Like most during these last, terrible days I have been transfixed by the unfolding drama around the Charlie Hebdo massacre – horrified by events and fearful of what may be to come in Europe. This afternoon, however, the images of 1.5 million marching in Paris are breathtaking and heartening. And nearly a million more have joined rallies in towns across France.

A social worker on the Paris rally

And there have been more rallies in towns and cities across Europe, including Istanbul. In Cairo, members of the Egyptian journalist syndicate raised pens at a Charlie Hebdo gathering (though it should be pointed out that in Egypt 16 journalists, including three from al-Jazeera, are in jail. The al-Jazeera journalists have been held since December 2013 for ‘spreading false news’ and ‘membership of a terrorist organisation’.

I wanted to gather together some (fairly random) thoughts provoked by the events of the last few days, and the many articles I have been reading. First – though it ought not need emphasising, but does, what with talk here of ‘fifth columnists‘ and Rupert Murdoch tweeting that Muslims must be held responsible for the religion’s ‘growing jihadist cancer’ – two stories that Islamist terrorism has nothing whatever to do with being a Muslim.

Ahmed Merabet was the cycle-mounted police officer who was gunned down in cold blood by the two terrorists responsible for the massacre at Charlie Hebdo. He was a Muslim.

Ahmed Merabet

Today, his brother, Malek Merabet said:

My brother was Muslim and he was killed by two terrorists, by two false Muslims. Islam is a religion of peace and love. As far as my brother’s death is concerned it was a waste. He was very proud of the name Ahmed Merabet, proud to represent the police and of defending the values of the Republic – liberty, equality, fraternity.

Malek went on to appeal to French citizens that the country faced a battle against extremism, not against its Muslim citizens:

I address myself now to all the racists, Islamophobes and anti-semites. One must not confuse extremists with Muslims. Mad people have neither colour or religion. Don’t tar everybody with the same brush, don’t burn mosques – or synagogues. You are attacking people. It won’t bring our dead back and it won’t appease the families.

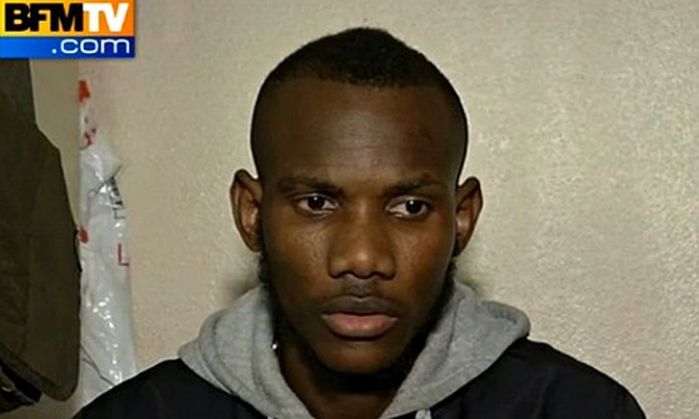

Lassana Bathily

Then there is Lassana Bathily, a young Muslim shop assistant originally from Mali, who worked at the Jewish supermarket attacked by the other gunman. He hid a group of shoppers, one with a baby, in a basement cold storage room at the Hyper Cacher supermarket to shield them from the gunman.

When they came running down I opened the door of the fridge. Several came in with me. I turned off the light and the fridge. When I turned off the cold, I put them in. I closed the door. I told them to stay calm and I said ‘you stay quiet there, I’m going back out’.

He managed to escape, but was detained in handcuffs by the police for more than an hour before they accepted that he was an employee. Now there are calls for his bravery to be recognised officially by the French nation.

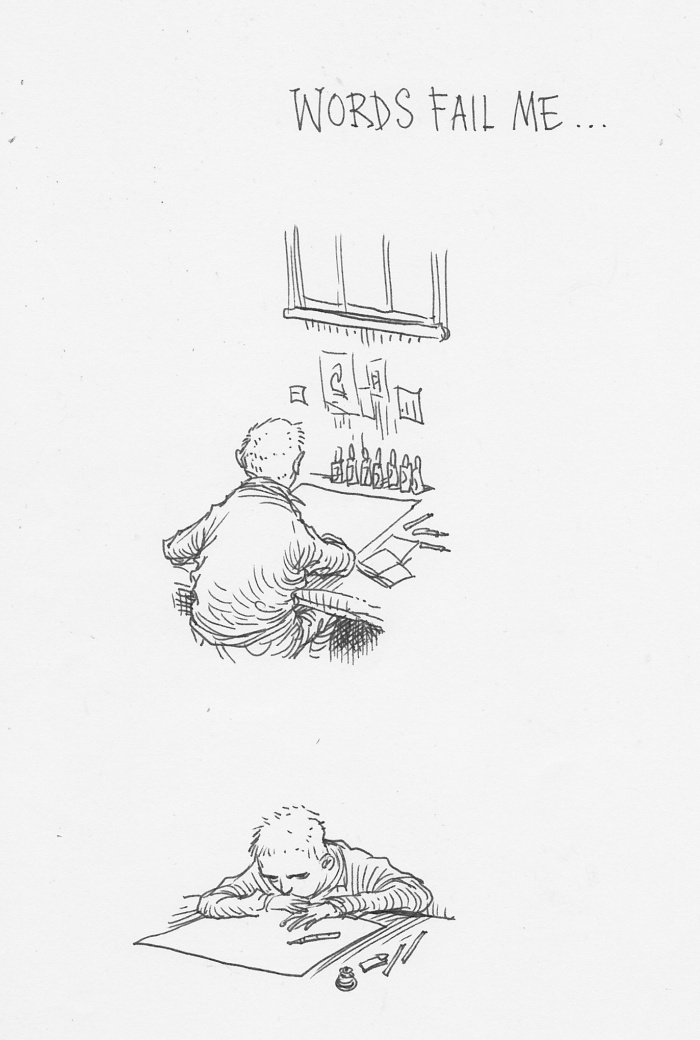

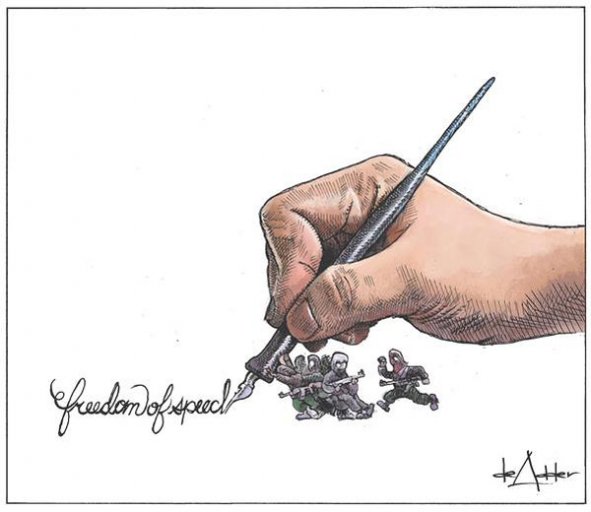

‘Words fail me’ by Observer cartoonist Chris Riddell

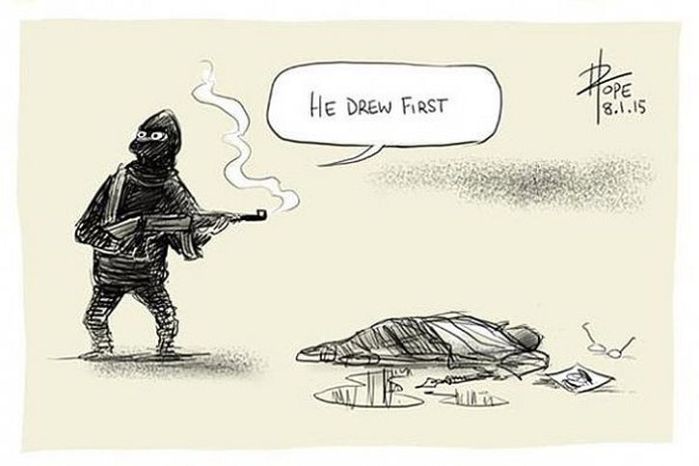

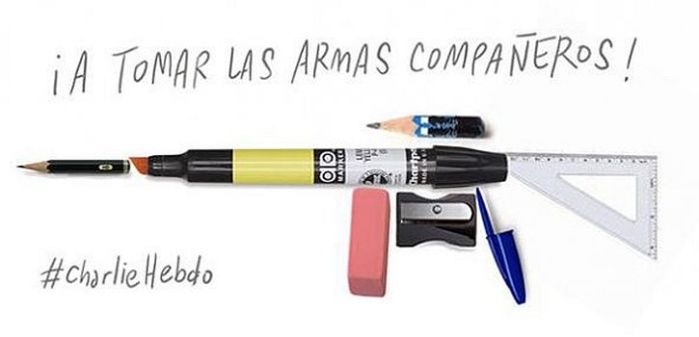

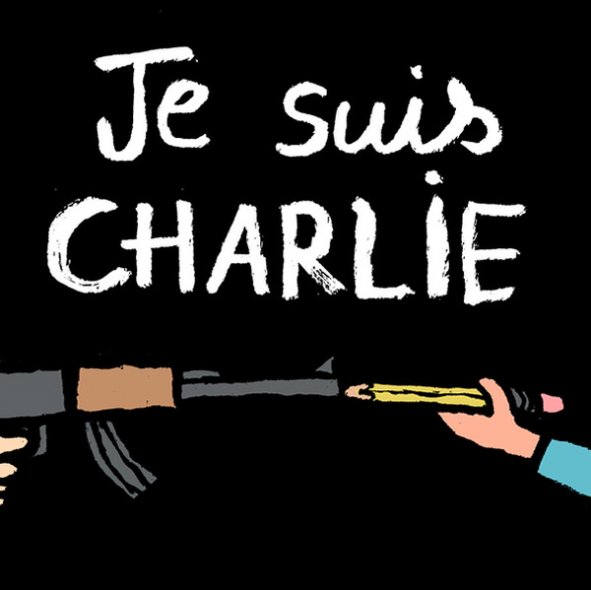

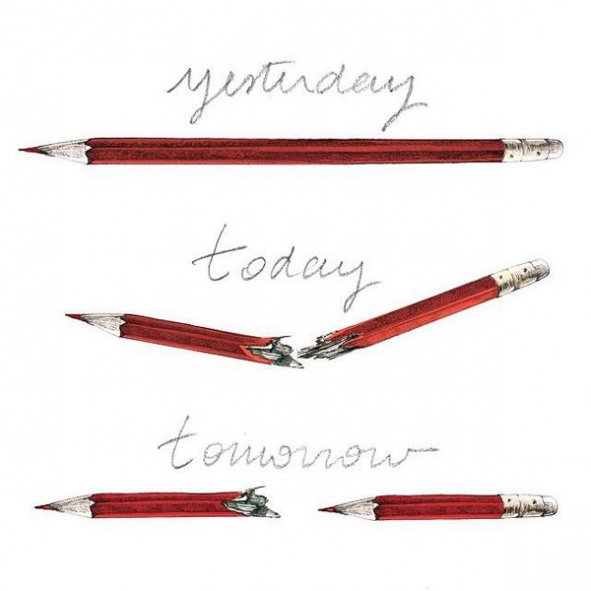

Of course, at the heart of this affair lies the question of freedom of expression, highlighting especially the power of the cartoon. More powerful than words, perhaps, since the ideas expressed in caricature can cross the boundaries of language and culture. Since the Charlie Hebdo attack there has been an outpouring of responses by cartoonists from across the world, and I have added a selection of those that have caught my attention at the end of this post. Today’s Observer featured one of the best – ‘Words fail me’ by Chris Riddell. The image above is the first of four images.

Also in the Observer, Ed Vulliamy has written a great piece about the importance of satirical caricature in French culture. He describes how Charlie Hebdo has deep roots in a tradition of graphic satire dating back to the 18th century, a tradition that was:

Released during a brief freedom of the press granted after the revolution of 1830 and brought to bloom by Honoré Daumier – with his savage depictions of the law at work – and Gustave Doré. It was not always a force of the left: a royalist cartoonist was guillotined by the revolutionaries in 1793 and antisemitic stereotypes were a characteristic of Vichy French cartoons during the Nazi occupation.

But cartoonists are what they are, instinctively if not always politically anarchist, and Charlie’s recent origins rest firmly in the uprising of May ’68, the zenith of “usines, universités, union” – factories, universities, united – as the slogan asserted on silkscreen prints by the Atelier Populaire, some of the greatest political art of the 20th century.

There is a deeper reason for this than just deserved mockery: in the pantheon of French republicanism, there is another word to add to the trinity of liberty, fraternity and equality: laïcité. “Secularity” doesn’t do the job of translation – laïcité describes France’s profound conviction and commitment that religion has no right or role to influence in society.

Even before the French Revolution, seditious prints circulated showing the clergy and nobility performing all sorts of demeaning acts. Pornographic images of Marie Antoinette were particularly popular. The subversive impact of cartoons was a major concern for the authorities into the 19th century. In 1829, the French interior minister complained:

Engravings or lithographs act immediately upon the imagination of the people, like a book which is read with the speed of light; if it wounds modesty or public decency, the damage is rapid and irremediable.

The following year, the French government outlawed attacks on ‘the royal authority’ and the King’s person.

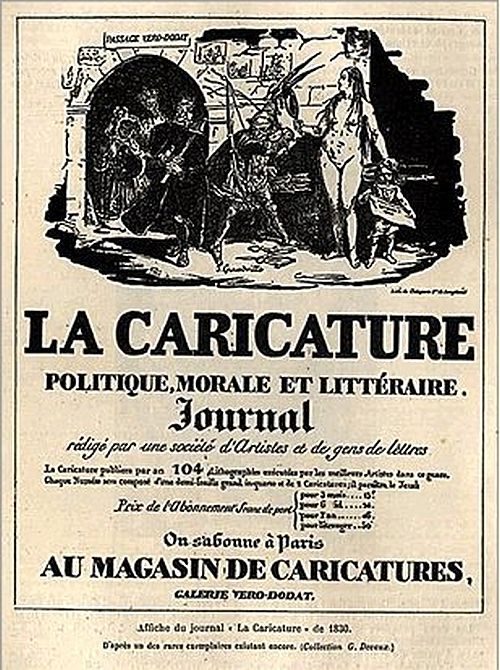

An 1830 issue of La Caricature

During the reign of Louis Philippe, Charles Philipon launched the comic journal, La Caricature, and Honoré Daumier, France’s greatest cartoonist, joined its staff. With a band of other leading caricaturists, Daumier began a campaign of satire, targeting the foibles of the bourgeoisie, the corruption of the law and the incompetence of a blundering government. In 1831, he drew an image of the King as a Rabelaisian giant, sitting on a commode and eating the food of the poor as he excretes wealth for the nobility. For that, Daumier was jailed, and in 1835 a law specifically targeting caricature was introduced, on the grounds that, said the government, ‘whereas a pamphlet is no more than a violation of opinion, a caricature amounts to an act of violence.’

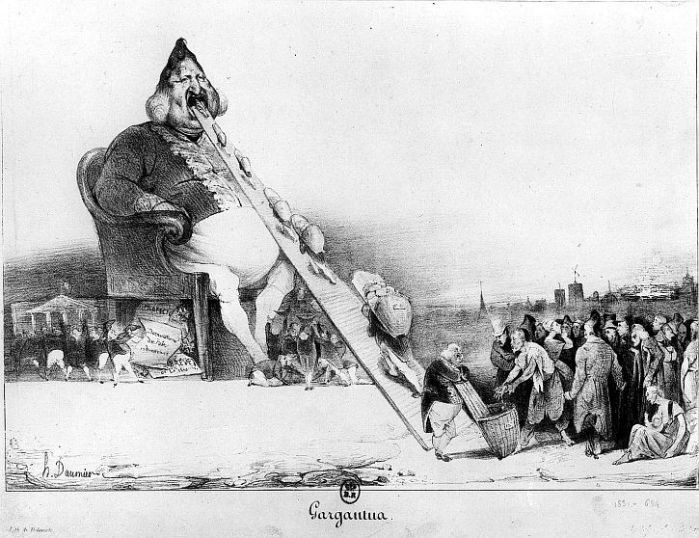

Honoré Daumier’s Gargantua: the king as a devourer of his subjects’ hard-earned money

At the lower right of the cartoon, Daumier represents poor taxpayers dressed in rags being forced to empty their pockets into the baskets. By the feet of the king are gathered well-dressed members of the bourgeoisie in tricorn hats, availing themselves of any coins which may fall from the baskets as they are carried up towards the king’s mouth. Under the king’s commode are papers excreted by the king after consuming the money – documents granting honours and privileges to the chosen few below, who then can be seen rushing off towards the National Assembly. This caricature of the king led to Daumier’s imprisonment for six months in 1832. Soon after, the publication of La Caricature was discontinued, but Philipon provided a new field for Daumier’s activity when he founded Le Charivari.

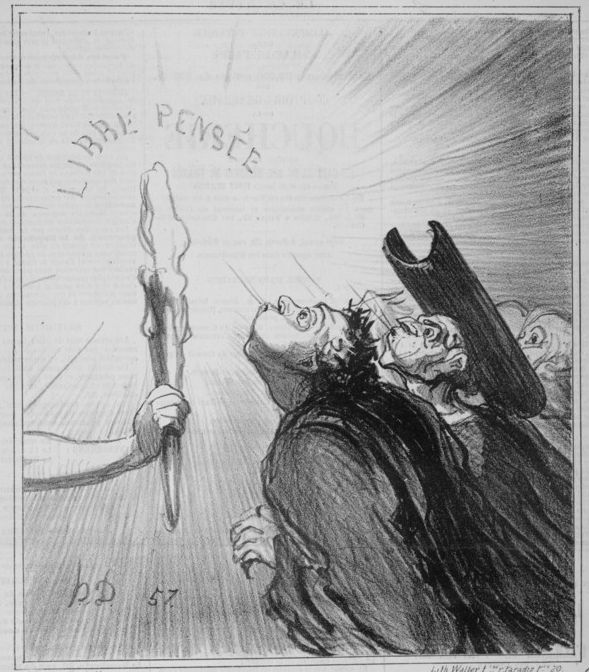

Honoré Daumier, Répétition générale du concile, 1869

The Catholic Church was a favourite target for caricaturists in 19th century France – as seen in this satire on the Catholic clergy by drawn by Daumier in 1869. Called ‘Répétition générale du concile’ (‘Dress rehearsal for the Council’), it was inspired by the First Vatican Council, convoked by Pope Pius IX, which opened in December 1869. The Council was convened to deal with the problems for the Church of the rising influence of rationalism, liberalism, and materialism (for example, in relation to the doctrine of Papal infallibility). Daumier doesn’t hold out much hope for change, portraying the clerics blowing out the flame of freedom of thought.

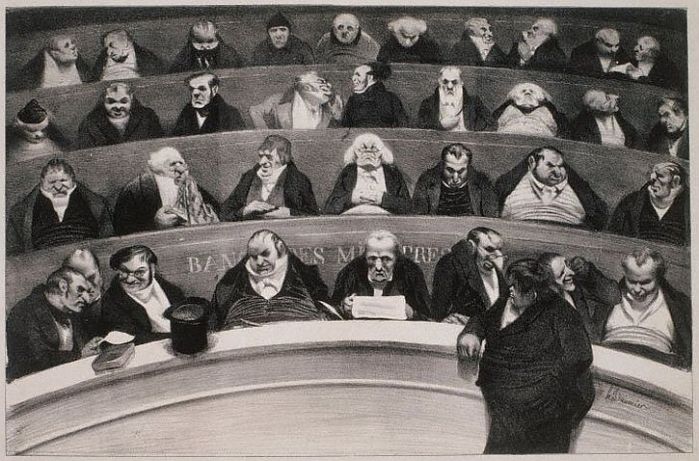

Honoré Daumier, The Legislative Belly, 1834

Cartoonists continued to mercilessly lampooned everything about the July Monarchy, as Louis-Philippe’s reign was known – his ministers, their censorship of the press, and their role in the inequalities of French society. Daumier’s favourite targets were politicians and lawyers (among my favourite Daumier works are the dozens of busts of politicians and lawyers he made from unbaked clay). In ‘The Legislative Belly’, drawn in 1834, he caricatures a meeting of the National Assembly, portraying members of the Centre Right faction of Louis-Philippe’s legislature as bloated, self-important men who struggle to stay awake: the embodiment of idleness, conceit and corruption.

In one of Daumier’s most celebrated images he depicts the gruesome aftermath of an attack by government troops on a working class quarter in which an entire family were killed after a riot.

Honoré Daumier, Rue Transnonain, le 15 avril, 1834

In an article for Aljazeera.com this week, Arthur Goldhammer writes:

There is an old Parisian tradition of cheeky humour that respects nothing and no one. The French even have a word for it: gouaille. Think of obscene images of Marie-Antoinette and other royals, of priests in flagrante delicto with nuns, of devils farting in the pope’s face and Daumier’s caricatures of King Louis-Philippe, whom he portrayed in the shape of a pear. It’s an anarchic populist form of obscenity that aims to cut down anything that would erect itself as venerable, sacred or powerful.

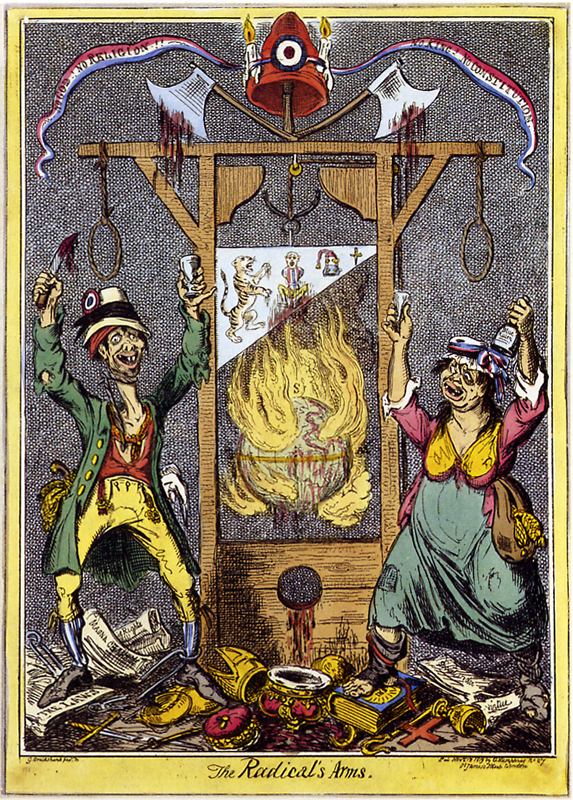

George Cruikshank, The Radical’s Arms, 1819

There was once an English tradition of caricature as anarchic and as extreme as the French one continues to be. From the mid-18th century through to around 1830, English caricaturists such as Rowlandson, Gillray, Cruikshank and Newton skewered the pretensions of monarchy, politicians, clerics and just about anyone, with wild, anarchic abandon.

We could begin with George Cruikshank’s The Radical’s Arms, published in 1819, the year of sweeping demonstrations demanding the right to vote, and of the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester. Cruikshank’s response is to pillory the radicals as French revolutionaries, their tricolour ribbon inscribed ‘No God! No Religion! No King! No Constitution!’, while below, surmounted with the Phrygian cap and cockade,is the guillotine. An emaciated man and a drunken woman dressed in rags dance gleefully on royal and clerical regalia.

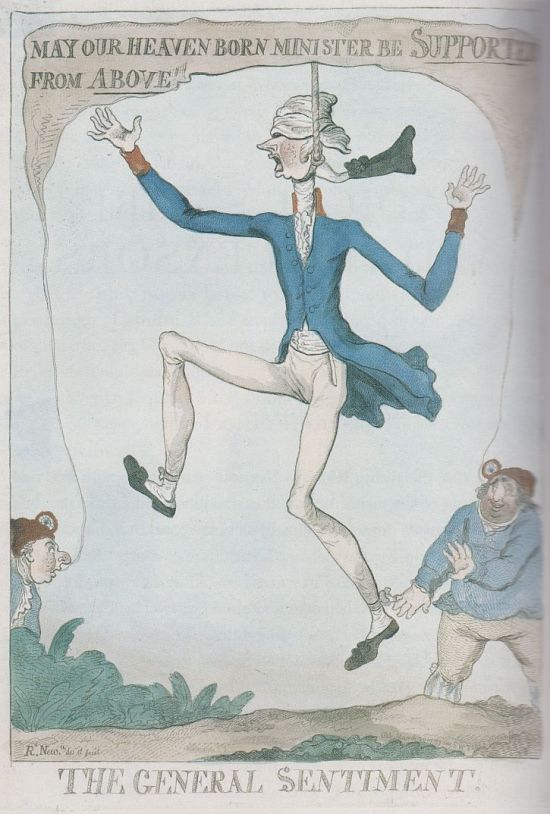

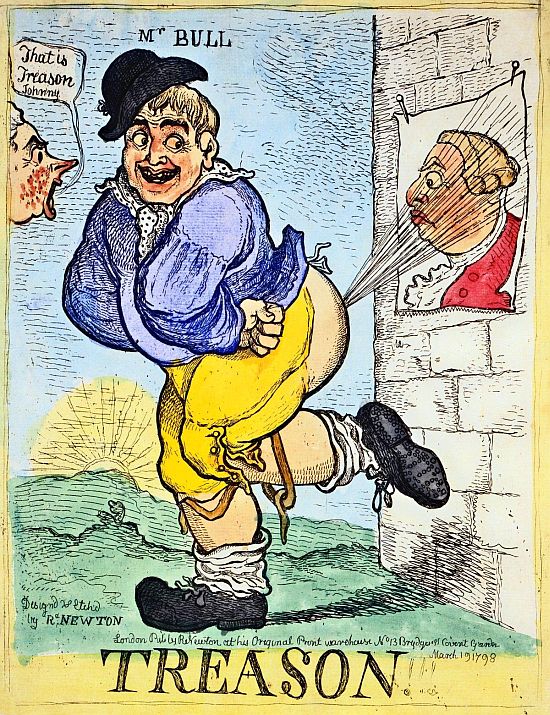

Richard Newton, The General Sentiment, 1798

Earlier, in 1798, at the height of the revolutionary terror in Paris, the young Richard Newton etched and published two of the most daring prints in a tense decade. Both were published at the height of ruling class fears of sedition and the spread of radical ideas from the French Revolution. Treason!!! depicts a plebian John Bull farting defiance at a poster of George III, while Prime Minister William Pitt warns him, ‘That is treason, Johnny’. The General Sentiment, from a few months earlier, shows Pitt being hanged by the neck watched by his Whig opponents, Charles Fox and Richard Sheridan who are wearing revolutionary red bonnets and gleefully wishing ‘May our heaven born minister be supported from above‘.

Richard Newton, Treason!!!, 1798

If you’re looking for a no-holds barred attack on religion, Newton’s Practical Christianity, a cartoonist’s take on the hypocrisy (or ‘cant’ in the day’s terminology) of religious leaders who sanctioned the brutal treatment of slaves should serve quite well (though it only gains its full force with the title attached).

Richard Newton, Practical Christianity

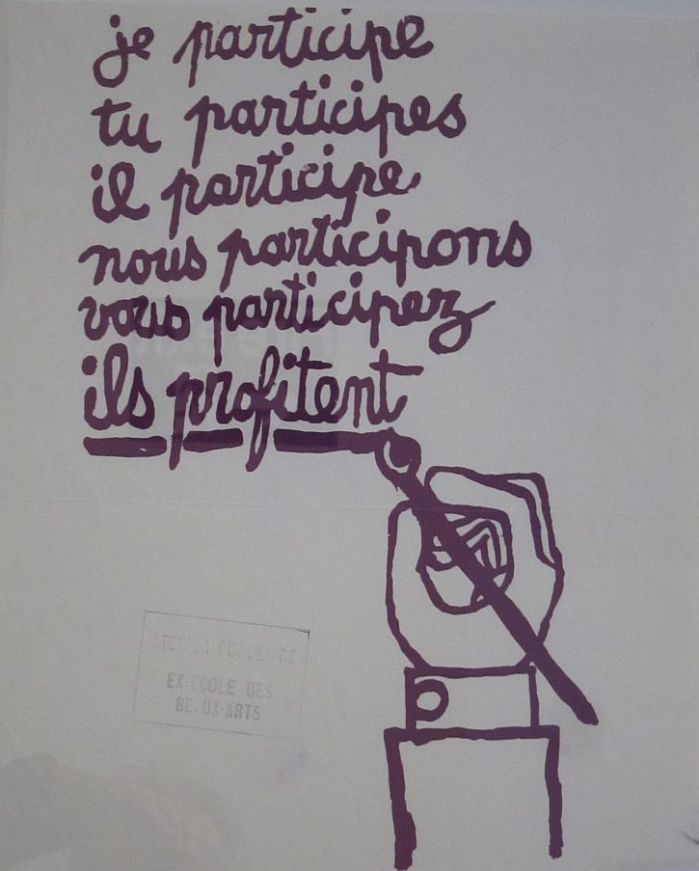

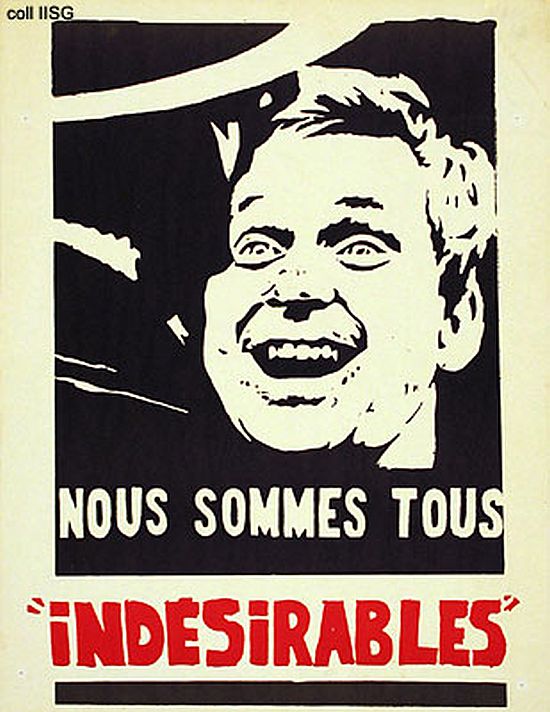

The vitality of French caricature came to the fore in 1968, another year of revolution on the streets of Paris, and the libertarian source for Charlie Hebdo, born in the aftermath of the events of May 1968. That was when the Atelier Populaire, the poster workshop that emerged during the May events in Paris, produced the striking images that have become iconic of those days.

In May, as workers and students took to the streets in an unprecedented wave of strikes, walkouts and demonstrations, the Atelier Populaire was formed. The faculty and student body of the Ecole des Beaux Arts were on strike, and a number of the students gathered in the lithographic department to produce the first posters of the revolt.

On May 16th, art students, painters from outside the university and striking workers decided to permanently occupy the art school in order to produce posters that would, ‘give concrete support to the great movement of the workers on strike who are occupying their factories in defiance of the Gaullist government’. ‘La Chienlit, C’est Lui’ (‘The shit in the bed is him’) was one of the most scurrilous attacks on President de Gaulle.

The posters of the Atelier Populaire were designed and printed anonymously and were distributed for free. They were seen on the barricades, carried in demonstrations and were plastered on walls all over France. Their bold and provocative messages were extremely influential and still resonate today.

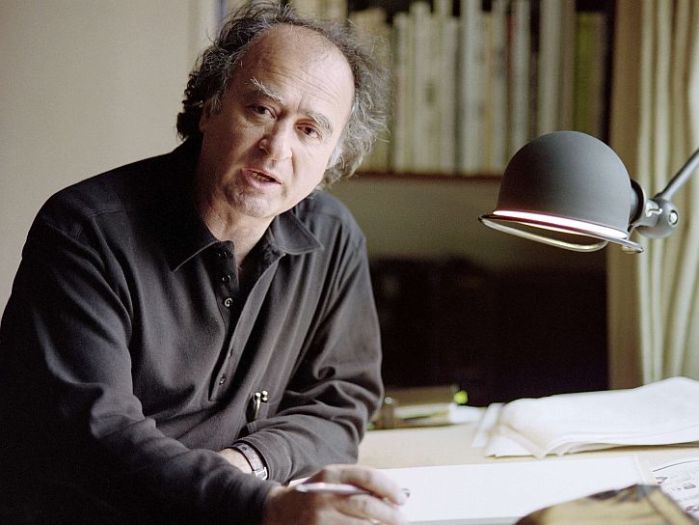

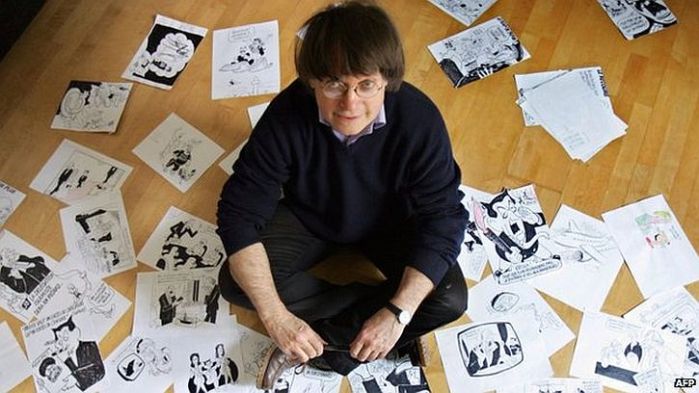

It was during the revolt of May 1968 that Georges Wolinski, the son of a Tunisian-Jewish mother and a Polish-Jewish father, co-founded the satirical paper L’Enragé. A year later Hara-Kiri Hebdo was launched. When the magazine was banned, it soon reappeared as Charlie Hebdo, with Wolinski as its first editor. Wolinski and Charlie Hebdo co-founder Jean Cabut (or Cabu) belonged to the generation of May 1968 – the generation that had revolted against the heavy hand of Charles de Gaulle’s paternalism with a belief in unlimited liberty, unrestrained sex, drug taking and, above all, the freedom to mock all forms of moral and religious authority.

Georges Wolinski

Jean Cabut

There has been much debate in the last few days about how far cartoonists should go – whether they should exercise any restraint in their work (as those at Charlie Hebdo clearly did not). Jet Heer in a thoughtful piece for the Boston Globe and Mail places their approach in the French tradition of caricature:

France’s culture of robustly virulent image-making has a downside. To this very day, it’s common for French cartoonists to use racist stereotypes of the most degrading form. In French magazines that feature comics, you can see cannibalistic Africans; hook-nosed and avaricious Jews of the Shylock variety; and wily, slant-eyed Asians who look as though they’ve escaped from a Fu Manchu novel.

Charlie Hebdo certainly trades in such racially incendiary images; a cover once depicted the sex slaves of Boko Haram as screaming, pregnant welfare queens. In their defence, the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo would say that they mock everyone equally. But in a racially stratified society, making fun of novelist Michel Houellebecq for his smoking and drinking is hardly the same as conflating sex slaves in Africa with welfare recipients in France.

As a rule of thumb, satire that punches up is more commend- able than satire that punches down. To attack the powerful is noble; to mock the weak is ignominious. Yet, in the context of France, there’s ambiguity about whether mocking Islam is punching up or down. As a global religion, it is a powerful force, and as worthy of satire as the Catholic church (which Charlie Hebdo often derides, sometimes in the most offensive way possible: One cover re-imagined the Christian trinity as a threesome, with the Holy Spirit sodomizing Jesus, who in turn was sodomizing God.)

But in France itself, Islam is the religion of the marginalized, those who, even if they are born in France, are seen by many of their fellow citizens as forever foreign.

Within the context of French radical secularism and anti-clericalism, making fun of Islam is perfectly acceptable and, indeed, morally necessary: Like all religions, Islam is seen as inherently oppressive, and so mockery is liberating. But this type of no-holds-barred irreverence can be blind to its own role in maintaining atavistic prejudices.

Yet, to describe Charlie Hebdo simply as a racist magazine is also a simplification: It has done many cartoons making fun of such racist French politicians as Marine Le Pen, who is currently trying to exploit the terrorist attack on the journal. Charlie Hebdo is best seen as an anarchic publication, willing to tackle anything taboo.

Part of what’s going on here is the clash of two ancient traditions – that of a subset of fundamentalist Islam, with its long-standing iconophobia; and that of France, with its tradition of aggressive cartooning.

Meanwhile, before researching this post I was unaware that a cartoonist was once shot dead in a London street in reprisal for his work. In the 1970s and 80s, Naji Salim al-Ali was one of the best-known Palestinian cartoonists who drew cartoons critical of the Israeli occupation, as well as others that were harshly critical of Palestinian leaders. He drew cartoons for newspapers in Kuwait, and while living there was often detained by police and had his work censored. After finally being expelled from Kuwait, he moved to London. In 1979 he was elected President of the League of Arab Cartoonists.

His best-known character, Handhala, is a symbolic representation of the Palestinian people, a little boy, barefoot and wearing ragged clothes. Handhala always has his back turned to the viewer, his hands clasped behind him (his figure has more recently been used by the Iranian Green Movement).

On 22 July 1987, al-Ali was outside the London office of the Kuwaiti newspaper Al Qabas , when he was shot at point-blank range in the middle of the street. He died five weeks later without regaining consciousness. A suspect was arrested, who admitted to being a double agent, working both for Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organization and Mossad, the Israeli intelligence organization.

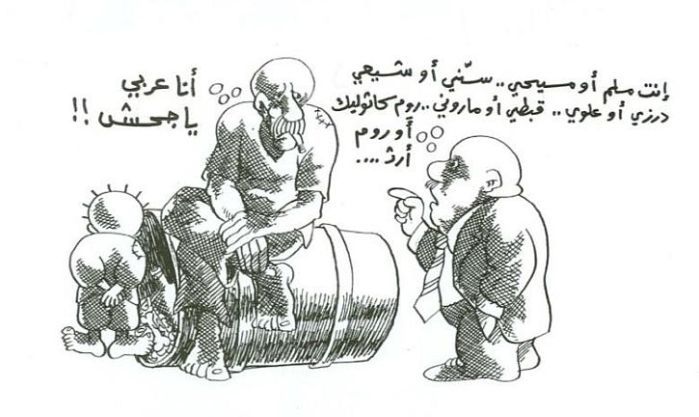

Naji Al-Ali, ‘I’m an Arab, asshole!’

In this currently very pertinent cartoon, al-Ali comments on sectarianism. The image shows a man asking another man: ‘Are you Muslim or Christian? Sunni or Shiite? Druze or Alawite? Coptic or Maronite? Orthodox or…’ The second man suddenly interrupts him by replying: ‘I’m an Arab … asshole!’

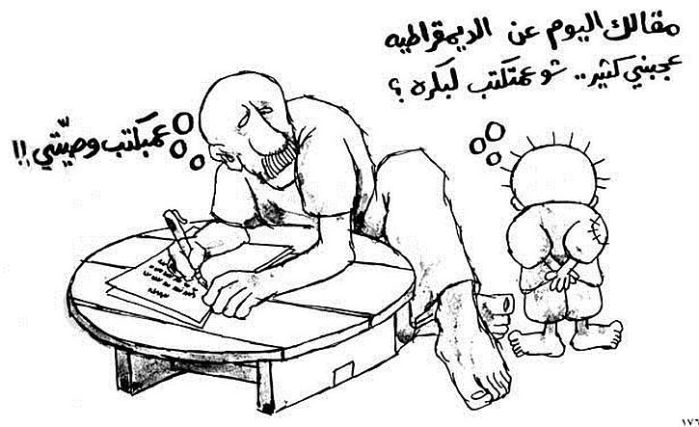

Naji Al-Ali, ‘I’m writing my will’

Another cartoon that speaks powerfully to the present moment is this one, in which al-Ali reflected upon how Arab regimes tended to deal with democracy and freedom of expression. Handala is telling the man, a journalist, how much he likes the article he is writing on democracy. Handala asks the man whether he’s writing for tomorrow? The man replies: ‘I’m writing my will.’

And so to this week:

David Pope, Australia

Francisco J. Olea, Chile

Jean Jullien, France

Lucille Clerc, France

Michael Adder, Canada

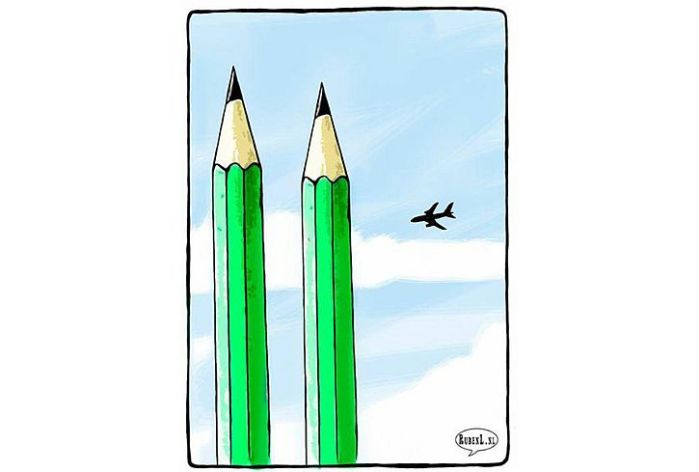

Ruben Oppenheimer, Netherlands

See also

- 23 Heartbreaking Cartoons From Artists Responding To The Charlie Hebdo Shooting

- 15 cartoonists respond to the attack against Charlie Hebdo

- Honoré Daumier – Lithographs and Caricatures

- Daumier’s satirical art hits with the force of a drone attack: Jonathan Jones, Guardian

- Strange seriousness: discovering Daumier by Roger Kimball (New Criterion)

- City of Laughter: bawdy and scurrilous 18th century London

Gerry, once again you capture my mood and inform me with your journalism.

Thanks

Andy

Thanks for this….Is it possible to site other original sources besides Ed V from the Observer? Thanks for putting this together….

Thanks, Margaret. I’ve added links to most of the pages I consulted.

Shared … Well reseached and informative, thank you.

Gerry

Have you read Chris Hedges on this:

http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/a_message_from_the_dispossessed_20150111

I find that he usually gets to the core of the issue.

Excellent review, very insightful. Thanks. I love this blog

Boston Globe and Mail ? Maybe Toronto.

You’re right! Apologies.

Hi Gerry

Any reason why you have chosen not to show my comment, which in turn drew attention to Chris Hedge’s article of today in Truthdig? I would hope that there has been some mistake as it would be ironic to decide to censor a comment on this particular topic.

My mistake, Yossi, I had seen it and then read Chris Hedges article (thought it very good) but forgot to press the approve button. Definitely no censorship! A similar point to Hedge’s is put forward by Julian Baggini in this Guardian article :http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jul/13/radicalisation-brainwashing-british-men-syria-julian-baggini

To add to the discussion of this topic and all its complexities: this report in which the Guardian investigates the background of the killers seems to bear out Hedge’s analysis (Charlie Hebdo attackers: born, raised and radicalised in Paris: http://bit.ly/17BaJt1) while Mehdi Hasan’s polemic in New Statesman ought to be considered seriously (As a Muslim, I’m fed up with the hypocrisy of the free speech fundamentalists: http://bit.ly/1C2CmE3)

Very interesting and beautifully put together piece. I do not disagree with anything said here… it’s just I cannot think of what’s going on in Europe without also lamenting for people who are victims of terrorism all over the world.

I want to march for the people of Nigeria where atrocities are sadly way too common. I want to hold a vigil for anyone who’s been taken from their homes and families.

Thanks for this, Gerry; I’ve passed it on to secondary schoolchildren. Thanks also for all your work. I read each piece yet haven’t previously given any sign of appreciation; I hope you find the energy to keep going.

Francis

Thank you very much indeed, Francis. Words like yours will certainly encourage continued blogging!

Reblogged this on stranded at low tide.