We had bought our tickets weeks ago: a good move, since David Hockney’s show, A Bigger Picture, at the Royal Academy is now sold out for its entire run.

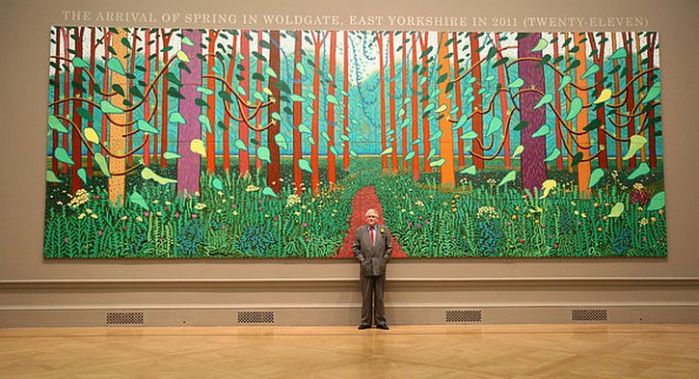

And show it is: this realisation hit me when I entered the gallery devoted to the arrival of spring. This huge room brings to mind Hockney’s long involvement with theatrical spectacle, designing sets for the opera. Stand at the centre of this overwhelming display and you are surrounded by 51 large prints, a series entitled The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 that records the transition from winter through to late spring on one small road. The prints originate from drawings made on an iPad, an instrument that didn’t exist when he accepted the Royal Academy’s invitation in 2007 to mount an exhibition. Dominating all, on the end wall, is a massive 32-canvas painting that represents the theme’s vibrant crescendo – The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 (twenty-eleven). This is a theatrical experience, a stage set with the viewer at the centre of the drama.

This is an astonishing painting, with vibrant colours and disembodied, Rousseauesque leaves and tendrils that seem to float among the vivid orange and purple vertical slashes of the tree trunks. On the woodland floor, spring flowers and green ferns form a William Morris tapestry. It represents the acme of Hockney’s intent to share his rediscovery of the English landscape, and to assert the importance of careful observation of the small but significant changes that unfold daily in the natural world around us.

This exhibition reveals Hockney as a showman. He was invited to stage this exhibition in the autumn of 2007, immediately after the Royal Academy display of his huge painting, Bigger Trees near Warter, and he has spent the last four years not just painting furiously, but also playing a central role in planning the layout of the whole show, room by room, as if the RA were his own giant stage set (which it is, for the time being). It’s a show in that you sense Hockney actively wants to communicate his feelings about art and representation, nature and looking, as well as putting on a great two hours or so of entertainment – a great quantity of paintings to look at, new technologies to marvel, a stunning high definition film show, and even a bit of ballet dancing with lots of jokey allusions.

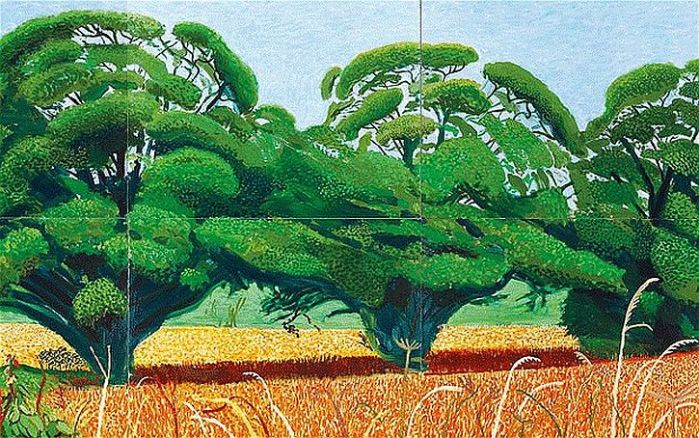

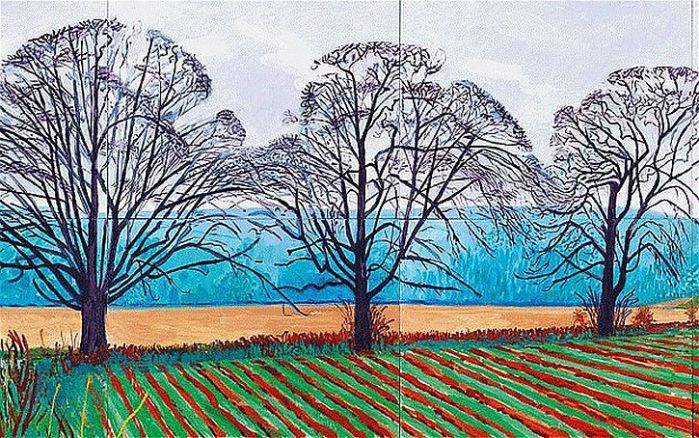

In the first room you enter you encounter four immense oil paintings of trees near the Yorkshire Wold village of Thixendale, about 20 miles west of Bridlington where Hockney now lives and has his studio. This is the countryside where, like his agricultural labourer grandfather before him, Hockney had worked on a farm as a teenager, and where he now sketches incessantly.

The series illustrates a view of three trees painted from precisely the same spot during the winter and summer of 2007, and the spring and autumn of 2008.

There is absolutely constant change. Superficially, Bridlington and the country around haven’t altered much in fifty years. But when you are here, you can see how it varies continuously. The light will be different; the ground changes colour.

-David Hockney

Hockney paints each scene in vivid colours: spring dominated by the season’s abundant greens and yellows, while the winter version has the three bare trees silhouetted against a deep belt of blue with parallel bands of orange and green in the foreground.

Here the tree is introduced as a key motif of Hockney’s recent work, seeming to embody, as the RA’s guide puts it, ‘a vital life force, whether in full leaf in summer or as a bare structure in winter’. And there is Hockney’s other great theme in this recent work – nature’s transience. The Thaxendale series, along with others in the show, are all about nature’s cycles and the passage of time – the same process that engrossed Claude Monet when he devoted his later years to painting water lilies in his garden at Giverny over and over again.

I have painted these water lilies a great deal, modifying my viewpoint each time … The effect varies constantly, not only from one season to the next, but from one minute to the next … So many factors, undetectable to the uninitiated eye, transform the colouring and distort the planes of the water.

– Claude Monet

There have been some highly critical reviews of this exhibition, such as those by Andrew Graham-Dixon and Alastair Sook, and these have usually commented on the startling contrast between what Hockney is now doing and the work he created in Britain and America in his younger days. The next room, ‘Earlier Landscapes’, sets out to illustrate the extent to which landscape has always been present in Hockney’s work. Here is a selection of paintings spanning the years from 1956 (Fields, Eccleshill’ and ‘Bolton Junction’) to 1998 (the gigantic and glowing ‘A Bigger Grand Canyon’) by way of the humorous ‘Flight Into Italy – Swiss Landscape’ of 1962 and ‘Nichols Canyon’ from 1980.

The first two paintings were made when Hockney was a teenager studying at the Bradford School of Art. With their subdued colours and dull light they offer a marked contrast to the recent work.

‘Flight Into Italy – Swiss Landscape’ is Hockney’s at his most flippant, remembering when he went with some friends to Italy to look at paintings and architecture in a small van. Hockney was stuck in the back of the van (with the red coat, presumably), and so couldn’t see the mountains as they went through Switzerland. He painted them later from a geology textbook.

In ‘Nichols Canyon’ Hockney attempts to find a solution to the problem of portraying movement and the passage of time on the static two-dimensional surface of a canvas. In the painting he depicts how he saw – both in actuality and in the layers of memory built up through repeated journeys – the places he travelled through every day by car to his home at the head of Nichols Canyon. Hockney does not depict in any naturalistic way the canyon’s environmental features, nor does he illustrate the view from his home. Instead, he takes viewers on a journey through Nichols Canyon itself, visually recreating his daily drive from his home at the top of the canyon to his studio in Santa Monica Boulevard below it.

From this room, we ease into the Yorkshire landscapes beginning with the first ones that he completed between 1997 and 1999 after he had returned to Yorkshire to be near his close friend Jonathan Silver, who was terminally ill. Here are the by now familiar images ‘Road Through Sledmere’ (1997), ‘Double East Yorkshire’ (1998) and the magnificent ‘Garrowby Hill’ (1998), with its echoes of the California landscapes with its vivid colours and expressiveness of viewing the landscape from a moving car.

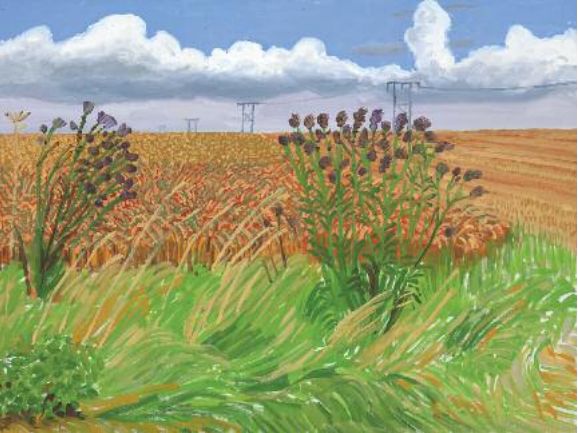

These first Yorkshire paintings were all painted in the studio from memory. By contrast, those in next room were all painted directly from observation in 2004 – 2005. Two of the walls are crammed with arrays of small or medium-sized paintings, some oils and some watercolours. One painting, ‘Wheat Field Off Woldgate’, shares an affinity with Van Gogh’s

‘Wheat Field, June 1888’. The point of view of each artist is similar: Vincent walked into the field to paint; Hockney, too, has set up his easel at the edge of the field, immersing us in the grasses and the wheat that stretches off into the distance where electricity pylons march. For Hockney, Van Gogh is simply a great draughtsman, his work manifesting the two qualities that Hockney values most and considers wholly entwined: rigorous observation and mastery of drawing.

There are more hints of Van Gogh later on in the exhibition, in paintings of hawthorn blossom and in the purple whorls of ‘Winter Timber’. The last room of the exhibition, which consists of a lavish display of 16 of Hockney’s sketchbooks and iPads, should not be overlooked. It reveals, as do Van Gogh’s drawings, how ‘everything begins with the sketchbooks’, in Hockney’s words, and how a supreme draughtsman can reveal the likeness of a man’s face in a few deft lines. As Brian Sewell put it in his otherwise scathing review of this exhibition, Hockney is ‘one of the best draughtsmen of the 20th century, wonderfully skilful, observant, subtle, sympathetic, spare, every touch of pencil, pen or crayon essential to the evocation of the subject’.

Another fine painting in this group is ‘Woldgate Tree’, a portrait of a solitary tree in early spring, just about to burst into bud. The tree is defined in just a few very fast brushstrokes, three slashes of yellow.

Every tree is different. Every single one. The branches, the forces in it; they are marvellously different. You are thrilled. This is the infinity of nature.

– Hockney

In these oils and watercolours, Hockney does indeed capture the infinity of nature: trees and puddles, clouds reflected in puddles, a series of poems in blues and greys.

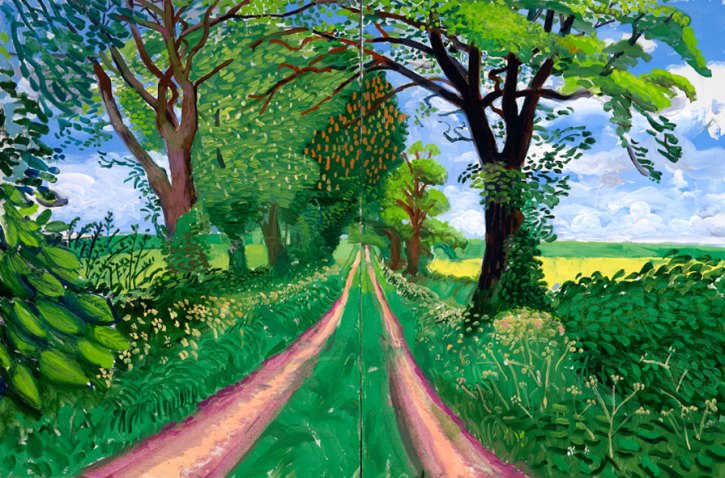

Then another room that demonstrates Hockney’s fascination with examining the same place at different times of the day and the year. This is ‘the tunnel’, a farm track near Kilham in the East Riding. In summer the dense growth of trees completely encloses the track, as shown in ‘Early July Tunnel, 2006’. Here is the same scene at two other seasons:

Woldgate Woods is another series of seven large paintings (each consisting of six canvases all made from the same viewpoint) that reflects Hockney’s admiration for Monet’s Water Lilies. Again there is close attention to to changing light and seasonal conditions (compare to the two versions below, painted a couple of weeks apart and at different times of day; another version, dated 7 & 8 November 2006, is suffused with a misty light, while ’26, 27 & 30 July 2006′ is a study in green – leaves in many shades, dappled light falling on a far glade). The height of the trees, the sense of space and the dazzling late autumn colours all heighten the intensity of being in nature. Hockney sets out to persuade us to open our eyes to our surroundings: ‘It doesn’t have to be Woldgate – your own garden will change as much’.

The next room is devoted entirely to paintings of hawthorn blossom. It is the strangest sight, and I wasn’t entirely sure about it (though amidst all the critical reviews that this exhibition has received, it was this room that critics tended to like the most). For the last three years, Hockney has prepared for what he calls ‘action week’, three or four days in late May or early June when the hawthorn blossom makes its fleeting appearance. Rising at dawn, Hockney has depicted the wild exuberance of the hawthorn in the early morning light. He says that this moment is ‘as if a thick white cream had been poured over everything’. I found Hockney’s preparatory charcoal drawings preferable.

Writing in The Guardian, Adrian Searle spoke of these landscapes having ‘an almost surreal and visionary delight’, culminating in

a painting so over the top – ‘May Blossom on the Roman Road’, from 2009 – that it looks as though giant caterpillars were climbing all over a kind of mad topiary, beneath a roaring Van Goghish sky. I wish more works could be as crazy as this: Hockney captures and amplifies something of the astonishment of hawthorns in bloom. I kept thinking of dying Dennis Potter describing in that 1994 interview with Melvyn Bragg how “nowness” had become so vivid: “Instead of saying, ‘Oh, that’s nice blossom’ … I see it is the whitest, frothiest, blossomest blossom.

It is a very weird painting.

On we go to a room entitled ‘Trees and Totems’, comprising a group of paintings of trees and cut timber in winter. Here, Hockney juxtaposes the freshly-cut logs against the verticality of the purple ‘totem’ suggested by a hewn trunk and the myriad blue trees that remain upstanding, protectively surrounding the dead wood. It is highly expressionistic, with vivid patterning (the tractor tracks on the purple trail in the foreground, the leaves and bracken alongside the logs seeming to evoke a William Morris design, and the marks on the bark of the violet stump). Your eye is drawn along the line of the logs and the curve of the pink track on the left towards the Van Gogh whorl in the distant trees. This is Alastair Sook in The Telegraph:

Another series, Winter Timber and Totems, introduces a touch of foreboding and forlorn melancholy. We are in the woods. Using an extreme Fauvist palette, Hockney paints tree stumps and felled logs. The culmination of the sequence is the 15-canvas oil painting ‘Winter Timber ‘ (2009). An imposing magenta stump dominates the foreground. Next to it, piles of orange logs stripped of their bark lie beside a road that leads off into the distance. The track is flanked by slender blue trees, some of which start to bend and curl into a disconcerting vortex as they approach the horizon. Thanks to the preternatural colours, the scene feels uncanny, suffused with the intensity of a vision. It doesn’t take long to read the stump and logs as reminders of mortality, or to understand that Hockney has transformed a humdrum wintry scene into a gateway to the afterlife. … Paintings such as ‘Winter Timber’ go beyond mere topographical record, and remind us of the power of Hockney in his prime.

After the ‘Arrival of Spring’ gallery, there are two decidedly unimpressive rooms. One consists of paintings inspired by Claude Lorrain’s ‘The Sermon on the Mount’ (1656) which Hockney encountered in New York in 2009. Having acquired a digital copy of the painting, he digitally ‘cleaned’ the surface which had darkened due to exposure to fire two centuries ago. Brian Sewell was scathing about Hockney’s resultant studies in his exhibition review. They didn’t appeal to me.

A final gallery of paintings gathers some of Hockney’s most recent work. The room is dominated by very large prints of iPad paintings of the Yosemite Valley in California. All that can be said about these is that blowing them up to this size exposes the limitations of iPad works which have charm and delicacy at their original size. However, the three recent oil paintings of Woldgate in this final gallery, with their close focus on the wild flowers and grasses growing beneath trees and the delicate flowers of Queen Anne’s Lace are a delight.

Queen Anne’s Lace (or Cow Parsley as it’s generally known up north) is so ubiquitous along English roadsides and hedgerows that it tends to fade into invisibility. But Hockney has latched onto it in these recent paintings – and in the 18-screen high definition films that he has developed as another means of depicting the landscape which are shown in the penultimate room of the exhibition.

In the past, Hockney has criticised photography, saying that it is ‘all right, if you don’t mind looking at the world from the point of view of a paralysed Cyclops’. What these films (stunning in the high-definition clarity and in their widescreen opening to peripheral vision) are about is his attempt to overcome the discrepancy between how we see the three-dimensional world in space, volume and time, and how to translate that vision into a two-dimensional representation. He tried this before with his photo collages in the 1980s ( a few of which are on display here in the ‘Earlier Landscapes’ room).

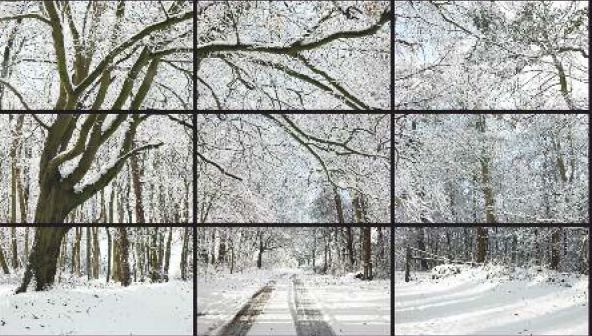

In 2007, Hockney began experimenting with a set of nine synchronised, high-definition, video cameras attached to a rig on his Jeep. Hockney and his assistants drive slowly along the road to ‘The Tunnel’, for instance, filming first one side of the road, and then the other side, before joining them together. ‘A single camera isn’t very good at showing landscape,’ he claims, ‘but the nine cameras are’.

We see space through time. When you’re seeing the nine-camera videos of Woldgate, it’s a different time in the top right-hand corner from what it is in the left-top corner. Just as it is in real life for you.

– Hockney

The films run for about 20 minutes or so, and are both beautiful and hypnotic. This is not simply a widescreen movie: by aiming each of the nine cameras in a slightly different direction, Hockney’s team have got close to how we experience walking through a landscape with our own eyes.

As a finale, there are scenes filmed in Hockney’s Bridlington warehouse studio with a pianist and ballet dancers, nods to Degas, Matisse and maybe Van Gogh (yellow chairs) and, at the end Hockney raising a red mug. At one point we see a poster with the message, ‘DEATH waits for you when you do not smoke’ (incontrovertible for sure, and an expression of the combative position on smoking that Hockney has repeatedly taken).

This is an enormous exhibition, filling ten rooms, including the vast Gallery III devoted to ‘The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire, in 2011’. It comprises vast oil paintings, the 52 works in ‘The Arrival of Spring’ (51 of which are iPad drawings: the 52nd is a 15 metre oil painting), a wall of 18 screens showing footage from 18 cameras, a wall of watercolours, a room filled with sketchbooks (each displayed with a monitor above it, on which the pages open in a slideshow), another displaying 12 ft high iPad drawings of Yosemite, a scattering of charcoal drawings and a number of earlier landscapes. It has been hugely popular with the public, yet almost all the reviews by art critics were hostile to a greater or lesser extent.

It is undoubtedly true that, having decided to fill the Royal Academy with work completed almost entirely in the last six years, Hockney has run the risk of quantity exceeding quality. There certainly could have been some pruning. I could have done without the Yosemite iPads and the Lorrain homage. But it is the sheer quantity of images (sometimes stacked two or three deep on the walls) that succeeds in immersing the viewer in the exuberance and ever-changing character of the natural landscape. It is this, I think, that makes the show so popular. Hockney knows how to convey – in oils, watercolours or scratches and smears on an iPad screen – a misty November morning, the sharp sunlight of an early May morning, or bars of autumn sunlight slanting through the trees in Woldgate Wood. He leads us to see the things that we stop seeing because they are so familiar – roadside nettles, Queen Anne’s lace, dock leaves and wild flowers, the fantastical shapes of hawthorn blossom, and trees in their endlessly varied structure and foliage.

He experiments endlessly with new technologies, but not for its own sake. The 18-screen films, like the very large scale of his new paintings, is about trying to capture the experience of seeing in three dimensions, making us crane our necks, walk about, glance all over the place. These works – indeed the whole exhibition – envelop the viewer, as if the landscape isn’t simply out there, like a flat surface or a window, but all around us.

As for the iPad drawings – the speed with which Hockney can create them has allowed him to capture changing light effects through the day or the seasons. And that is the real theme of this exhibition – the representation of time itself, moving through the day, moving through the year, moving from shadow into bright sunlight.

See also

- Royal Academy: about the exhibition (with image gallery)

- David Hockney RA: A Bigger Picture Education Guide (pdf)

- Review: Adrian Searle (The Guardian)

- Review: Andrew Graham-Dixon (The Telegraph)

- Review and video: Alastair Sook (Telegraph)

- Review: Laura Cumming (The Observer)

- Review: Brian Sewell (Evening Standard)

- Hockney Trail: unoffical trail through the Yorkshire Wolds and locations the artist used in his paintings

- David Hockney: official website

- David Hockney’s new exhibition at Salt’s Mill

Fantastic I love it!

Thanks for this wonderful room by room tour of the exhibit.

A fine review.

Very perceptive and balanced review – you have to admire Hockney for his sheer joie de vivre even if you don’t like all the work.

I don’t think I like Hockney. He’s a ridiculous chain smoker who rants, and rants, and rants, about the right – effectively – to impose his noxious habit on other people by protesting against the recent ban. Said, in fact, he disagreed with it so much he was considering living elsewhere – utterly pathetic.

His rants against photography are also tiresome. Its a different medium with different aesthetics, goals and advantages – and that is all.

I don’t agree with him on smoking. I see what he’s getting at about photography, but agree with you that it is a medium with its own aesthetics and qualities. But I love Hockney for the sheer joy he has given in the last 5 decades.

Thank you for that wonderful description. Tickets for the exhibition are sold out so it is great to have some idea of what it was like.

Thank you for posting! Love Hockney and his juxtaposition of unusual colors.