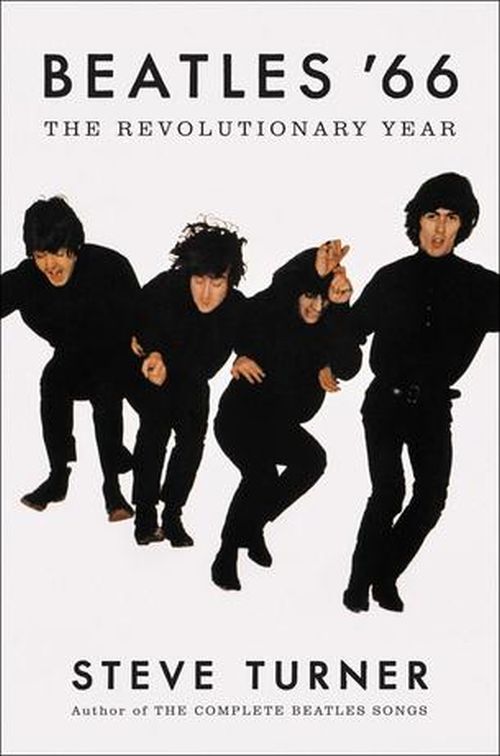

I had already read Jon Savage’s book 1966: The Years the Decade Exploded and seen the V&A exhibition, You Say You Want a Revolution? Records and Rebels 1966 – 1970 when, just before Christmas, Steve Turner’s book, Beatles ’66: The Revolutionary Year, fell into my hands. Would I be up for a return trip to the year now regarded as a turning point, not only in music but more widely in culture and politics? Could Turner turn a chronicle of the Beatles’ day-to-day activities that year into a readable and engrossing narrative? The answer was resoundingly affirmative.

The key aspect of Jon Savage’s book was that, though its central concern was with the music of 1966 – its ideas, attitudes and experimentation – it also focussed on the way in which music reflected the world in 1966 and was connected to events and ideas beyond pop culture. His argument was that 1966 was the turning point of the sixties when old and new values collided, and the various liberation movements asserting personal identity (black power, women’s right, gay rights, consumerism) took shape, sometimes explosively. The V&A exhibition took the same approach, choosing 1966 as the starting point for an examination of a series of revolutions in attitudes and behaviour which defined the Sixties and influenced subsequent decades.

Steve Turner’s focus is narrower, but in charting this one year in the life of the Beatles he aims show that this was a period in which they wanted to progress – and they did just that by opening themselves up to a wide range of cultural, political and philosophical influences – and no small amount of illicit substances:

They knew that the more they gave out, the more they needed to take in, and therefore they actively sought material that might challenge and stir them. … There was no shortage of entrepreneurs keen to turn the Beatles on to new fashions, music, art, books, experiences, philosophies, and even new technology.

Turner’s book traces the same dramatic arc as Savage’s. In a prologue, Turner notes that on 3 December 1965, with Rubber Soul just released, the Beatles were at the Odeon Glasgow, where support acts on the bill included Beryl Marsden and the Moody Blues. Two nights later, at the Empire, the Beatles played their last-ever Liverpool concert. As in Savage’s book, 1966 ends in December with John Lennon starting work on ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ – the beginning of the sessions which yield the Beatles’ greatest artistic triumph, Sgt Pepper:

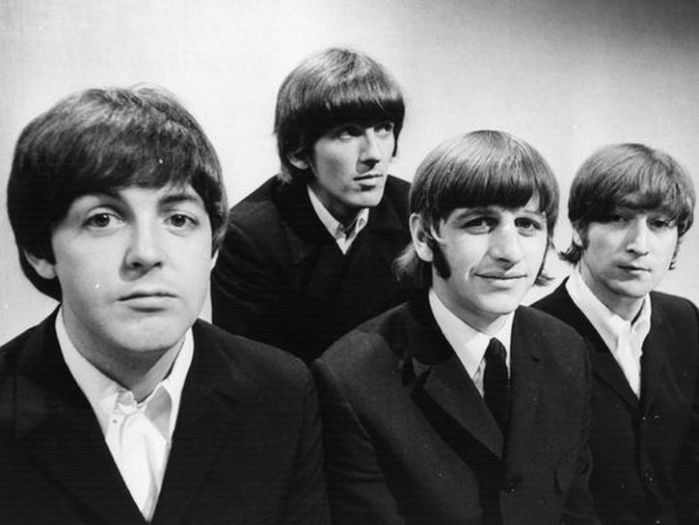

1966 was without question the pivotal year in the life of the Beatles as performers and recording artists. Before that they were the four loveable guys from Liverpool who wore identical suits on stage, played to packed houses of screaming (largely female) teenagers, played themselves in movie capers, and wrote jaunty songs chiefly about love. After 1966, they were serious studio-based musicians who no longer toured, wore individually selected clothes from Chelsea boutiques, wrote songs that explored their psyches and the nature of society, and were frequently considered a threat to the established order by governments around the world.

1966 was the year when the Beatles recorded Revolver, their most ground-making album to date, and began work on their unquestioned masterpiece Sgt Pepper. It was the year when they played their last live concert dates, George Harrison made his life-changing journey to India, and John Lennon met Yoko Ono at her art show in London. Along the way, they imbibed drugs and alluded to the experiences in song, made huge advances in their song-writing, utilised innovations in studio recording techniques, and aroused controversy and hostility from Birmingham, Alabama to Manila.

Like Mark Lewisohn, whose The Beatles Tune In I was reading this time last year, Steve Turner is a music journalist who has long ploughed a furrow as a Beatles expert. His first published article was in the Beatles Monthly in 1969, after which he wrote for music papers including NME, Melody Maker and Rolling Stone, interviewing a wide range of rock and pop musicians. He has written books on stars such as Marvin Gaye, Johnny Cash, U2 – and the Beatles. So Turner knows his stuff: Beatles ’66 draws upon his interviews with the Beatles and those who knew them made throughout his career, as well as interviews conducted specifically for the book, plus newspaper and magazine archives and an impressive range of books on the period and its music.

It’s fair to say that the broad outlines of the story Turner tells will be familiar to those love the Beatles, but the access which Turner has had over the years to the Beatles themselves and other key people such as George Martin and Ravi Shankar, plus his extraordinary attention to detail, make this a constantly interesting and worthwhile read.

Like some musical archaeologist, Turner has sifted through the sediments of the Beatles’ engagements and encounters, archived magazine and newspaper reports – a truly remarkable assemblage of documentary material, in fact – to produce a chronological narrative of the year, divided into twelve monthly chapters.

Turner brings his story to life, engaging this reader for the most part, though I might have preferred a thematic rather than day-by-day approach. Gradually, however, three significant themes begin to emerge from the detail.

The most important of these in terms of the group’s future musical development is the way in which, noticeably in 1966, each of the four began to embrace new interests and distinct characteristics – something which, by pulling in different directions, might have torn the Beatles apart. Instead, at least for a while, it strengthened them as a musical entity, making their work musically and lyrically richer and more adventurous. This was the main factor contributing to the revolutionary nature of Revolver and the music that led towards Sgt Pepper.

Revolver was the first record in which we became aware of the Beatles not as a unitary pop group, but as four individual musicians, each responding to the shifting tectonic plates of the culture around them in different ways. Meticulously, Turner details this process happening, particularly during the first three months of 1966 as the group, having finished Rubber Soul, take three months off before beginning work on Revolver. This was their longest break since the start of their recording career, and each Beatles went his own separate way after years of touring and working on new songs as a unit. It’s true that the group had begun to explore individual concerns on Rubber Soul, but during 1966 this became life’s main mission, particularly for George, Paul and John.

For Paul, this meant pursuing his interests on the London avant-garde scene: art at the Indica gallery and bookshop which opened in January, theatre (stimulated through his relationship with Jane Asher), and avant-garde composers such as Berio, Stockhausen and Reich. He had already begun collecting art, and in February bought an oil painting by Peter Blake, who the following year would be commissioned to produce the cover art for Sgt Pepper. In the same month Paul attended a lecture by Luciano Berio – who had worked with Cage and Stockhausen, and taught Steve Reich – which introduced him to the concept of music as a collage of cut-up tapes and electronic as well as acoustic sounds.

Meanwhile, John was the one ‘full of contradictions’:

He was the hardest-working musician and songwriter who was terminally lazy; the champion of the downtrodden who liked to be chauffeur-driven in a Rolls-Royce with tinted windows and a TV; the dedicated artist who could say, ‘I want the money just to be rich.’

John was an avid reader who tended towards introspection, but also had an impulsive interest in contemporary political issues and spiritual matters. It was this that led him to sound off about Christianity when Maureen Cleave interviewed him for the Evening Standard. Though the interview was published in March, his comments went unnoticed in Britain, a country where church-going and religious affiliation figures were dropping away steeply. What he said wasn’t particularly controversial in secular Britain, but months later, when the interview was published in America and journalists and disc jockeys in the South latched onto his words, it would fuel a wildfire:

Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. … We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first – rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity.

More significantly, the interview revealed John as someone not content with wealth and fame as a pop musician: a man who wanted to go beyond the role of ‘mere’ entertainer (in the autumn he would explore the possibilities of film acting with a small role in Richard Lester’s black comedy, How I Won the War).

You see, there’s something else I’m going to do, something I must do – only I don’t know what it is. That’s why I go round painting and taping and drawing and writing because it may be one of them.

Like Paul, John was interested in everything that was happening in London, and keen to express himself in new and deeper ways than the traditional three minute pop song allowed. With Paul he’d been listening to electronic works by avant-garde composers, and in April, a third of the way through recording songs for Revolver, he came up with ‘one of the most extraordinary songs in pop music so far’: ‘Tommorrow Never Knows’.

A track evoking the experience of an LSD trip, drawing indirectly on a text of Tibetan Buddhism, incorporating random tape recordings played backward, and distorting the vocal to sound like the chanting of an Eastern monk. […]

What it had in common with the works of the electronic composers they’d recently been listening to was that it was a statement in sound at a particular moment with little likliehood of ever being performed live.

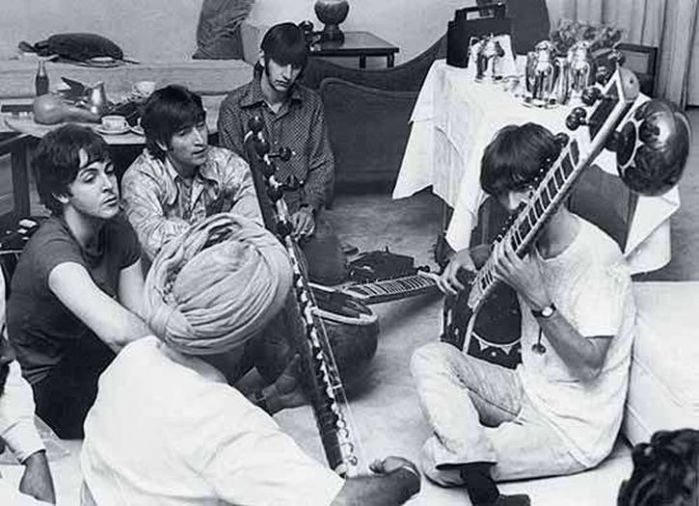

In George’s case, 1966 was the year in which, apart from getting married, he pursued his interest in Indian culture and music in a deeply serious way. A year earlier, during a break in the filming of Help!, he had picked up a sitar left on the set as a prop and attempted to play it. Later, David Crosby had introduced him to albums by sitar maestro Ravi Shankar, and George had taught himself enough to play the instrument on Rubber Soul‘s ‘Norwegian Wood’ (a first for western pop music).

Then, in June, after a concert by Shankar at the Royal Festival Hall, George met the Indian musician at the home of mutual friends. Embarrassed by his inadequacy on the instrument, George asked Shankar to be his mentor. He began to take lessons from Shankar while he was in London, and then over a more extended period in India in the autumn. The result would be sitar tracks for ‘Love You To’ and Tomorrow Never Knows’ on Revolver and his composition ‘Within You Without You’ which opened side two of the Sgt. Pepper LP.

Linked to these individual explorations was a desire on the part of all four Beatles to keep up with the opposition. This is a theme Steve Turner draws attention to repeatedly. It’s also a defining characteristic of the popular music scene in 1966: everywhere, young musicians were pushing at the boundaries of what could be expressed in a 4 minute single or across two sides of an LP. The Beatles were alert to the innovative lyrics and sounds emerging from British rivals like the Stones, The Who, and the Yardbirds, from the psychedelia of the West Coast, and especially from the minds of the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson – and Bob Dylan. 1966 was no walkover.

In May, three days after the Beatles had been in the studio, adding brass to ‘Got To Get You Into My Life’, John and Paul heard Pet Sounds, two months before its UK release, played for them in his London hotel room by Bruce Johnston. After listening silently as the album was played twice, ‘they immediately went to a piano … and began playing chords and discussing a song with each other in a whispered conversation.’

For John and Paul Pet Sounds endorsed their own recording adventure and inspired them to reach even higher. They identified with Wilson’s vision of transforming the LP into a cohesive unit and admired his writing, instrumentation, and vocal arrangements. […] John liked it so much that he called Wilson to tell him that it was the greatest LP he had ever heard.

This mutual respect only increased when, on 27 August in California, Paul and George met Brian Wilson who played them the Beach Boys’ next single, ‘Good Vibrations’

In an earlier hotel room encounter that month, Paul and John had played Dylan pressings of their latest songs:

The ace in Paul’s pack was ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, proof, he thought, that the Beatles were at the experimental cutting edge of pop. Dylan didn’t show any emotion then turned to him and said, ‘Oh, I get it. You don’t want to be cute anymore.’

They were difficult to fathom, he surmised, not because they were deep but because Dylan used literary tricks to dazzle his listeners. John didn’t believe that the madmen, judges, jugglers, and thieves that thronged Dylan’s songs were anything other than nice sounding words to sing and exotic images for fans to puzzle over. He felt the enigmatic lines that often sounded like proverbs had no real wisdom at their core.

Another major thread in Steve Turner’s narrative concerns the Beatles’ mounting dislike of touring, and growing interest in focussing their efforts on studio recording. They had reached a point where neither they nor the audience could hear anything, they weren’t improving their skills as musicians (as they had done during their Cavern and Hamburg apprenticeships), they weren’t proudly showcasing their latest music but instead songs that were three or more years old. Remarkably, the Beatles never played a single track off Revolver, released just days before they set off on tour. Most importantly – they weren’t enjoying themselves. The weight of their celebrity felt more burdensome than ever.

In June, their world tour began in Hamburg, followed immediately by an Asian leg that took in Japan and the Philippines. Turner documents how miserable the Beatles’ were when they were on the road: a nonstop barrage of press conferences, travel, and boring meetings with local dignataries. When they were onstage, they could barely hear themselves play over the screaming of their fans. Offstage, they couldn’t go anywhere.

The Asian leg ended in July with a terrifying incident in the Philippines after they were judged to have snubbed the dictator Marcos and his wife. Manhandled at the airport, and police protection withdrawn, the group left the country only after being stripped of concert proceeds.

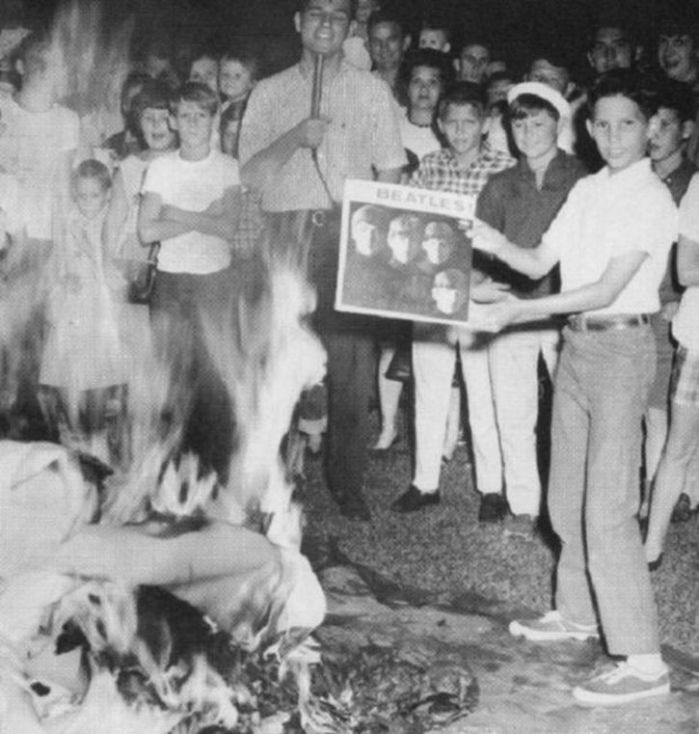

If anything, America was even worse. Just before they landed, Maureen Cleave’s Evening Standard ‘We’re more popular than Jesus’ interview was published in America. In Birmingham, Alabama, disc jockeys at a local radio station urged listeners to send in their Beatles records to be destroyed. Rapidly, the situation escalated with a series of mass burnings of Beatles’ discs. In South Carolina, the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan nailed several Beatles albums to a cross and set it aflame, while Imperial Wizard Robert Shelton of the Klan’s Alabama chapter declared the Beatles brainwashed by the Communist party and criticised them for their support of civil rights.

But, as Steve Turner makes clear, it wasn’t just the physical danger that wore down the Beatles. Once, playing live had been their lifeblood, but now it was stripped of everything that had made it fulfilling. The arenas were too big, the screams of the fans were too loud, and their amplifiers too small: they could not be heard, they couldn’t hear themselves. It all seemed so pointless. The boredom of playing the same old songs each day, unable to perform their latest work because of the technical limitations of the time, they wanted out.

In November, the Beatles finally announced that they would not tour again. On 8 November, John met Yoko at the Indica Gallery, and later that month he began to record ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, the song he had begun to write whilst filming How I Won the War in Almeria. In December, the group were at work on ‘Penny Lane’, while on the 18th the Guiness heir Tara Browne, driving at high speed through South Kensington, failed to notice that the lights had changed and was killed in a car crash. In the new year, it would be John’s inspiration for ‘A Day in the Life’.

Let me take you down…

So ended 1966, a that changed everything for the Beatles. The natiure of that transformation is presented in crafted detail by Steve Turner. For Beatles aficionados, there are no great surprises here. But Turner is an expert on the Beatles and brings his considerable knowledge and research to bear on a story that tells – for the large part in engrossing detail – how the Beatles in their changes reflected the swirling cultural and political currents of the time.

Declaration: my copy of Beatles ’66 was kindly supplied by the author.

Thanks for the review Gerry. I love the stuff you write about – which is why I sent you the book! The photo you used of Dylan and Lennon is not from Eat The Document. It’s photoshopped. I had seen that photo and another one of the two of them in the back of Lennon’s car that I wanted to use in the book. I contacted Dylan’s management who were very helpful and carefully trawled through Eat The Document to get a grab-shot for me but could find no place where Dylan and Lennon were both featured in the same image! While I’m online with you Gerry – here’s blog that you might appreciate (if you’re not already onto it). This girl – https://www.brainpickings.org/ – is full of great suggestions and links to interesting stuff. The only downside to it is I know I’l always spend so much time on it because it’s so rich and I’ll end up ordering yet another book without the shelving to cope. Keep up the good work Gerry. I admire your range of interests, your analytical ability and your willingness to share with others. Best, Steve Turner

Thanks, Steve, for comment and generosity. Photoshopped eh? Sneaky sods. I’ve corrected the caption. And/ yes, brainpickings is a great blog, lots to read, stimulate and explore further – and a weekly email you can sign up for. As you say, terrible time-waster, but I recommend it to other visitors! Oh, and on his excellent Pandaemonium blog, Kenan Malik does a regular roundup of recent essays and stories from around the web which always captures something interesting (https://kenanmalik.wordpress.com/)

I love Beatles! Have you been to Rishikesh in India where they lived for sometime and wrote their White Album? I went to the ashram they stayed in last month, it’s an experience every Beatles fan must have once!

Read more here https://himadri7.wordpress.com/2017/01/26/rishikesh-is-not-just-about-rafting

I visited the site of the ashram in 2006 and Rishikesh again in 2012. The ashram was very overgrown when I went round – and heavily protected – but I believe that they are going to open it up for visitors. Best, Steve Turner

It was open when I went two months back in December 2016.

Good to know Himadri. There’s clearly an opportunity for Rishikesh to turn it into a tourist attraction rather than let it be swallowed up by the jungle.