Willis

Bobby was also a singer and songwriter: he did backing vocals on her chart topping hits and wrote the B-side (‘Shy of Love’) to her first single, Paul McCartney’s ‘Love of the Loved’. His relationship with Cilla strengthened in the second episode, which focused entirely on the few months between Cilla’s disastrous first audition for Epstein to her eventual signing with him, and having a No 1 hit with ‘Anyone Who Had a Heart’. This episode was beautifully composed – a masterpiece that could stand alone – opening with Cilla seeming to have lost her one chance of stardom and ending with her triumphant recording of ‘Anyone Who Had a Heart’

Cilla had been introduced to Epstein by John Lennon, who persuaded him to audition her. Her first audition (the final scene of episode 2) was a failure, partly because of nerves, and partly the fault of the Beatles. She chose to do ‘Summertime’, a song she adored and had sung with the Big Three, but had not rehearsed with the Beatles, who played it in the wrong key.

But she gets a second chance with Epstein, travelling to Abbey Road studios in London for her first recording session with Beatles producer George Martin. She sings McCartney’s ‘Love of the Loved’ and halfway through the song Martin halts the recording and leaves the booth to have a quiet word with Cilla: could she try not to pronounce ‘there’ as ‘thur’? They do another take, but this time she’s singing ‘care’ as ‘cur’. When released the single failed to make the top 30.

But for her second single, Martin offers her the chance of a lifetime – a song already released in the States by Dionne Warwick, written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, and one that he had in mind for Shirley Bassey. In the drama he passes the Warwick single over to Cilla – she already knows it. It’s one of those Cunard Yank discs that any scouse music fan worth their salt would know.

Bobby is not impressed: it’s a ballad for Christ’s sake! He predicts she’ll lose all credibility with her Liverpool fans if she doesn’t record something that’s more rock’n’roll. But Cilla senses the potential in the song and the recording begins. In a brilliant piece of direction, at this point we only see but do not hear her performance. Bobby has stormed out of the recording studio, but comes back to watch as she sings through the window of the sound-proof studio door.

Cilla Black in December 1963

The couple return to Liverpool to wait for the charts. Taking the call from Epstein in the phone box across the road, they learn its gone to number one. It’s only then that director Paul Whittington gives us the recording studio performance of the song with sound, closing the episode on a triumphant high. Indeed, Sheriden Smith’s climactic performance of ‘Anyone Who Had A Heart’, might just have been even better than Cilla’s.

Trailer

Sheriden Smith’s performance of ‘Anyone Who Had a Heart’

After the memorable closing scene of episode two, I went to YouTube to compare Cilla Black’s version with Dionne Warwick’s. To my mind, there’s no contest. In her rendition Warwick sounds younger and less experienced, even though she has three years on Cilla. In her version, Cilla Black attacks the song with a passion and maturity that belies her twenty years. But decide for yourself:

Cilla Black’s ‘Anyone Who Had a Heart’

Dionne Warwick’s ‘Anyone Who Had a Heart’

In under three hours of enjoyable television, Cilla conjured up this ‘wondrous place’ that is Liverpool (recalling the title of a song by Billy Fury, the late fifties rock’n’roller from the Dingle whose statue can be found at the Pier Head, and which Paul du Noyer took as the title for his book, the best that has been written about Liverpool and the music it makes). Specifically, Cilla successfully evoked the mythical Liverpool of the Merseybeat boom years – a mythical city of The Beatles et al that drew me and many others to it, including, in 1965, Allen Ginsberg, who made a special detour to see the place which he famously announced was ‘at the present moment the centre of the consciousness of the human universe’.

Adrian Henri later claimed that Ginsberg’s famous statement referred to ‘the cataclysmic effect of the Beatles and Merseybeat in general, while the visual arts (and poetry) benefited from the sheer headiness, the excitement of the time, as well as the attention generated by the music’. George Melly observed that ‘the ‘Pool’ feels itself closer to Dublin, New York, even Buenos Aires than it does to London…It’s very aware of its own myth and eager to project it’.

I’ll end with a passage or two from Paul du Noyer’s, Wondrous Place, which begins with a remark made by Herman Melville after visiting Liverpool in 1839 :

In the evening, especially when the sailors are gathered in great numbers, these streets present a most singular spectacle, the entire population of the vicinity being seemingly turned into them. Hand-organs, fiddles and cymbals, plied by strolling musicians, mix with the songs of the seamen, the babble of women and children and the whining of beggars. From the various boarding houses… proceeds the noise of revelry and dancing.

Du Noyer continues:

Liverpool is more than a place where music happens. Liverpool is a reason why music happens. When the author of Moby Dick sailed to Liverpool from New York he found a town obsessed by entertainment: there was a physical appetite for life and he was shocked by its ferocity. […] What is it about Liverpool? Is it something in the water? Why does so much music come from here? Why do they talk like that? Why are Scousers always up to something? […]

Liverpool now is the same as it always was: a turbulent, teeming city, alive with vice and excitement. Old Melville knew it as a seaport above all: young Moby might not have been aware of any river, but he was witnessing its legacy all the same. Life at sea is hard. When sailors are ashore their preoccupation is with entertainment. The port of Liverpool was made to supply Jack’s every need, whether it be for tarts or tarpaulin. Naturally the town was prepared to offer entertainment too. And that readiness became a civic tradition of the town, an acquired characteristic of its people that shaped their very nature. That’s how Liverpool became the cradle of British pop. It was always a town where entertainment was actively sought. The appetite was sharper and the demand was, well, more demanding. […]

Deep in the heart of the place,’ says a local writer Ronnie Hughes, ‘a constant pop song keeps getting written, which lifts its spirits when sometimes it seems nothing else can. This is not a place that’s given up. It’s a proud, boastful Celtic city where the lads dream big and talk big and keep writing a big, tuney, hopeful song that could only come from Liverpool.’

Paul du Noyer concludes his book with this statement:

I rather suspect there are more wonders to come from this wondrous place.

Footnote:

Admirably succinct praise for Cilla from Martin Colyer’s Five Things blog .

You Gorra Luv It!

Sheridan Smith is Cilla Black. Yet another terrific central portrayal by a British actress, here in a tale that could fall flat – like biopics often do – but is great for these reasons: a) The art direction, set dressing and period clothes are never lingered on in that “We’ve spent a bundle on this, we have to show it off” way. They do the job incidentally, while being great to look at. b) There’s a rich seam of humour running through the script, a lightness of touch that tells the story whilst avoiding literalness. c) The music feels live (Smith sang live throughout the whole of the first episode). She also sings all the studio takes and the cute build-up to hearing her finally sing “Anyone Who Had A Heart” – held to the end of part two, even though we see her recording it much earlier, ends the episode brilliantly. The session, overseen by George Martin, has a fabulously-cast bunch of Abbey Road sessioneers with cardigans, suits, glasses and thinning hair.

See also

The Beatles make history in Port Sunlight

A Historic Date In Music: August 18, 1962, Hulme Hall, Port Sunlight, Merseyside

Re-posted from sixstr stories, an excellent blog that records important dates in musical history.

This one was especially significant for a whole generation, now old and losing their hair, and unable to believe that it really was 50 years ago that the Beatles in their final form played their first gig together in a village hall on the Wirral. On 4 September 1962, the Beatles in their new line-up recorded a ‘Love Me Do’ at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios. Released on 5 October 1962, the single reached number 17 in the UK pop charts, and a cultural storm was coming.

In 1959, he was the drummer with Rory Storm & The Hurricanes, the biggest of all the groups in Liverpool, England at that time.

But it wasn’t until October and November of 1960 when Rory Storm & The Hurricanes played alternating sets, seven nights a week, 6 to 8 1/2 hours a night, for eight weeks at a club called The Kaiserkeller in Hamburg, West Germany with another Liverpool group called The Beatles, that John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison really got to know Ringo Starr.

Back home, throughout 1961 and into 1962, John, Paul and George maintained their friendship with Ringo. He was the first one they’d call to fill in when drummer Pete Best couldn’t make an engagement. One such date was Monday, February 5, 1962. On this day, Ringo played two shows: lunchtime at The Cavern Club in Liverpool and an evening gig at the Kingsway Club in Southport.

In June of 1962, when The Beatles – John, Paul, George and Pete – auditioned for Parlophone Records, producer George Martin liked everything he heard, except Pete’s drumming. So, in early August, after much discussion, The Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein got the very difficult job of telling Pete that he was out. Two years and three days after he’d joined the band known originally as The Silver Beetles, Pete Best played his last performance with John, Paul and George at The Cavern Club on the evening of Wednesday, August 15, 1962.

Brian Epstein also got the job of calling Ringo Starr and offering him the position as full-time drummer for The Beatles.

When Brian called, Ringo was not only still playing for Rory Storm & The Hurricanes, he also had two other offers on the table. King Size Taylor & The Dominoes wanted him to play drums for them and Gerry & The Pacemakers wanted Ringo to be their bass guitar player (even though he had never played bass guitar!).

But Ringo loved playing with John, Paul and George and, as he later said, ”We were pals!” Ringo also knew that The Beatles were on the verge of getting a record deal with EMI and to him, ”a piece of plastic was like gold, was more than gold.”

And, The Beatles offered him the highest salary, £25 a week, to start.

So, shaving off his beard and getting his hair cut in the style worn by his new bandmates, Ringo said, “Yes.”

On Saturday, August 18, 1962, after a two-hour rehearsal, The Beatles – now officially John, Paul, George and Ringo – took the stage at Hulme Hall in Port Sunlight, Birkenhead, England as the headlining act of the Horticultural Society’s 17th annual dance.

Fifty years ago today.

Information for this post was gathered from The Complete Beatles Chronicle (1992) by Mark Lewisohn; The Beatles Anthology (2000) by The Beatles; and The Love You Make – An Insider’s Story of The Beatles (1983) by Peter Brown & Steven Gaines.