Last night’s Channel 4 documentary, The Art of War, presented by Jon Snow, was an impassioned and absorbing survey of the ways in which British artists have responded to the horrors of war and, since the First World War, challenged the idea that war art should simply celebrate valour, victory and glory. Snow traced this critical tradition from the artists of the First World War – Richard Nevinson and Paul Nash – via the work of Stanley Spencer and Henry Moore in the Second World War, to the work of contemporary artists such as Jeremy Deller and Steve McQueen. He demonstrated how Britain’s war artists have pushed the boundaries in their determination to express the pain and tragedy of war.

Richard Nevinson was under the spell of the Italian Futurists movement when he was appointed an official war artist in 1917. At first his paintings expressed the Futurists’ exultation in the drama and modernity of war, but their tenor soon changed, as a result of his experience as an ambulance driver. His painting Paths of Glory (above) was initially banned by the military censors, but Nevinson managed to display it during the war, attracting attention by taping ‘censored’ across the image. The ‘paths of glory’ have led these soldiers to death in a wasteland, imprisoned by barbed wire, faces down, anonymous and unrecognisable, slowly decomposing into the landscape.

In La Patrie (above), Nevinson used his own memories of what he had seen as an ambulance driver in Dunkirk following the early fighting around Ypres.

The artistic reputation of Paul Nash was just beginning to take off when the war broke out. Nash joined the Artists’ Rifles and saw service in the Ypres Salient before being invalided home. While he was recovering he exhibited works that depicted the desolate landscapes of the trenches, which led to Nash becoming an official war artist. We Are Making a New World (above) is one of the most memorable images of the First World War, the title mocking the ambitions of the war, as the sun rises on a scene of the total desolation.

In early 1918 he was commissioned to paint a Flanders battlefield for a Hall of Remembrance (which was never completed). In depicting one of the most battle-scarred areas of the Ypres sector, Nash shows two human figures overwhelmed by a hellish landscape of flooded shell craters, shattered trees, concrete blocks and corrugated iron.

Paul Nash also responded to the Second World War, most memorably with Totes Meer (above). This painting, the title of which is German for ‘dead sea’, was inspired by a dump of wrecked aircraft at Cowley in Oxfordshire. Nash based the image on photographs he took there: ‘The thing looked to me suddenly, like a great inundating sea … the breakers rearing up and crashing on the plain. And then, no: nothing moves, it is not water or even ice, it is something static and dead’.

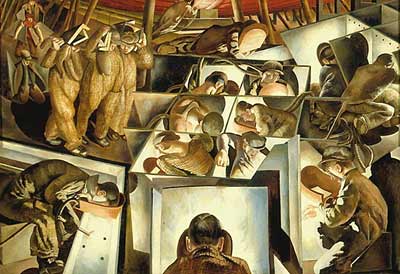

In The Art of War, Jon Snow was most visibly moved when visiting the Sandham Memorial Chapel at Burghclere in Hampshire, which is decorated with an outstanding series of large-scale paintings by Stanley Spencer (above). The images were inspired by his experiences as a First World War medical orderly and soldier in Macedonia, and are considered to be among his finest achievements.

The chapel was commissioned by Mary and Louis Behrends as a memorial to Mary’s brother, who died in Macedonia. The main painting, The Resurrection of the Soldiers (above), shows soldiers climbing out of their graves bearing white crosses and embracing their dead comrades. One man kneels at Christ’s side, his head in his lap, one man caresses a turtle, while another clasps a dove to his chest. Spencer wrote of the painting:

During the war, I felt the only way to end the ghastly experience would be if everyone suddenly decided to indulge in every degree or form of sexual love, carnal love, bestiality, anything you like to call it. These are the joyful inheritances of mankind.

In his film, Snow said:

Had his paintings been for a Wren church in the city, Spencer might even now be celebrated as the creator of our own Sistine Chapel. From the outside, the Sandham Memorial Chapel is unremarkable. Step inside and you are drawn into an account of war no artist has ever previously conjured.

Some of the best-known art works of the Second World War are Henry Moore’s sketches and watercolours of Londoners sheltering in the Underground during the Blitz. After the outbreak of war in 1939, Moore commuted from his home in Kent to London where he was teaching at the Chelsea School of Art. He began making drawings of people sheltering in the Underground during the German bombing raids and these came to the attention of the War Artists Advisory Committee, chaired by Kenneth Clark, then Director of the National Gallery. Moore was commissioned to make larger and more finished versions. When the drawings were exhibited in 1940 and 1941 they proved very popular with the public.

Returning to the work of Stanley Spencer, Jon Snow discussed his eight epic Second World War friezes, Shipbuilding on the Clyde, which depict the various stages of work in the shipyard- from riveting and pipe-bending to welding and rope making. Spencer was commissioned to paint civilian war efforts and he immersed himself in every aspect of the Glaswegian shipbuilding process to produce these images.

Snow concluded his survey by examining British Artists’ responses to recent conflicts. He discussed Jeremy Deller’s Baghdad, 5 March 2007 (aka It Is What It Is) with the artist, who described his experience of taking the work – a car destroyed in a 2007 truck bomb attack among the book stalls of Al-Mutanabbi Street in Baghdad – on tour around the United States.

Of this work, Jonathan Jones wrote in The Guardian:

With his new work, Baghdad, 5 March 2007, at the Imperial War Museum, he makes us see real death. It is the closest he could get, within the parameters of public display, to laying out the bodies of Iraq’s killed on the floor of the gallery.

A dismembered body is what you immediately think of when you come into the museum and see a car destroyed in a 2007 truck bomb attack among the book stalls of Al-Mutanabbi Street in Baghdad, an attack that killed 38 people. Lying among the missiles, tanks and war planes in the museum’s main hall is the eviscerated corpse of what was once a car. It is more than wrecked. It appears to have been flung in the air, crushed, then burned in an inferno. It suggests a human body in a deeply perturbing way. First, because it is so flattened, with viscera of pipes and tanks sticking out. Then again it is scorched by fire to a colour that evokes dried blood. It looks curiously like Lindow Man in the British Museum.

That visual suggestiveness is not the work of a sculptor in a studio. Deller did not make this. He had the idea of exhibiting a car from a Baghdad bombing, was able to get his hands on one, and toured it around America as an object of curiosity before the Imperial War Museum made the brave decision to show it in their displays. The horrible sculptural quality of this relic is accidental, and it forces you to confront the real suffering of the people killed and wounded in Baghdad on that particular day. It is a simple enough thought: if the bomb did this to metal, what did it do to flesh?

The truth stares you in the face, while gleaming machines of death loom above. It makes you imagine not just this reality, but all the realities those weapons created, from a burned-out Panzer on the eastern front to a London street just hit by a V1. Deller has often created works of populist social theatre, but here he achieves something new: the most serious and thoughtful response to the Iraq war by any British artist.

Poet Abdul Zahra Zaki recites a poem outside the shell of the Al-Shahbandar café as part of a protest by artists and writers against the bombing of Al-Mutanabbi Street, March 8, 2007

The final piece chosen by Jon Snow was Steve McQueen’s Queen and Country. McQueen, collaborated with 160 families whose loved ones lost their lives in Iraq. He created a cabinet containing a series of facsimile postage sheets, each one dedicated to a deceased soldier. The Art Fund, the UK’s leading art charity, presented this cabinet to the Imperial War Museum in November 2007 and toured the work around the UK between 2007 and 2010.

Queen and Country was created by Steve McQueen in response to a visit he made to Iraq in 2003 following his appointment by the Imperial War Museum’s Art Commissions Committee as an official UK war artist. During the six days McQueen spent in Iraq, he was moved and inspired by the camaraderie of the servicemen and women that he met. He proposed that portraits of those who have lost their lives during the conflict be issued as stamps by Royal Mail.

An official set of Royal Mail stamps struck me as an intimate but distinguished way of highlighting the sacrifice of individuals in defence of our national ideals. The stamps would form an intimate reflection of national loss that would involve the families of the dead and permeate the everyday – every household and every office.

While discussions were under way with Royal Mail, Steve made Queen and Country – a cabinet containing a series of facsimile postage sheets bearing multiple portrait heads, each one dedicated to an individual, with details of name, regiment, age and date of death printed in the margin. The images were chosen by the families of the deceased.Viewers are invited to pull out the double-sided panels bearing the sheets from a wooden box and thereby create an intimate space to contemplate the imagery.

Steve McQueen: ‘Queen and Country’ (detail)

Until Royal Mail agrees to issue the stamps, the artist considers the overall work incomplete. The Art Fund is spearheading the campaign to gain public support for McQueen’s vision for Royal Mail to officially issue the stamps.

Steve McQueen with ‘Queen and Country’

Wonderful post. You might be interested in my recently published book ‘Ravilious in Pictures: The War Paintings’, available now from http://www.themainstonepress.com.

Yours

James Russell

Thank you, Gerry, for an excellent summary of Jon Snow’s programme on the British war artists.